Ukraine's "Orange Revolution" (2004-05)

Regime Change and Colour Revolutions Part 5

Previous Entry - Georgia’s “Rose Revolution” (2003)

By this point in the series, you should be able to detect a pattern present in each and every one of the historical examples of regime change that we have covered thus far. The pattern is comprised of the following elements:

a post-communist state that has transitioned towards multiparty democracy

a government not aligned with US foreign policy objectives, and thus targeted for regime change

economic hardship as a result of the transition from a command economy to a market-oriented one, compounded by the challenges of globalism and corruption

popular dissatisfaction with the government with sharp, polarized divisions among citizens

International (read: western or western-controlled) organizations attacking the government as “autocratic” or “dictatorial”, and “in violation of the rule of law”

destabilization of the regime via the flooding of the country with western-backed, trained, and financed NGOs who work hand-in-glove with local opposition, the US State Department, the CIA, etc.

A “big tent” coalition of opposition parties put together by US officials as “broker” to take on the government in the next election

an upcoming election that the political opposition declares “rigged”

“independent media” (western funded) blasting the message of fixed election results

massive protests well-organized in advance and intensively covered by western media to put international pressure on the regime to step aside and allow a new vote or recount of vote that has just taken place

a defection of elements of state security (whether it be intel, secret police, military) to the opposition side, generally through bribery/promises of continuation/expansion of existing role under new regime/amnesty, or a combination thereof, presenting a fait accompli to the present regime, forcing them to step aside

Every single element listed above was present in 2000 in Yugoslavia, and in 2003 in Georgia, with many also visible during the test run in Slovakia in 1998. As you will see, all of these elements will be on full display in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution as well. The only differences between each of these colour revolutions are the fine details of the countries being investigated.

Unlike the last two entries where I provided a deep-dive into the histories of Yugoslavia and Georgia, I am not going to do the same regarding Ukraine. Ukraine is now in the news daily, and my readers are already very well-informed on the subject, especially in comparison to the previous two countries that we have covered in this series. On top of this, you already know what to expect from this entry (see: list above).

Much of what will be discussed in this essay will help fill in some of the gaps that you might have in your knowledge of Ukraine, and it will also assist you in better understanding what has happened since then. At the same time, I am going to ask you to try and forget everything that has happened there since the Russian invasion last year (even better if you can try to forget all the way back to pre-Maidan 2014).

What you will witness here is another example of the USA opportunistically exploiting political division in a country that they have targeted for regime change. As seen already in this series, these colour revolutions did not occur in a vacuum. Popular dissatisfaction with the ruling government made the job of regime change easy for the Americans and their allies. The idea that these regime changes did not reflect much of the popular sentiment in Yugoslavia, Georgia, and Ukraine is simply nonsense.

Encroachment on “Russia’s Turf”

The Soviets voluntarily left the Warsaw Pact countries in the early 1990s, effectively ceding them to the West, with the proviso that they wouldn’t join NATO (a deal quickly violated by the opposing side). 1998 Slovakia was not in Russia’s sphere of influence, and therefore wasn’t a big concern to Russia, especially considering the horrendous state of affairs in their own country at the time.

The overthrow of Slobodan Milosevic in 2000 did not bother Russia anywhere near as much as the occupation of Kosovo in 1999 (as symbolized by Premier Primakov turning his plane around in mid-air while on his way to Washington, DC, upon learning that NATO was about to bomb Yugoslavia). The occupation of Kosovo by NATO was very significant (a direct line can be drawn to the annexation of Crimea in 2014). The removal of a discredited and spent force in the form of Slobodan Milosevic was perceived as an inevitability. Besides, the incoming government in Yugoslavia contained quite a lot of pro-Russian figures anyway.

Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution was a completely different matter altogether. Georgia, an ex-Soviet republic, was seen as belonging to Russia’s “near abroad”, i.e. its sphere of influence. It was a member of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), an organization promoting political, economic, and military cooperation among all the former Soviet republics, with the exception of the three Baltic ones. Even though the Shevardnadze-led government in Tbilisi wasn’t exactly a Russian client regime, its overthrow and replacement with a US-backed one sounded the alarms in Moscow as Georgia was in Russia’s backyard. This, to Moscow, was an intolerable breach of Russia’s security interests, and a violation of the decent-to-good relations that prevailed between the countries in the early years of both Putin’s and George W. Bush’s respective presidencies.

Besides the “violation” of Russia’s sphere of influence, Moscow feared that Georgia would be used to transit oil and gas from Central Asia to Europe, a market dominated by Russia, via the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline (BTC), one that completely avoided Russian territory altogether. Furthermore, Russia also feared that the CIA and MI6 would use Georgia as a covert base of operations to destabilize Russia’s Caucasian region, via the infiltration of Mujahideen fighters into Chechnya and Dagestan. Tony Blair confirmed the validity of these fears in 2008:

McCain said this was why he was developing the concept of a "league of democracies" to join like-minded nations together in common cause based on shared values. He asked Blair his views on Putin. "The problem with managing Putin and Russia," said Blair, "is that we have to deal with them when it comes to

Iran." The rest of the strategy, he said, should be to make Russia a "little desperate" with our activities in areas bordering on what Russia considers its sphere of interest and along its actual borders. Russia had to be shown firmness and sown with seeds of confusion.

The capture of Georgia and its reorientation towards the West by the USA was viewed by Russia as not just a slap in the face, but also a threat to its national security. The goodwill that was established between these two nuclear powers was beginning to evaporate as the USA began to chip away at Russia’s near abroad.

Some of you might raise an objection here, asking about the right of peoples to national sovereignty and decision-making. This is a fair point to raise, but everyone must realize that not all states are created equal, and some live in harsh neighbourhoods like the Caucasus. A state has the right to determine its own path and policies, but it must be done in recognition of the reaction that it would generate from its neighbours, and from distant great powers that have an interest in the region as well. That is the world that we live in.

The world that we lived in back in 2003 wasn’t as clear to us as it is today, particularly when it comes to appeals to “freedom” and “democracy” that emanated from western governments, think tanks, and media. As the occupation of Iraq began to bog down, US foreign policy planners and intelligence agents turned their eyes towards a big prize: Ukraine.

The Geopolitical Significance of Ukraine

As promised, we are not going to delve too deeply into the history of Ukraine as this essay would quickly become a book in length. Our interest here is in the independent state known as ‘Ukraine’, a country that was a Soviet republic in the USSR.

The first Russian state was the Kievan Rus, a medieval polity centred around Kiev. Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine all claim ancestry from it. The Mongol invasion of the 13th century dealt it a severe blow, reducing its size and strength as many of its component parts began to go their own way. The presence of Kievan Rus on what is today Ukrainian soil forms a large part of the historical argument held by Russian nationalists and royalists who claim that Ukraine is Russian soil and that (most) ethnic Ukrainians are simply Russians, or “malorusi” (Little Russians), a term used in both the Medieval and Romanov eras to describe large parts of today’s Ukraine.

To many Russians, the Ukrainian identity is either not a real one, or is classified as a sub-ethnicity falling under the larger Russian one (I am not going to delve into the ethnic aspects here for the sake of brevity). They are both Eastern Slavs and are Orthodox Christians (with the exception of the Byzantine Catholics in Ukraine’s west), and who speak the same language, for the most part.1 Combine this view with the historical argument above, and it instantly becomes clear why Russia (and Belarus as well) are different in the minds of Russia and Russians than Georgia, Armenia, or Uzbekistan, for that matter.

On the other hand, Ukrainians have long insisted that their identity has a longer history than it is accorded, and a much more independent one than Russians will allow for. They will also argue that much of Ukraine underwent a process of ‘Russification’ under the Romanovs, which led to the suppressing Ukrainian identity and national consciousness, and that this policy continued under the Soviets, with the Holodomor being the culmination of this centuries-long process.

The end of the Soviet Union saw Ukraine declare independence after 92.3% of all voters voted for this choice in a referendum held on December 1, 1991. More than 84% of all eligible voters cast a vote, giving this referendum wide legitimacy. For the first time in centuries, Ukraine was formally independent of Russia, with global recognition of its status as such. It quickly became an associate member of the CIS for various reasons, including the desire to not upset Russia.

Although officially independent, Ukraine was still heavily influenced by its larger neighbour. Ukraine’s economy was totally integrated with the rest of the Soviet successor states, and its military and intelligence services ridden with individuals for whom “Ukrainian independence” was not to be taken seriously. Much of the population of the country was outright ethnic Russian, or partial to Russia (more people spoke Russian than Ukrainian in Ukraine at the time), with Ukrainian nationalists struggling to find their footing politically outside of Galicia.

At the same time, its officially-recognized status as an independent state gave the USA its first opening in its efforts to surround and neutralize Russia. If the Americans could wrench Ukraine out of Moscow’s orbit, Russia would be significantly weakened. Allow Jimmy Carter’s National Security Advisor (and ethnic Pole) Zbigniew Brzezinski to explain:

Ukraine, a new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard, is a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps to transform Russia. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire. Russia without Ukraine can still strive for imperial status, but it would then become a predominantly Asian imperial state, more likely to be drawn into debilitating conflicts with aroused Central Asians, who would then be resentful of the loss of their recent independence and would be supported by their fellow Islamic states to the south. China would also be likely to oppose any restoration of Russian domination over Central Asia, given its increasing interest in the newly independent states there. However, if Moscow regains control over Ukraine, with its 52 million people and major resources as well as its access to the Black Sea, Russia automatically again regains the wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state, spanning Europe and Asia. Ukraine's loss of independence would have immediate consequences for Central Europe, transforming Poland into the geopolitical pivot on the eastern frontier of a united Europe.2

Without Ukraine, Russia becomes an Asian power, and therefore regional instead of global. Therefor, Ukraine is for Russia an existential matter.

Brzezinski wrote the words above in 1998, the year that Russia defaulted on its debt and went broke. When added to its political and social collapse, wolves like Zbig and Strobe Talbott saw an opportunity to move in for the kill.3

The loss of Ukraine would mean the loss of the Russian naval port at Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula, which would effectively cede the Black Sea to the West. It would also put into jeopardy the oil and gas pipelines that traversed the country that sent these resources from Russia to the energy-starved European market (remember that this is 2004-05, when China’s appetite for oil and gas was not as large as it is now, nor was the infrastructure in place to send it to them anyway).

Samuel P. Huntington classified Ukraine as a ‘cleft state’:

Cleft countries that territorially bestride the fault lines between civilizations face particular problems maintaining their unity.4

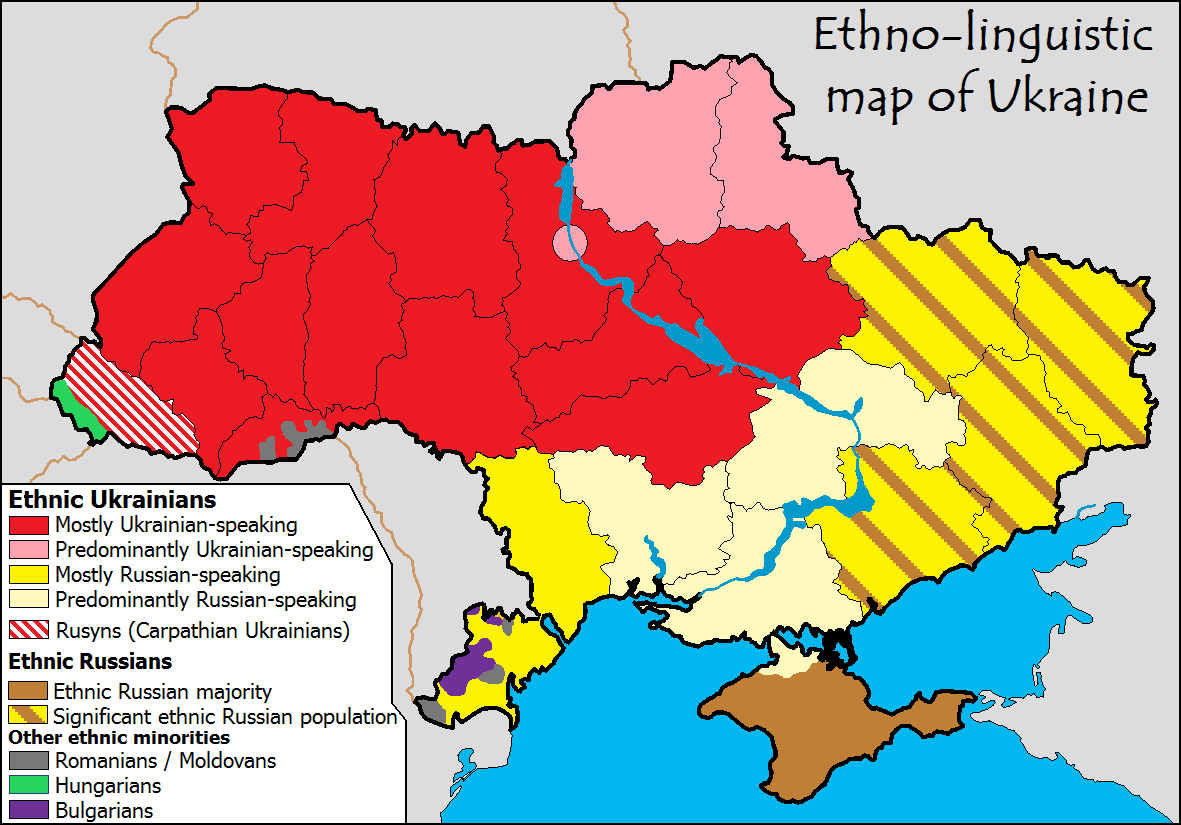

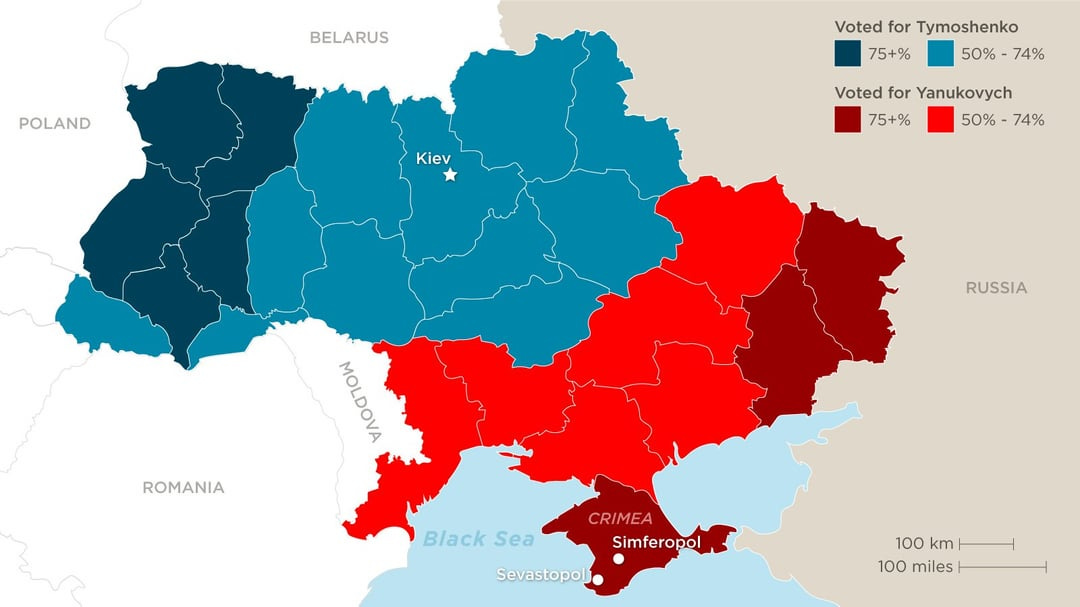

The divisive effect of civilizational fault lines has been most notable in those cleft countries held together during the Cold War by authoritarian communist regimes legitimated by Marxist-Leninist ideology. With the collapse of communism, culture replaced ideology as the magnet of attraction and repulsion, and Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union came apart and divided into new entities grouped along civilizational lines: Baltic (Protestant and Catholic), Orthodox, and Muslim republics in the former Soviet Union; Catholic Slovenia and Croatia; partially Muslim Bosnia-Herzegovina; and Orthodox Serbia-Montenegro and Macedonia in the former Yugoslavia. Where these successor entities still encompassed multicivilizational groups, second-stage divisions manifested themselves. Bosnia-Herzegovina was divided by war into Serbian, Muslim, and Croatian sections, and Serbs and Croats fought each other in Croatia. The sustained peaceful position of Albanian Muslim Kosovo within Slavic Orthodox Serbia is highly uncertain, and tensions rose between the Albanian Muslim minority and the Slavic Orthodox majority in Macedonia. Many former Soviet republics also bestride civilizational fault lines, in part because the Soviet government shaped boundaries so as to create divided republics, Russian Crimea going to Ukraine, Armenian Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan. Russia has several, relatively small, Muslim minorities, most notably in the North Caucasus and the Volga region. Estonia, Latvia, and Kazakhstan have substantial Russian minorities, also produced in considerable measure by Soviet policy. Ukraine is divided between the Uniate nationalist Ukrainian-speaking west and the Orthodox Russian-speaking east.

In a cleft country major groups from two or more civilizations say, in effect, “We are different peoples and belong in different places.”5

Nowhere is this divide more visible than in the following two maps. The first is a linguistic map of Ukraine, the second is the results from the 2010 presidential election that pitted Viktor Yanukovych against Yuliya Tymoshenko:

Immediately after declaring independence, Ukraine was being pulled in two different directions: one to the west, and the other to Russia. For the first two decades of its existence as an independent state, the latter was politically dominant.

One more excerpt from Huntington (recall that this was written in 1996) that is very significant to the present conflict happening in Ukraine now:

Russia vigorously opposed any NATO expansion, with those Russians who were presumably more liberal and pro-Western arguing that expansion would greatly strengthen nationalist and anti-Western political forces in Russia. NATO expansion limited to countries historically part of Western Christendom, however, also guarantees to Russia that it would exclude Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Belarus, and Ukraine as long as Ukraine remained united. NATO expansion limited to Western states would also underline Russia’s role as the core state of a separate, Orthodox civilization, and hence a country which should be responsible for order within and along the boundaries of Orthodoxy.6

Brzezinski and Huntington together make the case for Ukraine’s geopolitical importance a very simple one to understand.

From Independence to the Orange Revolution

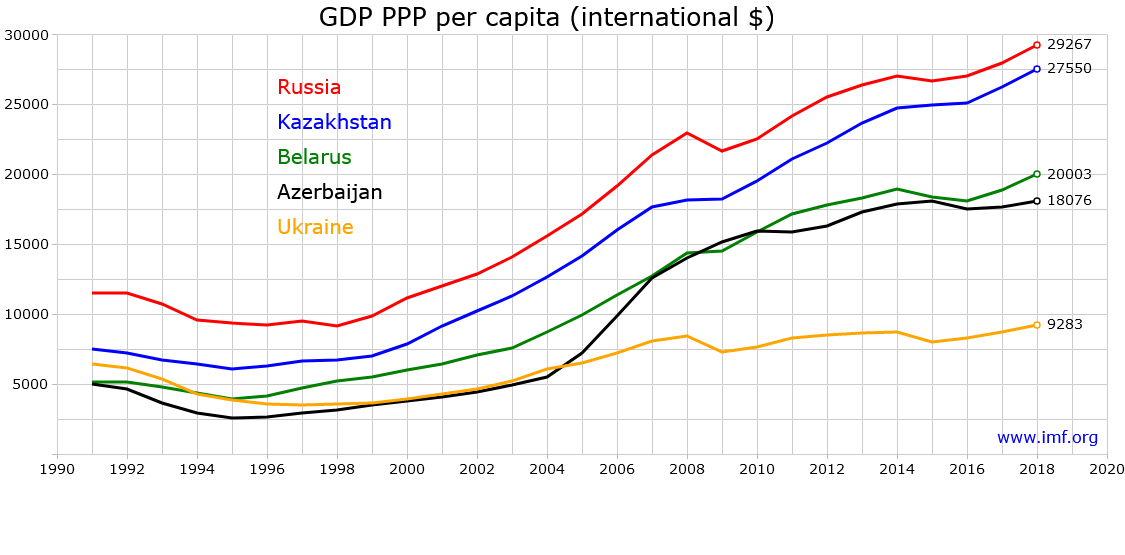

Ukraine should be a rich country today and Ukrainians should be enjoying a rising standard of living akin to their Polish neighbours. The country has the world’s largest reserves of commercial-grade iron one (30 billion tonnes, roughly 20% of the global total), Europe’s second largest known natural gas reserves, and a massive defense industry inherited from the Soviet era. 70% of the country is covered by agricultural land, making Ukraine the world’s fifth biggest exporter of wheat and its biggest exporter of seed oils. Chemicals, mechanical products, and coal mining, plus a robust and highly-skilled IT sector round out what should be a great economic story.

The reality is that Ukraine has been an economic basket case throughout its history of independence. This has caused it to be the economic “sick man” of post-communist Europe, best illustrated by the following graphs and charts:

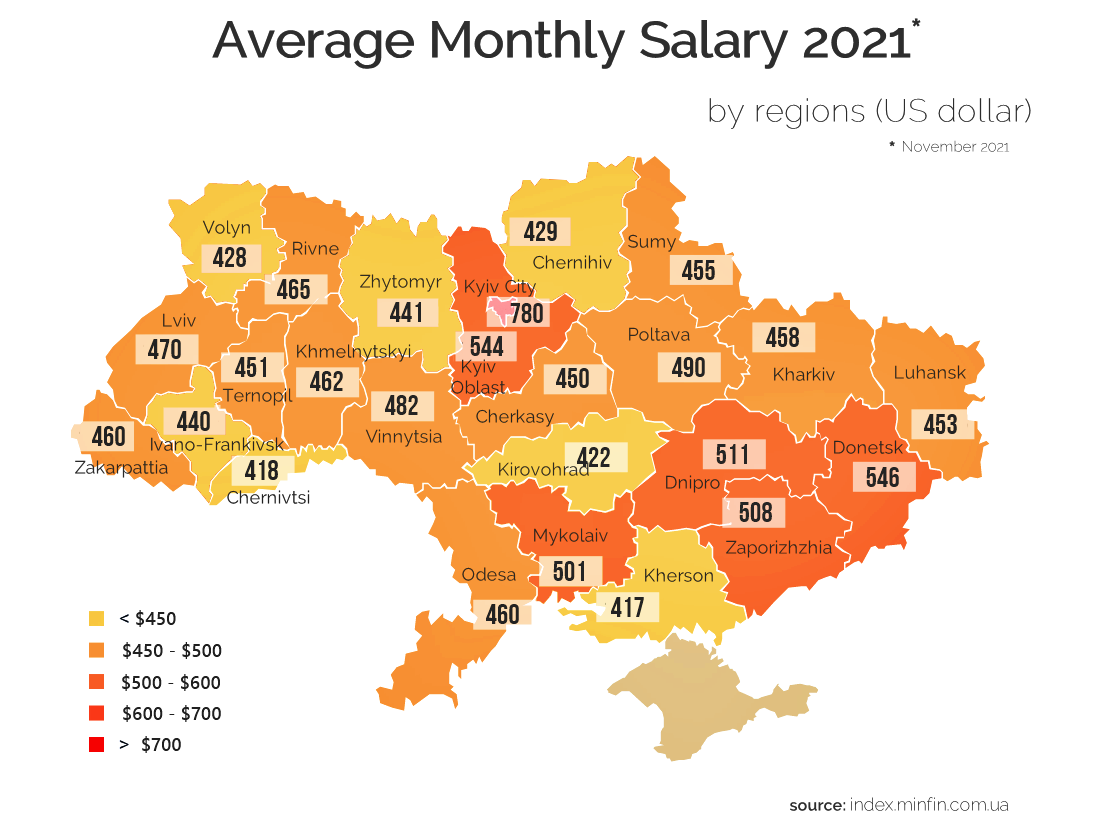

And one last one to see how the misery is spread across the country:

The story of Ukraine from independence to the Orange Revolution is one of unfulfilled economic potential, paralyzed political systems, and the rise of non-ideological, self-interested regional oligarchies in competition with each other over power. The only thing missing during this period was ethnic conflict…something that would erupt later on in the future.