Serbia's "Bulldozer Revolution" (2000)

Regime Change and Colour Revolutions Part 3

Previous Entry - Security Vacuum and Streamlining Democracy

Note: this is a very expansive topic, one that I could write a book about blindfolded. As I am not writing a book but an article, there will be quite a bit that I will be forced to gloss over for the sake of brevity (‘brevity’ here is relative, as this is a very, very long essay due to its many complexities). Forgive me for this and use the comments section to nitpick, where I will more than happily respond to you.

Second Note: I will strain for objectivity on this subject, especially due to my ethnic background. Serbs who have been reading me for some time now are quite numerous here, and have expressed appreciation in the past for how I have tried my best to strike a fair balance when discussing them.

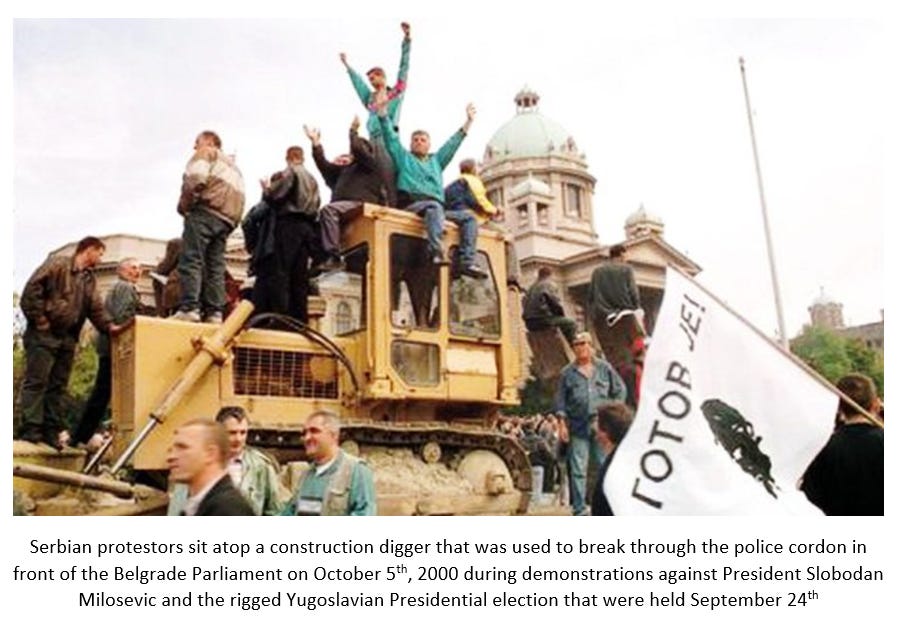

On October 5, 2000, Belgrade, the capital of rump Yugoslavia1, was being rocked by a wave of massive protests stemming from widely-believed accusations that the presidential elections held almost two weeks prior on September 24th were fixed so that opposition candidate Vojislav Kostunica would be forced into a second round runoff against sitting President Slobodan Milosevic. The official count released by the state electoral commission had Kostunica win just under 50% of the votes in the first round (50%+1 vote would have meant that he would have won the Presidency outright, without need for a runoff), meaning that he would have to face off against Milosevic head-to-head in the second round.

Serbians (and other citizens of Yugoslavia) were by that point very used to Milosevic’s tricks, and wanted no more. Unlike previous demonstrations, the police that day did not viciously attack the protesters. Sensing a change in the air, Ljubisav Đokić took his seat in his digger (misreported as a bulldozer) and broke through the police cordon. This symbolic act of defiance came to define what became known as the “Bulldozer Revolution”, and also to represent the moment when Milosevic finally capitulated to the swelling opposition to his rule.

Milosevic, a wily tactician, was finally bested. He had in the past managed to free himself from being cornered time and time again, but this time was different.

From Reformer to Pariah to “Partner in Peace”, and Back to Pariah

If ever there was a real life tragic Shakespearean character, it would have to be Slobodan Milosevic. Strap in, you’re in a wild (and very long) ride.

Slobodan was born in the eastern Serbian city of Pozarevac shortly after the German occupation of Yugoslavia in WW2. His father, Svetozar, was a Serbian theologian who taught Russian and Serbian, and was descended from the largest Serbian tribe in Montenegro, the Vasojevici (another famous member of that tribe is actress Milla Jovovic). Slobodan’s mother, Stanislava, was also a Montenegrin Serb. A schoolteacher, she was a fiery communist, which caused friction with her husband. They divorced shortly after the end of the war.

Svetozar returned to his village in Montenegro. In 1962, he put a pistol to his own head and pulled the trigger, killing himself. He could not live with the fact that a student committed suicide after receiving a poor grade from him. Stanislava ended her own life in 1974, just like her brother, the famous Yugoslav General Milisav Koljenšić.2

Slobo joined the League of Communists (aka Communist Party of Yugoslavia), and befriended Ivan Stamoblic, a party member whose uncle was a “national hero” due to his wartime record, and now a powerful communist politician as well. Attaching himself to Ivan, he quickly rose through the party ranks, and was appointed head of Beobanka, one of the country’s largest banks, in 1978. This important position had him spend time in the West, especially New York City, where he got to meet some of the most important and powerful people in the world while brushing up on his English-speaking skills. Slobo used to like to tell the story about how he was once in a meeting with Henry Kissinger and saw Henry's face go white when a secretary interrupted the meeting to tell him that David Rockefeller wanted to speak to him on the phone immediately.3

To add to the Shakespearian theme, Slobo found a wife in the form of Mirjana Markovic. Mirjana’s mother, Vera Miletic, was the party secretary for Belgrade, charged with organizing members living underground in the capital during German occupation. She fell into the hands of the police in October of 1943, and was repeatedly tortured for weeks on end. She gave up the names and details of up to 260 party members (many of whom were then captured and executed), dealing a significant blow to the party. Vera would later be executed by firing squad at Banjica camp.4

Mirjana was dealt a massive psychological complex from birth as a result of this. Her mother was viewed at best as weak, and at worst, a traitor. She compensated by becoming more ideologically communist than practically anyone else from her generation. Her steely mental discipline also gave her the tools to have an outsized influence on her husband’s political career.

Although a loyal communist party member, Slobo (unlike his wife) was never an ideological communist. He was more concerned with amassing power, something he had been doing as he rode his best friend Ivan Stamoblic’s coattails up the ladder of the party, becoming President of the Serbian Central Committee of the League of Communists in 1986. This powerful position gave him the ability to place his own loyalists within the party to build out his own centre of power. He then waited for the opportune time to attack.

The Stab in the Back

In April of 1987, Slobo went to the Serbian province of Kosovo to investigate a flare up in ethnic animosity between local Serbs and Albanians (more on this in a bit). Rather than hold to the overarching Yugoslav communist “Bratstvo i Jedinstvo” (Brotherhood and Unity) credo, Slobo picked a side, throwing his lot in with the local Serbs over the Albanians. "No one should dare to beat you again!", Slobo proclaimed, in front of television cameras that would later that night beam the images throughout Yugoslavia, changing the country forever.

Picking a side in an ethnic dispute was a no-no for communists. Through this violation of communist orthodoxy, Slobo had opened up the Pandora’s Box of nationalism, one that required an authoritarian and dictatorial police state to suppress. Ivan Stambolic, his patron and best friend, later went on to say that this was the day that he saw “the end of Yugoslavia”.5

Although violating communist orthodoxy, Slobo managed to outmaneuver his opponents in the Serbian party, sidelining them through procedural methods with the support of the loyalists that he installed in key party roles. First came Stambolic loyalist and Belgrade chief Dragisa Pavlovic. He was expelled from the party after criticizing its Kosovo policy. Stambolic, then isolated, was fired thanks to trumped up charges of conspiring to forestall the vote to remove Pavlovic. By February of 1988, Slobo had become the President of Serbia, and all he had to do was play the nationalist card and stab his best friend in the back at the same time.

Consolidating Power

Upon taking supreme power in the Socialist Republic of Serbia, the first thing that Slobo did was set up a commission of neo-liberal economists to institute free market reforms backed by the IMF:

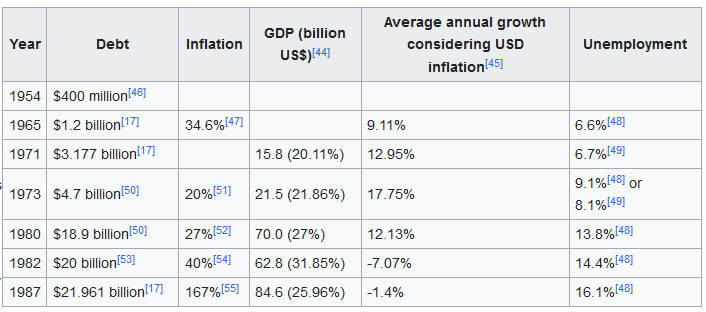

Woodward and others have claimed that with the “special relationship” coming to an end after the Cold War, the West no longer had an interest in “Yugoslav territorial integrity and independence”. In reality, Western powers continued to insist not only on the maintenance of Yugoslav unity, but on the strengthening of the central apparatus, particularly the Federal Executive Council (FEC), which selected the prime minister, as Woodward, ironically, elsewhere demonstrates forcefully. This was due to the demands of the IMF and World Bank (organisations ultimately controlled by Washington) for greater central authority to force repayment of the $20 billion foreign debt, to carry out a “free market” transformation and privatisation of the economy, to overcome republican barriers to an unrestricted Yugoslav-wide market for Western investments and goods, and to remove the republican veto on federal economic decisions dictated by the IMF. This stubborn insistence on centralisation eventually led to the Yugoslav break-up for the opposite reason — the non-Serb republics could no longer bear the increasing weight of the central regime.

The target of this IMF campaign was Tito’s 1974 constitution, which had in effect

set up a confederation, lacking any real central economic control. Yugoslavia’s six

republics and two “provinces” gained major economic powers compared to the centre. A “republican veto” existed over any federal decision, including macro-economic matters.6

Slobo, thanks to his time spent in banking in New York City, was seen as a “man we could do business with”, by such luminaries as Kissinger protege Lawrence Eagleburger, the Deputy Secretary of State under George Bush the Elder.7 Slobo was being positioned as "Yugoslavia's Gorbachev" i.e. a reformer of the system, both economic and political. Yugoslavia lived high on the hog during the 1970s, thanks to western loans that were now being called in. With the backing of western political and financial interests, Milosevic was given the green light to centralize power in Yugoslavia so as to be able to pay back the loans via "economic shock therapy".8 Even better, his contacts like Eagleburger were already enmeshed in business dealings in Yugoslavia at the time.9

In 1974, Yugoslavia adopted a new constitution that saw a strengthening of the individual republics at the expense of the central government in Belgrade. At the federal level, each of the six republics received one vote. At the same time, Serbia’s two autonomous regions, Vojvodina and Kosovo, also received one vote each. This constitution was brought in to curb Serbia’s increasing dominance of Communist Yugoslavia, something that was a central feature of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia that existed prior to WW2. Naturally, Serbs were not enthused about being cut down to size.

Milosevic quickly removed the governments of Vojvodina, Montenegro, and Kosovo in quick succession through what were called “anti-bureaucratic revolutions”, via the reputation he earned by tapping into Serbian nationalist sentiment during his infamous 1987 visit to Kosovo. By 1989, Milosevic controlled four of the eight votes at the federal level. All he needed was one more and he could rewrite the Yugoslav constitution to reduce the autonomy of the individual republics and centralize power under him via the League of Communists. In short, he was on the verge of becoming a second Tito (Yugoslavia’s communist dictator from 1945 to 1980).

The Centre Could Not Hold

These moves did not take place in a vacuum.

By 1989, the Yugoslav economy was cratering due to hyperinflation10, unemployment, mismanagement, corruption, and high levels of external debt. Yugoslavia’s unique brand of socialism, “workers’ self-management”, was falling apart, much like what was happening in the Soviet Union.

This spurred on the economic reforms that Milosevic was claiming to support.

At the same time, the Berlin Wall was falling, with the entire Cold War system rapidly dissolving. Democracy was in the air, and that included Yugoslavia as well.

The Socialist Republics of Slovenia and Croatia grew increasingly worried by Slobo’s centralizing moves as they saw their own autonomy being threatened. Both republics’ communist parties withdrew from the federal body in protest at Serbia’s drive for centralization. Slovenia and Croatia, both much more wealthy and economically developed than the rest of Yugoslavia, were seeking quite the opposite of what Slobo wanted. What they sought was an even looser federation, to the point of a confederation. To put it simply: the centre could not hold.

Slovenia and Croatia, both overwhelmingly Catholic and with the sense of belonging to the West historically and culturally, seized the moment by ending the communist monopoly on power in their republics via the adoption of multiparty democracy and elections. In Croatia, nationalists led by the HDZ party won big. Unlike Slovenia, Croatia had a sizable Serbian minority (12% as per 1991 census), one with nasty memories of being oppressed and slaughtered the last time there was an independent Croatian state.

Seeing that Yugoslavia was coming apart at the seams, Slobo once again played the nationalist card, informing Croatia that it would not be allowed to leave Yugoslavia in one piece due to its sizable Serbian minority. He quickly sent agents and arms to Serb communities in Croatia, where they set up roadblocks to prevent Croatian police forces from entering. At the same time, Croatia’s special police forces were disarmed by federal forces. Post-communist Slovenia and Croatia were moving towards independence, but unlike Slovenia, Croatia did not have control over the entirety of its territory.