Regime Change and Colour Revolutions Part 2: Security Vacuum and Streamlining Democracy

The Fall of the Berlin Wall, Rise of Multiparty Democracy in Post-Communist Europe, NATO Expansion, George Soros' Has a Vision, Pax Americana, Slovakia as Test Run

Previous Entry - Mrs. Humanitarian Intervention Goes to Budapest

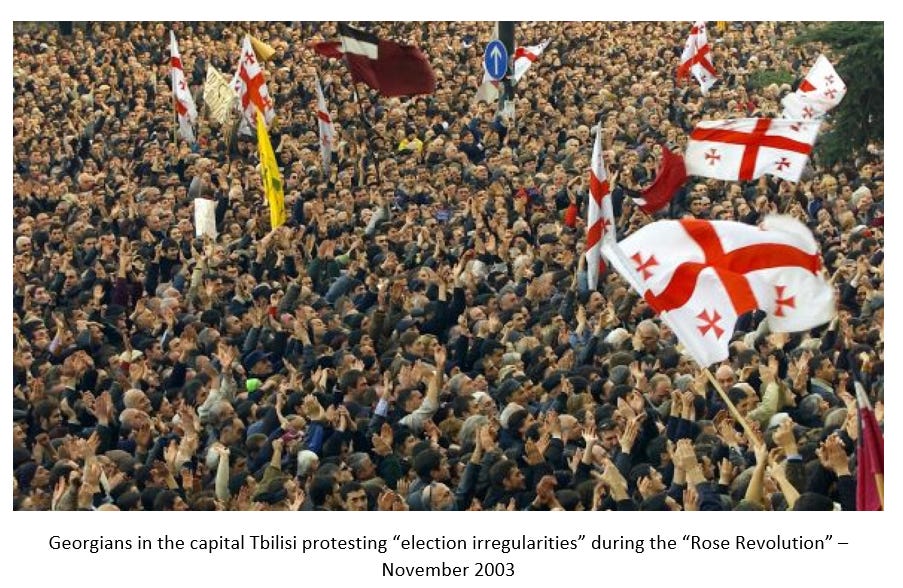

On the 23rd of November, 2003 at 8pm local Tbilisi time, history was made: Eduard Shevardnadze, the former Soviet Foreign Minister and then current President of the Republic of Georgia agreed to step down from office, handing the reins over to the Parliamentary Speaker for an interim period until fresh elections could be held.

Shevardnadze’s capitulation signaled the end of what became known as the “Rose Revolution”, a three-week long series of demonstrations protesting against a perceived rigged election, on top of anger at endemic corruption, poverty, and the small Caucasian country’s inability to exert sovereignty over the whole of its internationally-recognized territory. In a deal between Shevardnadze and opposition leader Mikhail Saakashvili brokered by Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov, the President would vacate office immediately in return for security assurances from demonstrators who threatened to physically confront him at his residence.

The ‘wily’ old communist fossil was gone and Georgia was now firmly on the path towards liberal democracy, prosperity, and freedom. US Secretary of State Colin Powell quickly called Acting President Nino Burdzhanadze to offer American support.1 The future looked so, so bright that late autumn evening. The Georgian people rose up all on their own and overthrew an authoritarian leader in the name of democracy. It was like 1989 all over again…..or so we were told at the time.

Many of you are well-versed in the stories of what has become to be known as “Colour Revolutions”, and some of you were present during their various manifestations, with a few of you possibly having participated in them. It wasn’t until the Rose Revolution that people began to really catch on to the role played by the USA (and its many tentacles), as we were so much more naive then in comparison to now. This is not to say that these rebellions were entirely without justification (more on this later), as all the targeted countries were experiencing the growing pains of post-communist transition to democracy.

What this second entry in this series intends to do is to put the first few attempts (and successes) at regime change in post-communist Europe into a larger context. Later entries will deal with the nuts and the bolts, so please have some patience with me as I jump from one location to another, one moment in time to the next (or “come unstuck in time” as per Kurt Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse Five).

Nature Abhors a Vacuum

This story begins with a simple misunderstanding.

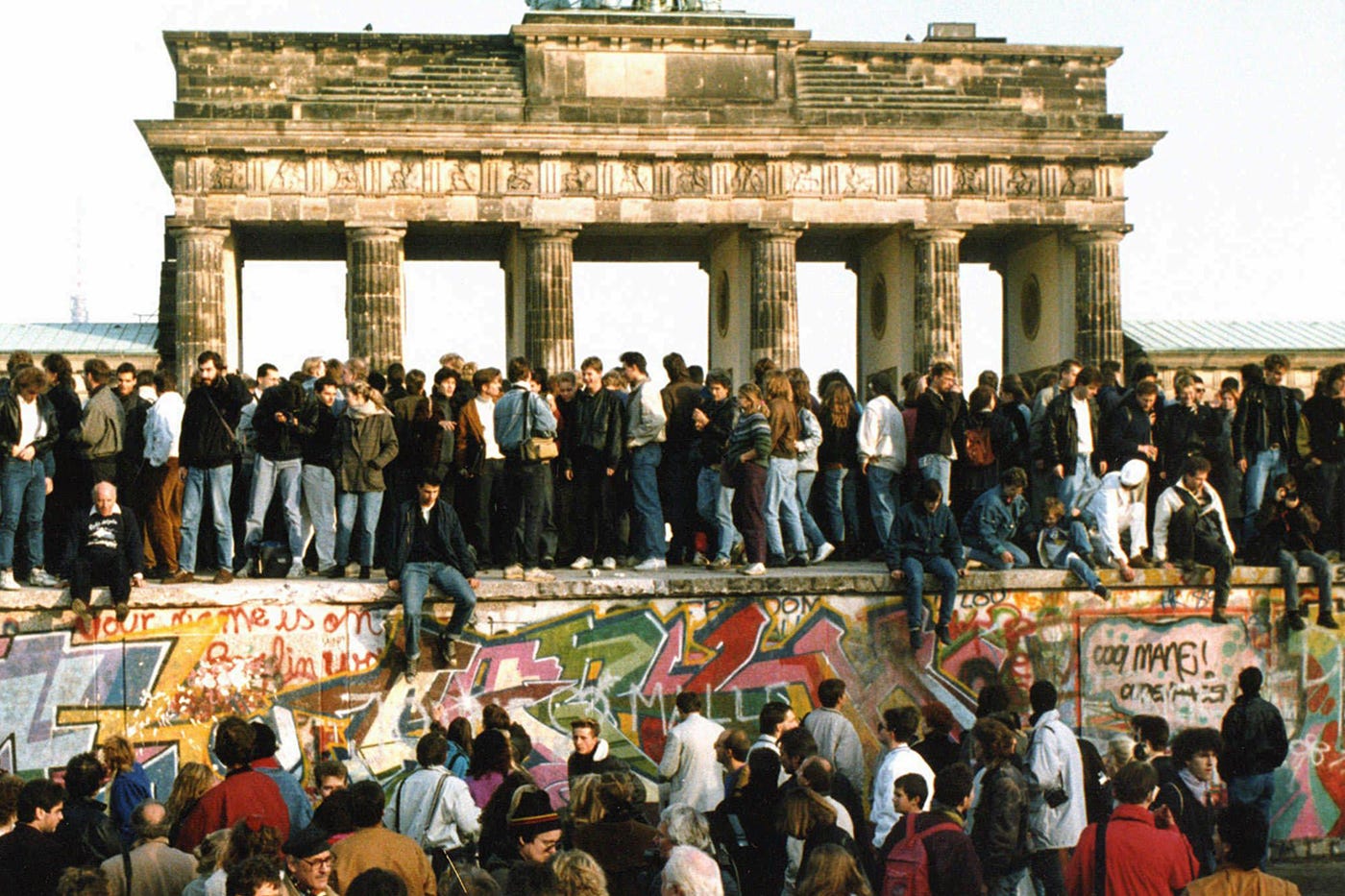

1989 was a heady time to be alive. Millions of us were glued to our TV screens every night, watching and absorbing the images of Europeans stuck behind the Iron Curtain taking on their dictatorial regimes. For us Cold War kids, the division between the western and eastern blocs seemed a permanent feature of life, so much so that even in 1988 few people could have imagined what was coming only one year later.

We in the west were the good guys. The regimes in the east were the bad guys. Simple as. We had freedom, liberty, rights, and prosperity. We also had a future. They had dictatorships, stagnation, oppression, lower standards of living, and horrible, horrible consumer products. Those stuck behind the Iron Curtain wanted Levi’s Jeans, Converse running shoes, Rock’n’Roll, and the right to travel. We wanted nothing from them at all. Our system was “superior” in every way.

We watched every night as the dominoes began to fall in reverse: Poland, Hungary, and then East Germany, followed by Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and finally, Romania. For the most part, these were bloodless revolutions (made possible by Mikhail Gorbachev’s liberalization), which showed that these regimes had no popular mandate, and no legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens. The entire house of cards had collapsed.

The images beamed into our homes showed us that the people out in the streets were demanding democracy. They wanted the vote. “Wow, they’re just like us!”, we thought. The desire to control your own destiny is a universal one, so we did not question these demands and assertions. It was entirely natural.

We did not know it at the time, but there was a confusion in the transmission: what western elites saw in these revolutions was people who wanted to become western and were demonstrating for individual rights like those present in the “free world”. What most of these demonstrators actually wanted was national freedom i.e. liberation from Soviet domination. It is this confusion which colours the political debates in these countries (and the breakaway Soviet republics, for the most part) to this day.

Nature abhors a vacuum. Gorbachev lifting his hands in response to the fall of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe meant that a new order was required to deal with these tectonic shifts. All of these countries quickly drafted new constitutions that embraced mulitiparty democracy, with an eye cast towards Brussels, as the EC (European Community) was headed towards the Maastricht Treaty that would create a new entity called the European Union to supplant it, one that would be much more integrated, political, and stronger than its predecessor. Not part of a up-until-then non-existent EU, and no longer part of the Eastern Bloc, these newly-freed countries were left to their own devices. They were independent.

The Americans had different ideas. Watching the USSR pull back from Central and Eastern Europe and turn inwards in an effort to save its own system, the USA was giving assurances to Mikhail Gorbachev that it would not expand NATO into the former Warsaw Pact states. This is still a controversial matter in the west, but the case was closed some time ago:

Washington D.C., December 12, 2017 – U.S. Secretary of State James Baker’s famous “not one inch eastward” assurance about NATO expansion in his meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, was part of a cascade of assurances about Soviet security given by Western leaders to Gorbachev and other Soviet officials throughout the process of German unification in 1990 and on into 1991, according to declassified U.S., Soviet, German, British and French documents posted today by the National Security Archive at George Washington University (http://nsarchive.gwu.edu).

The documents show that multiple national leaders were considering and rejecting Central and Eastern European membership in NATO as of early 1990 and through 1991, that discussions of NATO in the context of German unification negotiations in 1990 were not at all narrowly limited to the status of East German territory, and that subsequent Soviet and Russian complaints about being misled about NATO expansion were founded in written contemporaneous memcons and telcons at the highest levels.

The documents reinforce former CIA Director Robert Gates’s criticism of “pressing ahead with expansion of NATO eastward [in the 1990s], when Gorbachev and others were led to believe that wouldn’t happen.”[1] The key phrase, buttressed by the documents, is “led to believe.”

President George H.W. Bush had assured Gorbachev during the Malta summit in December 1989 that the U.S. would not take advantage (“I have not jumped up and down on the Berlin Wall”) of the revolutions in Eastern Europe to harm Soviet interests; but neither Bush nor Gorbachev at that point (or for that matter, West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl) expected so soon the collapse of East Germany or the speed of German unification.[2]

The first concrete assurances by Western leaders on NATO began on January 31, 1990, when West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher opened the bidding with a major public speech at Tutzing, in Bavaria, on German unification. The U.S. Embassy in Bonn (see Document 1) informed Washington that Genscher made clear “that the changes in Eastern Europe and the German unification process must not lead to an ‘impairment of Soviet security interests.’ Therefore, NATO should rule out an ‘expansion of its territory towards the east, i.e. moving it closer to the Soviet borders.’” The Bonn cable also noted Genscher’s proposal to leave the East German territory out of NATO military structures even in a unified Germany in NATO.

The security vacuum had to be filled, and the Americans decided that NATO would be best suited to do it. The fact that it would move NATO forces closer to the USSR’s borders was purely a coincidence.

In November of 1993, George Soros published an essay on NATO and its role in the “New Order”. Here are some highlights:

We need a totally different conceptual framework for dealing with this situation, because it involves not only relationships between states but also relationships within states, or what used to be states.

…………

I should like to put before you a conceptual framework in terms of which the present situation can be understood. It has two major components: one is a theory of history, with particular reference to revolutionary change, and the other is a distinction between open and closed societies. The two elements are interconnected—they share the same philosophical foundations—but the connection is not very strong. It is possible to distinguish between open and closed societies, as Karl Popper did, without any insight into the process of revolutionary change; and it is possible to use my theory of history without introducing the concepts of open and closed societies as I myself have done in my dealings in financial markets.

……

This brings me to the second part of my conceptual framework. To understand the current situation, I contend that it is very useful to draw a distinction between open and closed societies. The distinction is based on the same philosophical foundations as my theory of history, namely, that participants act on the basis of imperfect understanding. Open society is based on the recognition of this principle and closed society on its denial. In a closed society, there is an authority which is the dispenser of the ultimate truth; open society does not recognize such authority even if it recognizes the rule of law and the sovereignty of the state. The state is not based on a dogma and society is not dominated by the state. The government is elected by the people and it can be changed. Above all, there is respect for minorities and minority opinions.

……

The collapse of the Soviet empire has created a collective security problem of the utmost gravity. Without a new world order, there will be disorder; that much is clear. But who will act as the world’s policeman? That is the question that needs to be answered.

…….

The United Nations might have become an effective organization if it were under the leadership of two superpowers cooperating with each other. As it is, the United Nations has already failed as an institution which could be put in charge of U.S. troops. This leaves NATO as the only institution of collective security that has not failed, because it has not been tried. NATO has the potential of serving as the basis of a new world order in that part of the world which is most in need of order and stability. But it can do so only if its mission is redefined. There is an urgent need for some profound new thinking with regard to NATO.

………

The original mission was to defend the free world against the Soviet empire. That mission is obsolete; but the collapse of the Soviet empire has left a security vacuum which has the potential of turning into a “black hole.” This presents a different kind of threat than the Soviet empire did.

………….

Closed societies based on nationalist principles constitute a threat to security because they need an enemy, either outside or within. But the threat is very different in character from the one NATO was constructed to confront, and a very different approach is required to combat this threat. It involves the building of democratic states and open societies and embedding them in a structure which precludes certain kinds of behavior. Only in case of failure does the prospect of military intervention arise. The constructive, open society building part of the mission is all the more important because the prospect of NATO members intervening militarily in this troubled part of the world is very remote. Bosnia is ample proof.

……

NATO has a unified command structure which brings together the United States and Western Europe. There are great advantages in having such a strong Western pillar: it leads to a lopsided structure firmly rooted in the West. This is as it should be since the goal is to reinforce and gratify the desire of the region for joining the open society of the West.

It would be an express condition of membership in the Partnership for Peace that NATO is free to invite any member country to join NATO. This would avoid any conflict that could arise either from the enlargement of NATO against the wishes of Russia or from giving Russia veto over NATO membership. The specter of the past looms large: one must avoid the suspicion of either a new “cordon sanitaire” or a new Yalta. A Partnership for Peace along the lines outlined here would avoid both suspicions. It must be attractive enough to induce Russia to subscribe. It if does, there is nothing to prevent countries like Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary from being admitted to some form of membership in NATO, the character of which would depend on their internal development.

Note: Ex-NATO Chief George Robertson recently admitted that Vladimir Putin requested NATO membership for Russia early on in his Presidency, only to be rebuffed.

Also please note the bolded portions in the excerpts above. In particular, I want you to remember the following:

Karl Popper and The Open Society

“Respect for minorities and minority opinions”

NATO as the only institution that can guarantee collective security

“nationalist principles constitute a threat to security”

building of democratic states and open societies and embedding them in a structure which precludes certain kinds of behavior

All of these elements will appear in the various revolutions that will be covered in this series. The disingenuous liberal who will charge me with being a “conspiracy theorist” or “anti-semite” (or both, most likely) will ask: “George Soros is a private citizen and philanthropist. He was unelected then and still is. What kind of effect can he have on US foreign policy?”