Previous Entry - Serbia’s “Bulldozer Revolution” (2000)

“Hard times create strong men. Strong men create good times. Good times create weak men. And, weak men create hard times.”

-G. Michael Hopf in “Those Who Remain”

This very Spenglerian view of history appeals to many people, which is why this quote has taken on a life of its own on the internet these past few years. It assumes that ‘good times’ are actually possible, that they have existed in the past, or that they can happen again in the future. The optimism implied in the quote immediately betrays the author’s western background, as life in the West has for long stretches been ‘good’.

Although finding fertile new ground in the USA, cynicism has historically been the preserve of others; those from historically rough neighbourhoods. The Slavlands are one of these, which is why the quote was recently amended like this:

Slavs are cynics, and with good reason. It’s not easy living in a tough neighbourhood.

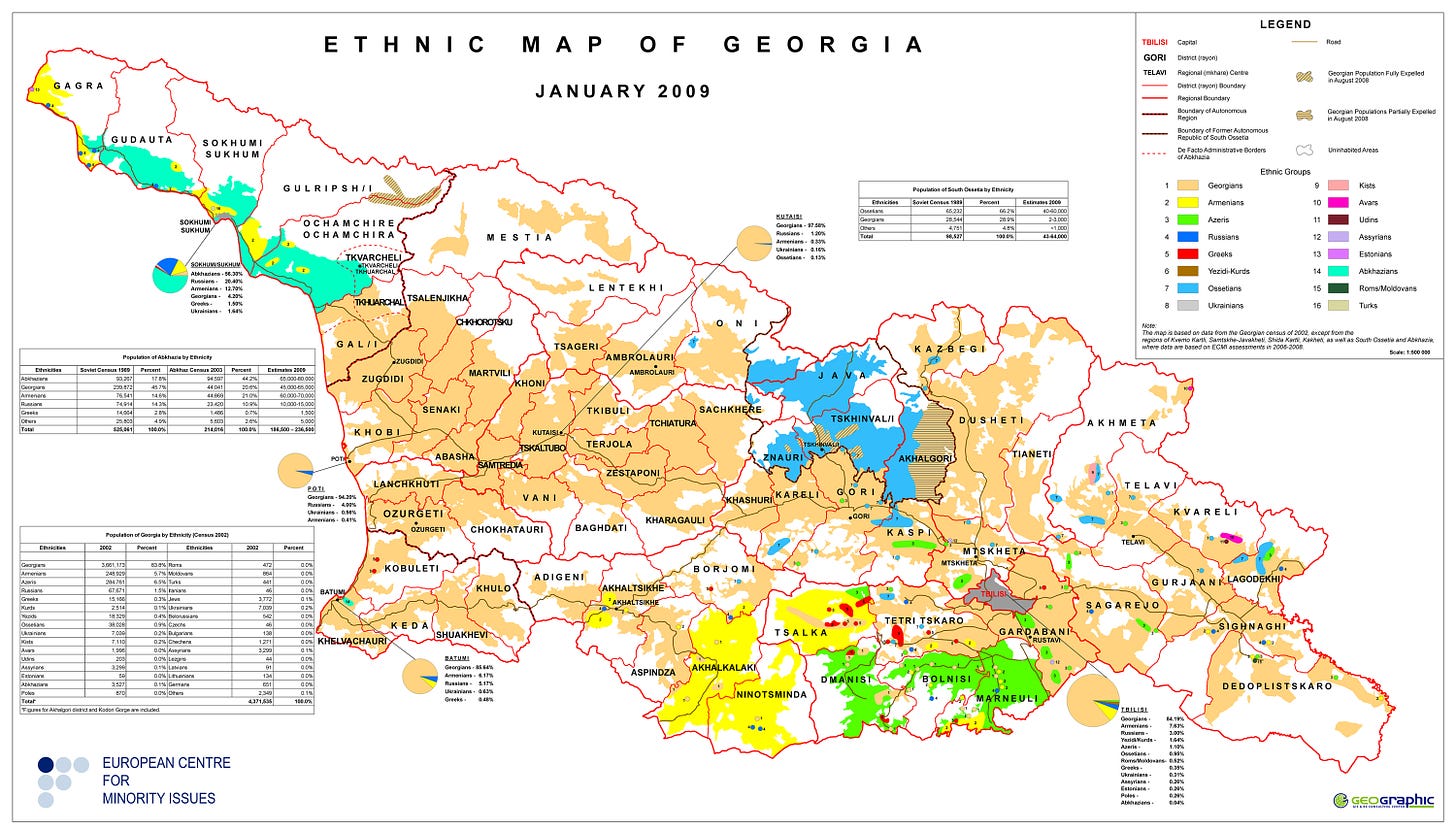

Another tough neighbourhood is the Caucasus, nestled between Russia’s Slavlands and both Turkey and Iran. If you think that the Balkan Peninsula is ethnically complex, take a glance at this map:

This mess is a product of three main factors:

the geography of the region, whereby it has historically been a corridor for migrations of peoples alongside mountain valleys serving as pockets that preserve ethno-linguistic features, differentiating people at a micro-level

the civilizational struggles between the empires that have bordered it, fought over it, and have conquered and ruled it

the establishment of republican borders during the early Soviet era1, creating even more divisions, often nonsensical from an outside perspective2

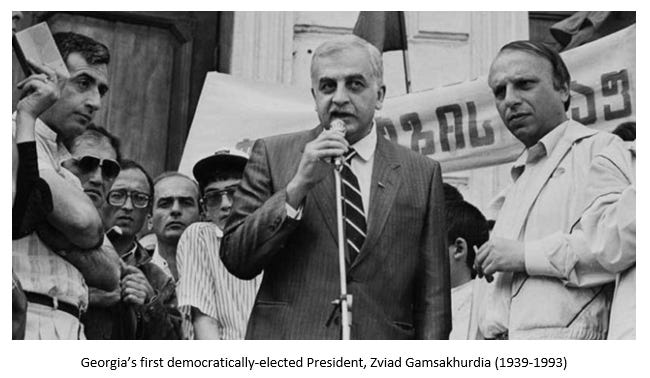

Only the tough can survive here, and only the toughest have. It’s no wonder that the Caucasus have consistently produced "strong men” throughout history, Georgia specifically. This tiny land in the 20th century alone put onto the world stage the powerful NKVD Chief Lavrenti Beria (an ethnic Mingrelian from what is now part of the breakaway Georgian region of Abkhazia), the mighty Bolshevik and Soviet politician Sergo Ordzhonikidze, the final Soviet Foreign Minister (and later, Georgian President) Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia’s first democratically-elected President Zviad Gamsakhurdia, and most significantly of all, Soviet dictator Ioseb Dzhugashvili aka “Stalin”.

“Democracy” is a relative concept in this part of the world, with authoritarianism the general rule historically. Making matters more difficult is that this collection of states and provinces must constantly swim against nasty geopolitical currents that toss them from one side to the next thanks to great power politics. National sovereignty for most of the peoples of the Caucasus has never realistically been within reach, leading the various ethnic and religious groups to try and maximize their autonomy (in varying degrees) by siding with one larger power against another when the opportunity has presented itself to do so. This is THE political theme of this hardscrabble region, one that persists to this day.

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) aka Russia’s “Near Abroad”

The Cold War initially saw the world divided into two spheres of influence: the “free world” (western democracies and their allies/subjects), and the “communist bloc”. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union saw the communist bloc ironically relegated to the “dustbin of history”. Russia, the inheritor to the now-defunct Soviet Union, accepted this. It also assumed that it would retain its own sphere of influence, albeit truncated, as Soviet forces withdrew from Central and Eastern Europe.

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) was born on the ashes of the USSR, with 12 of its 15 successor states becoming members (the Baltic republics opted out). This regional organization was to serve as a military and economic alliance to replace the previous Soviet Union. Russia viewed the territory of its eleven organizational co-members as part of its own sphere of influence.

The coordinated effort to remove Vladimir Meciar from power in Slovakia did not raise many alarms in Moscow, as 1998 was a very bad year for Russia politically, economically, culturally, and socially. What did scare Russia was the American bombing of rump Yugoslavia a year later, one that culminated in the peeling off of Kosovo from Serbia.3 It was this act, one without formal authority from the United Nations4, that moved the Russian Siloviki towards reasserting power in Moscow as quickly as possible. The overthrow of Slobodan Milosevic one year later only confirmed their worst suspicions.

Vladimir Putin’s rise to the top happened between the latter two events. Russia (already worried by NATO encroachment on its borders), knowing that it could do nothing about Yugoslavia beyond some symbolic public gestures, accepted the new regime as a fait accompli. After all, Yugoslavia left the Soviet orbit in 1948. This wasn’t Russia’s turf.

What was Russia’s turf was its “near abroad”, the independent states that came about due to the dissolution of the USSR.5 Western bombing or even regime change courtesy of western governments and their intelligence services would simply not be allowed in this zone. This was Russia's home stadium....at least according to Moscow.

Georgia 1989-2003: Secession, Independence, and Civil Conflict on the Road towards the Rose Revolution

Ask anyone from a post-communist country (excluding Russia for very specific reasons) how they felt on the eve of their homeland’s transition to democracy, and almost all of them will describe a naive optimism that manifested itself in enthusiasm and relief. Enthusiasm derived from long-awaited systemic changes that would empower them, relief stemming from the fact that it was finally happening.

All of these countries had regime dissidents, some of whom were locked up, many others stripped of their liberties and rights, with still more living in far away exile. All of these countries also had significant diaspora communities which were overwhelmingly (and in some cases, unanimously) anti-communist, often fanatically so. The optimism on the eve of the transition to democracy led most to believe that not just communism was on its way out, so too would be the communists that ran the oppressive system. What we learned after the collapse of communism quickly disabused us of those notions.

First, someone on their side had to agree to pull the plug on the communist system. Secondly, we realized that even though the communists understood the inevitability of the system’s collapse and the need to reform, they and their families would not necessarily be willing to give up actual political, economic, and institutional power as readily as they did communism.

We also came to understand that many of these communists were communists in name only. A significant chunk of them (often the majority) were non-ideological party members who sought personal and professional advancement. The only way towards a good life under communism was to join the party, even if you didn’t believe in Marxism. This went on to create a lot of confusion because many of these communists transformed overnight into nationalists or liberal democrats, etc. Who was sincere? Who was opportunistic? In many cases, we still don’t know to this day.

Lastly, we came to realize that someone needed to operate the machinery of the state. Who knew how to run the bureaucracy? The secret police? The army? Many of those employed by the state to run the country seamlessly segued from communism to democracy due to the simple fact that they knew how to do their own job as they had been doing it for years already.

Anti-communist dissidents dreamed of lustration, with the most adamant hoping to see communist officials tried and imprisoned for crimes committed under communism. Lustration saw only limited success, with the Czech Republic6 and Poland7 reportedly achieving the greatest results in ridding their state apparatus of former communist officials tainted by their actions under those regimes. Dissident daydreams of lustration proved a fantasy as anti-communists realized that they would have to compromise with ex-communists, lest their country spiral down towards civil conflict.

Zviad Gamsakhurdia “The Uncompromising”

One dissident who rejected compromise with ex-communists was Georgia’s first democratically-elected President, Zviad Gamsakhurdia. A ferocious Georgian nationalist from a very early age, he was never tainted with membership in the Communist Party. Imprisoned at times during the Soviet era, he was under the watchful eye of the KGB the rest of the time as he worked underground to promote human rights and Georgian interests.

As the Soviet system began to crumble during the Gorbachev era, he also began to organize anti-regime protests in Tbilisi. The growing series of anti-communist protests culminated in what became known as the “Tbilisi Massacre”. On April 9, 1989, local communist officials called in the Soviet Interior Ministry troops to quell the demonstrations, resulting in the deaths of 21 Georgians (17 of whom were female).

This massacre had the effect of giving a massive boost to calls for Georgian independence from the Soviet Union. Protests grew louder and louder, forcing the Georgian Communist Party to relent and introduce multiparty elections for the first time in its Soviet history. A coalition of nationalists and other anti-communists headed by Gamsakhurdia won a majority in Parliament, propelling him to the position of head of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia. He quickly called a referendum on leaving the USSR that passed with almost 99% of the vote (due to a boycott by most ethnic non-Georgians), leading Georgia to declare independence on April 9, 1991. Shortly thereafter, he was elected its first President.

In the meantime, Georgia was falling apart.

Like several other post-Soviet republics, ethnic conflicts boiled over post-independence as the communist dictatorship that kept a tight lid on them was removed. Warfare had erupted between Armenia and Azerbaijan, while Russians and Ukrainians in Trans-Dniester set up their own administration, independent of Moldova.

Georgia also fell victim to ethnic violence, as local leaders in Abkhazia and South Ossetia helped themselves to the massive Soviet-era military arsenals scattered across the post-Soviet space to erect their own secessionist political entities. In the northwest, the Abkhazians had their own Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic during the USSR, and were making moves to secede from independent Georgia. Closer to Tbilisi, the Ossetians had their own autonomous oblast, right across the border from the North Ossetian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, then and now part of the Russian Federation.

The Ossetians declared a “Soviet Democratic Republic” in September of 1990, one that would be “loyal to Moscow”. Retaliation arrived on December 11, 1990 when Gamsakhurdia suspended South Ossetia’s autonomy, putting it under the direct control of the central government in Tbilisi. This led to a war between South Ossetian separatists and Ossetian volunteers from North Ossetia on one side against Georgian authorities and ethnic Georgian militias on the other. At the time, South Ossetia was roughly 2/3rds ethnic Ossetian, and 3/10ths Georgian.8

Unlike the Ossetians in South Ossetia, the Abkhaz were not the majority (nor even the plurality) in their own autonomous entity. According to the 1989 Soviet census, Georgians comprised 45.7% of the population of the Abkhazian ASSR, with the Abkhaz making up only 17.8% of the overall total.9 Abkhazia was a victim of Stalin-era forced migrations and resettlement of peoples that significantly inflated the proportion of Georgians, Armenians, Greeks, and Russians in the autonomous republic. Abkhaz nationalists, decrying “population replacement” after decades of silence during the communist era, opposed Georgian independence as they feared it would result in the loss of their autonomy.10

Gamsakhurdia insisted on the removal of all Soviet legacy in Georgia, whether political, economic, cultural, or military. This drew the ire of Moscow and allowed Russia to play Georgians off against the restless minorities in the newly-independent country. Both the Ossetians of South Ossetia and the Abkhaz increasingly viewed Russia as their protector, one that would preserve their respective autonomies. At the same time, Soviet armed forces were still on Georgian soil, infuriating Gamsakhurdia and his supporters who insisted on their immediate removal.

Matters were made worse for Gamsakhurdia as he began to be challenged by those to his political right; the ultra-nationalists who thought that he was being too soft on the Abkhaz and Ossetian separatists, and on the Russians as well. They and others decried him as an "autocrat", "dictator", and "totalitarian". To top it all off, US-based NGO Helsinki Watch issued a damning report criticizing him for “violating the rights of freedom of assembly, speech, and the press”, as well as for “human rights abuses committed by the government and Georgian militias in South Ossetia”.11 Zviad was being boxed in on all sides.

Cracks began to appear in the state’s security services and National Guard, with pro and anti-government lines being drawn. Nationalist paramilitaries camped out near the capital, ready to take down the President. They moved against the parliament building on December 22, 1991, in a coup d'état that eventually toppled Gamsakhurdia two weeks later. Georgia’s first democratically-elected President fled first to Armenia, and then to separatist Chechnya.

The militants now in control of Georgia installed former Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze into office as de facto President in order to boost the image of the country, presenting it as being secure in the hands of the widely-respected elder statesman. Shevardnadze quickly utilized his paramilitary backers to “root out Zviadism”, as diehard Gamsakhurdia supporters continued to attack Georgian officials and security units. Government forces were sent into Abkhazia to hunt down supporters of Gamsakhurdia who were sheltering there. This boomeranged on Tbilisi, sparking renewed ethnic violence between Georgians and Abkhazians, leading to the victory of Abkhaz forces, the declaration of Abkhazian independence, and the ethnic cleansing of Georgians.

Gamsakhurdia took the opportunity to return to Georgia and challenge Shevardnadze’s rule head on. Launching a rebellion in the west of the country, his rebels pushed pro-government forces back towards Tbilisi. With the government teetering on the verge of collapse, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia decided to intervene, with the Russians committing 2,000 soldiers to support the fading government forces. The tide quickly turned and the rebel forces collapsed. Gamsakhurdia died under very mysterious circumstances on December 31, 1993, with some suggesting that he committed suicide, while others insisting that he was assassinated by Georgian state security.12