"Patient Zero", Part 1

Gaetan Dugas, the CDC Cluster Study, Denial, Defiance, Rumours, Community-based Fears, Pariah Status

Previous Entry - 1979-1982: The Initial Medical Establishment Reaction

It was about this time that Steve Del Re, the young man who had so bitterly chastised Conant for wanting to close the baths, appeared in Conant’s office. By now, Conant had heard the rumors about the twenty-seven-year-old’s liaison with Rock Hudson, but Steve hadn’t come to gossip.

“I have this purple spot,” he said.1

We humans are a diverse lot, psychologically speaking. When the news about COVID-19 hit the airwaves, I immediately supported the idea of a total lockdown and closed borders for three weeks at minimum in order to minimize exposure to the virus, and to buy time to see what we could learn from what was happening in China and elsewhere.

Others reacted differently. We can’t forget how some politicians chastised us as “racists” for daring to make the above suggestions, with some going as far as engaging in public displays of physical affection with Chinese people in their countries in order to show everyone that it was harmless to do so. At this point in the pandemic the virus was still an abstraction, allowing people a wider range of options in terms of how they chose to react while they processed new information that was being delivered to us.

Like any tragedy, things become real and no longer abstract once the bodies start to pile up. The excerpt above details how a young gay man was transformed overnight from being adamantly opposed to the closure of the bathhouses in San Francisco, to realizing that he was ill and was going to die. Denial about AIDS led this man to reject the existential danger that it posed not just to him, but to his community, because he put their freedom (and politics) above public health. I am not equating HIV to COVID-19, as the two are very, very different re: mortality at the beginning of their respective historical spreads. What I am saying is that human psychology is a constant, and the diversity of reactions to tragedies will shape and form our reactions to it.

Everyone reading this is aware of the 5 psychological stages of grief and facing tragic news, and these apply to HIV/AIDS just like they do to any other tragedy. Denial is both natural and easy particularly when a threat is abstract. Despite warnings by some gay men that something new and deadly was out there, we saw how most continued to party as if no danger was posed to them. When the rising body count began to include those that they knew, denial quickly turned to anger.

People do not like being exposed to anger, especially when it is targeted towards them. “Don’t be so angry!”, is a standard response when confronted with it. Yet anger can play a positive role, as it can help clarify an issue, concentrate people’s attention on a particular subject, and mobilize them to act upon it. Anger is what drove Larry Kramer for example, and anger was the engine that earned wins for his organization “ACT UP” later in the same decade.

Human psychology also requires a face around which to rally against when angry. This is the scapegoat. Emmanuel Goldstein served as a fictional scapegoat and stand-in for Leon Trotsky in George Orwell’s 1984. Bruce Ismay, Chairman and Managing Director of White Star Line, is a real life example of a scapegoat who died as a pariah in seclusion 25 years after the sinking of the Titanic. In the case of AIDS, there were two major scapegoats: Ronald Reagan and a gay man named Gaetan Dugas.2

The next two entries will deal with Gaetan Dugas, specifically focusing on his role in helping the CDC discover how HIV was spread, his posthumous scapegoating, and his rehabilitation thanks to more recent scientific discoveries. We will also measure this rehabilitation against contemporary reports from people who interacted with Gaetan in order to try and gain a clearer picture of a man who has become an unwitting historical villain and legend.

The CDC Cluster Study

Picking up from where we last left off, public health officials at the local, state, and federal levels were left racing trying to solve a mystery worthy of Poirot or Agatha Christie: What is the cause of these diseases? How are they being spread? And why are gay men so overwhelmingly represented among the infected?

The CDC rolled into action in July 1981, setting up the CDC Taskforce on Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections (KSOI) under Jim Curran, who recruited an “all-star team” which included notables like Mary Guinan, Harold Jaffe, and sociologist William Darrow, the only non-medical specialist involved.3 Our hero, Selma Dritz, also made the roster. Darrow's first act was to draw up a 21-page questionnaire (I have never seen it, btw) in order to set up a case-control study. There were 62 questions in total, with 8 physicians interviewing 50 "GRID patients" and 120 controls from September to November of that same year.

Thanks to the openness and honesty of the participants in the interviews (it was reported at the time that the subjects were happy to speak at length about their sexual and social histories), Darrow and his team created a profile of a typical “GRID patient”: an “openly gay man in his 30s who enjoyed an energetic sex life based around bars and bathhouses for some years, and who used “poppers”.4 Poppers were quickly ruled out as a cause for the diseases spreading throughout the community, with the rest of the data confirming the suspicions of the researchers; that this was an infectious agent, most likely a new sexually-transmitted disease.

Data began to pour into the CDC in Atlanta from New York City, Los Angeles and San Francisco, including definitions relations between those early patients:

On March 3, 1982, Bill Darrow sent Jim Curran a memorandum about time-

space clustering of cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma, 16 in which he mapped out all the

cases of KS reported from Manhattan up to the start of 1982, and illustrated

that, with four exceptions, they all came from either the Greenwich Village area

or the Upper West Side. In the same memorandum, Darrow analyzed the first

fifteen cases of KS in New York males, all of which had a date of onset before

1980. Most of these men identified the same places as favorite pickup spots:

bathhouses such as the St. Mark’s, Everard, the Club, and Dakota, bars such as

the Mineshaft, “action stores” such as the Christopher Street Book Shop,17 and

parks — most notably that in Washington Square.5

When Darrow combined this information from NYC with that which he received from Los Angeles, he found first person sexual contacts between affected patients on both coasts. This gave birth to the CDC Cluster Study:6

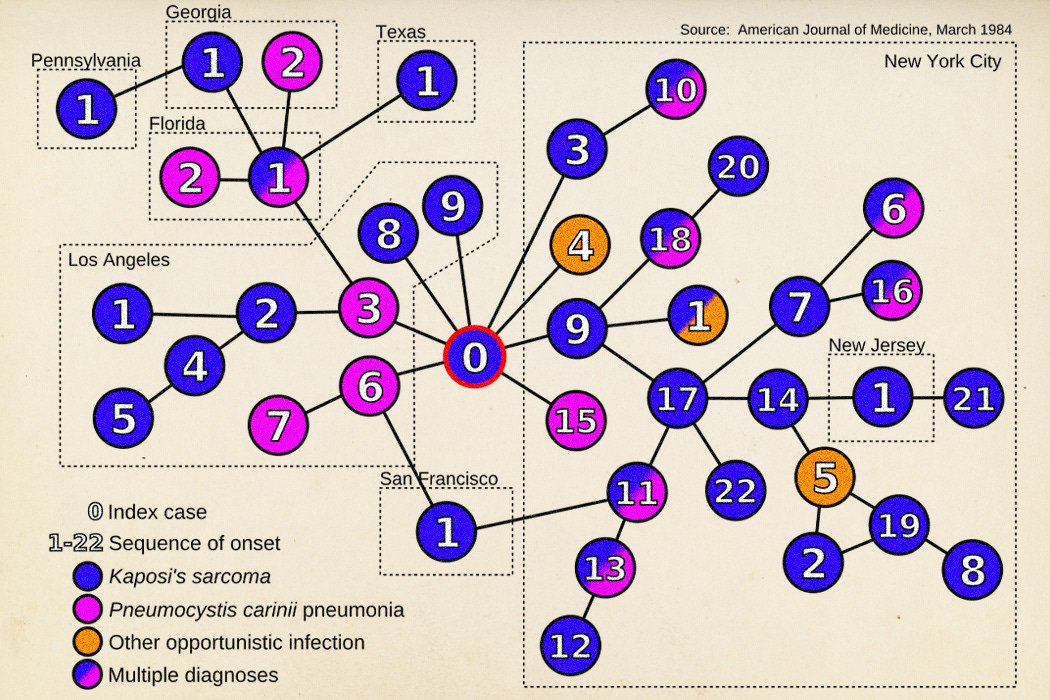

The “O” (out-of-California) at the centre of the cluster study represents Gaetan Dugas:

One of the dead men from the pool party (who would later be given the cluster study code LA2), turned out to have had sex with two other men who also had GRID, one of whom was an air steward (LA1), who had traveled widely around the world in the previous six years: in 1976 to Kenya and Tanzania, in 1977 to Italy and Greece, and in 1978 to France and England. 20 Soon afterward it became apparent that one of the other dead men from the pool party, LA3, had also had sex with an air steward who was suffering from KS, and that this man, a Canadian, had himself had sex with three other Los Angelinos with GRID. At long last, there was hard evidence to support the oft suspected theory of causation. GRID appeared to be caused by an infectious, sexually transmitted agent, most probably a virus.

As in a reversed loop of film, the whole tumbling cascade of cards suddenly —

and surprisingly — re-formed into a neat deck. The Canadian air steward, Gaetan

Dugas,* who was given the code “Patient O” (since, as regards the Los Angeles

cluster study, he was the patient from “Out of California”), turned out to have also

had sex with a further four GRID patients from New York. This placed Dugas at

the hub of a wheel that had eight gay men with AIDS around its rim, with each of

whom he had had sex between 1978 and December 1980.21 These eight were, in

turn, connected by sexual contact to another thirty-one, thus placing Patient O at

the center of a group of forty AIDS cases, representing almost one-sixth of the 248

U.S. cases then reported. Given Dugas’s apparently central role in the cluster, it

was not long before everyone involved in the research, including the CDC people,

abandoned “Patient O” for the rather more graphic sobriquet of “Patient Zero.”7

Patient O became Patient 0, then morphing one last time into ‘Patient Zero’.