The Early Days of HIV/AIDS - 1979-1982: The Initial Medical Establishment Reaction

Physicians, Epidemiologists, and Public Health Officials Roll Into Action, CDC on Alert, MMWR Article as Anno Domini of HIV, First Known Cases, Gay Culture Meets Medical Establishment

Previous Entry - 1979-1981: “Watch out guys, there’s something out there!”

A little over a decade ago, I was knee-deep in geneaological research and came across data that introduced me to the fact that a plague had hit my side of the county of my birth during the last three years of the Napoleonic Era. One branch of my ancestry saw three generations of direct ancestors, both male and female, almost entirely obliterated over the course of that short time span. The village in which I lived the first part of my life was so devastated that it never managed to recover its population level even into the late 20th century. My paternal line was at that time across the valley (where the plague was somewhat more forgiving), allowing one of my direct paternal ancestors to make the move after the coast was clear, as a lot of farmland was freed up for survivors to take over and make their own.

When you take a look at the histories of cities in the ancient, medieval, or more recent periods, one will often see how plagues would often empty out cities, slashing their populations by a third, or half, or even more, requiring immigrants from the hinterland to bring it back to life. This would happen time and time again, if the cities weren’t totally abandoned, like many were. Add to this poor medical practices and a brutally high rate of infant mortality, and it’s little wonder why Europe’s population remained static for long periods of time.

The great advances in medical knowledge and practices in the 19th century paired up with the increasing insistence on better personal and public hygiene to make outbreaks much less frequent than they once were. Still, outbreaks of disease continued to pop up, with the Spanish Flu of 1918 being a particularly costly one, causing 50 million deaths (one of my great-grandfathers among them, the “rich” one!) out of 500 million estimated cases worldwide. Despite that catastrophe, plagues and mass disease were becoming something that increasingly healthy and affluent westerners assigned to the “rest of the world”.

Nevertheless, several polio epidemics shook the USA from 1948-1955, reminding Americans that they were never totally safe. However, Dr. Jonas Salk rode to the rescue with his vaccine to save the day. Modern medicine was a miracle, and was something that could be trusted, provided that you had access to it. Penicillin was the best example of this medical revolution.

It was penicillin that gay men (and those treating them) relied on during the 1970s as STDs exploded in number. Cheap to produce, safe to use, and very effective, this medicinal magic lulled not just gay men into a sense of security, but also a notable chunk of the medical establishment as well. Deadly epidemics were fading into collective memory, with the Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Philadelphia in 1976 being an outlier. Modern medicine was a marvel, and it could tackle more and more challenges that were once guaranteed death sentences.

As we saw in previous entries in this series, some medical practitioners and researchers were worried by the late 1970s with what they were seeing in sexually active gay men: increasing rates of both traditional and rare STDs spreading through their communities, alongside exotic diseases that should have neither been present in young men, or should have been particularly easy to fend off (or a combination of both). Epidemiologists, Infectious Disease Specialists, and doctors catering to gay male clientele expressed their concerns either privately among colleagues, or increasingly loudly with their patients and at conferences.

As we saw in last week’s entry, doctor’s began to note young gay men coming down with Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). The former was a cancer found previously only in males of Mediterranean descent and well into old age, while the latter was something that young, healthy people would easily flush out by way of a normal-functioning immune system. The fact that numbers were rising for both and were (then) entirely found within a very specific cohort (young gay men), led many doctors, nurses, and researchers to note these anomalies and to begin asking around to see if these were one-offs, or if others had seen these strange trends happening in their parts of the USA as well.

And it’s at this point that we will begin to dig into the sources to see just what doctors, nurses, and researchers thought and said upon being introduced to the notion that a new plague was spreading, and how they reacted to it as well. Some were better positioned to react due to their close relations with the gay community, either personally or professionally (and in some cases, both), while others had to do a lot of fast learning in order to understand just how different it was from the straight world.

This entry is going to be quote-heavy for the simple reason that first person accounts are high value, and that interviews and primary sources from which these excerpts are sourced from come from a time in which people could be much more frank and direct than they are today. “Clap Doctors”, Family Physicians, specialists and nurses at hospitals, researchers, public health officials, and the CDC will all be represented in order to cast as wide a net as possible to illustrate just how these medical professionals reacted to a new and deadly disease that was both unknown and very menacing.

The Medical Reaction

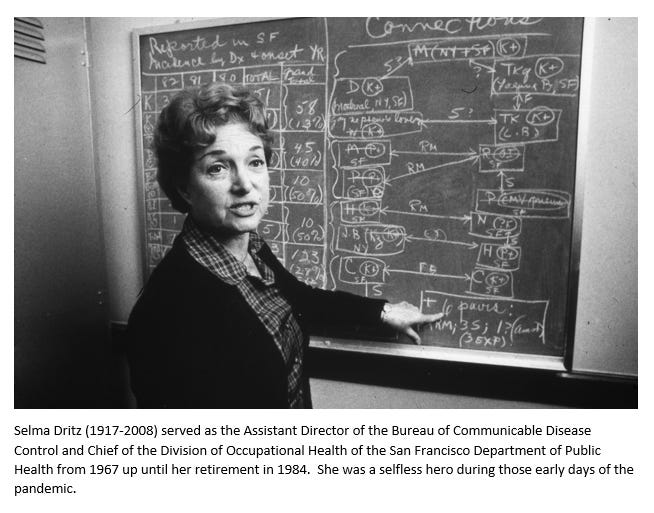

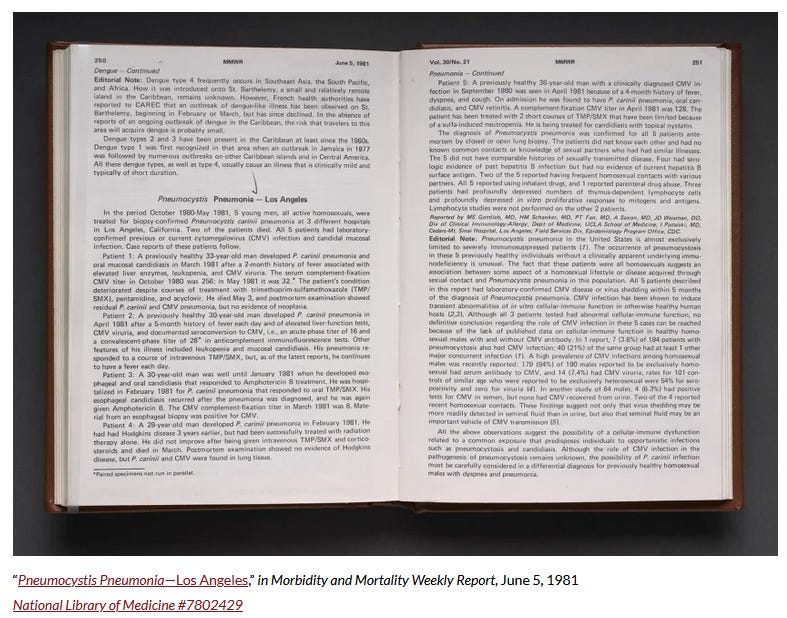

The BC/AD for the AIDS pandemic in North America is June 5, 1981, when Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR, a CDC publication) published an article entitled “Pneumocystis Pneumonia—Los Angeles” that described a “rare lung infection among a group of gay men…” in that city. As mentioned previously, others had already noted these odd/exotic diseases striking gay men, but this was the first article on record.

The report details the cases of five patients—all young and previously healthy gay men, with life threatening pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), an infection that rarely causes serious illness in healthy adults. Between October 1980 and May 1981, the patients sought care at three Los Angeles area hospitals, presenting with PCP and other, unusual opportunistic infections, like cytomegalovirus (CMV) and candidiasis. One patient had recovered from Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer that HIV positive people are at increased risk of developing, a few years prior. The editorial notes suggest that some cellular-immune deficiency was at work, although it was unclear what role PCP or CMV played in the dysfunction of the body’s defenses. Despite treatment, two patients had died at the time of publication. The remaining three would perish soon after.1

It was the publication of this article that caused the dam to break, as medical professionals across the country began to call one another on their phones, to report similar cases elsewhere, and to compare and contrast just what it was that they were seeing:

Within a day or two of Gottlieb’s report in the MMWR of June 1981, calls came

in from several doctors who believed that they had seen similar cases. Jim

Curran and Denis Jurannek flew up to New York City to see Alvin Friedman-

Kien and Linda Laubenstein, both to interview some of the thirty-one men with

KS and PCP whom they had on their books, and to get details on others who

had already died. They also spoke further with Fred Siegal, an immunologist at

Mount Sinai Medical Center, who had seen four gay men with chronic perianal

ulcers caused by Herpes simplex, only one of whom was still alive.10 When they

returned to Atlanta, Curran got together with Haverkos to draw up a working

case definition — one that was subsequently to be greatly enlarged, but that still

forms the basis of the AIDS clinical case definition of today.2

Reviewing the pathology logs and setting up a case control study:

Next, the task force members set about reviewing pathology logs from eigh-

teen major cities. They found that GRID cases were not spread throughout the

United States, but seemed to be cropping up almost exclusively in the four cen-

ters of New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Atlanta. At this stage, all the

cases were in gay men, and it was clearly of paramount importance to discover

why this group was — apparently uniquely — vulnerable to the syndrome. It

was thus that a few weeks later, sociologist Bill Darrow was requisitioned to join

the team.As soon as he arrived, he drew up the interview form for a case-control

study, a twenty-one-page questionnaire designed to establish the main risk

factors for GRID. Fortunately, one of the subjects that most intrigues “sex-

positive” people13 is their own sexual activity, and the eight physicians whom

Darrow trained in Atlanta during August and September apparently had little

difficulty persuading their interviewees to answer the sixty-two subdivided ques-

tions. From September to November 1981, his team interviewed fifty GRID

patients, and 120 controls (gay men without symptoms of GRID), from the

four key cities. They concluded that the main differences between cases and

controls were the number of sexual partners per year and the proportion of

those partners met in bathhouses. Also associated with illness were such factors

as having a history of sexually transmitted diseases, and exposure to feces —

notably during rimming and fisting.14 The typical GRID patient was an openly

gay man in his thirties, who had enjoyed an energetic sex life based around bars

and bathhouses for some years, and who used amyl nitrate “poppers” as a sex-

ual stimulant and relaxant.3

The task force members already knew the answer to their question as to what was causing the spread of these diseases, but could not just yet prove it:

None of these conclusions was unexpected. Indeed, by this stage, most of the

task force members were “willing to bet their salaries” that GRID was caused by

a new — or hitherto unrecognized — infectious agent. Alvin Friedman-Kien

and colleagues at the New York University Medical Center were beginning to

identify sexual connections between some of their GRID patients, but nobody

thus far had documented or proved such links.4

A small cluster of cases in Los Angeles confirmed their suspicions:

Shortly after this, Dave Auerbach phoned from Los Angeles with a fascinat-

ing story to tell. Darrow immediately flew out to join him, and during the next

few days they conducted the study that would effectively confirm the theory of

causation that most of the task force scientists, and several of the men suffering

from GRID, had long intuited.Darrow and Auerbach’s elegant case-cluster study has a fascinating back-

ground, which, were it not so tragic, would have all the makings of a Mensa

brainteaser. In October 1979, three long-established gay couples shared the

same table at a fund-raising dinner in Los Angeles. The following summer, two

of the couples attended a small party beside the backyard pool at one of their

houses; they also invited a male prostitute, described as “a $50 trick off Santa

Monica Boulevard.”19 During the evening, each of the five men had sex with

each of the others. Soon afterward, some of the men started feeling lethargic

and losing weight, and by March 1982, one of the partners from each of the

original three couples had died of AIDS. One of the surviving partners was so

concerned by the fact that each of the three men had died on the sixth day of

the month, resulting in the ominous figure “666,” that he called up Dave

Auerbach at the CDC.Darrow and Auerbach visited this man a few days later. Unimpressed by the

Beelzebub theory, they decided that the fact that only two of the deceased had

attended the backyard party confirmed that the cause of their deaths was

unlikely to be either environmental (like contaminated water in the swimming pool) or circumstantial (a bad lot of drugs). But then the real connections

began to emerge. One of the dead men from the pool party (who would later be

given the cluster study code LA2), turned out to have had sex with two other

men who also had GRID, one of whom was an air steward (LA1), who had trav-

eled widely around the world in the previous six years: in 1976 to Kenya and

Tanzania, in 1977 to Italy and Greece, and in 1978 to France and England. 20

Soon afterward it became apparent that one of the other dead men from the

pool party, LA3, had also had sex with an air steward who was suffering from

KS, and that this man, a Canadian, had himself had sex with three other Los

Angelinos with GRID. At long last, there was hard evidence to support the oft-

suspected theory of causation. GRID appeared to be caused by an infectious,

sexually transmitted agent, most probably a virus.5