The Early Days of HIV/AIDS - 1979-1981: “Watch out guys, there’s something out there!”

Worries, Early Alarms, Prolonged, Debilitating Illnesses, Rare Diseases, "Gay Cancer", Retroactive Look at HIV's Arrival in the USA, Latency, Not Knowing What Is Happening

Previous Entry - 1076-1980: Storm Clouds on the Horizon

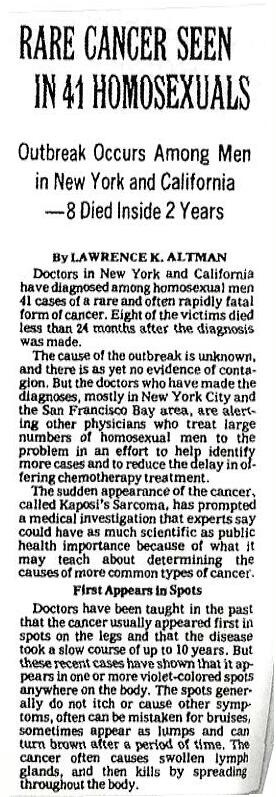

The first news report that appeared in mainstream media in the USA on what would go on to become known as HIV/AIDS1

All animal species have a natural instinct for self-preservation thanks to evolution. Those that never developed this mechanism to a sufficient extinct died out a long, long time ago. It is a vital function that keeps us alive.

Despite humans creating civilizations that worked to diminish some of the rougher and more dangerous aspects of nature, this instinct remains strong in our constitutions for the simple fact that societies are fragile, and threats to our lives can appear immediately. How we choose to assess and then mitigate these threats depends not only on how our societies are organized and what resources we have access to, but also how we personally assess these threats. This will often come down to personality traits that are inherent or are developed over time due to environmental factors and/or personal experiences. Some types select social conformity, others will choose gun ownership, and so on. The examples are endless.

One type of personality known to us all is the ‘Alarmist’. This person will warn others in advance of a threat that they see coming, often exaggerating the actual threat for desired effect. We all know this type, as it has saturated our minds in the age of instantaneous communication and clickbait journalism. A problem with the Alarmist is that they can often be wrong, leading to a “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” reaction from the targeted audience. Excessive alarmism negatively impacts credibility. But for those of you who have been paying attention this past decade, these alarmists actually have a pretty good track record. This is why it pays to not completely discount the paranoid rantings of the ‘internet schizophrenic’.

Larry Kramer (whom we have met earlier in this series) was one of those alarmists. Something in his gut was telling him that the hyper-charged sexual activity of gay men in the 1970s posed an existential risk. He had no way of knowing that the HIV virus was already making its way through the gay community (and IV drug users as well), but he could sense the danger. His 1978 novel “Faggots” sounded the alarm, and Kramer became persona non grata on Fire Island because of it, as he was seen as spoiling the party.2

Some people will react early, others will react too late. Some people will overreact, others will choose to put personal interests above those of the affected community as a whole. Others still will place politics as the primary lens through which to perceive the threat and react to it, pushing down actual public health concerns. Still others will deny that something is happening, with even more others seeing conspiracies unfolding before their eyes. All of the above took place with regards to those first years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Coming Into View

Jed Mattes: It was the first notice that we had of a rare cancer seen among male homosexuals.

Randy Shilts: It wasn’t called AIDS then. It was called GRID.

Damien Martin: A group of men with Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Larry Kramer: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.”

Vito Russo: We were told that Nick died of cat scratch fever, which does not kill you, you know—it was just not possible.

Enno Poersch: He died of AIDS before they knew what AIDS was, you know, when they were all still running around and going, “We don’t understand what this is all about.” He got sick in, uh, ’80 and he died January 15 of ’81.

Vito Russo: We didn’t know then that this was AIDS, but it was AIDS.

Larry Kramer: Even when we found out in ’81, it was much bigger than we thought.

Randy Shilts: I felt so strongly that that would have been a page one story if it had been anybody else getting it.

Larry Kramer: When I saw that in the New York Times, I was scared.

Eric Marcus: Well, if the Times covers it, it has to be real.3

By early 1981, gay men in New York City, Los Angeles, and San Francisco knew that something was wrong. Stories were being passed around the gay communities in those cities about young gay men who were coming down with mysterious and rare illnesses that couldn’t be fought off despite medical textbooks indicating the opposite. Young men were dying when they weren’t supposed to, and no one knew why. All that they knew was that some men were coming down with Pneumocystis Pneumonia (PCP), a lung infection caused by a fungus that is easily fended off by healthy people, while others contracted Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS), a rare cancer causing purplish skin lesions only seen in Mediterranean men over the age of 65 prior to then. It made no sense not just to them, but to the first doctors who saw these patients.

These were very isolated incidents, but they were reason for concern. Depending on the personality type and the social proximity to those directly impacted by these strange illnesses, reactions among gay men varied.

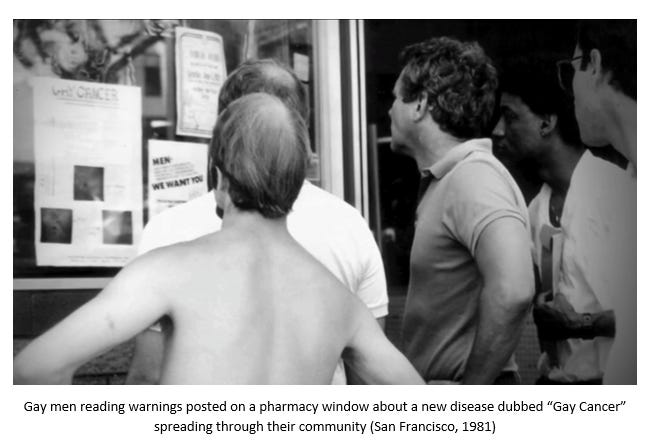

For example, take a look at this clip from the slickly produced 2011 documentary “We Were Here”, and note what the man says beginning at 0:43 about seeing a warning taped to the window of a pharmacy about the strange illnesses going around:

What those men standing in front of the pharmacy window didn’t know (and couldn’t possibly know) was that many of them had already by then unknowingly contracted the HIV virus and were therefore doomed.

The HIV Virus and Latency Period

We first need to take a step back and look at the larger picture to help us understand not just what the HIV virus is, but when it first arrived in North America, and why it managed to find itself a welcoming host in the bodies of gay men and IV drug users (and later on, hemophiliacs).

When the HIV virus was first isolated by Dr. Luc Montagnier and his team at the Pasteur Clinic in Paris, France in 1983, no one knew what the latency period was from the contraction of the virus until the stage then known as “full-blown AIDS”. Accurate testing for the virus was not yet available, and would have to wait another two years. Doctors and researchers were left guessing, while those who had engaged in activities that could expose them to the virus were in a permanent state of panic. Reading through the literature from that time and watching interviews available on YouTube and elsewhere, the general assumption from 1981 to 1984 was that there was a four-year long latency period. This meant that if you abstained from sex, didn’t share needles while injecting drugs, or hadn’t had a blood transfusion in the past four years, you were in the clear.

To their horror, they underestimated the period of time that it took people who contracted HIV to develop full-blown AIDS by several years.