Saturday Commentary and Review #183

Putinism at 25, US Truth and Reconciliation Committee for 2025, The End of the Liberal Era?, Stewart Lee The Little Shit, My Life With Penguins in the Antarctic

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

When Vladimir Putin first walked through those golden doors in an act that signaled the beginning of his presidency, my attitudes towards Russia were very, very different from what they are today. Not only did I inherit a suspicion of all things Russian thanks to my ethnicity, I also was instantly dismissive of Putin because he was a product of the KGB. I had applauded the dissolution of the Soviet Union when it took place, and even supported the Chechens in their first war against Moscow (this was before their fight had become Islamicized). I. like many others, felt that Russia was a dangerous threat to Europe because it had become so weak and desperate, fully expecting that it would lash out in response.

My priors were instantly tested when his leadership won the Second Chechen War by the end of April 2000, four months after he had entered office. This was not the embarrassing, sclerotic, Russian Army of the First Chechen War. “Not bad”, I thought to myself. Putin had defeated an Islamist insurgency, and quite thoroughly too.

Around the same time, Putin publicly met with the seven most powerful oligarchs of Russia at the time, and offered them the famous deal whereby the state would permit them to retain their ill-gotten wealth if they kept out of politics. Of those seven, one immediately fled to Spain, four took the deal, and two decided to challenge Putin, one of them being his former sponsor, Boris Berezovsky. Putin followed through on his threats, forcing Boris to flee into exile in the UK, and arresting Mikhail Khodorkovsky. I was very impressed.

What led me to finally change my mind was Russia’s refusal to join the US-led alliance that invaded Iraq in 2003. Instead, Putin teamed up with Germany’s Gerhard Schroeder and France’s Jacques Chirac to reject participation in a war without justification, one that would only serve to be a disaster for Iraq and the wider region, and that would benefit many dangerous forces, Islamic extremists being one of the main ones. The short period between 9/11 and the US invasion of Iraq was a critical one for my political development, as I immediately saw just how cynically the USA would use 9/11 for its own purposes. Putin’s Russia was fighting Islamic extremism, while the USA was aiding and abetting it. This refusal to go along with Washington plus the examples above are what led me to begin to admire Vladimir Putin.

I am not Russian, I do not want to be Russian, I don’t even want Russia in the EU (it’s far too big and too foreign). However, I cannot but admire the man and his efforts to resurrect Russia from the disastrous Yeltsin era. Any objective analysis of his time in office has to conclude that he has done a very good job with respect to politics, society, economy, and even defense (especially when you factor into it how the USA has been chipping away at Russia the entire time).

Ben Aris reflects on 25 years of Volodya, and he too can’t help but possess a grudging admiration from the man, in his own way:

I went to his very first state of the nation speech where he put demographics at the top of the policy priority list and set the goal of “catching up with Portugal as the top economic priority. Today Russia is the fourth largest economy in the world in adjusted terms, ahead of Germany and recently overhauled Japan as well. Out of the top five biggest economies in the world three are BRICS nations (China, US, India, Russia, Japan).

And he put his money where his mouth is by hiring German Gref, now the head of Sberbank, as an economic guru who launched the “Gref Plan” to implement a radical economic reform plan. It was a heady time. Gref was a total outsider and had no power of his own, yet thanks to Putin’s personal backing he pushed through radical change after radical change that has evolved into today’s National Projects 2.1 that is still a top domestic policy initiative.

The heavy irony is that Putin’s ambition is not to recreate the Soviet Union, but, as he recently laid out in great detail in his Valdai speech, to Make Russia Great Again.

His quote about “the greatest tragedy of the 20th century was the fall of the Soviet Union” is widely abused as the rest of that quote, never mentioned, is “… for Russians who found themselves trapped in “foreign” countries…” ie living in the newly independent 15 republics created in December 1991.

Putin is probably second only to whichever Pope is currently enthroned in St. Peter’s and to Donald Trump in terms of purposeful media misuse of his words.

Early European dreams:

And Europe was up for a partnership with Russia in general and Putin in particular – until Russia started booming in the second decade of this century.

Putin has always seen the best way to make Russia great is through partnership with Europe. Former First Deputy Prime Minister Arkady Dvorkovich told me this personally: “China is too far away, and they are too different from us. Russia is a European country. Our future is with Europe.”

It is also widely forgotten that Putin’s first foreign trip as president was to the UK, where he stood on the floor of the House of Commons and announced a 50:50 joint venture with BP and the privately owned Russian oil company TNK. This was not a 51:49 joint venture, but an unheard of even split 50:50 joint venture – in other words, a true partnership. Tony Blair jumped at the deal and BP made an absolute mint over the next two decades.

Putin then went on to Brussels where he met with Mario Draghi, then head of the EU, and asked to join the EU. He was told “no.” Russia is simply too big and would have swamped the EU institutions. Putin accepted that, so he went on to do the next best thing: he started to build the Eurasian Economic Union (EUU).

I interviewed the architect of the EEU several years later, who told me it was specifically designed to mirror the EU (unlike its precursor, the Customs Union), using exactly the same rule book, so that it could easily integrate with the EU and create a single market “from Lisbon to Vladivostok” - a phrase much loved by Putin for many years.

He even asked to join Nato, which was met with a half measure: the Russia-Nato council.

Much of this is either forgotten, ignored, and hand-waved away, as these overtures to the West complicate the narrative in which Putin is an imperialist bent on domination.

Here’s something new even for me: I was unaware of this failed Opel deal:

But of course, it went wrong most obviously from the 2014 annexation of the Crimea. In the run up to the annexation, the EU blocked many of Russia’s attempts to create other partnerships like BP-TNK that Putin pursued, like buying shares in EADS (Airbus) in an attempt to get a seat on board to rescue Aeroflot and Russia’s aviation industry, or its attempt to buy the bankrupt Opel carmaker to rescue AvtoVaz. That deal was blocked by the US to prevent the technology transfer to Russia that would have created a European automotive powerhouse. Putin, who had personally brokered the Opel deal with former German Chancellor Angela Merkel, was visibly furious when Washington put the kybosh on it. And that is not to mention Russia’s 18-year-long WTO accession saga that finally ended in 2012 – probably the high water mark in East-West relations, when the long-sought “partnership” looked like it might work. Russia made a lot of significant concessions to get into the WTO, like basically sacrificing its entire pork production business to European imports.

Disillusionment:

Putin became disillusioned as it became clearer and clearer that the EU would never accept Russia as a partner. The Maidan revolution in Ukraine in 2014 crystalised these fears. Putin came to the conclusion that the West was actively afraid of Russia’s competition in things like aviation and automotive and actively trying to hobble Russia’s development, but at the same time the EU was happily helping itself to Russia’s cornucopia of raw materials and giant consumer market, the largest in Europe.

These tensions came to a head when EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell came to Moscow in 2021 to broker a deal and repair relations with an increasingly brittle Kremlin. He suggested trade should be separated from politics – a compromise. But it was too late. Borrell was met by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov who humiliated the EU diplomat by having three EU diplomats expelled while the two men were sitting across the table from each other and then followed up with the “new rules of the game” speech delivered in February 2021 at a joint press conference. Lavrov’s main point was: Russia would no longer tolerate the West doing business with one hand and applying sanctions and interfering with Russian domestic policy with the other. With this speech, Putin’s patience with the West had run out and the speech was the first shot fired in what would become the Ukraine war a year later.

Putin’s dream of a single market from Lisbon to Vladivostok was dead. Putin never wanted to partner with China – Russians remain as afraid of China as the West is – but given the failure of building a European partnership, the Chinese option is the obvious alternative. By rejecting Putin’s overtures to build real working relations and engaging with Russia, albeit a difficult and daunting prospect, the upshot has been to drive Moscow into Beijing’s arms, which I suspect will prove to be a major geopolitical blunder in the long-term.

Economic revival:

The Western-advocated “shock theory” introduced by Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar inflicted almost a decade of misery and an early grave for tens of millions of men. I arrived in Russia in 1993 just after the price liberations were put in place and inflation was running at 1,400% a year – 4% a day. The economic crash was an order of magnitude worse than anywhere else in the former Warsaw Bloc, as detailed by bne IntelliNews’ despair index, and the payment system collapsed so completely that Russia became a barter economy as its money became meaningless – the so-called virtual economy, made famous by academics Barry Ickes and Clifford Gaddy – again something that is rarely mentioned these days.

Putin quickly fixed all these problems, starting with a complete overhaul of the labour code that slashed Soviet bureaucracy and the introduction of a flat tax regime that unfettered business. The tax rates – the lowest in Europe – have remained untouched for almost all of Putin’s tenure. It has only just been amended in the last few months to finally introduce the beginnings of progressive taxes 25 years later.

The effects of these reforms were stunning. Russia was still reeling from the default and devaluation on August 13, 1998 when Putin took over at the start of 2000. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was predicting that Russia’s economy would spend years in recession at the time; GDP expanded by 10% that year in a record that has never been matched. That marked the start of a totally unexpected decade-long boom that transformed everyone’s lives.

“At the time the average per capita income in the US was $30,000. If you took that as the baseline for the equivalent incomes in Russia in 2000, then by 2008 the equivalent per capita incomes in Russia were $600,000 a year,” a Russian friend explained to me to describe what the change felt like.

Western critics of Putin fail to judge him by Russian standards, instead insisting on measuring him by their own standards, ones that are completely foreign to Russia and Russians. This goes a long way in explaining why so many of them fail to grasp his popularity, and the refusal on the part of Russians to risk liberalization, as they fear it could lead to a return to the disastrous 90s.

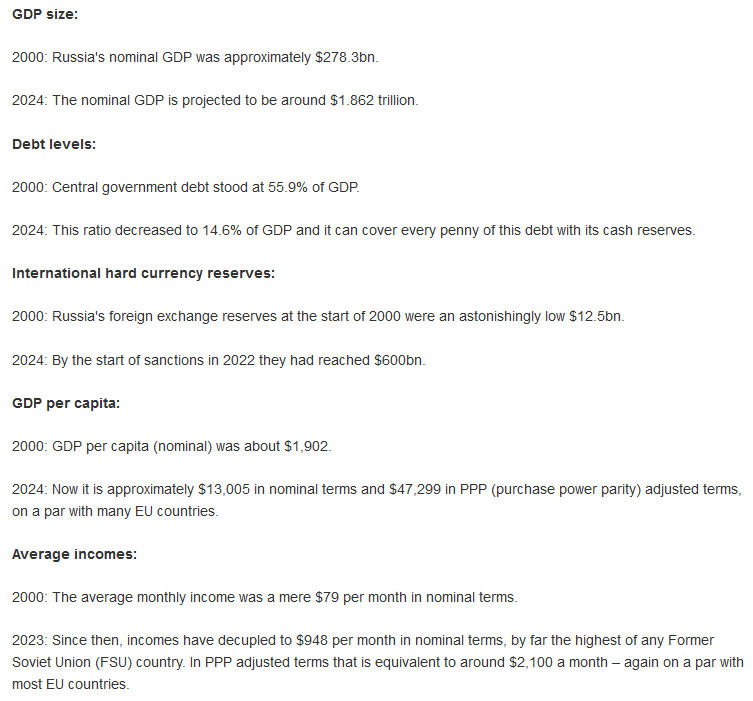

Aris argues that the economic transformation is the basis of Putin’s popularity, and I can’t help but agree. Here are some numbers:

Restoring sovereignty and national pride:

Moreover, Putin's job of making sure there is no alternative has been made easier by the fact that the opposition has remained fissiparous and ineffective. The two opposition politicians that might have replaced Putin – Boris Nemtsov and Alexey Navalny – were both murdered. But even if they had been allowed to run for office, most Russians see both as untested and unqualified to run the country. The irony of Russian elections is Putin would probably still win even if they were free and fair. When criticised by a reporter as Putin took office for the fourth time, he shot back: “And how many terms has Merkel served? Four, isn’t it?” She had just been re-elected for a fourth time two months earlier.

As for the Ukrainian war, Russian surveys conducted in 2022 universally found that Russians thought that going to war with their “brothers” in Ukraine was a stupid idea and were very uncomfortable with the idea of Russian troops invading Ukraine. However, since then similar surveys have found that once the war started, and as it is universally seen as a war with Nato, which is supplying most of Ukraine’s weapons and half its money, Russia needs to win.

That is another thing that Putin gifted Russia with: the restoration of the famous Russian national pride after the humiliation of losing its superpower status following Yeltsin’s dissolution of the Soviet Union – another reason why Yeltsin is so hated in modern Russia. Today patriotism is at an all-time high.

It obviously hasn’t been all wins for Russia over the course of the past quarter-century, but by an objective analysis one must conclude that Vladimir Putin has done one hell of a job turning his country around.

We’re only days away from the Inauguration and everybody is waiting to see if Trump has learned anything from his first go at being President of the United States of America.

Despite having his first termed sabotaged by all the forces arrayed against him, optimism remains high that he indeed did learn something last time, and that he will be able to implement at least some of the agenda items that propelled him into office. Curiously, the opposition this time around appears to be rather muted, especially when compared to 2017. Did they exhaust themselves? Or have they entered acceptance mode? Time will tell.

The expectations for Trump47 are plenty, and here are a few of the key ones:

immigration reform/mass deportation of illegals

de-regulation to permit certain business sectors to “let rip”

a peace deal to end the fighting in Ukraine

a more transactional approach to foreign policy

These are just four examples, but there is another one that I wish to highlight: the desire for a certain amount of revenge against the previous regime and the establishment overall. Some Trump supporters want vengeance, and expect it as well. Whether it be for lawfare, for discrimination due to “Wokeness”, etc., the desire for settling scores among #MAGA supporters is not be underestimated.

More sober minds would be content with just the truth of what has gone on all these years, one of these minds being Peter Thiel:

In 2016, President Barack Obama told his staff that Donald Trump’s election victory was “not the apocalypse”. By any definition, he was correct. But understood in the original sense of the Greek word apokálypsis, meaning “unveiling”, Obama could not give the same reassurance in 2025. Trump’s return to the White House augurs the apokálypsis of the ancien regime’s secrets. The new administration’s revelations need not justify vengeance — reconstruction can go hand in hand with reconciliation. But for reconciliation to take place, there must first be truth.

The apokálypsis is the most peaceful means of resolving the old guard’s war on the internet, a war the internet won. My friend and colleague Eric Weinstein calls the pre-internet custodians of secrets the Distributed Idea Suppression Complex (DISC) — the media organisations, bureaucracies, universities and government-funded NGOs that traditionally delimited public conversation. In hindsight, the internet had already begun our liberation from the DISC prison upon the prison death of financier and child sex offender Jeffrey Epstein in 2019. Almost half of Americans polled that year mistrusted the official story that he died by suicide, suggesting that DISC had lost total control of the narrative.

The Ancien Regime vs. The Internet is an interesting framing. It reminds me of a Mexican-American guy from California who I knew years ago and who summed up Trump’s 2016 shock victory as “the revolt of the newspaper comments section”.

We cannot wait six decades, however, to end the lockdown on a free discussion about Covid-19. In subpoenaed emails from Anthony Fauci’s senior adviser David Morens, we learnt that National Institutes of Health apparatchiks hid their correspondence from Freedom of Information Act scrutiny. “Nothing,” wrote Boccaccio in his medieval plague epic The Decameron, “is so indecent that it cannot be said to another person if the proper words are used to convey it.”

In that spirit, Morens and former chief US medical adviser Fauci will have the chance to share some indecent facts about our own recent plague. Did they suspect that Covid spawned from US taxpayer-funded research, or an adjacent Chinese military programme? Why did we fund the work of EcoHealth Alliance, which sent researchers into remote Chinese caves to extract novel coronaviruses? Is “gain of function” research a byword for a bioweapons programme? And how did our government stop the spread of such questions on social media?

Now that the dust has settled, I think that it is safe to conclude that nothing in recent memory has radicalized so many “normies” as what western governments put their own citizens through during the COVID era. I can’t recall anything that has made so many non-political or politically apathetic people turn very political.

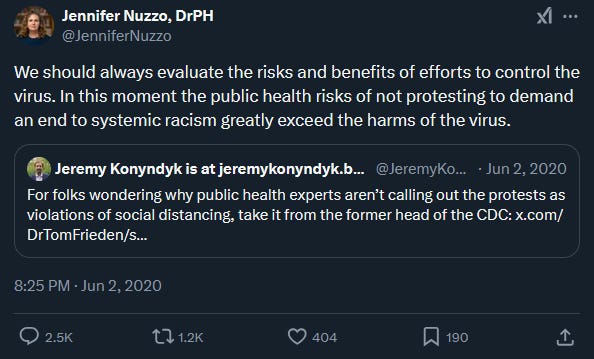

Personally, I will never, ever forget this:

This next excerpt is very interesting because I am certain that many of you share the same suspicions that I share with Peter Thiel:

Our First Amendment frames the rules of engagement for domestic fights over free speech, but the global reach of the internet tempts its adversaries into a global war. Can we believe that a Brazilian judge banned X without American backing, in a tragicomic perversion of the Monroe Doctrine? Were we complicit in Australia’s recent legislation requiring age verification for social media users, the beginning of the end of internet anonymity? Did we muster up even two minutes’ criticism of the UK, which has arrested hundreds of people a year for online speech triggering, among other things, “annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety”? We may expect no better from Orwellian dictatorships in East Asia and Eurasia, but we must support a free internet in Oceania.

In light of the Twitter Files, I certainly cannot exclude the possibility that US diplomacy played a hand in the Brazilian affair. After all, the Americans do have a long history of laundering foreign policy via willing partners (rendition, the Steele Dossier, torture in Syria, etc.).

More:

Darker questions still emerge in these dusky final weeks of our interregnum. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen recently suggested on Joe Rogan’s podcast that the Biden administration debanked crypto entrepreneurs. How closely does our financial system resemble a social credit system? Were an IRS contractor’s illegal leaks of Trump’s tax records anomalous, or should Americans assume their right to financial privacy hinges on their politics? And can one speak of a right to privacy at all when Congress conserves Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, under which the FBI conducts tens of thousands of warrantless searches of Americans’ communications?

What Thiel is proposing is for the ancien regime to come clean in order to clean the slate and begin anew:

South Africa confronted its apartheid history with a formal commission, but answering the questions above with piecemeal declassifications would befit both Trump’s chaotic style and our internet world, which processes and propagates short packets of information. The first Trump administration shied away from declassifications because it still believed in the rightwing deep state of an Oliver Stone movie. This belief has faded.

Our ancien regime, like the aristocracy of pre-revolutionary France, thought the party would never end. 2016 shook their historicist faith in the arc of the moral universe but by 2020 they hoped to write Trump off as an aberration. In retrospect, 2020 was the aberration, the rearguard action of a struggling regime and its struldbrugg ruler. There will be no reactionary restoration of the pre-internet past.

The future demands fresh and strange ideas. New ideas might have saved the old regime, which barely acknowledged, let alone answered, our deepest questions — the causes of the 50-year slowdown in scientific and technological progress in the US, the racket of crescendoing real estate prices, and the explosion of public debt.

Perhaps an exceptional country could have continued to ignore such questions, but as Trump understood in 2016, America is not an exceptional country. It is no longer even a great one.

Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg, and many others have followed Thiel’s lead in rejecting the Democrats and their vision for America. During the first Trump term, Big Tech was bullied by establishment and media into doing quite a lot of the dirty work for them, with social media censorship being the most obvious example. This time around, Big Tech is firmly in Trump’s corner. These are all self-interested parties, so proceed in caution and don’t give them the benefit of the doubt. Make them earn your trust.

It is my contention that all of us who live in the West are “default liberals”, with certain differences between groupings that fall within the larger liberal framework. This is the result of having our post-war order built upon the defeat of Nazi Germany+the collapse of the Soviet Union, with the USA as the leading power.

It is very difficult to imagine any of our countries turning against liberalism in real terms towards actual authoritarianism, even if the USA would permit such an experiment to take place. Elections, political parties, open debate (for the most part), etc., all seem so natural to us. We would be like fish out of water if any of these necessary elements of liberalism were denied to us. The emphasis on individual human rights in our constitutions and laws only cements its assumed permanence in our minds. On the other hand, never say “never”.

Personally, I think that the reports of the death of liberalism are greatly exaggerated, to paraphrase Twain’s famous line. All parties in the West with any popularity or representation in their respective legislative assemblies fall within the liberal democratic framework, despite what loud voices in media, politics, and culture will have you believe. Trump is a 90s Clinton Democrat, and his cabinet is shaping up to be a coalition between conservatives (liberals) and disaffected liberals (also liberals). Germany’s AfD is not the NSDAP, nor is it even “far right”. These populists are all liberals to one degree or another, and they are all seeking to trim back some of the recent excesses of a more exuberant liberalism that veered off course into semi-authoritarianism aka “illiberalism”.

Aris Roussinos is of a different opinion than mine (which is why I will yell at him on the phone later this evening):

This year’s surrender of the crown has proved smoother than the contested handovers of 2016 and 2020: this time, neither side has summoned up their mobs. Broken, dejected, for the first time self-doubting, America’s liberal establishment has come to accept the extinction of its political order. Had they taken their project — or their right to eternal rule — as seriously as they claimed to, no doubt they would have chosen stronger candidates than Joe Biden and Kamala Harris: that they could not do so itself speaks of a certain exhaustion. Beyond the rhetoric, at least as messianic and civilisational in scope as anything the further reaches of the Right could dream up, Left-liberalism — the last of the great 20th-century ideologies — possessed very little of substance to fight for. Bereft of ideas and confidence, American liberalism died from the head down: all that is left of it is an entrenched caste of bureaucrats to be weeded out and replaced. The old order is dead: but what is struggling to be born?

Aris is correct in describing the outgoing regime as having exhausted itself, no longer able to muster up the energy to do in 2025 what it did from 2017 to 2021. Yet I think that his definition (in this case) of liberalism is far too narrow. The incoming regime largely wants a return to the liberalism of the pre-Obama era. This is not a revolution.

For a time, in the 2010s, confused and frightened liberals cycled through a series of personality cults, latching onto populist avatars of its own — Trudeau, Merkel, Ardern, Macron – who promised, like King Arthur against the invading Saxons, to hold back the waves of history for a time at least. Yet all of these are now politically dead, having achieved little but accelerating the incoming power of the waves that would wash them away: in Macron’s case, characteristically the most interesting, seemingly by design. No doubt, this cult of personality took root due to the absence of serious policy: it is an obvious fact of our present political moment that anyone concerned with shaping the world they actually live in can only now engage with “the Right,” simply because “the Left” is both intellectually and politically defunct. We see this in the intellectual Left’s new engagement, part fearful but increasingly curious in its own right, with the ferment of ideas on the Right. What is the Left’s project, what are its big ideas now it has broken its political and intellectual power through its catastrophic self-derailment into identity politics? It is a difficult question to answer, but also a pointless one: it simply doesn’t matter, and is unlikely to for the next few decades at least. One might as well ask what is next for Baathism.

My view is different than Aris’ here: this liberal faction overplayed its hand, and now has to retrench for a bit….but its gains are undeniable, with most almost certainly impossible to rollback (think “gay marriage”). These victories are being consolidated despite their electoral loss.

Yet even still, “the Right” is, conceptually, an absolute mess. Much of what is novel in it is genuinely harmful, and presents huge risks of even worse political futures than those given to us by millenarian Liberalism. As Yeats saw it at a similar time of political flux, “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.” If it possesses any coherent, unifying purpose, the new Right consists merely of rolling back the liberal innovations of the Sixties onwards: and perhaps that is progress enough. Much of Trump’s initial appeal was that of the boy in the Emperor’s New Clothes, mockingly pointing out the nakedness of the West’s rulers. Had they taken the critique seriously — of their radical identity politics of race and gender, of their programme of economic self-destruction through a unilateral energy transition, of their commitment to an imaginary borderless Utopia in which the rest of the world dreams only of achieving its historic destiny as Western liberals — perhaps the destruction of their order would not be so total. The dying liberal order chose suicide through want not just of self-reflection but of pragmatism. And indeed, perhaps if the incoming order has a single defining characteristic, it is pragmatism rather than any coherent replacement ideology. Perhaps it is not just the great 20th century ideologies — fascism, communism, postwar liberalism — that are dead, but any all-consuming ideology at all.

Aris correctly points out that much of what has led to the rejection of the Democrats (and to left-liberals elsewhere) lacks real coherency and vision, which bodes ill for the future of these new rejectionist regimes. Owning the libs is not policy, nor is it even remotely close to good governance.

The 20th century liberal democratic model is going the same way as the great 20th century totalitarianisms it defined itself against. Yet — as reflected in liberal discourse where the assumption made is that politics is a binary choice between liberalism and fascism — liberals are still trapped in the 20th century, fighting ghosts, even as the world has already moved on. Applied to the international order, then, the conclusion — we must hope — of the war in Syria is a perfect example of this conceptual shift. Just a few years ago, the operating assumption that a stable conclusion to the Syrian war was really something within the West’s (which means America’s) power to bring. Instead, we have witnessed the opposite: rebel victory was brought by a group the West shuns, under US terror sanctions for perfectly valid reasons. The West’s purported end state in Syria, a rebel victory, was brought about by the West walking away from the problem, and conceding strategic defeat. Yet the relatively bloodless form of political transition witnessed in the past few weeks was also brought by the seeming strategic victors — the supposed resistance axis of Iran, Russia and Hezbollah — making the pragmatic decision to withdraw support from Assad, confident that they could maintain their interests in the new order.

I reject this assessment as I cannot countenance the notion that the Americans had nothing to do with the recent HTS victory in Syria. Turkey did much of the heavy lifting, but it was the sanctions regime alongside the distraction of Iran and Hezbollah that permitted the very weak Ba’athist government to collapse in on itself so rapidly. This, to me at least, signals a big victory for the Americans, and for their system. It’s clearly an embarrassment to the Russians, and a significant loss for Iran, both of whom are revisionist powers.

Aris has much more to say about his contention that liberalism is on the ropes than I have shared with you here, so click this link to read it in its entirety.

British comic Stewart Lee is by far my favourite standup comedian these days. He has a flair for the absurd and a style that I really, really enjoy. His politics are 180 degrees from mine, a fact that doesn’t bother me when I watch one of his performances.

“Stu” is a very, very politically correct person, and proud as hell to be one. He calls it “being empathetic”, as many of them tend to do. And he is correct when he points out just how idiotic, boorish, and predictable many “anti-woke” types tend to be. Despite this, there is room for criticism of Stu, something that

is more than willing to deliver:It would be convenient for me, as the author of a critical piece about the comedian Stewart Lee, to say that he isn’t funny. It would be convenient for Stewart Lee, as the subject of a piece in The Critic, to be described as being unfunny. Unfortunately for both of us, Stewart Lee is very funny — one of the few great stand-up comedians of our time.

One of his funnier qualities has been his disdain for many of his peers. His unfavourable comparison of Ben Elton to Osama bin Laden, a man who “has at least lived his life according to a consistent set of ethical principles”, is a classic. His contempt for the work of Russell Howard — “observational comedy from a Victorian mental hospital” — is glorious.

On “Anti-Woke” comedians:

Another of Lee’s targets is “anti-woke” comedy. Frankly, he makes some good points. A lot of “anti-woke” comedy, as I’ve written before, is absolute trash — revelling in its supposed provocative status without being funny. Jerry Seinfeld complained about “P.C. crap” in comedy this year while writing and starring in Unfrosted — a film that was about as funny as footage from 9/11.

But Lee goes too far. He’s right that some comedians who complain about political correctness “are filling stadiums, winning Grammys, and getting $60m off Netflix”. But that wouldn’t be the case if people on his side of the political aisle had succeeded in having them censored. Dave Chappelle might not have been “cancelled” for his jokes about transgenderism but Netflix employees certainly tried. If I’m convicted of attempted murder, I can’t say, “But he’s alive, isn’t he?” (Other cancellations have been more effective, such as the long exile of Graham Linehan.)

“If [Jerry Seinfeld]’s not able to think a little bit around whatever he imagines are these current restrictions are[sic],” Lee tells Prospect, “then he’s not a very good comedian. It’s pathetic and ungrateful and unimaginative.” Some might recall the time when Lee faced protests against Jerry Springer: The Opera, a musical he co-wrote that some Christians considered blasphemous. I remember Mr Lee complaining, and rightly so, about these protests, and I doubt that he looks back and thinks he was being “pathetic and ungrateful and unimaginative” and should have thought a little bit around the protestors’ “restrictions”. If the difference is that he agrees with “these current restrictions”, he should say so.

He won’t, though.

But Lee has had a long record of being unsympathetic to satirists who have faced censoriousness if they happen to disagree with him politically. When he was facing protests against Jerry Springer: The Opera, he rankled at comparisons between himself and the cartoonists who were facing death threats for drawing Muhammad. The comparisons were flawed, yes, but Lee was not objecting for the obvious reason that he, unlike Lars Vilks and Kurt Westergaard, was not facing serious threats against his life. He wrote:

In my new capacity as sin-eater for the religious guilt of the entire world, I fulfil a lifetime’s ambition by appearing on the Today programme, with a member of the Muslim Council to discuss the Danish Mohammed cartoon controversy. Everyone’s anxious to draw parallels with the opera’s persecution by the Christian right, but the Danish cartoonists wandered into a world of protected religious symbols they didn’t understand. We have used a set of icons whose implications we appreciate, within a tradition of Christian imagery.

This read an awful lot like Lee was saying that because Muslims have more of a theological basis for being sensitive about their religious iconography, if some of them respond with violent censoriousness to offence, it’s the fault of the people who have caused offence. They should have known that people would try to murder them.

More generously, Lee might have been trying to rationalise his sense that Muslims have been excluded enough without comedians making fun of them and their religion. That’s debatable — but what’s not debatable is that people who have made fun of Islam are a more excluded group, because they have a lot of people trying to exclude them from the realms of the living. I’m sure it was annoying for Lee to have his shows cancelled but it wasn’t as dramatic as Kurt Westergaard hiding with his granddaughter in a panic room while an axe-wielding maniac tried to kill them, still less the staff of Charlie Hebdo being shot to death.

If you DO want some laughs this weekend, check out one of Stu’s many standup performances that can be found online. He is both hilariously funny and an ass.

We end this weekend’s SCR with a look at how living alongside penguins in the Antarctic is really like:

I was working at an ecosystem monitoring camp called Cape Shirreff, in Antarctica, where we collected data on the seals and penguins that breed on the island and hunt krill in the waters nearby. The long-term monitoring program was initiated to measure the impact of the krill fishery, but climate change has become a key focus of the research.

The five months I spent at Cape Shirreff dovetailed with the summer breeding season of our target species: chinstrap penguins, gentoo penguins, and Antarctic fur seals. Most of the methods we used were standard ecosystem-monitoring protocols developed by a committee under the Antarctic Treaty that focuses on the Southern Ocean. To monitor the penguins, we’d be documenting nest counts, adult survival, adult weight, egg weight, egg lay dates, chick hatch dates, chick growth rates, chick survival, and the composition of penguin diets. We’d attach data loggers to penguins to measure the duration of their foraging trips, how deep they had to dive to find food, and where they found it.

In the early season we waited for the nests to take shape and eggs to be laid. Once a nest was confirmed active, when eggs appeared, I banded one bird at each of the 75 plot nests I was tracking so I could discern between individuals. It was easiest to do this when the penguins were incubating because they didn’t run away. At the beginning of the banding period, Matt took me out to his colonies so he could teach me how to handle and band the birds. As gentoos had started laying first, we started with them.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

And please don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already!

Great SCR. However, you left out a few salient facts about Putin. The US had effective control over Russia under Yeltsin. The US had a patron/client relationship with the oligarchs and Washington did everything it could to plunder Russia and wreck it in the process. The results were a form of systemic dysfunction and depraved indifference to human suffering. Putin's entire political project has been to repair the damage of the Yeltsin era and to counter Wsshington's influence within the territories of the former USSR.

Putin's success in getting Russia back on its feet has earned him enormous respect overseas, especially in Asia. Serious political players across the world think highly of him. The contrast with the growing contempt for the Atlanticist political class could hardly be greater.

Europe's inability to work with Putin demonstrates how truly worthless the EU truly is. Brussels was offered opportunities that could have underpinned European prosperity for generations to come. Yet the Euros threw away those opportunities. Xenophobia and Russophobia played a part, as did the servility of the EU to Washington and the defining mediocrity and senselessness of the European political class.