Saturday Commentary and Review #110

Russia Behind the Front-Line, Poland in the Crosshairs, "Anti-Semitic" Zionists, Resource Nationalism, English Romanticism as "Germanomania"

Everyone is now waiting for the coming Russian offensive in Ukraine, one that is being manned by the call up of 300 thousand conscripts, 70 thousand new volunteers, and additional existing forces from elsewhere. Where will they attack from? What will be their targets? We don’t know.

What we do know is that Igor Girkin was proven correct in that the original forays into Ukraine were undermanned. This call up of men that began last Autumn is testament to that. As of now, the Russians have only secured a land bridge to Crimea via Southern Zaporizhzhia and the southern half of Kherson. They have also been grinding down Ukrainian forces that keep being thrown at them, while belatedly beginning to target the energy grid throughout Ukraine. The gloves are not yet off, but they are being tugged at in that direction.

The lack of the Russian knock out punch has left many to conclude that Moscow has failed in its objectives, despite the fact that the war has not ended. We are used to instantaneous results these days, we people of little patience. One of the great surprises of this war is just how patient the Russians have been.

The Ukrainians are fighting and are being ground down. At the same time, they are correctly using wartime to further distance themselves from Russia culturally, historically, confessionally, and so on. The inevitable historical process that is the removal of a state from its previous ruler’s orbit is almost complete. War is the best way to strengthen and reinforce a national identity, as it is the most cataclysmic of all events that it can face.

We are bombarded daily with puff pieces about the “Churchillian” Zelensky, and about how the Ukrainians are “bravely” facing down Putin (I will never criticize them for fighting for their homeland, btw), but we are not given a fair peek as to what is happening within Russia. Western media continues to hope that anti-war protests break out, that the state is destabilized, that terrorism is unleashed, and that Putin is removed from power, non-violently, or violently. Gilbert Doctorow has presented us with his pro-Russian view as to what is happening in wartime Russia, which I will now excerpt from. Treat it like you would any western opinion; with a grain of salt:

The consolidation of Russian society is a much discussed topic these days on Russian talk shows. One dimension of this has been the political cleansing, the voluntary departure or removal of the 1990s vintage West-loving Liberals who, to a large degree, despised their fellow citizens and, whenever possible, spent their free time in Europe or the States.

One of the leading voluntary exiles who left the country just ahead of warrants to appear in court to face corruption charges was Anatoly Chubais, who had built his fame or infamy in the 1990s as a director of the privatization programs that helped to create the circle of so-called oligarchs that dominated Russian political life until they were tamed, imprisoned or expelled by President Putin early in the new millennium. There were, of course, hundreds and thousands of lesser devils who have been a counterweight to the forces of patriotism through the entire Putin presidency.

Those of you who have been reading my Substack for some time will know who Anatoly Chubais is (just use the search function here if you don’t).

Western media will present these exiles as “the best of the best”, indicating a brain drain. There might be some truth to that, but what truth there is to it is rather exaggerated. Russia does not lack for brains.

In past essays, I mentioned the phenomenon of volunteer work across the Russian Federation to solicit and collect contributions in money and kind to support the Russian soldiers in the field. I spoke about the letters to the soldiers from school children, about the food and clothing sent to the front by newly formed local NGOs. I add to this the phenomenon of volunteering to fight that is remarkable in scope and in who is coming forward. These include Duma members, administrators and legislators from oblasts reaching across European Russia, across Siberia to Kamchatka and the Far East. These volunteers receive military training in specialized units, among them one named “Akhmat” in honor of the father the Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov and under his direct supervision.

Time spent in the Donbas by Russian volunteers, even those not directly engaged in battle, is not risk free. We all learned a week ago of the nearly fatal injuries sustained by Dmitry Rogozin, one-time RF Ambassador to NATO here in Brussels and for a number of years the head of Roskosmos. We do not know what tasks he was performing in Donbas as a volunteer, but we do know that he was caught in an artillery barrage and that he had to undergo an operation to remove metal fragments from the vertebrae of his neck.

Morale is high, and notable people have skin in the game as we can see here:

Meanwhile, Russian cities, led by Moscow and St Petersburg, have made collective contributions of manpower to assist the war effort, something you will not read about in The Financial Times. In the time since the September mobilization, while the proper conditions for a major offensive against the Ukrainian army are not yet met, the Russians have been busy doing groundwork to ensure that there will be no further Ukrainian breakthroughs along the 1,000 km front such as happened in Kharkov oblast in the late spring. They have dug in and created second and third lines of defense consisting of well executed trenches and pillboxes. And who did much of this? It was done by the 20,000 municipal workers sent down to the Donbas by Mayor Sobyanin of Moscow and an additional 10,000 civilian workers sent by Petersburg.

Russia’s best performance thus far has been its economy, shocking everyone:

The policy of import substitution has turned into a broad program of reindustrialization. Success stories are featured daily on the news.

The government is giving cheap credits to manufacturing start-ups to provide encouragement. With new, high paying positions being created, it is no wonder that the Russian unemployment rate has moved down close to 3%. That all by itself favors confidence and pride in society.

and

But there are also other changes in Russia coming out of this war that are driven by the US-led sanctions. The forced abandonment of Europe as its largest economic partner has compelled Russia to expand ties with China, with India, with the Global South. This is grudgingly getting some attention in The Financial Times and other Western media, which have reported on the new infrastructure being built and being planned to increase energy exports to China and India, for example. A week ago, a gas field in Eastern Siberia using a newly completed 800 km long pipeline is now feeding directly into the Power of Siberia main pipeline to China.

There is even mention in our media of the astonishing cooperation developing between Russia and Iran to realize a North-South logistics project that was first planned in the year 2000 but never found practical application. Today this multi-modal rail, river and sea corridor stretching from St Petersburg in the north to Mumbai in the south and traversing Iran is showing impressive first deliveries of grain cargos and holds the promise of changing supply chains in Eurasia in a cardinal manner, sharply reducing transit times and costs.

The final excerpt highlights what I wrote back in February of last year, the day before Russia invaded Ukraine: how Russia is now finally done with the West (an American victory, btw):

The other side of the same coin is growing contempt for Europe and the Collective West. Russian news is providing accurate, not propagandistic coverage of the energy crisis, rampant inflation and anxiety of European populations. This, in combination with the acts of vandalism and destruction perpetrated against Russian war monuments in the Eastern states of the EU, in combination with other manifestations of Russophobia in Europe in the cultural and tourism domains, has turned even the hitherto Western leaning Russian intelligentsia into patriots by necessity.

Russia is consolidating and shifting to the East. This is a win for the USA, but a loss for Europe as it is now wholly reliant on the Americans not just for defense, but for energy too. Previously it could not put all of its eggs in one basket. That is no longer the case. As for Ukraine, they now have to brace for the second impact.

“No good deed goes unpunished”, as the saying goes.

The Poles are about to learn this lesson, and learn it hard. Being the northern rampart of NATO and Europe on the mainland continent, they have gone above and beyond in their support not just of Ukraine’s military defense against Russia, but also in opening up their own border to house millions upon millions of Ukrainian refugees. You would think that by doing more than what could be possibly asked of them would grant them grace from the liberal elites in Brussels and Washington, but you would think wrongly to do so.

Poland’s government is too retrograde for this 21st century western world. In too close of an embrace with the Catholic Church and too socially conservative when it comes to “rights” (in the secular, liberal sense), its government is openly targeted for soft regime change much like Hungary has been for the past decade or so. Poland’s current leadership is well aware of this, and is reacting to it as best as it can. But it has few friends in its fight on two fronts:

Poland’s political elites used to believe that it was in the country’s interest to be more greatly integrated with the European community to limit the power of the major European players. However, since 2011, when the European Parliament attacked the new constitution introduced in Hungary and demanded that it be changed, this belief has waned.

The dispute with Budapest was over Hungary’s insistence on enshrining conservative Christian values in the country’s main legal document, while the European Parliament wanted Hungary to move toward secularism and progressivism. In order to enforce a political union, European institutions began to attempt to enforce ideological unity.

The pressure on Poland began in the autumn of 2015 when the new conservative government refused to participate in the scheme for the compulsory relocation of refugees. There was also disagreement over climate policy, as Poland had doubts about its goals.

Brussels showed its hand in its treatment of both Warsaw and Budapest regarding migrants. The dictatorial approach was much harsher in tone than anything that preceded it. This conflict has served as the backdrop for all that has transpired since between Brussels and these two EU member states, despite what official stances suggest.

Nation-state as better in handling crises than the EU:

Since then, a number of crises have gripped the EU and exposed the illusory nature of European integration.

The first of these was the pandemic in 2020. It quickly became apparent that only the traditional nation-state had the organization and public services to be able to handle such an extraordinary situation.

The second crisis that followed was the Russian assault on Ukraine, which showed how European economies had become dependent on those of enemy states. This became apparent when Russia cut off gas and oil supplies, sparking major disturbance in European markets. The ensuing energy crisis was caused by mistakes made by key EU member states, leaving the EU passive and marginalized.

In the case of both the pandemic and the war, EU institutions had little or no say in terms of finding solutions.

The EU now has a mechanism to hold member states hostage:

Let’s take the way the European Commission has led the way on the European recovery fund and the fact that member states agreed to underwrite common debt. This is a revolutionary step on the way to the EU becoming a superstate. As a result of this common debt, the European Commission has obtained an instrument to force member states’ hands on a slew of policy areas. In reality, it can dictate laws, make executive decisions, influence court verdicts, and even make the final decision on the makeup of governments.

The milestones set by the European Commission in the dispute between the EU and Poland on rule-of-law compliance is a classic example of this. In order to get its share of the EU recovery fund, Poland is being forced to change its policies in areas that up until now were not areas of competence for the EC as envisaged by the Treaties.

As Machiavelli observed, it is the pursuit of hegemony, rather than any declared political goals, that is the driving force of history and politics.

That hegemony is to be one of the EU institutions over the member states.

Only through the formation of a bloc of states to challenge these moves by Brussels can member states ensure that what remains of their sovereignty is not eroded further.

It’s impossible to please everyone all the time, and it’s often the case that being very supportive of someone or something will only lead to suspicion as to your perceived ‘actual intentions’.

Jewish history is full of persecution at the hands of others, which makes some of them very, very paranoid of non-Jews when they opine on the subject of Jews (somewhat justifiably). Case in point: there was a magazine called ‘Jewcy’ that had a brief run around a decade ago. I only recall one article from it: a piece in which a micro-fashion in Berlin that saw young men wear styles influenced by Hasidic males denounced as “anti-semitic” because it was “too philosemitic”. I can’t recall the stated logic behind this charge, but I found it funny and it has stayed with me ever since as an example of being excessively sensitive and far too worried about their present condition.

What sparked my memory was this essay by Peter Beinart in which he argues that some Zionists are anti-semitic. Beinart has embraced liberal democracy as the “one, true faith”, and insists that it too be applied to Israel, a state designed specifically for his fellow Jews. To him, secular liberalism is the default state, so therefore any non-Jew to the right of that is automatically anti-semitic when dealing with Jews:

For conservatives like Klein, the relationship is clear: Zionism and antisemitism are incompatible. The former precludes the latter. For liberals like Chotiner, by contrast, the relationship is obscure. “For whatever reason,” Trump loves Israel but derides American Jews. When faced with the coexistence of Zionism and antisemitism, liberals and centrists tend to describe the two beliefs as either unrelated or in tension. In October, an MSNBC commentator tried to reconcile Trump’s antisemitism and his Zionism by suggesting that he “didn’t necessarily understand his own policies” toward the Jewish state. A Politico essay in December described the Christian right’s support for Israel and distrust of American Jews as ideological “contradictions.”

Beinart starts the essay off with bullshit: Trump has been critical of American Jews as a group because they overwhelmingly vote Democrat, not because they are Jews. This is incredibly lazy of Beinart, but it’s par for the course for him.

Check this out:

Trump’s fondness for Israel and antagonism toward American Jews stem from the same impulse: He admires countries that ensure ethnic, racial, or religious dominance. He likes Israel because its political system upholds Jewish supremacy; he resents American Jews because most of them oppose the white Christian supremacy he’s trying to fortify here.

Trump as a White Christian Supremacist is stuff out of badly-written comic books and not worthy of a rebuttal.

Here is where he gives his game away:

Most Zionists aren’t antisemites, of course. But neither are Zionism and antisemitism strange bedfellows. Often, they are different manifestations of the same preference: for nations built on homogeneity and hierarchy rather than diversity and equal citizenship. As such, they are frequent allies in the assault on liberal democracy sweeping much of the world.

Beinart is an ugly American imperialist who demands that all states run on the same model as his does. This is a hatred of the diversity of humankind, and of the world’s various cultures as well.

On European attitudes:

When Kovács and Fischer searched for the factor that best predicted antisemitic attitudes, they found overwhelmingly that the answer was xenophobia. “These data,” they concluded, “indicate that antisemitism is largely a manifestation and consequence of resentment, distancing and rejection towards a generalised stranger.” As Kovács explained to me, the Europeans most hostile to Jews were also most hostile to Muslims, Roma, and LGBT people—other groups viewed as threatening the ethnic, religious, or cultural cohesion of their nations. And the Europeans most anxious about the ethnic, religious, and cultural cohesion of their nations tended to admire Israel, which jealously guards its own.

Can you blame them for wanting cohesion in light of the experience of forced diversity and top-down cultural experimentation? It’s almost as if Beinart fears that the Israeli model will erode liberal democracy in the West because of its relative successes (let’s leave out the occupation in the West Bank and Golan for now, as well as the treatment of the Gaza Strip for another time, please).

On the USA:

This ethnonationalism is also strong on the American right. In 2019, according to the Pew Research Center, most Republicans said that if white people ceased being a majority it would weaken “American customs and values.” More than 60% of Republicans support declaring the US a Christian nation. And, as in Europe, the Americans trying to build a white Christian state see much to admire in the Jewish one. Like Orban and the AfD, American conservatives are particularly enamored of Israel’s immigration system. In 2018, when Israeli soldiers shot Palestinians marching towards the fence that surrounds the Gaza Strip, Ted Cruz declared, “there is a great deal we can learn on border security from Israel.” Later that year, Trump claimed, “If you really want to find out how effective a wall is, just ask Israel.” Tucker Carlson said the same thing.

Now watch this:

But the right’s desire to make America more like Israel often collides with the fact that most American Jews want no such thing. Because Jews are among white Christian nationalism’s most prominent opponents, Trump-era conservatives often depict them as enemies. In the final ad of his 2016 presidential campaign, Trump filled the screen with images of three Jews—Soros, Janet Yellen, and Lloyd Blankfein—while the narrator warned of “global special interests” that “don’t have your good in mind.” In 2018, Rudy Giuliani retweeted a tweet calling Soros the Antichrist.

Beinart is happy to sacrifice the Jewish character of Israel in order to preserve and accelerate the flooding of North America and Europe with migrants from the rest of the world.

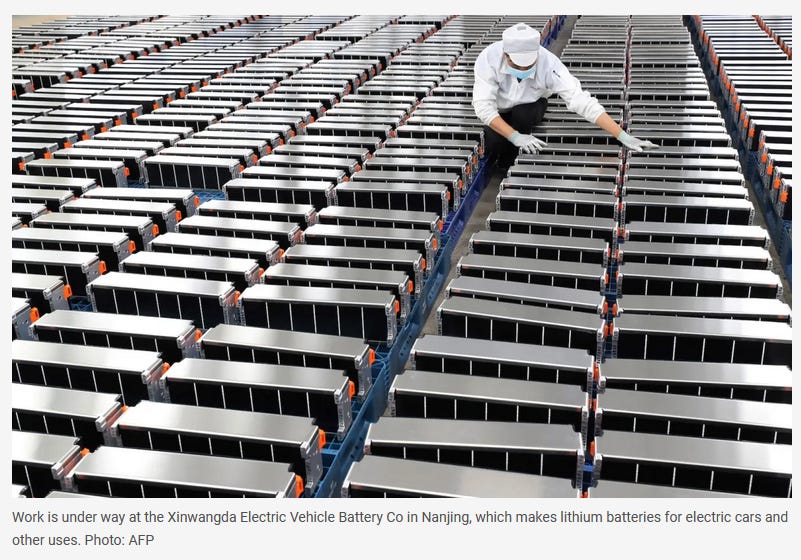

In light of the USA’s moves against China (especially regarding semiconductors), many are predicting the certain and quickly coming death of globalism. COVID-era economics has taught us just how critical control over key supply chains really is, and how it’s not a good idea to outsource absolutely everything that you need to live. The Americans are already re-shoring and friendshoring, and the Chinese are reacting as best as they can (see link above).

Others are watching and making moves too. Joseph Dana explains:

Just as the supply-chain crisis appears to be stabilizing, a new set of laws in southern Africa threatens one of the world’s essential commodities.

Last month, Zimbabwe banned the export of raw lithium. The material is a vital part of batteries that power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles. Zimbabwe is home to the world’s sixth-largest known lithium reserves and has long been an important source for the Chinese market, given the country’s close trade connections.

Will Zimbabwe’s decision usher in a new wave of resource nationalism as other countries move to protect their raw resources from foreign exploitation?

…..or will Zimbabwe suffer regime change? Or will something in-between these two poles happen?

With new semiconductor manufacturing plants in the United States and the slow but steady de-dollarization of the international oil trade, the commodity trade is transforming quickly. Zimbabwe’s move to protect local industry highlights how developing countries could try to protect their resources.

Lithium prices have surged more than 1,100% to record highs over the past two years. Lithium’s value will continue to increase as electric vehicles replace traditional combustion engines. Bloomberg reports that half of all car sales could be electric vehicles by 2030, up from just 9% last year.

Under the new Zimbabwean law, any export of lithium ore (raw lithium) will require special permission demonstrating that the exporter has set up local manufacturing facilities. Foreign companies cannot sell ore but can export concentrates, the powder created from crushing rocks and processing the ore. Exporters that don’t process the ore locally will be required to show exceptional circumstances before moving the raw commodity out of the country.

The high price of lithium has recently attracted a slew of miners targeting abandoned mines in search of rock that might have some lithium. The rock is then exported to other countries. The new laws are designed to stop this activity as well.

The rationale behind Zimbabwe’s decision reflects a new calculus in rising electric-vehicle sales. Instead of supplying raw materials, the country wants to be a part of the manufacturing process.

Zimbabwe’s move isn’t designed to roll back centuries of colonialism. Instead, the government is asking foreign powers to set up local manufacturing centers to get more of the increased revenue generated by processed lithium.

Resource-rich states that are poor have learned that positioning one’s self higher up on the value chain brings greater rewards, and longer-term ones as well.

The Chinese:

The big question in Zimbabwe’s decision will be how China reacts to the ban. In the past year alone, Chinese companies Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Sinomine Resource Group, and Chengxin Lithium Group have begun lithium projects in the country worth a combined US$679 million. Under the new laws, they will be required to build new infrastructure, such as chemical conversion facilities, that can cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Will China apply pressure on the government using all the Zimbabwean debt it holds to get special exemptions? If so, the entire attempt to regain control over the lithium trade will be for nothing.

Two companies – Huayou Cobalt and Chengxin – have started building processing plants in Zimbabwe that would exempt them from the export ban. This raises another question about Zimbabwe’s ultimate goals. If the government forces these companies to open processing plants staffed by Chinese nationals, where is the value of the local economy? Would such a move end up generating much needed revenue for the country? Not really.

What the future holds:

Regardless of viability, resource nationalism will be a central theme in 2023. As the global economy recovers from the supply-chain crisis of the immediate post-pandemic period, new challenges have emerged concerning the technology and raw materials that make our devices (and thus the world) function.

This will be profound in the manufacturing of semiconductors, confined mainly to Taiwan, but will soon expand in deeper ways to the US and perhaps even Europe.

As developing nations continue to struggle with the strong US dollar and hawkish US Federal Reserve, we are bound to see more efforts to control raw materials vital to the economy, including lithium.

Last year, the global economy braced for recession as cryptocurrency and technology stocks collapsed. This year, we might see the start of a meaningful reorganization of the global commodity trade, starting with minerals like lithium and ending with how oil is traded.

The West did not take too kindly to oil-rich countries trying to ensure themselves a bigger share of the revenue back in the previous century. Will resource-rich countries succeed this time around?

We end this week’s Substack with a look at how English Romanticism of the late 18th and early 19th centuries was born in “Germanomania”.

In September 1798, one day after their poem collection Lyrical Ballads was published, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth sailed from Yarmouth, on the Norfolk coast, to Hamburg in the far north of the German states. Coleridge had spent the previous few months preparing for what he called ‘my German expedition’. The realisation of the scheme, he explained to a friend, was of the highest importance to ‘my intellectual utility; and of course to my moral happiness’. He wanted to master the German language and meet the thinkers and writers who lived in Jena, a small university town, southwest of Berlin. On Thomas Poole’s advice, his motto had been: ‘Speak nothing but German. Live with Germans. Read in German. Think in German.’

After a few days in Hamburg, Coleridge realised he didn’t have enough money to travel the 300 miles south to Jena and Weimar, and instead he spent almost five months in nearby Ratzeburg, then studied for several months in Göttingen. He soon spoke German. Though he deemed his pronunciation ‘hideous’, his knowledge of the language was so good that he would later translate Friedrich Schiller’s drama Wallenstein (1800) and Goethe’s Faust (1808). Those 10 months in Germany marked a turning point in Coleridge’s life. He had left England as a poet but returned with the mind of a philosopher – and a trunk full of philosophical books. ‘No man was ever yet a great poet,’ Coleridge later wrote, ‘without being at the same time a profound philosopher.’ Though Coleridge never made it to Jena, the ideas that came out of this small town were vitally important for his thinking – from Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s philosophy of the self to Friedrich Schelling’s ideas on the unity of mind and nature. ‘There is no doubt,’ one of his friends later said, ‘that Coleridge’s mind is much more German than English.’

Few in the English-speaking world will have heard of this little German town, but what happened in Jena in the last decade of the 18th century has shaped us. The Jena group’s emphasis on individual experience, their description of nature as a living organism, their insistence that art was the unifying bond between mind and the external world, and their concept of the unity of humankind and nature became popular themes in the works of artists, writers, poets and musicians across Europe and the United States. They were the first to proclaim these ideas, which rippled out into the wider world, influencing not only the English Romantics but also American writers such as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman. Many learned German to understand the works of the young Romantics in Jena in the original; others studied translations or read books about them. They were all fascinated by what Emerson called ‘this strange genial poetic comprehensive philosophy’. In the decades that followed, the Jena Set’s works were read in Italy, Russia, France, Spain, Denmark and Poland. Everybody was suffering from ‘Germanomania’, as Adam Mickiewicz, one of Poland’s leading poets, said. ‘If we cannot be original,’ Maurycy Mochnacki, one of the founders of Polish Romanticism, wrote, ‘we better imitate the great Romantic poetry of the Germans and decisively reject French models.’

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

For paid subscribers, we are now testing out the chat feature on both Apple and Android phones. If you want to participate, read here.

Over the course of the last few days, I spotted an important indicator of the way the wind is blowing that most people seem to have overlooked: Israel, which is referred to in this article but not for this reason. When the wave of sanctions was unleashed upon Russia, the Israelis pointedly refused to join in. Equally, they have consistently and steadfastly refused to sell weapons to Ukraine.

The reasons for this are not hard to discern. The Russians control Syria and so, in effect, Israel shares a border with Russia. They need continuing Russian co-operation to keep their Northern border secure. There is no way the Israelis are going to antagonise Russia, regardless of the pressure from the GAE or the EU.

Last week, the new Israelis foreign minister made a speech which indicated that the Israelis are now tacking, albeit gradually, more towards Russia. I predict that they will soon cut Ukraine loose altogether.

The Israelis only ever act in their own best interests. I reckon their intelligence apparatus knows exactly what is happening on the ground in Ukraine and they have surmised that Russia is going to win. Moreover, they may also sense the relative decline of the GAE, realise they cannot count on it in future and looking to hedge their bets at the least, or even pivot away altogether towards the new Russia-Asia block.

Your points about Russia display a nation that has a growing confidence in herself and a new purpose. I saw this in particular when Putin opened the new Cathedral of the Armed Forces. They have a certain spirit which the West does not.

I was trying to refer to this when disagreeing with your 'Turbo America' piece and others. Although America has secured some surprise victories these are the consequence of being a former hegemon and the decline not being overnight. She still has a lot of power but the corruption is to her core and cannot be repaired, I don't think. It doesn't mean America is not still dangerous but essentially she is weak and Europe needs to get out from under the collapse. Sadly, we do not appear to be doing anything to protect ourselves.