Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965) - Introduction

FbF Book Club - Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Allan Mitchell, 1965)

When an Anglosphere normie is asked what they think of Bavaria, their mind will automatically scroll through several images including: Oktoberfest, Lederhosen, and Nazis. Slightly savvier ones will have BMW and Audi come to mind, just like Adidas and Puma will for the athletic types and/or sports fans. Munich Re and Allianz will be the response of those familiar with the fascinating and totally-not-boring world of insurance.

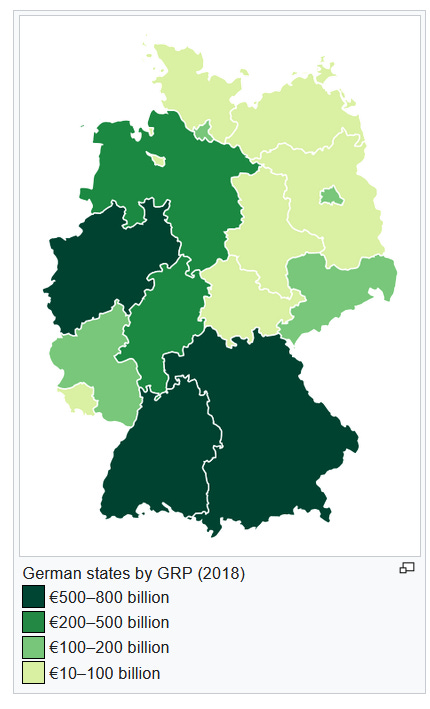

Ask a European today about Bavaria, and they will mention all the companies listed above, but also will note just how wealthy this German state is. The median Euro will describe to you how Bavaria is very clean, orderly, humming with business, a centre of high tech, and a place where you are guaranteed a good standard of living. With an unemployment rate just above 3%1 and GDP per capita of €44,865, life is rather pleasant in the Free State of Bavaria.

On a per capita basis, Bavaria tops both its neighbour Baden-Württemberg and industrial powerhouse North Rhine-Westphalia. Germany’s largest and most southern state is an economic behemoth.

At the same time, Bavarians have the reputation for being conservative in both politics and culture. Unlike Cold War Hamburg or Weimar-era Berlin (two very liberal cities), the Bavarian capital Munich has never served as a magnet for libertinism, like those two cities. Politically under the control of the centre-right CSU (Christian Social Union of Bavaria, the sister party of the CDU/Christian Democratic Union in the rest of Germany), Bavarians like things the way they are, and do not like it when people rock the boat.

With this in mind, we are left asking ourselves this question: how did this very Catholic and ultra-conservative monarchy-within-a-larger-state fall to Bolshevism in the wake of the defeat of the Second Reich in WW2? It is this specific question that we will look to answer by reading through and discussing what we learn in Allan Mitchell’s 1965 book “Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 - The Eisner Regime and the Soviet Republic”.

First of all, who was Allan Mitchell?

He was a specialist in Franco-German affairs, focusing on the period beginning with the revolutionary year of 1848, through to the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), the Second Reich and its continued rivalry with France, and all the way up to the initial post-WW2 period.

From two links above:

His academic qualifications were irreproachable: a BA, Phi Beta Kappa, from Davidson College; two MA degrees, one from Duke University in history, the other from Middlebury College in German; Fulbright years abroad in both Germany and France; a PhD in history from Harvard University. He was inspired at Harvard by William Langer, one of the foremost diplomatic historians of his time, and by the eminent intellectual historian H. Stuart Hughes. His PhD in hand (or in a file cabinet), Allan easily ascended the academic hierarchy: first at Smith College, in Northampton, Massachusetts, where he remained for ten years, and then at the University of California at San Diego. Both Smith and California offered him opportunities for extended residence abroad, which, along with his previous extended stays, gave him a profound grasp of the languages and cultures of France and Germany. He could even read with ease old-fashioned German handwriting—a skill that even many native-born Germans lack today, but one that is crucial for dealing with nineteenth-century German archives.

Why This Book, Niccolo? Why?

There are many reasons. Allow me to explain at length:

The triumph of western liberalism over fascism in 1945 and communism in 1989 meant that liberals were the only victors left standing on the global stage by the last decade of the 20th century. This meant that they now had a monopoly on how we were to understand the history of the last 80 years or so thanks to their interpretations based on their worldview. With fascism being Enemy #1 and communism a close second, their historical narratives leave a lot to be desired as to how these two radical political forms came about, as liberal historians are often self-serving court historians, with their work serving the regime and its ideological underpinnings.

Ask a normie why Mussolini managed to seize power in Italy and they will struggle to formulate an answer. Ask another normie why the Spanish Falangists initially posed a threat to that country’s landlords and they won’t have a clue as to what you’re talking about. Fascism in the normie western mind is understood as people who hate others and want to destroy them by any means necessary. There is little desire to try and learn why such movements came about; they were always “just there”, even though we knew that they weren’t.

Take Germany for example where the normie timeline goes as follows:

Funny-helmet Germans go to war with Russia on the eastern front and with France and the UK on the western front

Germans lose

Treaty of Versailles carves up Germany, Germans mad

Weimar Republic founded, hyperinflation follows

Hitler launches a Beer Hall Putsch that fails

Weimar Germany is a wild party culture that produces so much great art

Great Depression happens, Nazis form government

There is quite a lot missing from this timeline, and we cannot blame the normie for failing to possess many important facts (and the nuances and contexts that come with them).

The most important piece missing in the mainstream narrative is just how close large parts of Europe came to being captured by radical Bolsheviks shortly after the end of the First World War. Inspired by the shock of the Soviet capture of Imperial Russia, communists in Berlin, Hungary, and Munich launched revolutions in which they were convinced were going to succeed. These successes and failures were bloody, and they showed to the world just how much these Reds meant business. These communists had the fervour and zeal of the convert reminiscent of the Medieval Era.

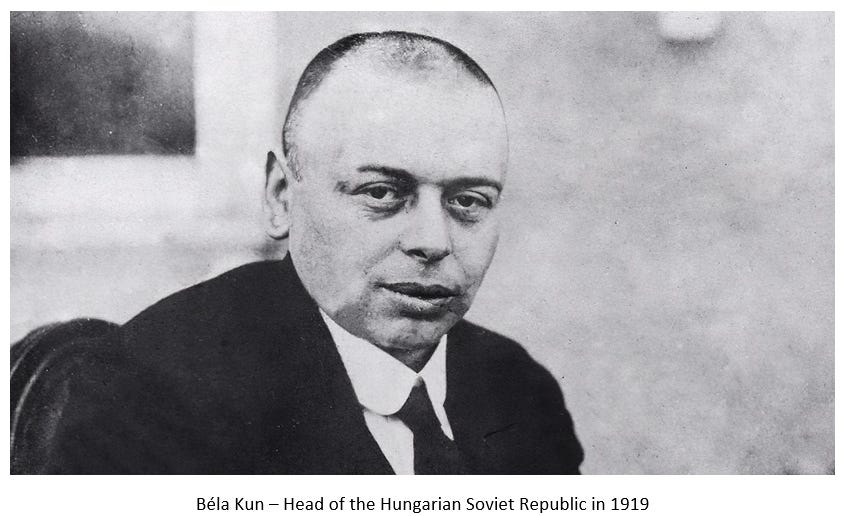

Bela Kun and his comrades seized power in Budapest and set up a Soviet regime over what was left of Hungary. The Spartacists attempted to do the same in Berlin, but failed. In Bavaria, the Reds had more success than their comrades in the German capital. One by one, major cities were falling to the Soviets, and Europeans were frightened, as the butchery, outrages, and crimes of the communists in Russia was by then well-publicized in the rest of Europe. The first “Red Scare” put the fear of God into those Europeans who were afraid that they would end up like the victims of communism in the East. The whole of Europe was on edge.

The threat of “Global Revolution” resulted in a reaction, always bloody, in which these communists were removed from power and often liquidated. The threat that they posed to order had people clamoring for someone to step in and clean up the mess that was left in the wake of the First World War. Democracy was seen by many as a luxury that could be ill-afforded in times of crisis. Reactionary elements stepped in to restore order and undo what was done by the communists. Some of these reactionary elements eventually became fascists.

I have mentioned how fascist elements in Europe are assumed to have been present all along, a view that is historically ignorant. Fascism was a product of its time. At the same time, many do not understand why Bolshevism was so appealing to so many Europeans at the time. In order for us to obtain the full picture, we must understand the forces that created both of these radical trends in European politics and governance. They did not appear in a vacuum.

We will delve into these matters as we proceed through the book. Suffice it to say for now, Marxists of various stripes, ranging from social democrats to Bolsheviks, saw how late 19th/early 20th century industrialization and rapid urbanization, combined with increasing levels of literacy and economic inequality, laid the groundwork for what came to be known as “mass politics”. They seized on this burgeoning constituency and captured large parts of it thanks to the dissatisfaction of these same masses with their material conditions. The ruling elites, often aristocratic, were distant, and view the masses as asses. In short, they ceded this new and growing constituency to the Marxists.

The reactionary politics that followed the First World War understood that the pre-war elites shot themselves in the foot by ceding these masses to reformist and/or revolutionary forces. Fascism was the vehicle in which the masses could be attracted to reactionary politics out of fear of or disgust with Bolshevism. The rise of Fascism was a belated recognition that the elitist politics of old were dead and buried, and then mass politics would rule the day.

I chose Mitchell’s book because the Bavarian Soviet Republic is a) lesser known than the Spartacist Revolt in Berlin (thanks to the cults of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht), and b) because it was much more successful than the attempt in Berlin. Beyond that, Bavaria quickly became the most reactionary state in Weimar Germany, seeing it bounce from one extreme to another. Even though the Spartacists failed in their putsch in Berlin, the German capital remained quite red until the Nazis entered government in 1933.

I also want to use this historical episode to highlight how events can spiral out of control when disasters such as the First World War happen (especially when you lose a war). At the same time, I want all of you to try and draw parallels with contemporary politics to see what matches, and just as importantly, what doesn’t. In this book, we’re going to see a breakdown in law, order, and society, with significant violence as a result. We are also going to witness how zealous individuals can change their world through cunning, bravery, planning, and above all else, opportunism.

Action breeds reaction. We cannot understand reaction without understanding what it is reacting to.

Note: We will dive in with a history of Bavaria from the 19th century through to the end of the First World War. I aim to have this entry up by Sunday this weekend as I have already compiled my notes.

I anticipate that we will have around 8 entries in this book club.

For those who cannot find a copy of the book but want to participate, I can lend you one.

For those wanting to participate, click the Subscription button here:

“The German Labour Market in 2022”, Federal Employment Agency - Statistics/Labour Market Reporting (.pdf upon request)

For those who cannot find a copy of this book, I can lend you one.

Hit the like button at the top of the page to like this entry. Use the share or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

For those who are not paying subscribers, consider joining us. I hope to stir some good discussion on the subjects that we will be tackling in this book.

Always a fan of the book club (many other book discussions are self aggrandizing and off putting). Just a minor footnote, Finland also had a Bolshevik revolution but was put down almost immediately (the often overlooked short lived Finnish civil war) that just reinforces the point that this was a memeplex that completely spread across Europe (pre-internet as well for all those ppl who love to blame the internet/social media for all their woes)

Looking forward to it!