Chapter 3: The November Revolution

FbF Book Club: Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965)

Previous Entry - Chapter 2: Kurt Eisner

It took one, single day of organized action for the centuries’ old Kingdom of Bavaria to fall apart and for King Ludwig III to be overthrown.

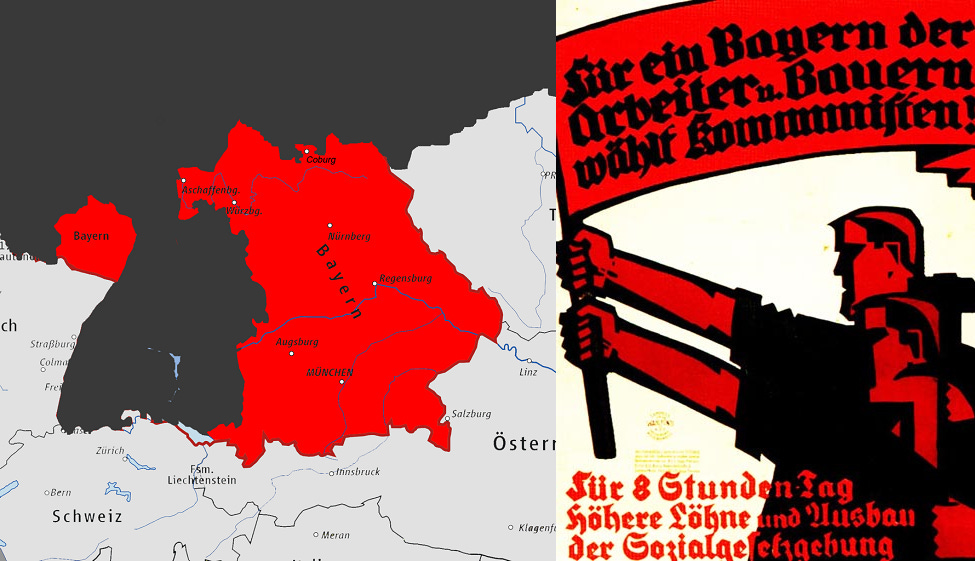

What makes it even odder is that there was no real agitation to end the regime, dissolve the monarchy, and support republicanism, especially in light of the fact that all the major political groupings represented in the Landtag agreed on a compromise package to reform how the kingdom would be run. A deal was agreed by all relevant parties, and the “docile” Bavarian people did not object to it…with only a few exceptions1. It was most of these exceptions2 that brought down the Wittelsbach Dynasty on November 7, 1918 in the Bavarian capital, Munich.

Mitchell asks how it was possible for the revolution to succeed in light of this. He offers up two explanations, the first being:

How was it then still possible for a revolution to succeed? One explanation is simply that most people did not have time to comprehend the importance of the reforms. If it was not a case of too little, it was certainly too late. Most of the visible signs of the old regime, moreover, were left in full view. For most Bavarians the King was the symbol and the Upper House the embodiment of traditional authority—they were both to remain. The new cabinet would be led by the same Prime Minister, and the Center Party would retain an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies, at least until new elections were held at some undesignated time in the future.

This answer is not fully satisfactory. Mitchell instead provides a more ‘fundamental’ answer; that the constitutional reform could not end the war, a war that was clearly failing.

By January of 1918 (as you recall, the only time that any significant, radical labour action took place in Bavaria during the war), the German High Command was worried that the introduction of American forces on the Western Front would tilt the balance against the German Reich. With reinforcements available now that the Eastern Front was no longer a threat thanks to the Russian Revolution and the end of that empire’s active involvement in the war, General Erich Ludendorff decided to place all of his country’s stakes on one huge gamble in the west. Conscious of the fact that the naval blockade of Germany was now really biting into the war effort, so much so that food security and hunger was now significant issues, Ludendorff and his staff came up with a plan to decisively end the war before the American advantage could present itself.

The German Spring Offensive of 1918 initially scored some successes, but problems in logistics and a reorganization of Allied command halted Ludendorff’s attempt to split the British forces from the French. From the link in the previous sentence:

A further attack on the River Aisne at the end of May (Operation Blücher) netted the Germans another 40 km, but their strategic aims remained beyond their grasp. Each advance only stretched their dwindling resources. German factories, starved of materials by the Allied naval blockade, struggled to replace the weapons and equipment that had been lost. Between March and July, the German Army lost a million men killed or wounded, including many irreplaceable experienced and elite soldiers. In desperation, the German authorities began sending 17-year-old conscripts to the front.

Ludendorff’s bold gamble had failed by the middle of that summer, and the news managed to trickle back home:

Munich was a different city from the one which Eisner had left in January. The confidence and high spirits on the home front which had buoyed LudendorfFs drive in the West had been, like the military offensive, broken. The news of impending defeat and the imminent necessity of seriously compromised negotiations had been taken especially hard by a people long kept ignorant of the facts and then suddenly confronted with them. It was not only a universal weariness with the war effort. "In October of 1918," one Liberal writer admitted, "we finally considered ourselves, everyone without distinction of party, deceived and duped."

Recall that Mitchell described the Bavarians of that time as “docile”. Docility was in large part present because Bavarians, like other Germans, were under the impression that the war was being won, albeit very slowly. All the perceived excesses of the war regime, particularly increased centralist control from Berlin in matters like agriculture, could be forgiven so long as victory was assured.

Preventative Measures

The stunning news of failure on the Western Front aggravated the hostility to Berlin over its wartime management, and it also created a crisis of legitimacy in the regime as it could no longer be trusted to tell the people the truth. “Among the dissatisfied there was open talk of "swindle" and, as officially reported to Berlin, an intensified attitude of "wearied disgust" toward the Empire (Reichsverdrossenheit)”, said a report to German Chancellor Georg von Hertling. Mitchell lists the two most important errors made by the Bavarian regime in the second half of 1918:

that they had the situation under control

confusing the passivity of the populace with loyalty to the status quo

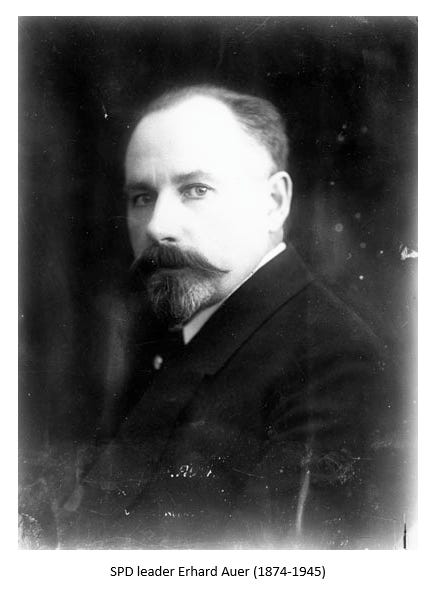

Much as in the rest of Germany, the Bavarian Government had to open up discussions with the SPD (Soc-Dems) in order to shore up the regime in the wake of the disaster on the Western Front. The price for cooperation in Bavaria was constitutional reform, which was then delivered on November 3rd. The SPD, under new leader, Erhard Auer, committed itself to helping maintain order while obtaining these concessions, proving that its reformist-not-revolutionary approach would bear fruit.

Auer was also entrusted with restraining the newly-released from prison Kurt Eisner, a task that he assured the government his “disciplined” SPD could be trusted to accomplish. Bavarian authorities must have thought that Eisner’s release from prison would weaken the opposition SPD, but was not strong enough to threaten actual order. As we will see, this was another massive mistake committed by the regime.

Auer’s restraint, typical of the Bavarian SPD:

We are living through the greatest revolution which has ever occurred. Only the form is now different; different because other forms are possible . . . through the discipline of the working population, because it is possible to achieve in a legal way that for which we have striven for decades." Two things were characteristic of this statement, and were to be typical of Auer from this time until the revolution was an accomplished fact: the notion of a gradual and entirely peaceful transition which had already commenced, and an unmistakable ambiguity as to its objective.

“Revolution” through legalism and gradualism.

Ambiguity:

The Party resolved to support "the transformation of Germany into a Volksstaat with complete self-determination of the people in nation, state, and city." Since it was well known that “Volksstaat" was the generally accepted Socialist euphemism for a republic, this was presumably a demand for the Kaiser's abdication. But the terms of the statement might have been fulfilled just as well by a constitutional monarchy as by a republic, providing that "the people" so determined; and it was conspicuous that no precise reference was made to the future of the Wittelsbach dynasty.

And some populism aka ‘Bavarian Particularism’ for good measure:

He was persistent in his denunciation of "the hegemony of Prussia which . . . was and is the misfortune of Germany." But he wavered between demanding that "the present system must be discarded root and branch" (in reference to Berlin)…..

Bavarians were quickly turning against the war which they now learned was in danger of being lost, shortages were becoming more pronounced, and the SPD had managed to wring concessions out of the regime which was growing fearful for its continued existence. At the same time, all of the Bavarian elites and centres of power were still onside with the now-reformed regime.

So what went wrong?