Previous Entry - Chapter 1: The Origins of the Revolution and the War Years

In the first chapter of the book, Mitchell sets the stage for the revolution by arguing that although it took everyone by surprise, it was still the result of a progression of reforms that saw Bavaria transition from a strong monarchy to a “ministerial and bureaucratic oligarchy”, through to a parliamentary system in the 100 years prior to it. The revolution was a culmination of this progress combined with the dissipation of the rule of law, allowing opportunists to seize power.

These opportunists were radicals, in a state and kingdom where radicalism barely existed. They were empowered by earth-shattering events in other parts of Europe, especially the failing German war effort. Their numbers were bolstered by the demographic changes that swept parts of Bavaria during the war, specifically the arrival of tens of thousands of industrial workers who were employed at new factories near Munich and Nuremberg. Lastly, these opportunists managed to capitalize on the growing disaffection of Bavarians toward Berlin, and its centralization of power in the name of greater economic efficiency to support the war effort.

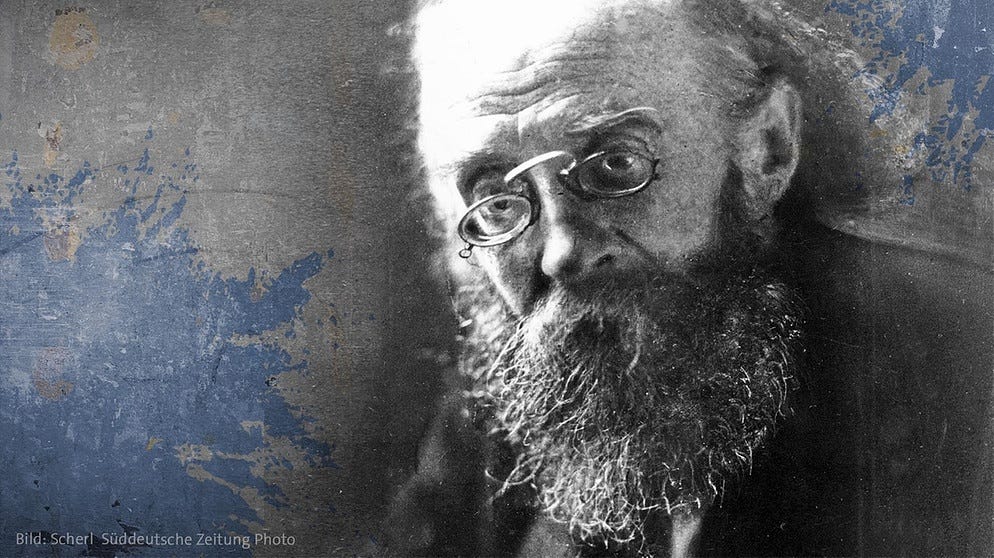

In the second chapter of this book, Mitchell introduces one of the main characters of this story, Marxist journalist and literary critic, Kurt Eisner. For three decades he contented himself with tossing witty bombs and lobbing irony-laden grenades at the establishment, especially the Prussian Aristocracy, in his writing. Somehow, he managed to become a revolutionary leader despite never having an actual following. Add this fact to the pile of surprises that characterized the revolution in Bavaria, which Mitchell describes as: “the first direct assault on the tradition of monarchy and, as such, removed the final restraint to revolution in Berlin.”

Enter Stage Left

Kurt Eisner never set foot in Bavaria until he was in his 40s. The son of a “modestly affluent Jewish shopkeeper” who “specialized in military accessories and decorations” and had a tony address on the Unter den Linden, Eisner was born in the German capital of Berlin in May of 1867. An attendee of elite schools throughout his early life, he ended up at Friedrich Wilhelm University studying Philosophy, only to drop out in order to begin a career in journalism (which Mitchell explains was due to the faltering financial situation of his father’s out-moded business). Mitchell on his writing:

His published writings, though scarcely known today, still comprise one of the wittiest and best informed commentaries on the public and political life of Wilhelmian Germany. Eisner's wit ranged from light satire to virtually unleavened irony……

This description suggests that Eisner would have been a good “shitposter”, in today’s parlance. The journalist-to-revolutionary pipeline is not an uncommon one; Benito Mussolini is one of the best examples of this professional trajectory.

Hired by the Frankfurter Zeitung in the 1890s, Eisner began to become attracted to the politics of the SPD (Social Democrat Party), something that he had shown scant interest in while living in Berlin. It was here that he finished his first book, a “study of the work and influence of Friedrich Nietzsche”. It’s important that we excerpt some of his thoughts on the notorious German philosopher because it illuminates his own political views at the time. Per Mitchell:

Above all, Eisner was sympathetic to Nietzsche's repudiation of the cultural mediocrity of the new German Reich, and to his rejection of the institutions whose primary function seemed to be the perpetuation of privilege: the parliaments, the press, the schools, and especially the universities—"these penitentiaries for bureaucrats are too confining for greatness." But in Eisner's view Nietzsche was a better poet than prophet:

"Everywhere he detects the weaknesses, the diseased places, with an uncanny perspicacity, but he errs in the discovery of causes, and he loses himself in magic witch-doctoring in his attempts to heal."

and

The congenital flaw of Nietzsche's philosophy, Eisner thought, was his "unreal vision of a master morality." Nietzsche was an egotist. His moral universe was all too neatly divided into two spheres: above, the select and superior few; below, the many, the masses, the "human worms." In this respect he shared something with Goethe, though Goethe's "healthy universality" contrasted with Nietzsche's chronic "illness of creative excitement."

Eisner and Nietzsche both found the Second Reich wanting, but for totally different reasons, as we can see here:

Purposely or not, Eisner observed, Nietzsche had emerged as a central figure in the cult of European decadence. His name was becoming a rallying-cry for an assortment of megalomaniacs, imperialists, free-traders, Social Darwinians, East-Elbian Junkers—for all those who claimed the right of the stronger. Eisner denied that Darwinian theories of biological evolution could be literally transposed to the field of public morality, and he accused Nietzsche of having given his name, perhaps unwittingly, to the apologists of social injustice. "The 'struggle for existence' is no justification for the oppression of the sick and the weak, nor is it a way to the superman."

Eisner’s worldview was therefore a moral one….one that required a social justice for the poor and the oppressed.

Eisner cited the fact that Nietzsche was an outspoken misogynist, a quirk which was probably "to be explained medically." He also regarded Nietzsche as an anti-Semite, contaminated with "racial fanaticism" by his sister and her husband.10 This, in turn, had led Nietzsche to oppose Socialism as "the consequence of the Semitic slave morality." Eisner regretted that Nietzsche hated Social Democracy without knowing anything of its positive goals and ideals. His own attitude and his case against Nietzsche were best summarized by a single phrase, when he called Nietzsche "the most dangerous and most seductive opponent of Social Democracy."

Even though both he and Nietzsche saw the Second Reich as lacking in greatness, what constituted “greatness” in their minds occupied two different poles.

Eisner’s term in Frankfurt was a short one, moving to nearby university town Marburg to take up a position with another publication. Mitchell says that it was his time spent in this town that saw him become a fervent disciple of Marxism, via a route leading from Immanuel Kant, and with the assistance of a professor named Hermann Cohen. This academic’s influence convinced Eisner that Kant’s ethics were compatible with the objectives of socialism.