Chapter One: The Origins of the Revolution and the War Years

FbF Book Club: Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965)

Previous Entry - Introduction

The collective meltdown experienced by US elites and tens of millions of Americans in the wake of Trump’s surprise 2016 victory over Hillary Clinton had the net effect of convincing many, many people that the USA (at least its constitutional order) was in an existential crisis. Fears of regime collapse and/or civil war breaking out became commonplace, with many (including readers at this Substack) still convinced that this could or will happen in the near future, seeing the USA as a crumbling polity politically, culturally, and so on.

The media-driven psychosis of the past almost-decade makes this view understandable, even if I disagree with these predictions of collapse. Constantly stoking the fire of extreme partisanship, the media has been very responsible for creating mountains of molehills, each one successively more existential in importance than those that preceded it. People have been left with a sense of continuous crises rocking their nation, with compromise all but impossible. When compromise is impossible, the door to brute force is opened. This was the story of 1930s Spain, where civil war was inevitable, and everyone could see the march towards it, helpless to stop it.

Michel Houellebecq once wrote: “anything can happen in life, especially nothing”. What he meant is that we humans are so self-obsessed, so wrapped up in ourselves and the story that we think that we are living in, that we are convinced that our lives will be filled by story-like narratives with their buildups, denouements, resolutions, and so on….except that it quite often doesn’t happen in that way. This is how I feel about the United States of America today, a country I view as incredibly resilient, with an elite that is very unified (and more distant than ever from its fellow non-elite Americans), and with economic and political power that is unrivalled, at least for now. Expectations do not always pan out.

Karl Marx had his own expectations, foremost among them that socialist revolution would break out in the most advanced capitalist countries first for the myriad of reasons he listed in his writings. He would have been shocked to have learned that it was backward Russia where revolution first took place, and where it first succeeded. Russia, a largely agrarian society only a little over two generations removed from feudalism, lacked the heavy industry of capitalism, and the large proletariat that was exploited by it, the cohort that would seize the means of production. The Russian Revolution was unexpected:

But October was not the revolution Karl Marx had had in mind. He expected oppressed factory workers to seize power in the wealthiest, most industrialized capitalist societies.

The point is: history throws up surprises all the time. The Russian Revolution was a surprise. So was the Bavarian one, the subject of this book club.

In this first chapter, Mitchell sets the scene for the revolution by looking at the previous 100 years of Bavarian history, including the four year long period known to us as The First World War. Mitchell opens up the chapter with a strong statement:

IT HAS usually been said of the 1918 revolution in Bavaria, as of the German revolution in general, that it was the result of a collapse rather than a seizure of power. There is no reason to resist this view except that it may provide an excuse to avoid the difficulties of locating the sources of revolution. Bavaria was no doubt suffering in November of 1918 from a temporary political insanity. But anarchy in itself does not explain the revolution unless one knows how a hiatus of public authority occurred, who was prepared to take advantage of it, and by what means a new order was imposed.

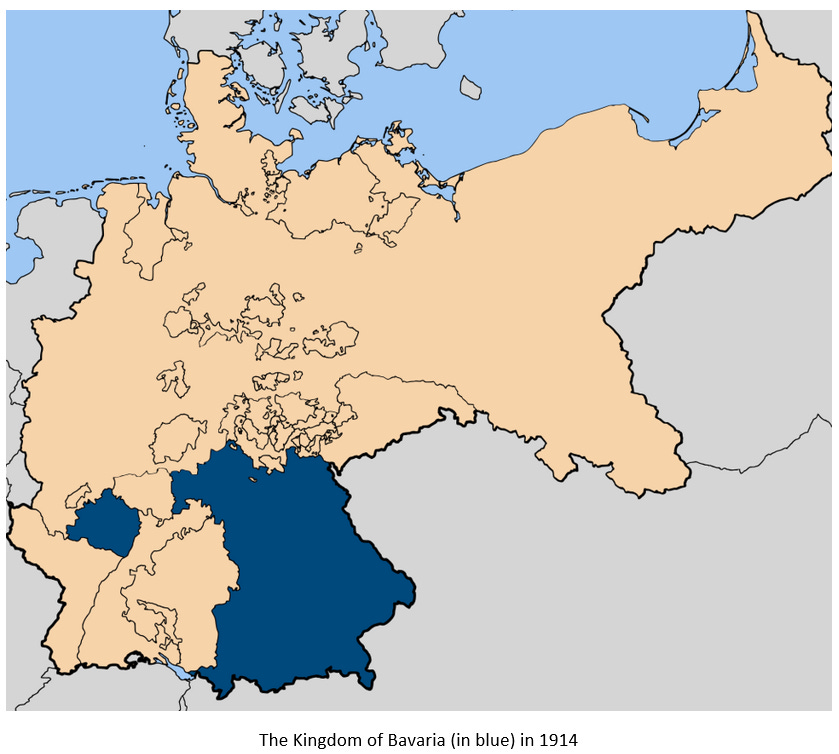

The Kingdom of Bavaria, that ‘rural, parochial, and predominantly Roman Catholic” autonomous state of the Second German Reich, was the least likely of all the larger German states to fall victim to a socialist revolution thanks to the following factors:

a lack of heavy industry/industrialization

little urbanization, meaning no significant proletarian population from which to draw from for the sake of revolution

less economic inequality than elsewhere in Germany

an absence of left-wing radicalism, whether in parliamentary chambers or through direct labour actions such as strikes

What happened in the late autumn of 1918 took everyone by surprise. Mitchell argues that this surprise was a culmination of the decades’ long series of reforms that saw Bavaria move away from monarchical rule towards parliamentarianism via mass politics, with a long period in between that saw the rule of a “ministerial and bureaucratic oligarchy”:

The revolution did terminate the monarchy, but more importantly it continued social and political developments already well advanced. For most of the century —excepting the three decades before 1848—the Bavarian monarchs were dominated by a ministerial and bureaucratic oligarchy. After 1890 a transition began toward the establishment of parliamentarianism. This was achieved in all but constitutional law by 1912. The revolution was to change the law and to secure a parliamentary system based on political parties. In this sense, far from being an aberration from tradition, the revolution came as a concluding episode in the accomplishment of reform.

All it took was a little opportunism from determined individuals who were well-organized and highly motivated. But we are jumping too far ahead.

Mitchell agrees that Bavaria was the least likely candidate for such a revolution to take place:

Measured by the usual standards of the nineteenth century, industrialization and urbanization, the state had experienced a remarkably lethargic development. Rural, parochial, and predominantly Roman Catholic, Bavaria seemed to offer an unlikely setting for political insurrection. Moreover, Social Democracy in Bavaria was the most moderate, the most outspokenly reformist representative of Socialism in all of Germany. It is virtually impossible, in fact, to locate anything which might properly be considered a radical movement in Bavaria before 1918. Yet Bavaria was the first of the German states to become a republic and the last to be released from the grip of radicalism.

It shouldn’t have happened, but it did, and it was the culmination of a decades’ long progression of reforms. Confusing, to say the least. Patience is required, as we are only at the beginning of this story.

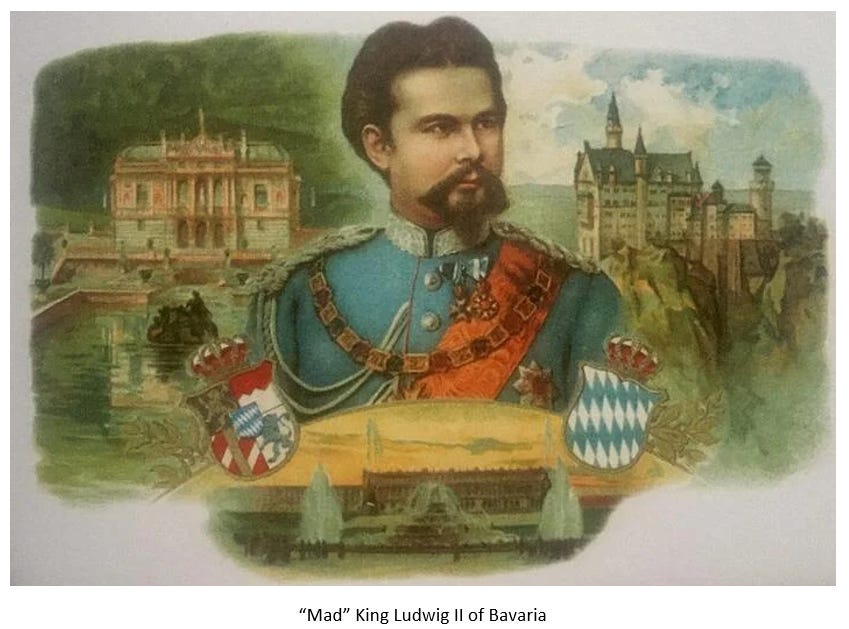

The story of 19th century Bavaria is the story of transition. From the reactionary rule of Ludwig I (who viewed his ministers as “advisory, only”), to the “ministerial and bureaucratic oligarchy” that ran Bavaria under two insane kings (Ludwig II and Otto), through to the rise of the Catholic ‘Zentrum’ (Centre) Party, and the arrival of the Social Democrats (SPD), who, together, managed to introduce the kingdom to the era of Mass Politics, leading to almost-universal suffrage, while ending the rule of the oligarchs.

What we see in this timeline is an actual historical progression, albeit one that was both lagging behind much of the rest of Western and Central Europe, and one that was devoid of the radicalism present elsewhere. Bavarians were not revolutionaries, with Mitchell going as far as to characterize them as “outwardly docile” even during the First World War. Bavarians seemed content with their station, autonomous within the newly-founded Second German Reich, the result of the Prussian victory over the Habsurg Empire in 1866. Total independence for Bavaria was not a serious consideration per Mitchell: “The idea that Bavaria should organize a southern union as a third force in a confederated Germany never became a concerted policy or a serious alternative to Bismarckian unification.”

Bavaria as “special”:

The federal character of the Bismarckian settlement was something of a fiction—except for the maintenance of the state bureaucracy, whose function and personnel were scarcely affected by national unification. The special concessions granted to Bavaria, notably the state administration of beer and brandy taxes, assured the continuation of ministerial control in state policies.

……..

By 1870 Bavaria may have reached "the terminus of its history" as an autonomous state, but within its borders the conduct of government remained as before in the hands of "the combined ministers of state."

Business as usual for the Bavarian elites (and people).