The Spanish Civil Part 2: El Bienio Negro - Conservative Reaction & Leftist Rebellion (1933-36)

CEDA takes power, revolt in Asturias, more political violence from Anarchists, the ebbing of support for democracy on all sides, extreme polarization sets in

(Note: The first entry in this series was the result of answering a question that was posed to me regarding why certain Spanish military brass revolted against the Spanish Government in 1936. A gap in knowledge led some people to ask me this question, which is why the introduction to this series was not a fair and balanced one. Going forward, I will strive to present the positions of all the major players as objectively as possible. For those who asked me the original question that launched this series, you should be able to easily deduce the answers after the first phase of this series is completed.)

Previous Entry - The Spanish Civil War in Retrospect: Why Did Spaniards Rebel Against Their Government?

In 1930, almost half of all Spaniards over the age of 10 were illiterate.1 The country was still overwhelmingly agrarian, with a small number of very wealthy landowners owning about 2/3rds of all the arable land in Andalusia alone, employing almost a million landless campesinos at barely subsistence-level wages. Industry was almost entirely found only in the north and northeast. Industrialization was beginning to pick up pace by the turn of the century, but was still very far behind the rest of Western Europe by the time the Second Spanish Republic came into being in 1931.

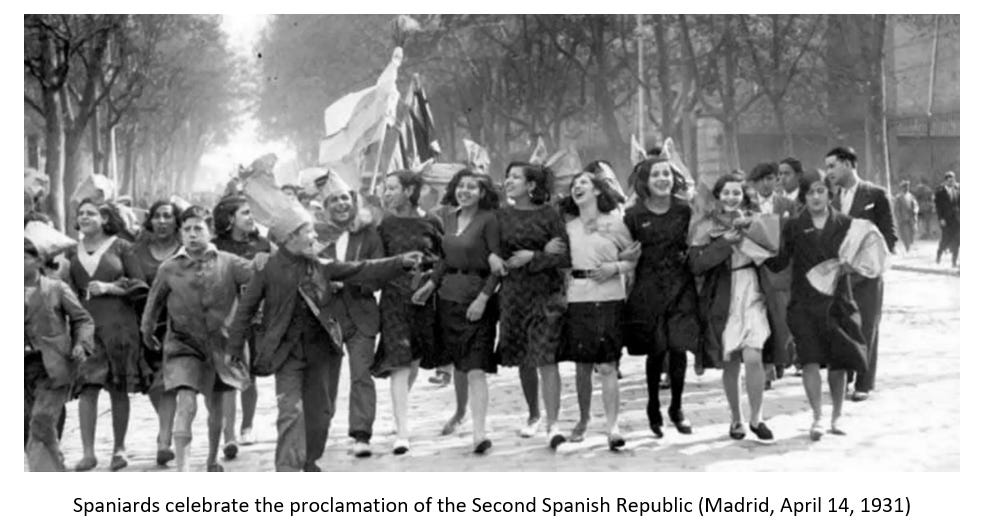

Despite Spain having one foot in the past, its other foot was in the present, a present that was rapidly changing and very unstable politically. The loss of confidence in King Alfonso XIII on the part of the middle and upper classes led to his abdication which opened the door to the establishment of the Second Republic, a democracy in a time when democracy itself was under attack throughout Europe, having already lost in Russia and Italy, and on its way to disappearing in other countries, most notably Germany.

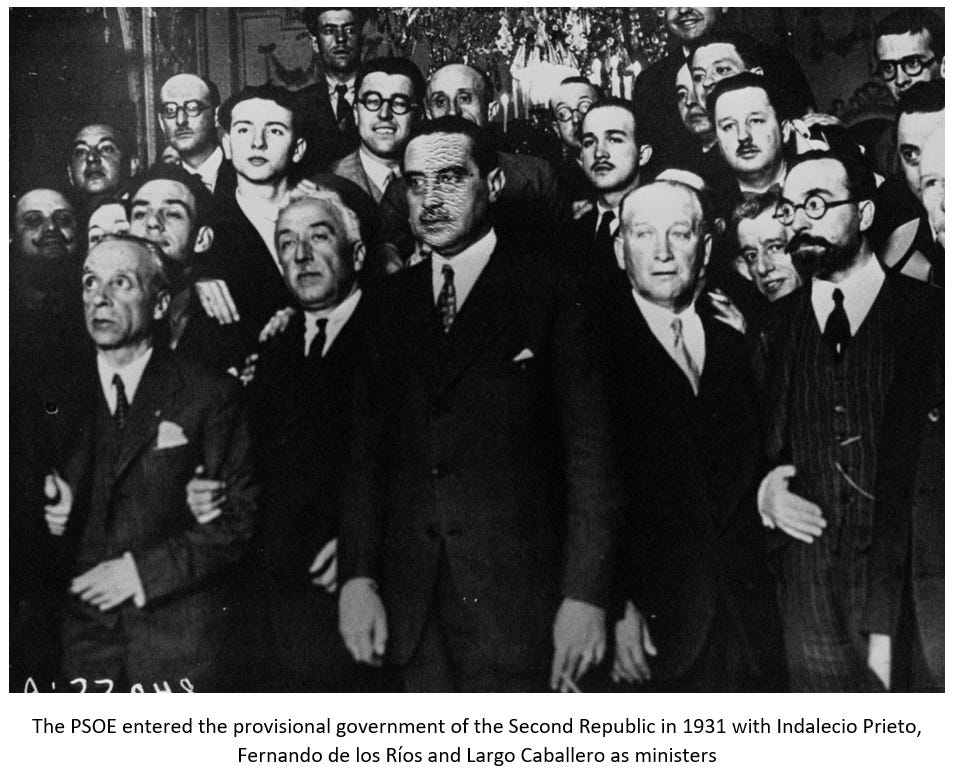

The end of the monarchy was celebrated throughout the country (with some exceptions), but not always for the same reason. Yes, anti-monarchist forces viewed the monarchy as retrograde and out of step with the modern era, but only the liberals and various republican parties were committed to democracy and parliamentary politics. The Socialists (PSOE) for example, were riven by factionalism and a generational divide whereby there were those who sought to use power in office to both settle scores with their old enemies in the military, the landowning class, and especially the Catholic Church, and to actually launch a revolution along Marxist lines. For them, the Second Republic was a vehicle for a larger goal, and not an end goal in and of itself. Anarchists celebrated the end of the monarchy, but they were opposed to any and all government on principle. For Anarchists, the Second Republic was also a path towards revolution as well. For Catalan separatists, the Spanish Second Republic was a stepping-stone towards independence, or at least towards as much political and economic autonomy as possible.

Conservatives were in a state of disarray upon the establishment of the Second Republic. Despite this condition, all the factions that could be grouped as “conservatives” largely supported the new regime2…..at least at the outset. Once the agenda of the first government of the Second Republic was made public, opposition began to harden.

Rather than trying to generate a grand consensus among the various factions that dominated Spanish politics, economics, and society in 1931, the liberals, republicans, and socialists who led the country from 1931-33 instead chose to attack the core interests of their political rivals to the right. The military was to be slashed via the retirement of a large number of its officer class, land was to be seized from wealthy landowners in order to redistribute it to the poor and landless, and the Catholic Church was to be stripped of its role in educating young Spaniards, with the Jesuits expelled from the country altogether, and many churches, convents, monasteries, episcopal residences, parish houses, seminaries, etc. expropriated by the Spanish state. Private Catholic schools were also expropriated and turned into government-run ones instead. The Church was also forced to pay taxes and was banned from all industry and trade, “…..enforced with strict police severity and widespread mob violence.”3

These attacks on the Catholic Church (which also saw the torching of churches, monasteries, and convents in 1931 as we saw in the previous entry in this series) resulted in the release of a Papal Encyclical by Pope Pius XI on June 5, 1933 entitled “Dilectissima Nobis”. In this encyclical, Pius XI decries the persecution of the Church in Spain, and asks Spanish Catholics to defend themselves and the Church from attacks by the government. He describes the attacks as “…[an] offense not only to Religion and the Church, but also to those declared principles of civil liberty on which the new Spanish regime declares it bases itself". As we already saw previously, then-Minister of War in the Spanish cabinet, Manuel Azaña, famously declared that “All the convents in Spain are not worth a single Republican life”.4

There was no attempt to build a solid democratic foundation for the Second Republic whatsoever. Instead, a cultural revolution was quickly ushered in, and an agrarian revolution was threatened, but only implemented half-heartedly. The first government of the Second Spanish Republic managed to alienate the military, the landowning class, conservatives, and the Catholic Church overnight.

On the other side of the political divide, the centrists were attacked from the left for not going far enough, fast enough. Campesinos and small landowners demanded immediate expropriation of latifundia estates to be redistributed to them. The youth wing of the PSOE urged the nationalization of all industry, which led to factionalism within the socialist groupings. Less radical socialists pointed to the extension of voting rights to women, to the enshrining of the 8 hour workday in law, and to the increase in wages for industry workers as the biggest successes of the first two years of the Second Republic. These radical factions were not content with these incremental gains, and demanded “more, now!”

This radicalism culminated in the “Casas Viejas Incident”, which I described in the previous entry:

Staying true to form, the anarchists were restless and, as is their nature, opposed the present government in Spain as they opposed all governments, viewing them as inherently oppressive. Their massive labour union, CNT, led by the vanguard of FAI, began demonstrations in various locations across the country, with the greatest actions taking place in Andalusia. Political violence ensued, with two Civil Guards wounded. The Assault Guards, set up by the new Constitutional authorities in the Republic to provide a new force to purportedly protect those who lacked protection under the Monarchy, raided the village of Casas Viejas near Cadiz. They encountered a group of anarchists locked in a house and set fire to it (while disarming others in the village who were armed), and then executed them.

This act of state violence was committed not by fascists, nationalists, royalists, or even conservatives. It was committed by a liberal-socialist regime and its purposely-created security force, against anarchists. All the parties involved in this incident would find themselves on the same side in the not-too-distant Spanish Civil War.5

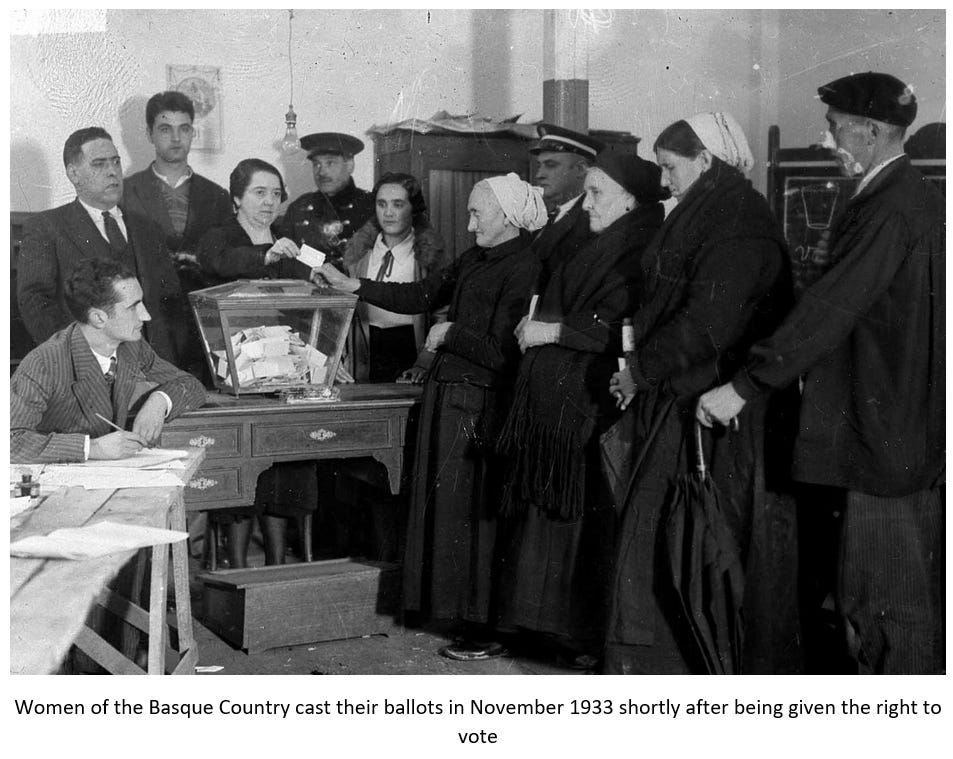

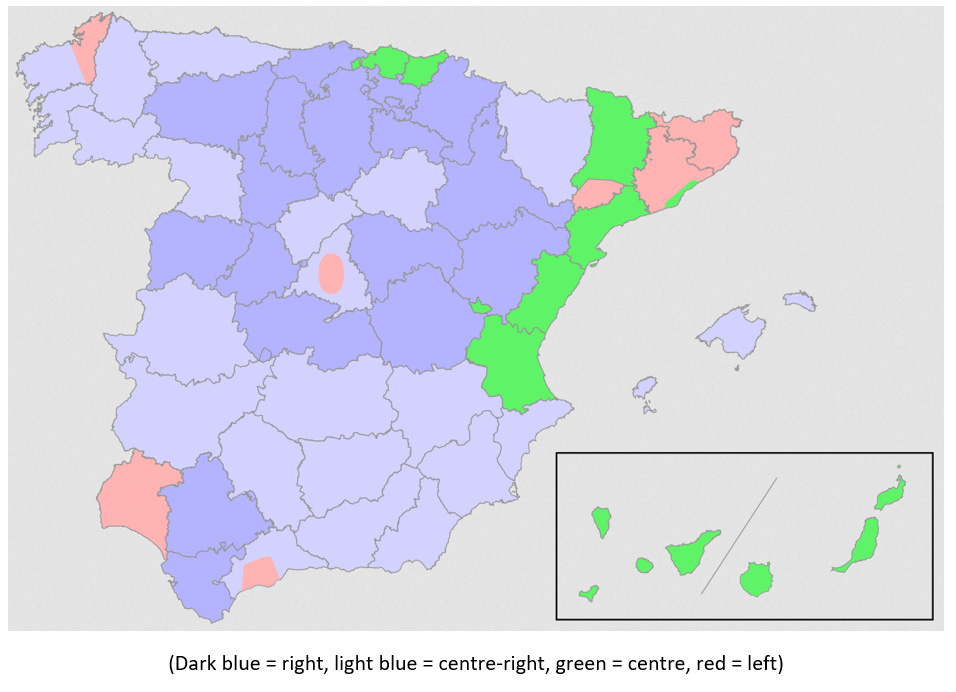

The 1933 General Election

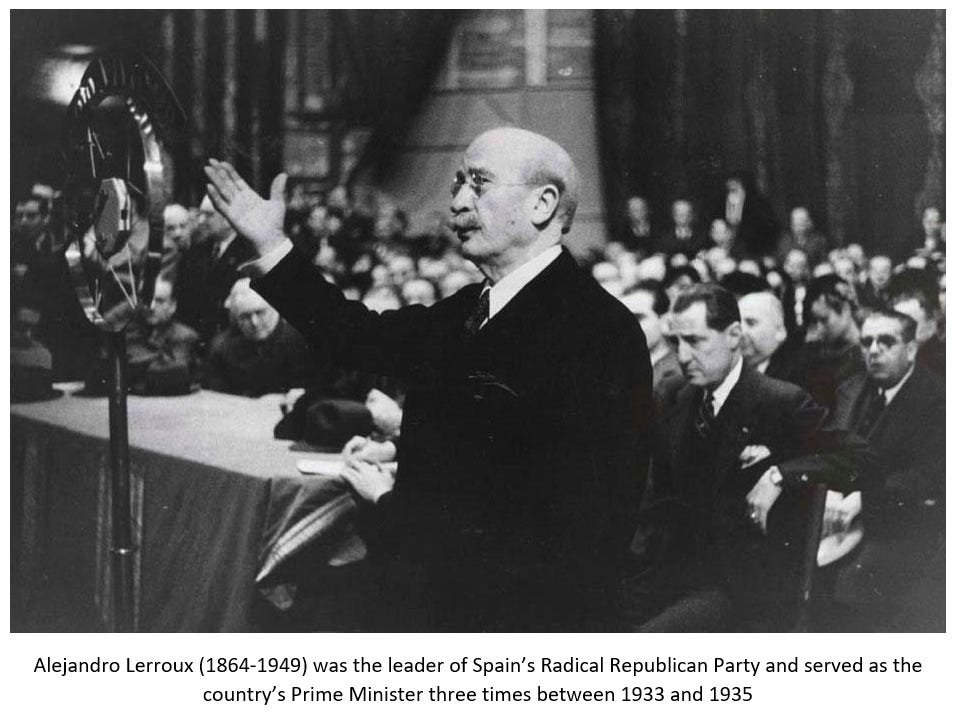

The withdrawal of the PSOE from government in October of 1933 forced new elections to be held one month later. PSOE’s gamble failed as it finished third, far behind both the Radical Republicans led by Alejandro Lerroux, and CEDA, a Catholic conservative-nationalist party led by José María Gil-Robles, founded earlier that year to represent a broad grouping of conservatives and right wingers opposed to what had occurred under the previous government.6 Ironically, they were helped in their victory by the female vote (women were granted the right to vote by the previous government)7, and by the abstention of the very large membership of the Anarchist trade union, the CNT.8

Shocked by the outcome, the PSOE not only rejected the results, but also issued legal challenges to overturn them, all of them failing to do so. As Stanley Payne describes:

This whole dismal maneuver revealed what had become the permanent position of the left under the Republic: they would accept only the permanent government of the left. Any election or government not dominated by the left was neither “Republican” nor “democratic,” a position that might well have the effect of making a democratic Republic impossible.9

Payne goes on to explain that despite taking part in the drafting of the Constitution of the Second Spanish Republic, it would go on to “flout legality ever more systematically, eventually reducing the legal order to shambles and setting the stage for the civil war”.10

“Centering the Republic”

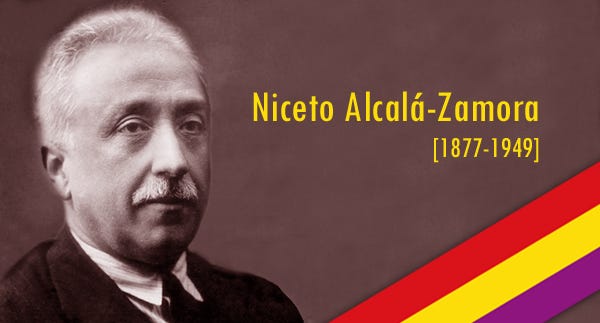

Despite the CEDA-led coalition winning the election, President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora did not invite them to form a new government. Instead, he called upon the leader of Radical Republicans, Alejandro Lerroux, to try and do so first. Alcalá-Zamora defended his strategy by explaining that he sought to “centre the republic”, meaning that he wanted a government built around a party that was totally committed to the republic and to parliamentary democracy. In his eyes (and with justification), there were too many non-democratic elements within the CEDA coalition. He also feared that a CEDA-led government would spark a rebellion by the PSOE and its labour union, the UGT.11 By offering first rights to form a government to Lerroux and his Radical Republicans, he was “strengthening” the democratic base of the Second Spanish Republic…at least in his own opinion. Pro-Republican historian Hugh Thomas on Alcalá Zamora’s difficult choice:

One added source of confusion was the distrust felt for both Lerroux and Gil Robles by President Alcalá Zamora, who intrigued against the former, and tried to avoid calling the latter to form a government. Alcalá distrusted Lerroux for his corruption, and Gil Robles as a secret monarchist. In the circumstances, he preferred Lerroux and, in fact, never called on Gil Robles: a weakening of the democratic process, since the Catholic leader was as prepared to work in a constitutional democracy as much as the socialists were.12

CEDA would have to wait almost a whole year before it was given ministerial seats in the ruling cabinet, and only because the government was threatened with collapse.

Alcalá-Zamora did what we did for mainly principled reasons, and within the power granted to him by the Spanish Constitution. Yet it did violate the spirit of democracy, leading to a further erosion of support for it. Making matters worse, he relied upon a politician and a party that had a reputation for corruption. The first year of of the new government was beset with corruption scandals and a government that could barely function as it required support from left republicans or CEDA to pass any legislation. CEDA did manage to undo the anti-clerical legislation that was passed in 1933 by the previous government via applying pressure to the shaky coalition that it was not yet a part of:

One of the non-republican right’s first objectives was to prevent the implementation of the Religious Confessions and Congregations Act, which had been passed in June 1933. And they got their way. Catholic schools continued operating normally, the government initiated talks with the Vatican to sign a new Concordat, and priests’ wages were partially reinstated: under a law passed on 4 April 1934, the State would pay two-thirds of the salary applicable in 1931 to priests over 40 years of age operating in small villages. The effects of this highly anticlerical law had been frozen, and religious displays, particularly rosaries and processions, were once again to be seen in many locations in Spain.13

Compounding matters for Lerroux, the Anarchists were at it once again:

Lerroux’s first difficulties derived from yet another series of anarchist challenges. They attacked isolated civil guard posts and derailed the Barcelona-Seville express, killing nineteen people. In Madrid, there was a long telephone strike. In both Valencia and Saragossa there were general strikes lasting for weeks. That at Saragossa, designed, to begin with, to free prisoners taken by the government the previous year, lasted indeed for fifty-seven days. The CNT never issued strike pay, but the workers’ resilience astonished the country. The anarchist leaders, as usual, for a time believed that they were in the anteroom of the millennium; and their pistolero friends heightened the drama by sporadic shooting.

……….

On 8 December, a revolutionary committee, led by Buenaventura Durruti, was installed at Saragossa. This fought for several days against the civil police, reinforced by the army, backed by tanks. Durruti became a national legend. In numerous places in Aragon and Catalonia, ‘libertarian communism’ was briefly established. Fighting occurred in many places, causing 87 dead, many wounded, and 700 imprisoned.14

This all happened PRIOR to CEDA entering the government. The Anarchists had unleashed anarchy against a centrist government that had nothing to do with conservatives and those further to the right. This was their third (!) violent rebellion in 1933 alone.

Lerroux finally threw in the towel and appointed three members of CEDA to cabinet positions on October 1, 1934. This led to a split in his own party, as it contained many secularists on its left wing that could not tolerate concessions to the Catholic Church that CEDA demanded more of. Those that rejected the inclusion of CEDA in the government immediately withdrew their support for it in the Cortes. It was at this point that all hell broke loose.

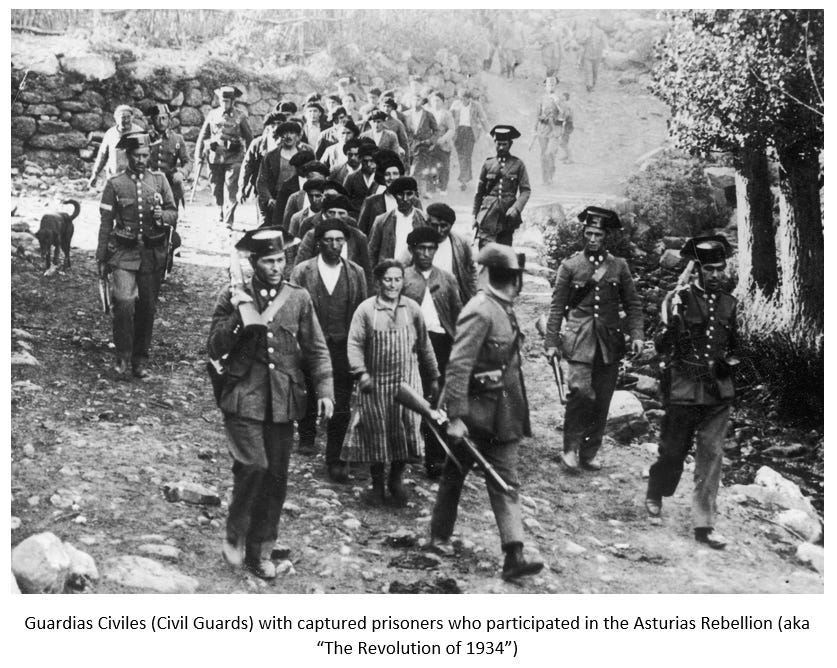

“The Revolution of 1934”

The Anarchists were opposed to any and all states based on their principles. The Socialists of the PSOE and their labour union, UGT, were opposed to any government that they did not lead, considering it both “illegitimate” and “undemocratic”. A Radical Republican-led centrist government was already being rocked by a series of violent anarchist uprisings and socialist-led general strikes, but a ruling coalition that contained CEDA meant that the Socialists too would have to launch an armed rebellion. Paul Preston, a British historian who is very supportive of the leftist forces in the Spanish Civil War, lays out the Socialist case for armed rebellion in 1934:

In the following two years, which came to be known as the bienio negro (black two years), Spanish politics were to be bitterly polarized. The November 1933 elections had given power to a right wing determined to avenge the injuries and indignities which it felt it had suffered during the period of the Constituent Cortes. This made conflict inevitable, since, if the workers and peasants had been driven to desperation by the inadequacy of the reforms of 1931–2, then a government set on destroying these reforms could only force them into violence. At the end of 1933, 12 per cent of Spain’s workforce was unemployed and in the south the figures were nearer 20 per cent. Employers and landowners celebrated the victory by cutting wages, sacking workers, evicting tenants and raising rents. Even before a new government had taken office, labour legislation was being blatantly ignored.15

Lerroux and his Radical Republicans as “puppets of CEDA”:

The President suspected the Catholic leader of nurturing more or less Fascist ambitions to establish an authoritarian, corporative state. Thus, Alejandro Lerroux, as leader of the second largest party, became Prime Minister. Dependent on CEDA votes, the Radicals were to be the CEDA’s puppets. In return for harsh social policies in the interests of the CEDA’s wealthy backers, the Radicals were to be allowed to enjoy the spoils of office. The Socialists were appalled. Largo Caballero was convinced that in the Radical Party there were those who, ‘if they have not been in jail, deserve to have been’. Once in government, they set up an office to organize the sale of state favours, monopolies, government procurement orders, licences and so on. The PSOE view was that the Radicals were hardly the appropriate defenders of the basic principles of the Republic against rightist assaults.16

The rapid radicalization of the Socialists ran in parallel to the same radicalization happening in CEDA. Gil-Robles did commit his party to constitutionalism and legalism, but he also did not keep secret his desire to change the Spanish Constitution once in power. Stanley Payne argues that CEDA sought to reform the constitution in order to protect property and religious rights, and to install a “corporative republic”, akin to the one in neighbouring Portugal, that was neither fascist nor an absolute monarchy.17 Gil-Robles did not help matters by flirting with fascist imagery during election campaigns and party rallies, nor did his more radical followers do anyone a favour by saluting him as “jefe” (leader).1819

By this point in time, everyone was accusing everyone else of ‘fascism’. Per Beevor:

Largo Caballero himself had acknowledged the previous year that there was no danger of fascism in Spain, yet in the summer of 1934 the rhetoric of the caballeristas took the opposite direction, crying fascist wolf–a tactic which risked becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.20

Payne:

One major focus for political violence was the danger of fascism. By 1933 it had become increasingly common for many different groups to call their opponents fascists. This practice was most indiscriminate among the Communists, who often called Socialists “social fascists” while also labeling the democratic Republic “fascist” or “fascistoid.” The liberal democrats of the Radical Party were termed “integral fascists.” The CNT repaid the Communists in their own coin, calling Stalinist Communism “fascist,” while also sometimes referring to “Republican fascism” and the “social fascism” of the Socialists. Some Catholics, in turn, had called the heavy-handed Azaña government “fascist.”21

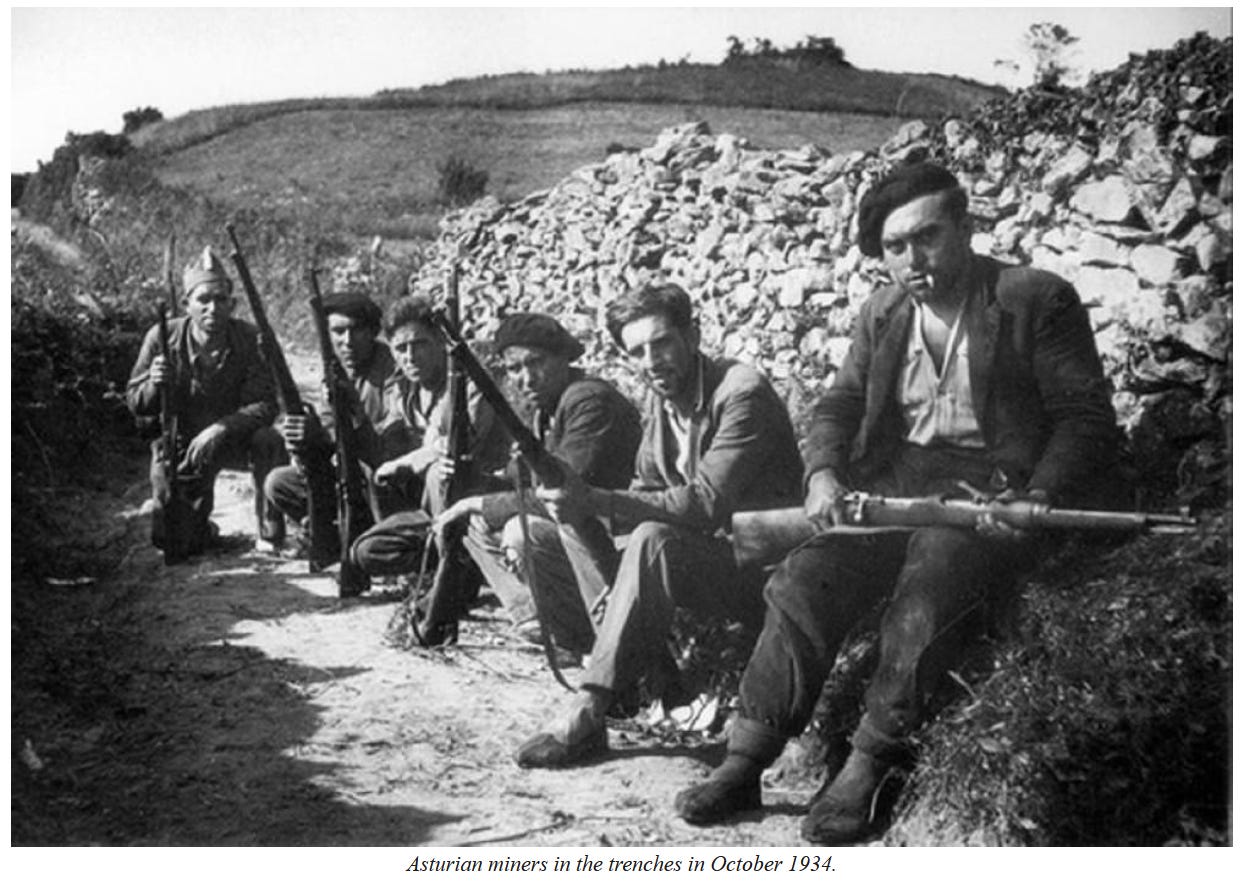

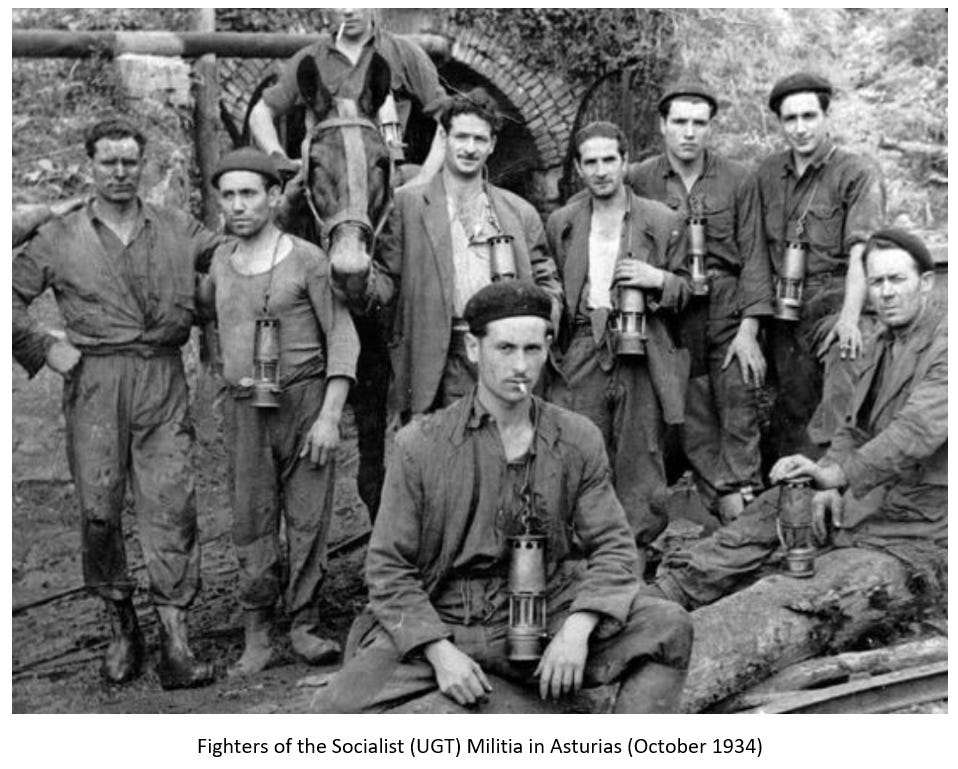

According to Julian Casanova, “nothing would be the same after October 1934”.22 The Socialists had already been preparing for an armed revolt for nine months by that point, with party chief Indalecio Prieto securing a large delivery of rifles and pistols that were received in a port just north of the Asturian capital, Oviedo.23

Gabriel Jackson describes what happened only days after CEDA was invited to join the government:

THE October revolution was intended to prevent the CEDA from participating in the government, a participation which appeared both to the middle-class liberals and to the revolutionary Left as equivalent to fascism in Spain. The revolt included three major phases. There was a series of uncoordinated and unsuccessful general strikes in the large cities on the fifth of October. Then on the sixth, Luis Companys proclaimed the "Republic of Catalonia within the Federal Republic of Spain" and invited a democratic "government in exile" to establish itself in Barcelona. Meanwhile, in the mining province of Oviedo the united proletarian forces began an armed struggle against the government, 'the Army, and the existing capitalist regime.24

The general strikes failed immediately25, as did the declaration of a “Catalan State”:

Despite the preparations for rebellion carried out by Josep Dencás, the conseller de Governació, General Domingo Batet, the head of the military garrison in Barcelona, ignored the orders given by Companys as the highest authority in Catalonia, and took over the city. In the early hours of the following day, he placed his troops outside the Generalitat building, and after limited resistance and artillery fire, the Catalan government surrendered. Miguel Badia, the head of the services of public order and a colleague of Dencás in the most radical sector of Catalan nationalism, tried to organise some sniper fire from roof terraces. When they saw that all was lost, Badia, Dencás and their military advisers escaped via a secret passage in the Cabinet Office, or via the sewers according to other sources, and fled to France. The fatal balance of the failed uprising was forty-six deaths, eight soldiers and thirty-eight civilians.26