The Future and Its Citizens

Demography, Mobility, Birth Rates, Migration, Economic Sorting, Inequality, Population Replacement, Death of Nations, City vs. Periphery

There’s a fantastic West German TV miniseries called “Heimat” (loosely translated as ‘homeland’) that was written, produced, and directed by Edgar Reitz and released in 1984. Over the course of eleven episodes, it chronicles the lives of the Simon family from 1919 until 1982. Set in the fictional village of Schabbach in the Hunsrück region of the Rhineland, we see how political currents, both national and international, and technology change not just where people live, but how they live and interact with the world around them as well.

The second episode is entitled "Die Mitte der Welt" (The Centre of the World) and covers the years stretching from 1929-1933. In the scene that gives the episode the title, one of the village brain trust explains to his circle of friends how Schabbach is at the centre by drawing a line in the ground to indicate that the same line that bifurcates the globe passes right through it. The intended symbolism of this act is to prove to the others that Schabbach is eternal and that their place in the world is guaranteed.

The fourth episode, "Reichshöhenstraße" (The Highway), takes place in 1938. The men in the village are excited about the construction of the Autobahn taking place just outside of the village, as it proves how the governing National-Socialists are modernizing Germany as promised. But one man points out how the highway bypasses Schabbach, symbolizing the village’s declining importance as time is about to pass it by as well.

I was lucky enough to watch this series as a young teen, and it has stayed with me ever since. If you can find it, check it out, as it’s well worth your time (especially the first 8 episodes that cover up to the arrival of the American occupiers after Germany’s WW2 defeat).

The reason why I bring up Heimat is that I read two articles earlier that discuss changing demographics, albeit in very differing ways and with differing focuses.

The first is a piece that appeared last week in the New York Review of Books that takes a look at Spain’s continually emptying countryside despite the rise in its overall population (thanks to a liberal immigration system). The piece, just like the publication, has a very liberal slant, and not only blames Franco for neglecting the countryside during the ‘Spanish Miracle’, but also places hopes that the purportedly non-partisan España Vaciada (Empty Spain) movement can be used to offset the swing to the right in places like the Castilian and Leonese countryside.

It’s no secret that much of western liberal democracy today is a fight between the capital (or larger cities) and the periphery. A cursory look at electoral maps over the years in western countries will quickly prove this. Urbanization has increased not just the size of city populations, but also their economic importance, political power, and their drawing ability. This has created an increasingly widening gulf between the city and the periphery to the point where they more and more resemble different countries. A classic example of this is Flyover Country vs. Coastal Elites who occupy key cities along the two edges of the USA.

Prior to the advances in health and medicine in the West that began in the mid-19th century, cities served as ‘population sinks’ due to its denizens both having lower birthrates than those in the countryside, and thanks to frequent outbreaks of plagues and illnesses that would decimate urban centres. Here in Dalmatia, it was common in the pre-modern era for plagues to wipe out 1/3rd or even half of a coastal city’s population every three generations or so. New arrivals from the countryside would replenish the populations of these cities over time.

The 21st century is a very different case; birth rates have collapsed across the West, and states are wholly reliant on mass immigration to maintain population and access to workers in these aging societies. This is a fix with all sorts of problems attached to it, from higher competition for employment, to wage suppression, cultural non-affinities, ethnic and racial conflict, and so on. Despite all of these issues, the present cohort of western elites sees no other way to overcome the demographic challenges brought on by the collapse in birth rates. Others welcome this development for their own personal (and often financial) interests.

Ideally, states should have a balanced population between country and city, but migrants are drawn heavily to already well-established population centres for various reasons such as employment prospects or proximity to relatives/people from their homeland, and so on. In Canada, immigrants will make a dash for Toronto or Vancouver, etc. once the first three years of their residency passes, leaving behind smaller centres such as St. John, Regina, and so on. In short, the countryside is doomed.

COVID-19 made us think of these issues in a different way. ‘Work-from-Home’ (WFH) led many people to realize just how much they didn’t like commuting long distances every work day, while others began to re-think whether it was worth living in an overpriced and tiny condo into your 40s. Is WFH a solution to re-balancing populations in western countries between city and countryside?

On the other hand, what is WFH suggests to corporations that plenty of their present staff can be made redundant and easily replaced by cheaper foreigners who can WFH in their countries? Is there movement towards this? Are people talking about this? I personally don’t know.

Strength in Numbers

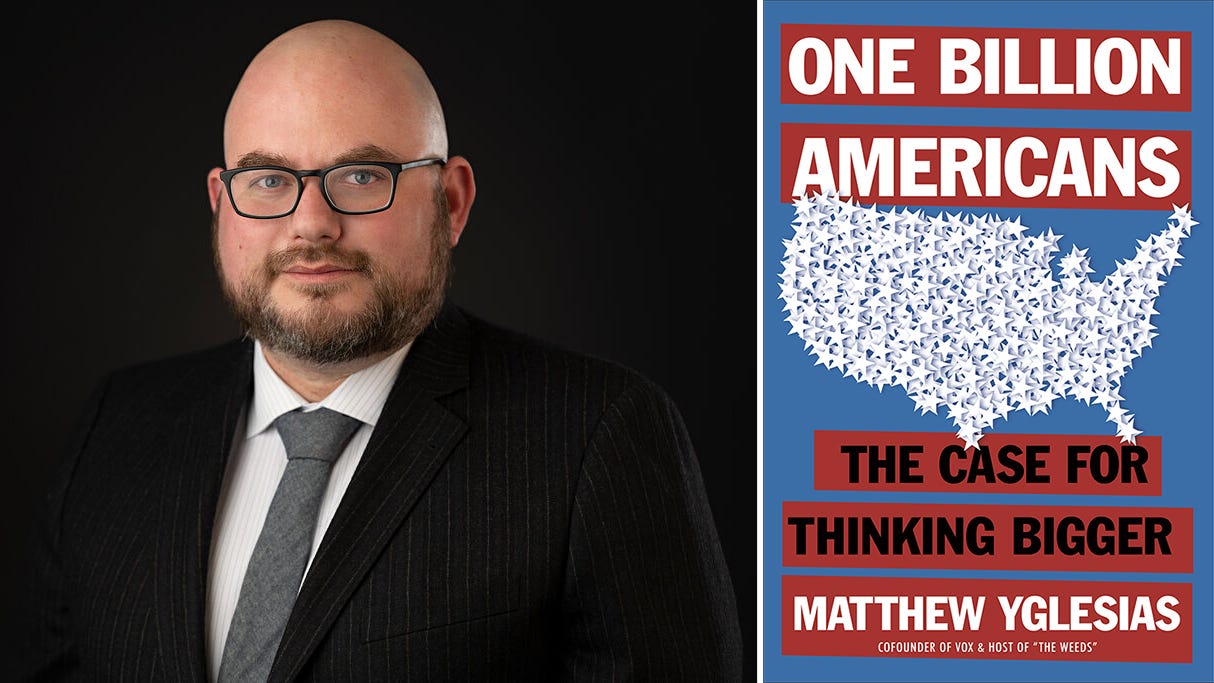

In “One Billion Americans”, Matty Yglesias lays out the case for growing the population of the USA in order to maintain its position as global leader.

Adam Van Buskirk takes this approach as valid and applies it to the entire world based on current economic, political, and demographic trends to divide the world into four different zones:

Metropole - rich and relatively young

Old World - rich and geriatric

Quiet World - older, economically stagnant

Young World - high fertility (at present), relatively poor

It’s the Metropole who Van Buskirk argues will lead the world for the foreseeable future, and that it can only strengthen its position over time by accepting young migrants from Young World to offset any negative changes in its demography. The Quiet World (Turkey, the Balkans, Eastern and Central Europe), will fade in importance, while the Old World (Western Europe/Japan/etc.) will become either a playground or museum for the more prominent Metropole.

Van Buskirk zones in on China’s aging population as a threat to its continued rise these past several decades, arguing that the USA can maintain pole position through mass immigration from Young World combined with appealing living standards aided by continued offshoring.

This is all very, very interesting stuff that will enrage many people who will conclude that Van Buskirk sees people as little more than economic units to be moved around the map. This is a valid criticism, but it does reflect how globalism idealizes the highly-mobile individual consumerbot as the best of all possible citizens.

Again, Van Buskirk is projecting outward based on current trends, one of which is the persistance of globalism, despite the world moving towards a bifurcation between a Chinese-led Eurasian+Africa bloc vs. The West+Japan/South Korea. If this division does cement itself, van Buskirk’s taxonomy will need a re-think.

But what if these trends do persist? What does this do to the idea of nation and of citizenship as well? And to repeat an earlier question: what is WFH serves to make migration unnecessary?

I'm not anti-capitalist or anything like this, but it seems self-evident that basing your economy and way of life on the idea of eternal expansion and growth is not only not sustainable, but insane.

Yes, I do think companies will use WFH to offshore white collar jobs.We need to keep in mind that many of these jobs are total bullshit. Why pay $100,000+ to some Yale Economics grad to work as an ESG consultant when you can pay $10,000 to a University of Mumbai Economics grad and get the same bullshit work done?

What I find is fascinating is how little this is being discussed. I remember in the early days of the pandemic, some reddit post bringing up the same exact dangers of WFH and he was downvoted into oblivion. To connect to your earlier piece, is it because we don't like alarmists?