Saturday Commentary and Review #78

Trudeau and Canada's Digital Outlaws, The ESG Deluge, Huntington Revisited in Ukraine, Russia's Powerless Oligarchs, When Texas Celebrated Big Boy Season

One of the great changes that I’ve experienced in my life is the intentional warping and degradation of the term ‘democracy’. When I was a young boy, democracy meant the freedom to choose who governed you and the freedoms attached to the concept of democracy, one of which included the freedom to think and say what you thought without fear of persecution.

Idyllic times, in retrospect.

Us Cold War kiddies had the luxury of living in a black and white world where we could point at the Eastern Bloc and mock them for how little political expression was allowed there. We may have not liked our own governments at times, but were free to protest them without fear of losing our livelihoods, so long as we weren’t engaged in overt violence or armed rebellion.

Bubbling under the surface of western liberal democracy was a newer trend that was authoritarian in nature. First called “Political Correctness”, it began to seep into the mainstream in the late 1980s where popular culture became the first battleground. This was only a first foray, and it was quickly fended off. “Freedom” was too ingrained in the Anglosphere consciousness to allow whining ninnies to upend it.

There’s no need to go into a description as to how it came back, how it seized and is seizing all of the west’s governing institutions, and so on. You all already know this, live this, and some of you have experienced their wrath personally. Nor is there a need to restate the concept of Popper’s Paradox of Tolerance, something that I have highlighted throughout the course of this Substack.

What does need to be restated is that democracy (which we wrongly mentally associate with “freedom”) has been redefined to be exclusionary rather than inclusionary, despite stated claims to the opposite. The confines of democracy are narrowed all the more as time goes by. To not adhere to the tenets of liberalism (in its three flavours: centrism, conservatism aka slightly-slower liberalization, and turbo liberalism aka authoritarianism) is to be left outside of the acceptable scope of democracy, meaning that you are anti-freedom at best and a Nazi at worst (unless you fight for the Azov Battalion in Ukraine). Authoritarian regimes like Saudi Arabia who fund NGOs in tandem with arms exporters and energy multinationals use these same NGOs as end runs around democracy, but if you protest at the scale of immigration that your country is engaged in, it’s you who is opposed to democracy.

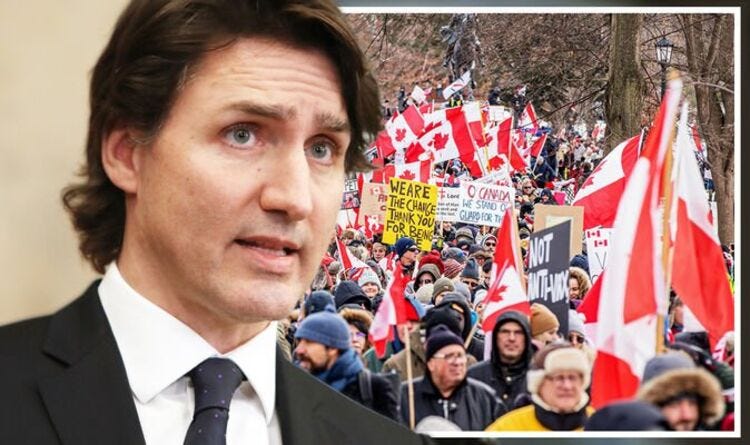

Besides the current war in Ukraine, the most important political development of 2022 so far has been the digital erasure of peaceful protesters in Canada by Justin Trudeau and his government. With a few keystrokes, Canadians have been completely locked out of the financial system in that country, a complete digital unpersoning. This renders them “digital outlaws” (outside of the law/protections under the law withdrawn, to apply it to the medieval case). Michael Young sounds the alarm.

What has changed? First, the old way:

In order to understand the problem that faces us now, we first need to understand two concepts: real-world friction and financial centralization.

To grasp the idea of real-world friction, let’s take the example of arresting, convicting, and jailing a citizen in a democracy. In order to make an arrest, a police officer must be hired and given the authority to make the arrest. He must locate the individual he needs to arrest. He must identify that individual. He must physically perform the arrest by placing handcuffs on the individual, and take him to a holding facility where he must read the arrestee his rights. As you can imagine, finding people and taking them to jail is a time-consuming, tedious, and difficult process.

Additionally, in order to prosecute the arrested person and carry out a judicial punishment, there must be a trial. The arrested person is entitled to a lawyer. It is required that evidence is provided and often that other people must testify. The accused is also entitled to a defense, and a verdict must be reached in his case. If the person is convicted, he must be taken to a jail cell. In short, a series of difficult steps must be taken in the real, physical world in order to arrest, convict, and jail someone.

The new way:

In the world we live in now, an increasing number of financial transactions are done digitally. We get email approval for mortgages, we have apps on our phones that deliver our financial information in real time, we make purchases using interbank networks, we buy products online, and we place orders over the internet with PayPal and other e-transfers. Each of these transactions leaves a digital trail of information that can be saved and stored easily and forever. With ever more processing power, the ability of large institutions to organize this data and make it searchable is becoming easier, making it possible for third parties and institutions to track what everyone does with their money. It’s no longer necessary to spend large amounts of time and manpower pouring over paper receipts to figure out how a business or individual spent their money.

Moreover, the world’s various financial institutions are becoming increasingly interconnected and enmeshed. They use similar technologies, are connected to similar networks, have data sharing agreements of various kinds, and more often now, financial institutions use common digital infrastructure. The decentralization that was the norm in a cash society has eroded. The financial world is quickly becoming centralized as the major players become ever more interconnected.

The loss of real-world friction coupled with the increasing centralization of the financial system has opened up possibilities for new forms of coercion, control, and power—particularly when governments and the private sector decide to cooperate. Which brings us to the case of the Canadian prime minister.

The incredible ease with which governments can now create digital outlaws, unpersoning its own citizenry:

To express opposition to certain COVID policies in Canada, a group of truckers decided to hold large, nonviolent public protests that began at the end of January. As part of these protests, they decided to block a number of roads and bridges, many of which were important for commerce and trade. Semitrucks are very large, very heavy, and require specialized equipment to tow in the event a driver refuses to move his or her vehicle. In this case, the government was either unwilling or unable to get the specialized equipment required to move the semis in a timely manner. So the Canadian federal government decided to exercise financial pressure in order to convince the truckers to move. In doing so, Trudeau and his government exercised a form of power unprecedented for a democracy.

The Trudeau government declared a state of emergency, and using its emergency powers began to freeze the bank accounts of anyone they had reason to believe was blocking roads and bridges—including not just the truckers and other protesters themselves, but those who financially supported them. Rather than having to go through the very difficult task of physically moving semitrucks, and fining, ticketing, or charging those who blocked bridges and roads, the government gave a simple order—and with a few keystrokes, people associated with the protest were almost completely locked out of Canada’s financial system. Everything from paying mortgages, to buying gas, to getting a cup of coffee at a drive-thru became impossible for those that the government had deemed to be a problem.

What happens when a government is no longer required to do the very difficult, friction-filled work of finding people, writing tickets, arresting them, charging them, granting them due process, obtaining convictions, and jailing the guilty? When the government can bring a person’s practical participation in society to a standstill with the push of a button, it becomes silly to even talk about individual rights or due process. In the face of this new kind of push-button power, exercised at the whim of the governing party with zero legal oversight, individuals can simply be deleted from the system—even if, technically speaking, they are never charged with or convicted of a crime.

Canada has crossed the rubicon, or, to use another phrase, it has let the genie out of the bottle. We all know how power hungry government officials and those in the private sector are, so what is stopping this from proliferating?

And this brings us back to the concepts of freedom and democracy: Trudeau’s overreach erodes those liberal values. There is no doubt whatsoever that the west has taken an authoritarian turn. That makes the notion that it is fighting on behalf of ‘democracy’ against authoritarianism all the more ridiculous.

The genius of the USA is its ability to co-opt anything and turn it into profit. I recall comedian Denis Leary in his standup special “No Cure for Cancer” explaining this concept perfectly when describing how McDonald’s managed to turn that tradition of France, the croissant, into a Croissandwich. He was 100% right.

It’s this ability to co-opt and monetize anything that is where America excels in the world, leaving all others in the dust. It is also precisely this which creates the room for the private sector to buy into new ideas and concepts that are pushed from places like government or academia.

I bring this up because the private sector has now bought into the new, more narrowly-defined concept of western liberal democracy through what is known as ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance). Ideally, this new trend in corporate investment steers business towards environmental and social responsibility, and pursues inclusive governance to guide to those first two principles while addressing historical grievances. In short, if you’re a “fat, black, crippled dyke”, your time has come to cash in (watch this video from circa 1990 to get the reference. They were way ahead of their time).

ESG is all the rage in the investment community now, especially after it has received huge, public backing from that titan of investing, BlackRock (they manage around $10 Trillion (!) USD in investments). It is inescapable, and it soon will become standardized across the business world in the west….and contrary to logic, it is also incredibly profitable, as Ron Ivey explains:

On what ESG actually is:

ESG—environmental, social, and governance—investing has become one of the fastest growing areas of finance in recent years and increasingly influences capital allocation decisions for investors and firms. But what exactly is ESG, and does its actual impact on a broad group of economic “stakeholders” match its advertising? As ESG funds have grown their assets under management in recent years, ESG investment criteria have, if anything, only become more contested.

Indeed, Bloomberg Businessweek recently revealed that the largest for‑profit accreditation company of corporate environmental and social responsibility, MSCI, does not actually measure a corporation’s impact on society or the environment, but rather assesses how companies are reducing regulatory and brand risks for their shareholders.1 New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran recently lamented that the ESG ecosystem is merely a “gravy train” for consultants, ESG fund managers, and investment marketers, leading to little social benefit for stakeholders outside of the self-serving circle of the ESG industry.2 Former Facebook executive, SPAC promoter, and Social Capital founder Chamath Palihapitiya has made an even bolder statement that ESG funds and evaluation agencies like MSCI are fraudulent products.3 He argues that these groups use the veneer of social and environmental responsibility to reduce regulatory oversight for multinational behemoths while allowing them to apply for negative interest rate loans from central banks. From Palihapitiya’s perspective as a venture investor, these “green washed” and “social washed” funds attract investment away from actual businesses that are addressing social and ecological challenges more fundamentally in their business models.

A booming industry:

Nevertheless, whether the ESG industry is a gravy train, a fraudulent system of smoke and mirrors, or a mixed bag of confusing options, one thing is clear: the industry is ballooning. By 2025, ESG funds are predicted to grow to $53 trillion.6 One in three dollars invested globally is now invested in ESG products.7 From 1993 to 2017, ESG reporting grew from 12 percent to 75 percent in the hundred largest corporations in forty-nine countries (4,900 companies).8 By some estimates, there are 160 ESG ratings and data products providers worldwide.9 Fueling this growth is increasing demand from investors across all demographics. According to a survey conducted by Natixis Investment Managers of 8,550 individual investors across twenty-four countries in April 2021, 77 percent believe it is their responsibility to keep companies accountable for their impact on society and the planet.

And yes, just as you assumed, it is largely bullshit:

Yet paradoxically, ESG funds rarely vote in favor of environmentally and socially conscious shareholder resolutions.11 Researchers assessed 593 equity funds with over $265 billion in total net assets that specifically used ESG- and climate-related key words in their marketing. They discovered that 421 of the funds, or 71 percent, have a negative “Portfolio Paris Alignment” score, indicating that the companies within their portfolios are misaligned from global carbon reduction targets.12 BlackRock’s U.S. Carbon Transition Readiness ETF has holdings in fossil fuel companies and invests in the largest funder of fossil fuel companies, JPMorgan Chase.13 Institutional Investor magazine has highlighted a litany of examples of major brands (Coke, Nestle, etc.) that have been celebrated as ESG stars and yet deplete local water aquifers, generate significant plastic waste, employ child labor in their supply chains, and provide mostly unhealthy beverages to their customers that contribute to obesity, diabetes, and other health problems.14 Other highly rated ESG investments like Nike, HP, and Salesforce have used accounting tricks to avoid paying U.S. taxes.

ESG is how the business world manages to reduce corporate brand risk and promote the elite-driven social changes that infiltrated popular culture and government with its roots in academia, while turning a nice profit and employing all those consultants that have been overproduced in western schooling. A nice public-private partnership that is unbeatable. The kids call this a ‘blackpill’.

I’d rather not spend too much time on the current war in Ukraine simply because the Fog of War is in effect. This is made all the worse by the complete distortion of the facts on the ground by the torrent of western propaganda and misinformation. It is best practice to watch and observe and take no sides’ statements as anything resembling fact.

This conflict is characterized by western leaders as a fight between democracy and autocracy. All my readers know that this is bullshit.

This conflict is characterized by some Russians as the restoration of the Russianness of Ukraine. That is also bullshit.

This conflict is about the existential threat posed to Russia by NATO expansion in Ukraine, whether actual or stealth. That’s it. All else is bullshit, but various justifications are stated for public consumption and buy in.

Ukraine, thanks to its division between its primarily Orthodox centre and east and its (Byzantine) Catholic West, formerly Habsburg, is a ‘cleft’ country. The “West” has expanded into the “East”, and has captured the centre of the country and parts of the east. Zbigniew Brzezinski viewed Ukraine as the ultimate prize to be snatched from Russia’s grasp, as it would render Russia an Asian power instead of a Eurasian (and by extension, global) power.

The Catholic/Orthodox divide was one highlighted by Samuel P. Huntington in his “The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order”, a seminal book that has influenced geopolitics ever since. In it, he posited that the future of conflict would be civilizational rather than ideological, as it would pit civilizations against one another. He divided the Orthodox East from the Catholic and Protestant West. The great Christopher Caldwell revisits his thesis and applies it to the current conflict in Ukraine:

In late March, Volodymyr Omelyan, the former Ukrainian minister of infrastructure, went on NPR to denounce a “clash of civilizations” now underway. On one side, as Omelyan saw it, was Ukraine, which only wants “democracy,” “progress” and “development.” On the other was Russia, which wants “to occupy, to destroy, and to kill”.

What Omelyan is describing is a clash of Good and Evil. Whether you think of the Russia-Ukraine conflict this way depends on which side you are on. But whatever you call it, it isn’t a clash of civilizations. In fact, it is almost the opposite of what the late Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington meant when he brought the phrase “clash of civilizations” into common parlance with an article in Foreign Affairs in 1993.

Context:

The ideological struggles that had pitted Communists against anti-Communists for 75 years were on their way out. The new struggles, he wrote, would pit seven or eight cultural areas against one another: “Western, Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic-Orthodox, Latin American, and possibly African.” Huntington spent the years until his death in 2008 as a partisan in these struggles, urging the United States to recognize—and safeguard—the “Anglo-Protestant” cultural traits that had given America the upper hand.

The clash-of-civilizations model proved spectacularly useful for making predictions. Huntington produced a detailed map of one civilizational border that seemed to explain everything: the line where Western Christianity met the Orthodox and Muslim worlds 500 years ago, on the eve of the Reformation. In 1993, that line was a battle line, as post-Communist Yugoslavia collapsed. It is a battle line today: Follow it north, and you will pass through the middle of Ukraine.

Demographic booms as a driver of conflict:

While all civilizations go through cycles of quiescence and belligerence, these are frequently determined by non-civilizational factors, especially demographics. Pious, purity-obsessed Islam was the clashing civilization par excellence at the turn of this century, and almost all the claims of its political radicals were made in civilizational terms. But a big part of the problem, as Huntington saw clearly at the time, was a population explosion that had been going on for a generation. The Arab world had produced a glut of military-age sons, and offered them precious few avenues to wealth and social standing. Some sought glory as mujahideen or suicide bombers.

The shrewd sociologist Gunnar Heinsohn went further. He speculated that Islamic fundamentalism, while sincerely asserted, might be a red herring. The residents of the Palestinian territories, for instance, were not the most religious people in Muslim lands. But in barely a generation after 1967, the population of the West Bank and Gaza bulged to 3.3 million, from 450,000. Bombings proliferated. When this wave of men passed from youth into sedentary middle age, however, the problem of terrorism mostly passed with them.

By the middle of this century, the population of Africa will double, adding roughly 1.2 billion young people to a straitened economy. Heinsohn and Huntington would predict violence as a result. When it comes, grandiose civilizational claims will be made by those who commit it. But that will not mean it has a wholly civilizational cause.

What is unfamiliar, in Huntingtonian terms, about the Russia-Ukraine conflict is that it is being fought by two countries that are demographically stagnant. Aggression has not resulted from the friction of two over-dynamic and overpopulated civilizations, but has been drawn into a civilizational vacuum.

America as always siding with the less familiar rather than the more familiar:

Huntington had a traditional idea of what a civilization is and how to maintain one: by protecting its borders, its language, and its social structure. But over the past generation, not a single effective US president has agreed. Washington has aggressively policed the international order it established at the end of the Cold War. But this order treats civilizations as if they are vulgar, not to be spoken of—you might even say uncivilized. Maybe America’s deep liberal roots led it to see most civilizational institutions as constraints, as insults to the idea that all men are created equal, as obstacles to human flourishing. Maybe the more recent American commitment to civil rights—which brings an instinct for backing underdogs—was misapplied in other, foreign contexts.

For whatever reason, the United States frequently sides with the more civilizationally distant of two warring civilizations: with the colonial world against Europe in the late 1940s, with Egypt against France and Britain in 1956, with Pakistan against India in 1971. It sides with its enemies against its rivals. In the Balkans in 1998, it rallied along with various jihadists to back Kosovo against Serbia, an episode that left an enduring mark on Russian attitudes towards the West. The immediate reaction of George W. Bush to the 9/11 attacks was to declare: “Islam is peace.” For a considerable number of people inside and outside our civilization, the result has been confusion.

Ukraine as running counter to Huntington’s thesis:

Huntington paid especially close attention to the rivalry between post-Cold War Russia and post-Cold War Ukraine. He noted the Crimean parliament’s 1992 declaration of independence from Ukraine, and speculated that Ukrain might split politically into Russian and non-Russian halves. They had plenty to fight over: Crimea, the Soviet Union’s Black Sea fleet, and nuclear weapons. But this was a rare instance when Huntington explicitly ruled out a clash of civilizations. “If civilization is what counts,” he wrote, “the likelihood of violence between Ukrainians and Russians should be low. They are two Slavic, primarily Orthodox peoples who have had close relationships with each other for centuries.” Huntington called this “civilizational rallying” and suggested that the West could use it “to promote and maintain cooperative relations with Russia and Japan.

Huntington’s failure regarding Ukraine might be do to what Caldwell suggests is his overcomplexity; it can be reduced to hegemon vs. revisionist, another concept in the study of geopolitics.

Long-time readers of my Substack will have read what I have written on the disastrous 1990s in Russia, when a drunken Boris Yeltsin handed over the keys to Russia to a coterie of ruthless “businessmen” who proceeded to steal everything, nailed down or not, pilfering the country with the assistance of western financial interests. This gave birth the to the Oligarchy, which was the actual power in Russia, until the arrival of Vladimir Putin as President.

One of the first things that Putin did in office was to organize a meeting with the Oligarchy in which he offered them a new deal: give up your political power and I won’t throw you in jail. You can keep your wealth and your companies. Some took the deal, some didn’t. Boris Berezovsky didn’t, and went into exile where he plotted with the UK’s MI6 and the USA’s CIA to overthrow Putin. Mikhail Khodorkovsky tried to take on Putin directly in Russia, and ended up first in prison, then in exile. From exile he continues to fund efforts to overthrow Putin.

Mikhail Fridman of Alfa Group was one of those who took the deal and flourished in Putin’s Russia. His realm was business, not politics. Last week, he informed Bloomberg that all western attempts to try to get him and other business leaders to turn against Putin and overthrow him were pointless, because they were rendered politically powerless by Putin.

What’s clear to him now, he says, is that the EU doesn’t get how power actually works in Russia. If the point of sanctions is to motivate people like him to apply pressure on Vladimir Putin, he says, that’s worse than unrealistic.

“I’ve never been in any state company or state position,” Fridman says. “If the people who are in charge in the EU believe that because of sanctions, I could approach Mr. Putin and tell him to stop the war, and it will work, then I’m afraid we’re all in big trouble. That means those who are making this decision understand nothing about how Russia works. And that’s dangerous for the future.”

A funny aside:

Fridman was worth about $14 billion before the war, according to Bloomberg. He’s now worth about $10 billion on paper and is in the strange position of being an oligarch with essentially no cash. When the U.K. followed the EU and sanctioned Fridman on March 15, his last working bank card in the U.K. was frozen. He tells me he now must apply for a license to spend money, and the British government will determine if any request is “reasonable.” It appears that this will mean an allowance of roughly £2,500 a month. He’s exasperated, but careful not to compare his woes with those of Ukrainians suffering from the war. “My problems are really nothing compared with their problems,” he says.

“Oi! Do you have a loicense for that?”

The uselessness of sanctioning the already politically weak oligarchs:

“It’s an indirect approach, with one of the strategies being that if the oligarchs close to Putin are being pressured, they will pressure Putin,” says Adam Smith, a partner at the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and a former senior U.S. Department of the Treasury official who advised on sanctions from 2010 to 2015. “The U.S. sanctioned oligarchs before—starting in 2014 and then several in 2018—and the success of that strategy is spotty, both in terms of whether the oligarchs stopped supporting Putin and whether they were harmed.”

Even so, the sanctions imposed so far look scattershot—some hits, some misses, and some mere scrapes. The U.S. hasn’t sanctioned Fridman, Aven, or their partner German Khan. The EU sanctioned Fridman and Aven as individuals, but the U.S. and EU have imposed only light restrictions on Alfa-Bank, which generated much of their wealth. Other inconsistencies jump out. The U.S., the U.K., and the EU sanctioned Alisher Usmanov; he’s blocked from accessing his yacht and private jet, but the U.S. immediately turned around and gave licenses to allow some of his companies to continue doing business. A number of high-profile targets have dodged restrictions. State-controlled Gazprombank has largely remained untouched because of its central role in Europe’s gas trade.

Fridman’s argument that he’s not positioned to exercise influence over the Kremlin reflects how the role of Russia’s billionaires has been turned on its head since the 1990s. Back then, Fridman was one of the original seven oligarchs, the semibankirschina. As a group they backed President Boris Yeltsin’s reelection campaign and had sway over the Kremlin. When Putin came to power in 2000, he imposed his own model: The new deal was that if they stayed out of politics, they could continue running their businesses. Putin destroyed oligarchs who violated that arrangement, most notably Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who spent 10 years in jail after he tried to get into politics. In his 22 years in power, Putin has helped create a new crop of oligarchs, who have grown rich from state contracts and running state-controlled companies.

US over-reliance on sanctions is the proverbial hammer that sees everything as a nail.

We end this week’s Substack with some heavy fare: when Texas used to celebrate Big Boys.

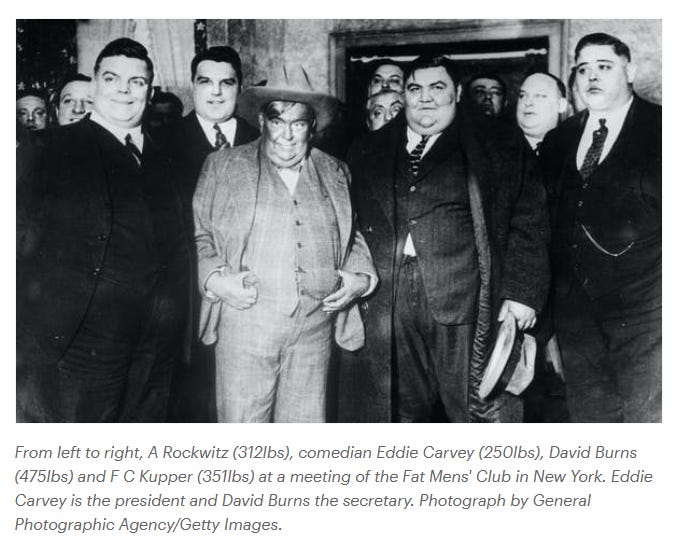

“Reckhart is Fasting” read the headline of a 1902 El Paso Daily Times. Reckhart, apparently, was “eating only one 15-cent meal a day” so that he could gorge himself at an upcoming party. And not just any party—this was the fat men’s club’s so-called “foolisher.” The foolisher committee, however, had great anxiety about food and drink holding out if Reckhart were to arrive at the festivities with his sizable belly completely empty. To avoid such calamity, the club members were “seriously contemplating holding a courtmartial.” They informed Reckhart that if he expected to come to the party they wanted him at least “partly fed.”

This is one example of the many curious troubles and happenings in the history of Texas’s fat men’s clubs. From the late 1800s to the mid-1920s, fat men’s clubs flourished widely across the state. To enter, members had to be a minimum of 200 pounds, and turn over at least $1 (the equivalence of about $25 today). The clubs’ purpose? According to an address by the president of the budding Fat Men’s Association of Texas, W.A, Disborough, the goal was “to draw the fat men into closer fraternal relations.”

The social clubs had calendars as packed as their plates. They networked at balls, sports events, and banqueting, and before many of the events, they held competitive weigh-ins where the largest members heralded their size. (At El Paso’s Annual Picnic of the Fat Men, the infamous Mr. Reckhart was the top tipper of the scales at their pre-barbecue weigh-in.) Men were so invested in the outcome of club weigh-ins that they were prone to cheating by stuffing weights in their pockets, as the Weatherford fat men’s club was reported to have done before a 1920 baseball game. According to Kerry Segrave’s Obesity in America: 1850-1939: A History of Social Attitudes and Treatment, one fat men’s club in Ohio used the weigh-ins to decide their club’s next president, and whoever sent the scales’ numbers flying highest immediately earned the honor.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries definitions of and attitudes about fat bodies were remarkably different than they are now. What qualified a man for a fraternal order of fat men in 1890, today, is now a mere four pounds over the average male size in America. But as fat men’s clubs were at their peak, people positively associated men of a larger size with wealth and affability. The members of Texas’s fat men’s clubs certainly were not pinching pennies, and the list of member occupations included assayers involved in gold mining, railroad presidents, successful butchers, and liquor dealers.

Men of large girth were also thought to be a kinder, more sociable sort than those without meat on their bones. The Mineola Monitor ran an op-ed in 1899 about why women should like fat men: “It may be observed, without intentional offence [sic] to any young lady who might be enamored of some skeleton-like young man that, as a rule, fat men, besides being the most jolly and convivial of the male species, are also apt to be the most considerate of and charitable to others.” The column concluded: “The fact still remains that seven out of ten fat men make excellent husbands.”

Funny shit.

Thank you for once again checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share it across social media. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you and don't forget to subscribe if you haven't already.

I think ESG serves (at least) two purposes.

One, it allows “passive” fund management companies like Blackrock an excuse to interfere in the operations of institutions they own a stake in. They need an extraordinary excuse because they are supposed to be passive - this excuse is ESG. So they can say, “you’re not against Blackrock promoting a healthy environment, sustainable societies and good governance, are you?” And so now they have their excuse to interfere.

The second is that it provides a smokescreen for coordination between policymakers and financiers. The public can see the two groups working together, so when accused of making corrupt bargains, ESG allows one to say “no no no, we’re just working together to save the environment”.

As always, by settling on a consistent narrative, it makes everyone’s activities much easier to coordinate and makes sure everyone gets the wording right when speaking to the public.

Another example of “Mercurialism”. Nothing is ever what it says on the tin…

I realized recently that much of what is happening is that the US is being turned into 1990s Russia. It’s even the same group of people involved. No wonder they are no fan of Mr. Putin.