Saturday Commentary and Review #182

Europe's Annus Horribilis, Biden Team: "USA in a very strong global position", Georgia's ex-President Throws in the Towel, "Stop Blaming Foucault", The Genius of Kubrick

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

This is the last SCR of 2024, and we’re going to make it a much shorter one than usual for two reasons: 1) the content isn’t new to the readership here and 2) there is always a drop off in media production around this time of year. Looking towards 2025, I am going to have to cast an even wider net to find good essays/articles/reviews/etc., as it is getting more and more difficult to do so thanks to the shutting down of online outlets combined with de-boosting of foreign links at places like Twitter/X, once the greatest of all news and articles aggregators around. The great Helen Andrews has also lamented this development. I will make it work, though. There is also a third reason as to why this one will be shorter than usual: most everyone is enjoying the Holiday Season (as they should!).

We’ll start off this last 2024 SCR with some cheer and merriment; Europe had a terrible year, and it’s probably going to get worse:

Europe’s growing far right, meanwhile, has only entrenched its position. This summer’s European elections were marked by breakout performances for the hard right across the union, and there were major advances on the national level, too. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom forged a government coalition; Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s post-fascist prime minister, saw her popularity deepen; and the far-right Alternative for Germany surged to become the country’s second-most-popular party.

Europe’s extreme right has moved past the point of normalization — now a regular force of government, it is becoming almost banal. For Europe, its consolidation caps a year of tumult. Judging from the continent’s parlous economic situation and general social disarray, matters are only going to get worse.

This is from the New York Times, and one of the authors, Anton Jaeger, is a left-wing academic (and mutual of mine on Twitter/X), so keep this in mind as you read it.

A decade ago, Europe presented a very different face to the world. In Greece, the radical left party Syriza was about to rise to power on the back of resistance to austerity imposed by the so-called Troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank and the Eurogroup. In France, a center-left president, François Hollande, was being hounded by rebels on the left of his party. And in Britain, a socialist backbencher named Jeremy Corbyn was soon to claim the leadership of the Labour Party.

All of this reads like ancient history today. Syriza, which ultimately carried out the austerity it had campaigned against, lost power in 2019 and splintered after a former Goldman Sachs trader was elected as its leader. Mr. Corbyn has been kicked out of the party he once led, and the French left has been sidelined by Mr. Macron’s penchant for cutting deals with the right. Die Linke, once a credible challenger to the Greens and Social Democrats for leadership on the German left, risks disappearing from parliament altogether in the country’s upcoming elections.

The Euroleft has a habit of blaming austerity for the decline in the fortunes of the continent’s left wing parties. They feel that they were guilty of compromising too much, or straight up collaborating with what they refer to as “neo-liberal” forces:

This decline is not the result of a political law of nature. Instead, Europe’s current political constellation owes much to a cohort of politicians and officials who held sway in the 2010s across the continent. Following Angela Merkel’s lead during her 16-year stint as Germany’s chancellor, it was they who set the terms of European politics that have now come back to haunt policymakers. Their response, for instance, to the “euro crisis” — the seemingly never-ending financial troubles that followed the crash of 2008 — was to offer a damaging blend of moralism and technocracy.

Doubling down on punitive austerity measures, Jeroen Dijsselbloem — Ms. Merkel’s lieutenant as head of an informal grouping of Eurozone finance ministers — claimed that the debt-ridden governments of Southern Europe had wasted their money on “schnapps and women.” For his part, Jean-Claude Juncker, then chief of the European Commission, admonished Greeks that there was “no need to commit suicide because you are afraid of dying.” Led by Ms. Merkel, Europe’s politicians insisted on obeisance to financial markets and European etiquette, no matter the consequences.

A collapsing economic model and a stagnant Europe:

Today, the costs of this aggressive aversion to change have become starkly apparent. In the past decade and a half, continental growth indicators have gone from stagnant to concerning. In a recent X-ray of the European economy, Mario Draghi, a former head of the European Central Bank and former prime minister of Italy, sounded a belated alarm as to the grim extent of the decline: lack of innovation, lagging productivity and general economic underperformance. The continent’s economic future looks impossibly bleak.

The wallop has been a long time coming. Occupied with disciplining Europe’s periphery, policymakers in Berlin missed a reckoning with Germany’s economic model. A book published this year by the German commentator Wolfgang Münchau required no more than two syllables to sum up the results of this procrastination: “Kaput.” Mr. Münchau’s list of causes for the downturn are familiar: the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which together spurred a global price fever and cut off the usual source of energy on which German factories ran — an inflationary spiral compounded by America’s trade wars. For an economy coasting by, these shocks proved worse than destabilizing.

Germany’s prized export sector especially suffered from such complacency. For years, reports of an impending green revolution in electric vehicle production were dismissed. Now an industrial doomsday is dawning: Germany’s car producers have seen themselves priced out of their trusty Chinese markets, steadily served by Chinese producers. As catastrophic growth forecasts told a story of their own in October, Volkswagen announced it was closing factories in Germany for the first time in its 87-year history, with severe knock-on effects for neighboring economies in Belgium, Poland and the Netherlands.

Those who find themselves on the political right will have many problems with characterizations of the following excerpt:

Economically, the Merkel consensus sowed the seeds of stagnation. Politically, it wound up destroying dissidence to its left while allowing discontent on the right to thrive. As inflation pushes the cost of living skyward and real wages stagnate, European electorates have been left with the sense that the levers of policy are slipping from their grasp. Railing against immigration — long a source of ire for many across the Western world — and engaging in Americanized culture wars at least allow a cathartic release and the illusion of control.

In this environment, far-right forces have predictably prospered, alternately tolerated and co-opted by the political center. In seven out of 27 countries in the European Union, from Finland to Italy, the far right now directly participates in government. In the newly assembled European Commission led by Ursula von der Leyen, a key ally of Ms. Meloni holds an important vice-presidential position. Rather than the bloc fending off the far right, the prospect seems to be a far-right European Union, in which the mainstream chases the extremes.

Two issues will dominate the European continent in 2025:

how to achieve a peace deal in Ukraine and re-start much-needed trade with Russia (US-permitting)

how European leaders at the EU and national levels approach the return of Donald Trump to the White House

Europe is in danger of playing second fiddle on the first point and fumbling the second one. I wouldn’t expect much different from this uninspiring lot.

Turbo America had a very, very good 2024, as the Americans continued to poke The Bear in Ukraine, deftly manage Israel’s tactical victories over Hezbollah and Iran (while keeping a tighter lid on Hamas), and monitoring the removal of the Syrian rook from the geopolitical chess board. It’s only China and East Asia where the USA have not continued to rack up the Ws.

Biden’s National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, is chuffed. He insists that his team’s work means that Trump is inhering a very strong global position to begin his new administration:

“I think what we’re handing off is a very strong hand from the United States in terms of our national power, in terms of the strength of our alliances, and in terms of a key point that you made in your opening statement, which is that America’s competitors and adversaries are weaker and under greater pressure than they have been.”

He added: “I’m proud of what we’re handing off.”

One important idea where the American position has improved during the last four years is in military preparedness, Sullivan said.

“America’s defense industrial base was in an incredibly weakened state,” he said, saying it was a decline “40 years in the making.”

Iran certainly is in a much weaker position than 4 years ago, with 40 years of its foreign policy going up in smoke in a matter of two weeks.

Russia is a mixed-bag as it has been cut off from Europe economically, culturally, and politically (in terms of influence), but it is now a much more disciplined state thanks to the backfiring sanctions regime leveled against it.

China? Remains to be seen.

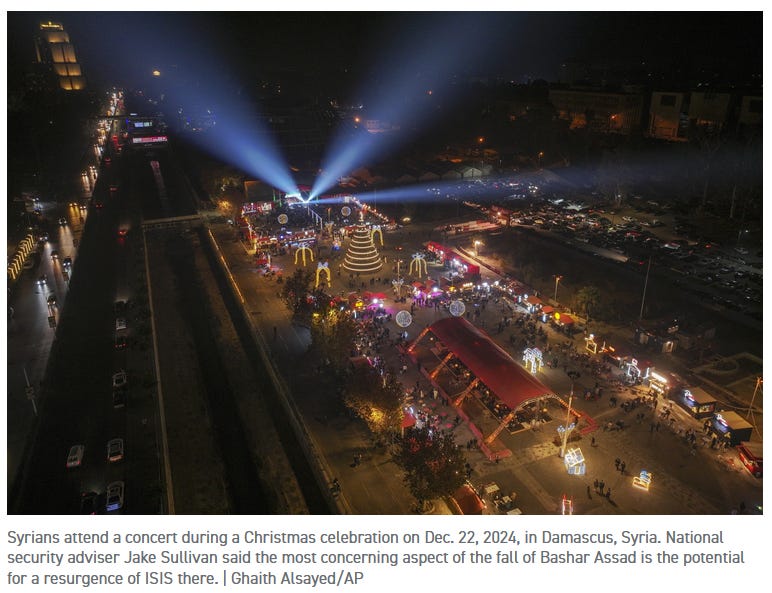

In discussing specific international situations, Sullivan told Zakaria that the most concerning aspect of the fall of Syrian strongman Bashar Assad is the potential for a resurgence of ISIS there. He also said that while Iran has seemingly been weakened in recent months due to defeats suffered by its allies in Syria and Lebanon, Iran might lash out in response.

When good things happen, Sullivan cautioned, “there are frequently bad things lurking around the corner.”

The Russia-Ukraine war is ongoing. Sullivan, who is to be replaced in his position by Rep. Michael Waltz (R-Fla.), urged Trump to maintain the pressure on Russia that President Joe Biden has applied to President Vladimir Putin’s regime since the start of the Ukraine war.

“We need leverage,” Sullivan said to get an equitable deal between Russia and Ukraine. “And that leverage is continued military support for Ukraine.”

Taking Syria off of the board is a blow for Russia (especially if they lose their naval re-fitting station), but at the same time the collapse of the Assad regime actually gives the USA less leverage with Russia regarding Ukraine now that Syria is done.

For 2025, eyes should be focused on:

what kind of regime/situation will take hold in post-Assad Syria?

is peace possible in Ukraine?

will this finally be the year that the USA pivots to East Asia?

Protests are still ongoing in Georgia, but it seems like the new government is not going to fall, as they have sworn in a new President, and the previous one is willing to leave the building (but will continue to insist that she is the only real “legitimate” President of Georgia).

I wrote about the anti-government demonstrations in Georgia a few weeks ago, wondering why they have been more subdued than the ones that resulted in the Rose Revolution in 2003:

Outgoing President Salome Zourabichvili has thrown in the towel, telling supporters that she will be leaving the Presidential Palace:

Georgia’s pro-western president, Salome Zourabichvili, has said she will leave the palace but remain the country’s legitimate officeholder, after refusing to hand over the keys to her successor in the wake of a controversial general election.

Zourabichvili spoke as thousands of protesters gathered in the capital, Tblisi, to demonstrate against the inauguration of Mikheil Kavelashvili, a former football player turned far-right politician backed by the ruling pro-Moscow and increasingly authoritarian Georgian Dream (GD) party, who was sworn in as president at a parliamentary ceremony.

The inauguration of Kavelashvili – which for the first time in Georgia’s history was held behind closed doors in the plenary chamber inside parliament – is likely to further escalate a months-long political crisis during which there have been large pro-European Union demonstrations.

At least 2,000 pro-EU protesters had gathered outside parliament before the disputed presidential inauguration.

Addressing the protesters moments before the inauguration, Zourabichvili, who has become a rallying figure for those opposed to GD, declared: “I remain the only legitimate president. I will leave the presidential palace and stand with you, carrying with me the legitimacy, the flag and your trust.”

Venezuela had Guadio, Belarus has that Svetlana woman, and now Georgia has Salome.

After taking the presidential oath in parliament, Kavelashvili said: “Our history clearly shows that, after countless struggles to defend our homeland and traditions, peace has always been one of the main goals and values for the Georgian people.”

The GD party has presented itself as the sole guarantor of stability in the country, accusing the west of trying to drag Tbilisi into the Ukraine conflict.

Kavelashvili, known for his far-right views and derogatory comments against LGBTQ+ people, went on to praise “our traditions, values, national identity, the sanctity of the family, and faith”.

The standoff between Zourabichvili and GD had plunged the country into a political crisis following the contested election in October that GD had won but many Georgians believe was rigged with Russia’s help.

Zourabichvili and protesters have declared Kavelashvili “illegitimate”, demanding a rerun of the October general elections.

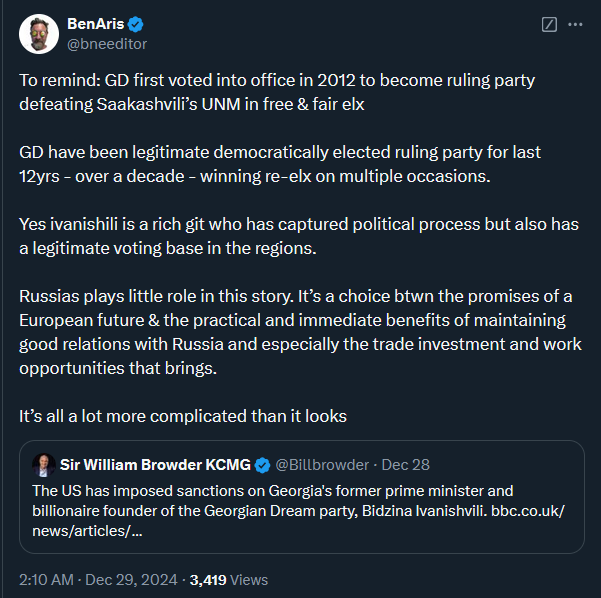

What Georgian Dream (GD) do not want is to turn their country into another Ukraine, something that the USA and some in the EU are all too happy to do to “stick it” to the Russians. Russophilia in Georgia is nowhere near a majority position for various historical reasons, but Georgians are a conservative people who do not want to take another risk like former leader Saakashvili did in 2008 when he tried to liberate North Ossetia using force against Russian peacekeepers. GD are being both prudent and pragmatic, with the opposition idealistic to the point to recklessness.

Naturally:

Weighing in on the crisis, US Republican congressman Joe Wilson has said that Zourabichvili is invited to attend Donald Trump’s inauguration next month “as the only legitimate leader in Georgia”.

He announced a bill “which will prohibit US recognition of the illegal dictatorial regime in Georgia and recognise Zourabichvili as the only legitimate leader in Georgia”.

But the prime minister, Irakli Kobakhidze, of the GD party, has ruled out calling fresh elections. He had had said that Zourabichvili would face legal consequences if she chose to stay in office.

The USA is already sanctioning key Georgian government officials.

Will the incoming Trump administration clean out the US State Department of the Nuland-regime changers?

I’ll give Ben Aris the last word:

“You want Foucault? I’ll give you some Foucault.” (The following shared essay doesn’t have much Foucault in it, to be honest).

I won’t say much now as I have a longer-term plan to do a series on the infamous French philosopher….but I will share this essay that argues that he is not to blame for the rise of “Identity Politics”, and says that “ontological absolutism” is where you really should direct your anger:

Sadly, the vision of academic pursuit in the social sciences and humanities being guided by disinterested inquiry is obsolete. Job descriptions, not just in the humanities but also in the empirical sciences, increasingly demand explicit ideological and activist orientations (e.g., decolonialism, environmental justice, anti-racism). Analytic distance and critical detachment are denounced as outmoded colonial vestiges of cisgendered white male supremacy. Meanwhile, a scholar’s identity and therefore their experience is privileged, especially if they are from underrepresented groups where a tacit and often condescending expectation often exists that their topics of research overlap with their identity. Academic pursuit guided by nondogmatic, open-ended inquiry hears its death knell.

A popular explanation for this larger shift blames the abandonment of the pursuit of truth as root cause and points the finger at social constructivists like my doctoral adviser. This argument is epitomized by public intellectual Yascha Mounk’s recent book The Identity Trap which names the usual suspects—the French philosopher Michel Foucault, critical theory, and the bogeyman known as “postmodernism”—as key culprits of the new dogmatism. With truth dead, everything is permitted.

Yet as someone who grew up intellectually in this milieu, I believe that today’s stridency and moral absolutism is less explained by social constructivism but by its rejection. While social constructivists emphasized doubt, ambivalence, and uncertainty, academics now speak with absolutist, if imaginary, moral clarity on a host of issues ranging from the COVID-19 pandemic to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

I can see his point…….

Ontologists not only make broad and foundational claims about the world but also normative claims about how it should be. If knowledge-oriented social constructivists were focused on how our ways of seeing the world were filtered through our own cultural and historical lenses, ontologists attempt to break through the filters to get to absolutes. In other words, while epistemology was narrow and limited in its focus on human understanding, the new ontologists aimed to move “beyond the human,” forming part of a wave of “animal studies” that spread throughout the humanities. A key text of the “ontological turn” in anthropology argues “how forests think” (the short but confounding answer: in 19th-century American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotic theory).

While tendencies toward these kinds of abstract mystifications would lead more politically radical academics to accuse the new ontologists of—what else?—not being politically radical enough, ontologists themselves made a key contribution to the new polarization, especially in how their work translated to wider popular readings, by embracing binary logics—most notably, between so-called Western and non-Western (usually indigenous) ontological realities. Invariably, these dichotomies take on a moralistic dynamic: Western ontologies are bad because they are colonialist, ableist, capitalist, racist, misogynist, and so on and so on, invariably leading to planetary destruction. Non-Western ontologies are not only good but necessary for our salvation, often from, in increasingly apocalyptical tones, the perils of climate change. It goes unmentioned that the archaeological record is dotted by the collapses of non-Western societies that somehow managed to destroy their own environments.

The author gives us lots to think about, but I will skip ahead to the concluding paragraph:

In 1994, Michael Ignatieff asked Eric Hobsbawm if he would have rejected communism if he had known of Stalin’s atrocities during the 1930s. Hobsbawm infamously answered, “probably not” because such “sacrifices” could be justified and “the chance of a new world being born in great suffering would still have been worth backing.” Our new academic radicals appear willing to embrace Hamas’ atrocities to create a new world in the service of a speculative fantasy that imagines that the region might erupt in peace and harmony if Israel magically or not-so-magically ceases to exist. If the world is the horror they consider it to be, one readily understands what horrors they will countenance in order to transform it. And while it is tempting to dismiss the thinkers of these obscure theories as deeply unserious and not worth taking seriously, it is a mistake to underestimate their influence throughout academe.

And before someone says it: yes, this essay is self-serving from an ethnic standpoint. That should make it an even MORE interesting read.

We end this year’s last SCR with a review of a new biography of Stanley Kubrick. I guess I am not too creative and far too conservative, as I cannot decide between Kubrick and Fellini as to who is the greatest film director of all-time:

Kubrick’s photographs for Look are hard-edged and commanding; they fix an image once and for all. Far from being illustrations, they have a quality – a little like Weegee’s – at once random and composed. In one, the circus director John Ringling North dominates the right half of the frame, shouting instructions to an unseen person, while above and to the left a high-wire act has two showgirls suspended from the wheels of a bicycle: the picture frame is divided by a balancing bar carried by the cyclist. In another, a scientist works with a slab of white-hot metal, shielded from the dazzling light by opaque goggles. Kubrick also photographed celebrities like Montgomery Clift and Rocky Graziano. His aesthetic was realist, no gimmicks allowed, but he never stinted on drama: a news vendor, looking contemplative beside a headline that reads ‘FDR Dead’, was told to look sadder. The vendor complied, and the result was a picture ready to receive the caption ‘A Nation in Mourning’. Kubrick told Jack Nicholson many years later that a photograph is a copy of life, but ‘in movies you don’t try and photograph the reality, you try to photograph the photograph.’ Did this mean that the film is the more real of the two copies by virtue of its conscious abstraction? Reality, he seems to have felt, is an unlisted bottom floor – hard to get to and, once you have got there, hard to the touch.

There was a movie theatre on almost every block in his part of the Bronx, and, as he told Jeremy Bernstein in a 1966 interview, ‘I used to go to see films ... practically every film.’ Art-house theatres scarcely existed yet, but you could buy a ticket to the Museum of Modern Art, where they showed Chaplin, Griffith, Von Stroheim, Eisenstein, Murnau, Pabst, Lang. For the greats of the silent era, Kubrick seems to have felt a veneration free of envy. The typical American product of the 1940s drew a different response: he was sure he could make something better. For Kubrick (according to Michael Herr, his friend and collaborator on the screenplay of Full Metal Jacket), ‘there was definitely such a thing as a bad movie, but there was no movie not worth seeing.’ He told Herr in an exuberant moment that The Godfather must be the greatest movie ever made. When challenged he backed off a little: it was the movie with the greatest cast. This points to a curious fact about Kubrick’s own work with actors. There are magnificent performances in his movies – by George C. Scott, James Mason, Peter Sellers, George Macready, Kirk Douglas, Nicole Kidman, Sterling Hayden; and in smaller roles, Slim Pickens, Peter Ustinov, Sue Lyon, Leonard Rossiter, Shelley Winters, Sydney Pollack – but there is never a trace of ensemble feeling. The actors, and for that matter the characters, are monads, each in a separate cell.

Click here to read the review in its entirety.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

And please don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already!

Europe has gone through a Centurus Horribilis. Hope 2025 is the dawning of a new age. At least the GAE color revolution playbook failed in Georgia. Jake Sullivan can retire as a stay at home husband to his fellow swamp creature wife Maggie, who just carpetbagged a Congess seat. The downfall of the regime came on November 5: https://yuribezmenov.substack.com/p/downfall-kamala-2024-election