Saturday Commentary and Review #176

Pity Lebanon and Pity the Lebanese, The History of Germany's BfV, Ceding Patriotism to the Right, Infighting in Anti-Putin Exile Community, "Doom Scrolling"

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

Robert Fisk was a British journalist and a very, very polarizing figure when it came to the Middle East. A bleeding heart liberal, he was never shy in playing favourites (he had a thing for underdogs). This made him many enemies over the years, but his reporting was not to be missed.

I first heard of him thanks to his reporting on the Middle East in his column in the UK Independent. He then tackled the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina, with a predictable focus on the trials and tribulations of the internationally-appointed “victim”, the Bosnian Muslims (now known as “Bosniaks”). Naturally, I had issues with his reporting on that conflict.

In 2002, his book “Pity the Nation - Lebanon at War” (now re-titled “Pity the Nation - The Abduction of Lebanon) was released. A massive book spanning Lebanon from the beginning of its civil war up until the pullout of the Israeli forces from that south of that country, it was quite ambitious in its goals, and is a must-read, no matter your personal views regarding Fisk’s reporting. This book has had a lasting impact on me personally, because it dives quite deeply into subject matter that doesn’t earn such treatment in most western media.

“Pity the Nation”…..pity the nation. I cannot help but feel pity for Lebanon. It is a land held hostage by geography and history, sitting along a civilizational fault line in a region that is routinely rocked by man-made earthquakes in the form of conflict. A Neo-Ottoman polity complete with a political millet system of governance, the creation of the State of Israel (and the reaction that its creation caused) effectively doomed Lebanon, leading to its present failed state status. Lebanon is a failed state: a patchwork of rival confessional groupings, all with their own much larger and more powerful patrons, albeit in varying scopes of patronage.

The repeated failures of the Arab states to extinguish Israel led to the occupation of the West Bank (and Gaza). The arrival of the PLO on Lebanese soil destabilized that country to the point that it led to a civil war that ravaged it so thoroughly that it has never been able to recover since. The Syrians occupied it, playing favourites. The Israelis occupied much of it, giving birth to Hezbollah, its mortal enemy (and do not forget that Israel assisted in the rise of Hamas to split the Palestinians into two factions). It’s a mess.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar have their favourites in Lebanon, their fellow Sunni Muslims. Iran and Syria slot alongside Hezbollah. Its Christians are split between supporting moderate Sunnis and the Shi’a, with some happy to see Israel hit Hezbollah, but with most lamenting the loss of a Lebanon-that-once-was, with Beirut “the Paris of the Levant”, and the western backing that it once had……western backing that now works for Israel rather than for the Christians who held firm under centuries of Islamic rule.

What these past few decades have taught us is that much of the post-Ottoman world has not managed to progress to the next stage of societal development, that of the nation-state. Ba’athism failed in both Iraq and Syria, and a Lebanese nationalism that spans confessional differences has never managed to take hold either. Albania has managed to function despite having similar confessional differences, but in my view Albania has had the luxury of being ignored and left to its own devices for a century now, unlike Lebanon.

Geography can be cruel. I am reminded of when Stalin informed the Politburo that the USSR would attack Finland. Taken aback, Molotov and the others expressed shock at the decision. Stalin is reported to have replied: “I am not responsible for geography!”. “Uncle Joe” had a penchant for gallows’ humour.

I am sharing this essay on Lebanon not to suggest that it is the “correct” take on the situation there as it was just prior to/at the start of Israel beginning its bombing campaign and its invasion (it was published on the 27th of September), but rather as a point of reference. The author clearly feels that regime change (he says “contain”, but I am calling bullshit) in Iran is the only way to “stabilize” the Middle East, as is made plainly evident in the following quote from the essay:

“The pretence that the Palestinian and Lebanese questions could be contained, ignored or bypassed as part of a wider grand strategy to contain Iran has been shattered.”

The quote does seem correct in that a wider deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia (plus other Arab states) is impossible without figuring out what to do about the Palestinians in Gaza and on the West Bank. The proposed resolution requiring a “containment” (read: regime change) risks opening up the proverbial Pandora’s Box of unforeseen outcomes, while absolving Israel of any and all responsibilities to address its occupation regimes….but we are getting a bit ahead of ourselves here.

The root of the hopefulness could be found in the Abraham Accords, that potentially transformative set of Trump initiatives, the aim of which was — somewhat euphemistically — to “normalise” relations between Israel and some of its Arab enemies. Last September, the great glittering prize of Middle East peace seemed to be in touching distance: Saudi rapprochement with Israel.

The radical idea at the heart of Trump’s plan was that regional peace did not need to wait for “the Palestinian question” to be solved. Instead, that could be put to one side while other grand strategic moves played out. As Mohammed bin Salman “modernised” Saudi with his combination of political repression and social liberalisation, the two great anti-Iranian powers in the region could finally be brought together. A similar assessment was made about Lebanon, a country without a functioning state or economy and at the mercy of Iran’s colonial army, Hezbollah. This, also, was a situation that was thought to be containable — even as Iran exploited the anarchic chaos of Iraq and Syria to supply its proxy with enough weapons to devastate Israel.

The central conceit of the Abraham Accords was that, irrespective of Hamas, Hezbollah and the occupation of the West Bank, once the Israel-Saudi axis was formed, Iran could be pushed back and contained without direct American involvement. But, then, the depth of Hamas’s murderous brutality on 7 October shattered that assumption, leaving not only a traumatised and vulnerable Israel, but also a traumatised and vulnerable Western order forced to confront the stark realities of the Middle East.

The fulfillment of the Abraham Accords would be Israel’s greatest diplomatic and strategic triumph, as it would mean the abandonment of the Palestinians by their fellow Arabs, plus the tightening of the noose around Iran, as the Middle East’s Jews and Sunni Arabs would be able to form a common front against the Shi’ite regime in Iran. Occam’s Razor suggests that Hamas’ (a Sunni outfit, just to confuse matters even more) raids into Israel one year ago must have gotten approval in Tehran in order to attempt to scuttle the implementation of the Abraham Accords. Funnily enough, this has not received much media treatment in the West. What makes it even odder is just how anti-Iran this media is. We are going to have to wait to see if Occam was right in this instance.

Today, Lebanon is a dead state, eaten alive by Hezbollah’s parasitic power. The scale of the catastrophe in the country is hard to comprehend, much of it caused by the disruptive nature of Syria’s civil war. Since its neighbour’s descent into anarchic hell, some 1.5 million Syrians have sought refuge in Lebanon — a tiny country with a population of just 5 million. But, more fundamentally, with Hezbollah fighting to protect Bashar al Assad, the opposing countries — led by Saudi Arabia — began withdrawing funds from Lebanese banks. This sparked a financial crisis that left Lebanon with no money for fuel.

Hezbollah filled in the void created by the collapse of Lebanon by its civil war, and in reaction to the Israeli occupation of the south of that country, where many of its Shi’ites reside. The author also fails to note that the civil war in Syria was an effort launched by the West in alliance with various Sunni Arab regimes, and that the Israelis were all to happy to stoke by aiding al-Nusra (al-Qaida) in Syria’s southern province of Da’raa, which lies next to the occupied Golan Heights (now recognized by the USA as officially part of the State of Israel). The Sunnis did tank what was left of the economy in Lebanon, but one cannot begrudge Hezbollah’s state-within-a-state approach, as Lebanon was already a failed state prior to that. You gotta look out for your own.

A concession:

By spring 2020, the country had defaulted on its debts, sending it into a downward spiral which the World Bank in 2021 described as among “the top 10, possibly top three, most severe crises globally since the mid-nineteenth century”. Lebanon’s GDP plummeted by around a third, with poverty doubling from 42% to 82% in two years. At the same time, the country’s capital, Beirut, was hit by an extraordinary explosion at its port, leaving more than 300,000 homeless. By 2023 the IMF described the situation as “very dangerous” and the US was warning that the collapse of the Lebanese state was “a real possibility”.

With Iranian support, however, Hezbollah created a shadow economy almost entirely separate from this wider collapse. It could escape the energy shortages, while creating its own banks, supermarkets and electricity network. Hezbollah isn’t just a terrorist group. It is a state within a state, complete with a far more advanced army. “They may have plunged Lebanon into complete chaos, but they themselves are not chaotic at all,” as Carmit Valensi, from the Institute for National Security Studies at Tel Aviv University, told the Jerusalem Post.

What were the Shi’a supposed to do? What they have done in Southern Lebanon has been remarkable, but I will say this: supporting Hamas since October 7, 2023 looks like it might have been a mistake.

Then came 7 October, after which Hezbollah tied its fate to that of the Palestinians, promising to bombard Israel with rockets until the war in Gaza was brought to a close. We have witnessed the frightening scale of its power over the past year, its bombardment forcing some 100,000 Israelis from their homes in Galilee to the safety of the Israeli heartlands around Tel Aviv. For the first time since modern Israel’s creation, the land where Jews are able to live in their own state has shrunk; the rockets are a daily reminder of the country’s extraordinary vulnerability, threatened on all sides by states who actively want it removed from the map — even from history itself.

Hezbollah, deciding to act as the champion of the Palestinians of Gaza, makes perfect sense in the zoomed out historical sense, but what it has done by entering this conflict on the side of Hamas is to internationalize it, acting from a geographic location contained within a failed state, effectively holding Lebanon hostage to its decision. Naturally, the Israelis were never going to tolerate the security situation in Galilee, and naturally, the Israelis see an opportunity to settle scores with a force that embarrassed them back in 2006. The power vacuum in Washington DC courtesy of the election and presence of the an Alzheimer’s case in the White House has provided Israel a short window of opportunity to press its advantage.

First this:

With Gaza lying in ruins and Hamas devastated but not defeated, Israel has concluded that it is now strong enough to wage war on Hezbollah, and that any delay only serves the interests of its enemies, principally Iran.

The stakes today are far higher for Israel than the war it has been waging in Gaza for the past 12 months. This war against Hezbollah is one that must reestablish the ability of Israel to be able to shelter its citizens within its own borders. It is, then, a battle for the very purpose Israel was founded.

And then this:

In its ignorance and arrogance, the West believed it could contain the appalling disorder of the Middle East. But it has simply allowed Iran to grow in strength. Not only did 7 October shatter the failing assumptions of Benjamin Netenyahu’s grand strategy, it also revealed the Western world’s myopic passivity too. Today, the world is reaping the whirlwind.

Gaza has been reduced to rubble, but Hamas is not defeated

Israel has not been defeated

Hezbollah’s Senior Command has been killed off, but as of yet, it is not defeated

The question of how the Palestinians and the Israelis are supposed to live next to one another has not been resolved in any side’s favour, nor through any agreements requiring concessions

The author feels that the West could have “fixed” all of this by confronting Iran instead. This reeks of the neo-conservatism of the Bush Era, and I think that this is the direction that we are headed towards no matter who occupies the White House next year.

Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz.

The above words translate into: The Federal Office For the Protection of the Constitution. Germans love super-long compound words, so get ready to learn a few more as we dive into the history of the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV), beginning with the Allied Occupation of Germany up to the present day.

The BfV is back in the news lately because of the threats to ban the AfD (Alternative for Germany) from participating the German electoral process. BfV plays the key role in this process, as it is the government arm tasked with collecting information on anti-constitutional elements within German politics and society, but without the powers of arrest. You have seen me bring this up a few times over the past three years here, but we finally (!) have an excellent treatment of not just this specific threat, but of the history of this arm of German government, courtesy of German economist and sociologist, Wolfgang Streeck, a favourite of this Substack.

A lot of this is new to me, which is why I don’t have much to add to it. It’s a long read, clocking in at over 4,000 words. Let’s dive in:

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, or BfV) owes its existence to the Allies. When the Western powers gave the green light for the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany in their zones of occupation in 1949, they also gave the constituent assembly permission to set up ‘an office to collect and disseminate information on subversive activities against the federal government’. According to Ronen Steinke, the intention was to nip in the bud any attempt at a coup d’état, whether fascist or communist, that would have given the Soviet Union an excuse to invade western Germany. (Instead, the Soviets founded their own German state, the German Democratic Republic.) In post-fascist Germany, where memories of the Gestapo were still vivid, setting up a domestic intelligence agency for political surveillance was a politically sensitive move. The Allies had already passed a statute in 1946 disbanding ‘any German police bureaux and agencies charged with the surveillance and control of political activities’. Three years later, writing to the constituent assembly, they reiterated that the new agency ‘must not have police powers’.

So far, so good. Now check this out:

This injunction is still observed. BfV agents aren’t allowed to arrest people; they don’t wear uniforms or carry guns. ‘They’re meant to listen as inconspicuously as possible,’ Steinke writes, ‘and take notes.’ Their job, as stated in the legislation, is ‘the collection and evaluation of information ... on activities against the free democratic basic order’. Defending the state against threats to this order is the domain of the police and public prosecutors, sometimes acting on information provided by the BfV. The BfV is subordinate to the Ministry of the Interior, and is therefore subject to political instruction, in a way that, say, the office of the public prosecutor is not. Today, nudged by its masters, it has extended its responsibilities from the observation of subversive activities to their prevention.

Streeck highlights how its agents have now moved from observation to prevention. This is an important shift in their tasks.

Interesting history:

The BfV was founded in 1950 with a staff of 83. Little is known about its early activities, other than that the majority of its staff were former Nazis, as was the case in most branches of the federal bureaucracy. Its first president, Otto John, had been active in the resistance, escaping to London after the failed putsch of 1944. In 1954 he popped up in East Berlin and revealed in a press conference that the soon-to-be West German Ministry of Defence and the foreign intelligence service that was about to become the BND both employed former SS leaders. After two years in the GDR he returned to West Germany, claiming that he hadn’t gone east voluntarily, or switched sides, but had been abducted. He was sentenced to four years in prison for treason and conspiracy.

Within a few years, the BfV had helped the federal government ban two political parties that had been deemed anti-constitutional, the Socialist Reich Party (SRP) in 1952 and the Communist Party (KPD) in 1956. The categorisation of political parties as anti-constitutional and their subsequent outlawing is peculiar to the German system. Cases are brought by the government and adjudicated by the constitutional court using evidence collected, typically, by Verfassungsschutz officers. The Allies shared the state’s interest in seeing the SRP and the KPD disbanded – the SRP was by its own admission a successor to the Nazi Party and the KPD was essentially the West German branch of the GDR’s ruling party, the Socialist Unity Party (SED). German governments have always viewed party bans as primarily a political, rather than a legal, matter. This was made clear in 1968 when the then minister of justice, Gustav Heinemann, a Social Democrat, invited two representatives of the KPD to his office to inform them that if a new communist party were founded nothing would be done to suppress it. Shortly afterwards that party came into being – as the DKP – and lasted until German unification, when it merged with the SED to form the party now known simply as Die Linke (‘The Left’).

The banning of both the SRP and KPD makes perfect sense, even in hindsight.

Expansion of the BfV:

Under Willy Brandt, who became chancellor in 1969, and his successor, Helmut Schmidt, the BfV thrived. Its staff more than doubled from around one thousand in 1969 to more than two thousand in 1980. It expanded again during the war on terror, and then in the wake of Angela Merkel’s opening of the German border in 2015. By 2022 it had a staff of more than four thousand and a budget of €440 million. In the meantime all sixteen federal states, the Länder, had established Verfassungsschutz offices of their own, employing an estimated 2600 officials. Add to this the unknown number of so-called V-Leute – paid informers who spy and report on suspected anti-constitutional activities; Steinke estimates that there are around 1500 of them – and you get roughly 8400 fighters for the constitution fielded by the seventeen governments of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Close to 10,000 people working as political secret police. the number of V-Leute (informants) is nowhere near the scale of the former East Germany (DDR), where the secret police had 90,000 employees, assisted by almost 200,000 paid informants.

A political shift:

Steinke gives a fascinating account of the way the BfV’s activities and concerns have changed over time. Unsurprisingly, the former Nazis tasked with protecting the democratic constitution in its early years were keen to go after the left, and this remained the BfV’s priority well into the years of student revolt. In 1972, the Brandt government and the Länder passed a decree banning the employment of ‘enemies of the constitution’ (Verfassungsfeinde) in the public sector, aimed primarily at a new generation of teachers and academics who were seen as potentially lacking loyalty to the state. Under the decree, which was rescinded at the federal level in 1985 and by the final Land, Bavaria, in 1991, 3.5 million people, both applicants for and holders of public sector jobs, were subjected to loyalty checks, carried out by the relevant Verfassungsschutz office. In total, 1250 applicants were refused employment and 260 employees dismissed, almost all of them deemed too far to the left to be capable of serving the public interest.

After the collapse of the GDR, and with the post-communist transformation of leftism into what Jürgen Habermas has called ‘constitutional patriotism’, the BfV’s attention began to shift to the right. After unification, right-wing ‘populist’ political parties came to be seen as electoral competition by Germany’s centre-right and centre-left: the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the Christian Social Union (CSU) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). In 2001, Gerhard Schröder’s government and both chambers of parliament filed a joint motion to the constitutional court to outlaw the far-right National Democratic Party (NPD), which seemed close to crossing the threshold – 5 per cent of the vote – that would give it representation in parliament. As in the 1950s, it fell to the BfV to assemble the evidence. The case was thrown out by the constitutional court in 2003, on the basis that it was impossible to know how much of this evidence – mostly speeches and party resolutions – had been produced by undercover V-Leute who had joined the party. The problem was exacerbated by the refusal of the BfV to identify its agents, for fear of retribution by genuine party activists. It transpired that the federal and Länder bureaux had kept their agents secret from one another. They continued to do so during the trial, raising the possibility that a majority of those serving on the NPD’s internal committees may have been V-Leute who didn’t know who was and who wasn’t on their side. The BfV was ridiculed for allowing its spies to become indistinguishable from the party they were spying on.

The NPD was so riddled by state agents that the attempt to ban them failed.

In September 2015, when the NPD case was pending, Merkel opened the German border to more than a million refugees, profoundly changing the country’s politics for years to come. In the wake of her decision, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), founded in 2013 in neoliberal opposition to European monetary union, emerged as a right-wing populist competitor to Merkel’s CDU and its Bavarian sister party, the CSU. The question of how the AfD and the ‘refugee crisis’ should be handled was fiercely contested within Merkel’s political alliance in the run-up to the 2017 federal election, and in its aftermath. While Merkel may have hoped that opening the border would enable her to switch from a coalition with the SPD to one with the Greens, the CSU, led by Horst Seehofer, shared the AfD’s antipathy to her border policy and for a while seems to have considered the AfD as a coalition partner. This sharpened the BfV’s dilemma over whether its focus should be on left-wing radicalism, as preferred by Seehofer, or on the right, now in the form of the AfD, as Merkel wanted.

Seehofer and the CSU did agree an alliance with Merkel for the 2017 election, but also extracted a promise from her that she wouldn’t run again. This meant that the BfV’s focus had to move to the AfD, which was rapidly becoming an effective electoral force. The then BfV president, Hans-Georg Maaßen, a lifelong CDU member, was deeply uncomfortable with this. Although Seehofer kept him on when he became minister of the interior in the grand coalition government put together by Merkel in 2018, Maaßen increasingly came to be seen as a political liability – he publicly disagreed with Merkel’s claim that a video of an anti-immigration rally in East Germany showed a ‘manhunt’ of refugees, for example. Not long afterwards, Maaßen made public the notes for a speech he had given at a secret international meeting of domestic intelligence services. In them he claimed that the SPD, Merkel’s coalition partner, had ‘radical leftists’ in its ranks. The SPD demanded Maaßen’s dismissal, and in November 2018 he was sacked.

Maasen was not only sacked, but was later put under the “observation” of the BfV by his successor who is also his former party colleague!

Concrete forms of “anti-constitutional extremism”:

His successor, Thomas Haldenwang, was also a CDU member, though of a more Merkelian sort. According to Steinke, in January 2021 he was about to publish a report announcing that his office had found the AfD suspect of anti-constitutional ‘extremism’ and was placing it under formal observation (which would allow intelligence methods such as wiretapping and infiltration by undercover agents), when he was called to Seehofer’s office. The draft report, which Seehofer had been sent, had cited a prominent AfD politician saying ‘Islam does not belong to Germany.’ Seehofer’s problem was that he and other leading CSU members had repeatedly used those same words. (In 2010 the then federal president, Christian Wulff, a Merkel protégé, had stated that not only Christianity and Judaism ‘belonged to Germany’, but that Islam did too. ‘Der Islam gehört zu Deutschland’ immediately became a slogan of the Merkel wing of the CDU.) The report also noted that ‘agitation against refugees and migrants is the central theme of the public statements of AfD units, where xenophobic patterns of argument combine with Islamophobic resentments,’ and held this to be anti-constitutional. On Seehofer’s insistence this and other passages were toned down or deleted. The final version, approved by the minister more than a month later, stated that ‘advocacy of a restrictive immigration policy is in itself constitutionally irrelevant.’ Only then, in February 2021, did Seehofer give the BfV permission to start its formal observation of the AfD.

I’ll leave it to Streeck to provide us some closing words:

Today, the BfV and the sixteen Landesämter form a central pillar of an institutional regime that bridges state and civil society, and aims at the manufacture of political consent and what has recently come to be called ‘social cohesion’. Underlying this is the peculiar readiness of German elites to carry out orders even before they are given, which means that they may not have to be given at all. Visitors from countries with a tradition of accepting or even respecting eccentricity, such as the UK, France and Italy, or from a country as fundamentally disorderly as the United States, tend to be struck by the monolithic appearance of German politics and society, the way everything seems to fall in line with everything else. This is enabled by the interplay between institutions, formal and informal, and by a culture that perceives dissent as selfish and as a threat to social and political unity (it’s also seen as pointless).

Wolfgang is criticizing Germans for being German.

In the current “West”, nationalism is largely equated to fascism by governing elites. This is a relatively new development, as such ridiculous claims were once the preserve of Marxist-Leninists who dismissed any national sentiment as “bourgeois”, and therefore to be extinguished in the class war. Our countries are supposed to be open and tolerant, cosmopolitan and global. All other forms of societal organization are fascist (and racist).

The concession of national sentiment (belonging to a political community based around the concept of “the nation”) to the right means that all such feelings of belonging are now de facto “right wing”. This would not be a problem for the centre-right, centre, centre-left, and left if nationalism was disappearing, as many had predicted that it would. Instead, nationalism continues to persist and to expand, much to the consternation of anti-national elements.

There are those on the political left who now realize the danger of ceding nationalism (or patriotism) to the right. These left wingers are much more intelligent than those spanning the centre-right to the centre-left, as they realize that the nation isn’t going anywhere, and to succeed at reforming their own countries requires winning over such elements to their cause.

Jacopo Custodi has set off a firestorm in left-wing circles when his essay on this subject was recently published in Jacobin:

At various points in history, many authors have argued that nationalist politics was entering its final phase. In early nineteenth-century liberal thought, there was already the belief that nationalism was a declining phenomenon, destined to disappear soon with the expansion of global trade. The idea that people’s national identity (their nationality) was losing importance due to the expansion of world capitalism was shared by Marx in his youth (though not in his more mature writings). This position enjoyed a certain popularity in both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, albeit cyclically: it disappeared during periods when nationalisms erupted or clashed militarily, only to resurface in subsequent periods.

In the 1980s, Eric Hobsbawm suggested that the great increase in studies on nationalism was a sign that the phenomenon had finally entered its concluding historical phase: “The owl of Minerva which brings wisdom, said Hegel, flies out at dusk. It is a good sign that it is now circling around nations and nationalism.” Hobsbawm was correct in noting that studies on this subject had significantly increased during those years; however, his hope, like that of others before him, proved erroneous. Only a few years later, with the fall of the Socialist Bloc and its fragmentation into numerous nation-states, there was an outburst of several nationalist claims and conflicts that were thought to be outdated.

It wasn’t just Hobsbawm who got it wrong:

In the relative optimism of the 2000s, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri reiterated the view in Empire that global capitalism was at last wiping out the reactionary narrowness of national belonging. Thus national identity came to be seen not only as something to be rejected politically but also as an issue of minor significance. And yet, in the last decade, we have once again witnessed the resurgence of the nation as a conflicting political identity, largely championed by right-wing or separatist movements. Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, the rise of Scottish independence in the United Kingdom and Catalan independence in Spain, the electoral success of several nationalist right-wing parties across Europe, and the dramatic Russian invasion of Ukraine with increasingly radicalized Russian and Ukrainian nationalisms — all these diverse phenomena share a common denominator: the mobilizing power of national identity.

National identity continues to be the strongest force when it comes to mobilizing collective action…..at least in the West.

This is an excellent, excellent paragraph:

It is undeniable that the political power of nation-states is diminishing in many parts of the world, weakened by an increasingly globalized economy and the growing strength of transnational corporations and organizations. However, this should not be confused with the political decline of national identities, a conflation Hardt and Negri made in their book. On the contrary, the weakening of nation-states’ power often goes hand in hand with the spread of nationalist sentiments. Globalization, migratory flows, the neoliberal dismantling of the welfare state, and the decline of deeply rooted collective identities such as religion and class belonging seem to have strengthened national identity. This is reminiscent of Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman’s characterization of contemporary society as “liquid,” marked by instability, precariousness, and uncertainty: a society based on fluidity and mobility, where social relations and structures are unstable and changeable, leading to increasing inequality and a loss of community and solidarity. In the face of this reality, national identity has reemerged as a safe haven for people seeking a sense of belonging and community. It has become a symbolic identity to cling to in order to reduce feelings of alienation and uncertainty.

The feeling of national belonging has not withered away, but is getting stronger in many places as new economies and new technologies strip away other bonds. Patrick J. Buchanan has been right all along.

National belonging is still king:

According to the World Values Survey of 2017–2022, 88.5 percent of people interviewed worldwide stated they were “very proud” or “quite proud” of their nationality. Furthermore, the survey included only the nationality corresponding to the nation-state of the interviewee, thereby excluding minority nationalities, a factor that would likely have further increased the overall value. In Europe, as shown by the European Quality of Government Index, the nation remains the territorial identity to which citizens feel most attached, more than regional identities and much more than European identity. Finally, the popular classes, particularly those with lower levels of education, tend to be more “nationalized” in their culturalization process. This means they are more responsive to symbolic and cultural elements related to national belonging compared to individuals with higher educational or class backgrounds, who tend to be more culturally cosmopolitan.

A leftist argument for national sentiment:

In light of this situation, the Left cannot simply ignore the existence of national identities. These identities are integral elements of the political and social landscape in which the Left operates and, for the foreseeable future, they do not appear to be diminishing in importance. Thus, calls for the Left to reject national identity are a dead end and risk distancing it from its own popular traditions. On the contrary, it seems necessary for the Left to embrace — at least to some extent and in certain ways — national belonging.

This is not a novel idea: strange as it may seem today, the concepts of “left” and “nation” were originally not far apart. Hobsbawm goes so far as to suggest that these two political concepts not only arose from the same cradle — the French Revolution — but were also in some way synonymous. In the troubled French summer of 1789, the Third Estate declared itself the complete nation, initiating the French Revolution and boosting the very concept of nation at the political level. The estates-based political representation of the realm was about to be supplanted by the idea of the people-nation: the conflation of the nation with a collective entity, the people, as the bearer of sovereignty and in opposition to the privileged classes. When the people of Paris stormed the Bastille on July 14 and took control of the city, they did so in defense of the Third Estate, which had transformed into the National Assembly. Once the National Assembly was fully established, the supporters of the Revolution and the former Third Estate sat on the left side of the chamber. As such, they were described as both “the National Party” and “the Left,” creating the political concept of the Left at the same time.

Famed Marxist intellectual Antonio Gramsci:

Antonio Gramsci developed the concept of nazionale-popolare to indicate what is both national and popular. Initially, he specifically related it to cultural productions: literary or artistic works that express the distinctive characteristics of national culture and are recognized as representative by the popular classes. Today we use the term “national-popular” in a more general sense to refer to all those cultural, aesthetic, behavioral, and habitual traits widespread among the common people of a particular country. However, the concept in Gramsci’s writings also goes beyond its cultural dimension and concerns the identification of the popular masses with a common national project. For Gramsci, revolutionary struggle should not fall into “the most superficial cosmopolitanism and anti-patriotism.” Instead, it should forge a sentimental bond with the “people-nation.” Gramsci believed that every revolutionary movement striving to govern must embody and identify with the country itself, and this principle should also be applied to the working class in its hegemonic struggle against the bourgeoisie. This reflection did not arise in a vacuum; it was already sketched in the Communist Manifesto of 1848, when Marx and Engels wrote that the proletariat, to achieve victory, “must constitute itself the nation” and is therefore “itself national, though not in the bourgeois sense of the word.” One can hear in these lines the echo of the French Revolution, with the Third Estate turning itself into the nation. But there are different senses of being national.

Gramsci argued against cosmopolitan snobbery in favour of the national pride of the masses.

On the relative success of the post-war Italian Communists:

This is precisely the aspect that Jean-Paul Sartre identified as the key to the success of the postwar Italian Communist Party (PCI), which went on to become the strongest communist party in all of Western Europe. As longtime Italian communist Luciana Castellina recounts, Sartre said during one of his visits to Italy, “Now I understand [why the PCI is so strong], the PCI is Italy!” By this, Sartre meant that the party was not a separate vanguard but a body shaped by the same emotions, behaviors, and memories as the Italian people at large.

Click here to read the essay in its entirety, especially when he turns to the thorny issue of migration.

This SCR is probably the longest one ever, and we’re not even at the final segment yet. I’ll keep this part brief: the Russian opposition-in-exile is in disarray, with accusations of physical violence by one faction against another hitting the news. Normally, this would usually be framed as “Putin’s thugs target Russian dissident in violent attack”, but western media isn’t even bothering with that line this time:

When Leonid Volkov, a longtime associate of the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, was brutally attacked with a hammer outside his home in Lithuania in March, it initially seemed yet another case of the Kremlin hunting down its enemies abroad.

The assailant smashed open Volkov’s car window and struck him repeatedly with a hammer, breaking his left arm and damaging his left leg. Western officials and opposition figures assumed the attack, which took place a few weeks after Navalny’s mysterious death in prison, had been orchestrated by the Kremlin.

Then, last month, Navalny’s team released an explosive investigation that cast doubt on that version of events.

Is this some sort of factional jockeying?

In the video, Maria Pevchikh, the head of Navalny’s investigation department, accused the wealthy businessman and outspoken Kremlin critic Leonid Nevzlin of hiring the men to beat up Volkov outside his home, claiming the attack was triggered by a personal dispute.

Nevzlin has denied any involvement in the attack. In a statement on X, he wrote: “I have nothing to do with any attacks on people, in any form whatsoever,” adding that “justice will confirm the absurdity and complete baselessness of the accusations against me”.

In their investigation, Navalny’s team published screenshots they said showed conversations on the messaging app Signal between Nevzlin and an alleged associate, Anatoly Blinov, apparently discussing the attack on Volkov. Navalny’s team handed their dossier of evidence to Polish authorities, where Blinov was arrested in September.

The allegations have caused shock and led to infighting among members of the exiled Russian opposition, as people come to terms with the implications of the revelations, if true.

Pevchikh, of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, told the Guardian: “There isn’t a rulebook on what you do when you find out that someone you know stabs you in the back.

“Volkov was attacked three weeks after Alexei was killed. We had barely buried him. In the lowest point of our lives, someone pushes you from behind so you fall even more and suffer even more.”

Who is Nevzlin?

Nevzlin, a former executive and partner of the ex-oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky, gave up his Russian citizenship after the start of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and is now based in Israel, where he owns a stake in the Haaretz newspaper.

From Israel, Nevzlin has funded several media projects that are critical of the Kremlin and voiced staunch support for Ukraine in its war with Russia. He has previously clashed with other opposition groups, including Navalny’s team, over disagreements regarding the best approach to challenge Vladimir Putin, the Russian president.

Nevzlin is known for his more radical political views, including calling for the dissolution of Russia as a country and referring to the majority of Russia’s population as “slave cattle”.

Nevzlin is one of the many, many robber barons who plundered Russia during the privatization of the 1990s.

The Guardian was unable to verify the authenticity of the conversations, which also featured covertly shot photos of Volkov and other members of Navalny’s team living in Vilnius. “Time to do away with this moron,” reads one of the messages, which the Navalny team claims Nevzlin wrote.

They further allege that Nevzlin, in the messages, discusses plans to abduct Volkov in a way that would leave him “in a wheelchair” before handing him over to the FSB.

…and the biggest scumbag of them all, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, is now enmeshed in this affair as well:

The community of Russian dissidents living abroad has long been disposed to infighting, but the accusations against Nevzlin have provoked the biggest split in the opposition movement since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Navalny’s team has also accused Khodorkovsky, once Russia’s richest man who spent 10 years in prison after falling out with Putin, of being aware of Nevzlin’s alleged crimes before they became public.

Khodorkovsky has defended his former business partner Nevzlin, claiming the screenshots were probably part of a scheme orchestrated by Russian security services.

“Either it is true, and Leonid Nevzlin has gone mad, or it is an FSB provocation and a fake on which a lot of money has been spent … For perfectly understandable reasons, I lean towards the second,” Khodorkovsky said last month.

Khodorkovsky flew into Warsaw on Monday and met Polish prosecutors to share his own information about the case. In an interview on Wednesday, Khodorkovsky said he still believed the evidence was probably faked by Russian authorities.

I don’t think that these guys will be getting into power in Moscow any time soon.

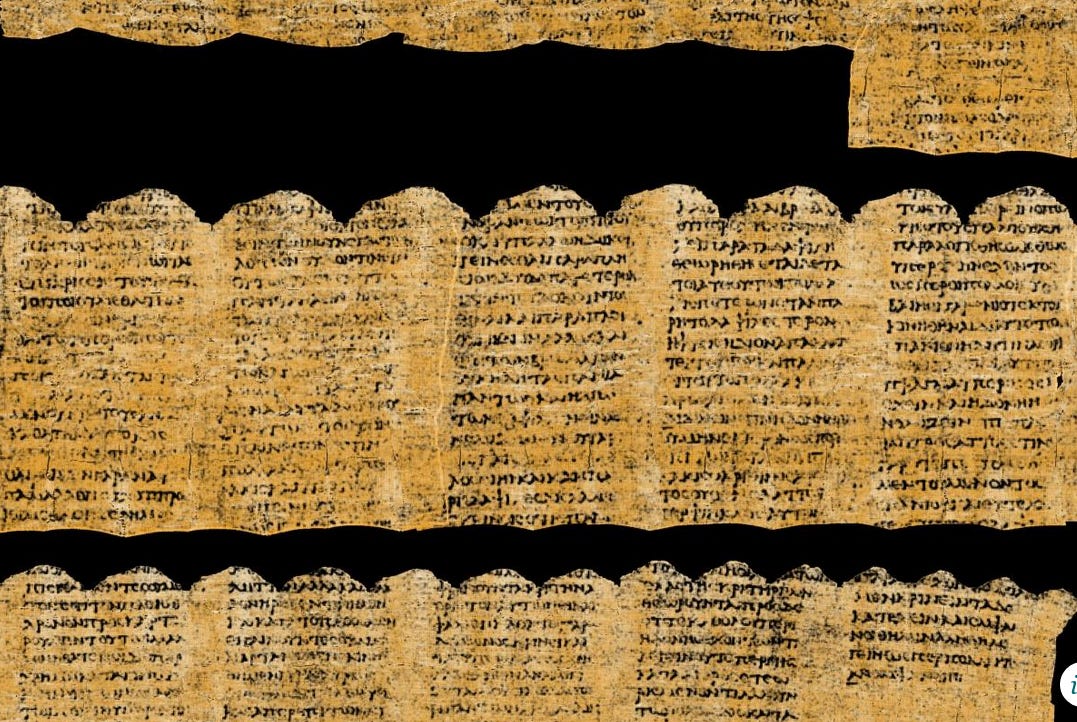

We end this weekend’s SCR with “doom scrolling”; the art of rediscovering ancient texts once thought lost to history:

The problem is more complex than the fact that many texts were lost to the annals of history. Most people just see the most recent translation of the Iliad or works of Cicero on the shelf at a bookstore, and assume that these texts have been handed down in a fairly predictable way generation after generation: scribes faithfully made copies from ancient Greece through the Middle Ages and eventually, with the advent of the printing press, reliable versions of these texts were made available in the vernacular of the time and place to everyone who wanted them. Onward and upward goes the intellectual arc of history! That’s what I thought, too.

But the fact is, many of even the most famous works we have from antiquity have a long and complicated history. Almost no text is decoded easily; the process of bringing readable translations of ancient texts into the hands of modern readers requires the cooperation of scholars across numerous disciplines. This means hours of hard work by those who find the texts, those who preserve the texts, and those who translate them, to name a few. Even with this commitment, many texts were lost – the usual estimate is 99 percent – so we have no copies of most of the works from antiquity.1 Despite this sobering statistic, every once in a while, something new is discovered. That promise, that some prominent text from the ancient world might be just under the next sand dune, is what has preserved scholars’ passion to keep searching in the hope of finding new sources that solve mysteries of the past.

And scholars’ suffering paid off! Consider the Villa of the Papyri, where in the eighteenth century hundreds, if not thousands, of scrolls were discovered carbonized in the wreckage of the Mount Vesuvius eruption (79 AD), in a town called Herculaneum near Pompeii. For over a century, scholars have hoped that future science might help them read these scrolls. Just in the last few months – through advances in computer imaging and digital unwrapping – we have read the first lines. This was due, in large part, to the hard work of Dr. Brent Seales, the support of the Vesuvius Challenge, and scholars who answered the call. We are now poised to read thousands of new ancient texts over the coming years.

A feel-good story! Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

And please don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already!

Another dispassionate piece on the Middle East. You are to be congratulated, Niccolo.

Lebanon was created on exactly the same basis as Israel. The French carved out a state for the Christians within the territory of the Mandate for Syria. They also created one for the Druze and the Alawites. These two were dissolved after anti-French uprisings. Lebanon was not caught up in these disturbances so the Lebanese state endured. The rationale for the three minoritarian states under French protection was recognition of the impossibility of non-Muslims retaining social or political equality under Muslim rule.

The British used the same authority to create a state for their Muslim clients, the Banu Hashemi (the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan) while reserving the remaining portions of the Mandate for Palestine for a Jewish state. The British went on to allow some Jewish migration but vetoed plans by Central European states (above all Poland and Hungary) to resettle Jews en masse. It is worth remembering that the first shots fired by UK forces in WW2 were aimed at Jewish refugees on a ship (Tiger Hill) seeking to land in Palestine. A few did make it, most were detained and returned to Europe. All of these were subsequently killed.

The issue has always been the legacy of the millet system and those aspects of the shariah derived from the Pact of Umar. The fate of the Jews across the Maghreb and the Mishraq (the Western and Eastern portions of the Arab world), as well as Turkey and Iran demonstrates the farsightedness and justice of the British and French approach in the period from 1917 till the 1920s. Ditto the more recent fate of the Christians in Iraq.

Lebanon's fate was sealed when outside forces (including the US) steered the Palestinians en masse into Lebanon after Black September in Jordan. Lebanon was used to ensure that the centre of gravity for the chaos within the region was placed as far as possible from the oilfields in the Gulf. Arafat was a wild card because he was a client of both sides in the Cold War, financed by Western allies like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, and (after adopting airline hijacking) the West itself. The West could not control Arafat and ended up sacrificing Christian interests within Lebanon to retain cooperation with the Saudis et al.

The abiding issue is the inability of the Lebanese ruling class to function as anything other than as compradors, whether these be Iranian, American, European.

The desperate urgency for us all is that the Western ruling classes are also becoming compradors for extranational forces (transnational corporations, drug cartels, rival superpowers). As we can see from the jihadis in the UK, the British ruling class now manage their domestic affairs with a view to Qatari, Iranian and Pakistani relationships. This is ironic...also ominous.