Saturday Commentary and Review #137

Mexico and State-Building, Only Biden 2024=Ukrainian Victory, Canada's Residential Schools Narrative-Building, Shelby Foote, Polanski's CHINATOWN and Conspiracies

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

It’s become a habit of mine to lead off these weekend SCRs with an essay or article that covers something of note in the news cycle. This weekend, I’ve decided to not do that, as I want to avoid repeating myself too often, and to not bore you, my dear readers.

On this of the Atlantic Ocean, Mexico is largely an afterthought. Most conversations about the country will revolve around tourism, as many Europeans will travel there. Mexico is also known for its pre-European history, and of course, for its cartel problem. What Mexico lacks in Europe is a constant presence like it has in the minds of North Americans. This is simply down to the fact that a very large ocean separates the two from one other.

I find it a fascinating country for many reasons, one of them being that they, like Canada, share a very long border with the world’s pre-eminent power. Living in the shadow of the USA means that they have had to be very, very careful so as to not upset their powerful neighbour. As Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau once stated, “sharing a border with the USA is like being a mouse next to an elephant”.

Presently, Mexico has a left-populist President in office, in a country where the state does not control all of its own recognized territory, due to the strength of the drug cartels that have divided the land among themselves. The amount of drugs that make their way across the border into the USA on a daily basis is colossal, yet the Americans (the Biden regime) have decided to open the border even wider, allowing migrants and drugs to flood in even faster than before. A strong border with Mexico seems like basic logic, but the powers-that-be in the USA are opposed to it for various reasons.

“Is Mexico a failed state?” is a common question asked these days. I won’t try to answer that question here, but I will share with you an interesting essay entitled “How Mexico Built a State”. What we will learn here goes beyond just Mexico, and has application to our present world and its current conflicts, and most of all, the conceit of western liberals who believe that a “one size fits all” approach to governance is viable globally.

The question:

Why can’t poor countries just mimic the common characteristics of rich countries and skip over all the toil and trial and error of the middle part?

Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock coined the phrase ‘skipping straight to Weber’ to refer to situations where international financial institutions like the World Bank or the IMF urge poor countries to catch up to rich ones by mimicking their institutions instead of recognizing that these institutions typically emerge only after a long process of trial and error.1 State development is difficult because it requires pushing in the right direction while constantly making win-win deals with existing power brokers at the temporary expense of the rule of law and impartial justice.

On state capacity (the subject of the essay):

There are lots of definitions of state capacity, but here I mean the ability of the Mexican government to enforce the laws in all of its territories, to be able to tax its people, and to formulate and enact policies. Not only does nineteenth century Mexico have all the ingredients for a good story, it also shows that some of the ways that countries do finally develop and governments build the capacity to rule are ones that no international financial institution would ever recommend.

Historical overview:

Mexico in the nineteenth century presents a dramatic example of this problem. Mexico suffered extreme political instability and strife in the nineteenth century. There were 800 revolts between 1821 and 1875. Between independence in 1821 and 1900, Mexico had 72 different chief executives, meaning that the average term was only a little more than one year long. Likewise, the country had 112 finance ministers between 1830 and 1863. In addition there were several invasions and secessionist movements.

The country also experimented with several different forms of government, including two empires (one headed by a French-backed, Austrian-born member of the Habsburg dynasty), one disputed period where there were presidents from both main parties, four republics, one provisional republic, and a long dictatorship. President Guadalupe Victoria was the first constitutionally elected president of the country, and the only one who would complete a full term in the first 30 years of independence.

Some other examples: There were four Mexican presidents in the years 1829, 1839, 1846, 1847, and 1853, while there were five in 1844 and 1855 and eight in 1833. Antonio López de Santa Anna, who was President of Mexico on ten separate occasions, was president four different times in a single year.

Mexico faced constant challenges to its sovereignty in the first 50 years of independence, from the secessions of Texas and Central America, to the secession attempts of the Yucatán, as well as numerous smaller rebellions.

And the threats were not all internal. Mexico lost one-half of its territory to the US in the mid-nineteenth century, an event that caused many Mexicans to lose even further respect for their government. In 1847, Mariano Otero, a leading Mexican jurist and utopian socialist of the period, explained its failure to resist US forces as being down to the fact that ‘Mexico did not constitute, nor could it properly call itself, a nation.’

Despite successfully gaining independence, Mexico was both a loser and a mess.

President/Dictator Porfirio Diaz turned the country around:

It wasn’t until the Porfiriato (1876–80 and 1884–1911), the period of time when Porfirio Díaz was president/dictator of Mexico, that the Mexican state began to have some capacity to fund policies and keep a lid on revolts against the central government. When Díaz first took power, there were still only five banks in Mexico, almost no manufacturing, and only 400 miles of railroad, in a country more than three times the size of France – which had 37,000 miles of track at that time. For 71 of Mexico’s miles, the trains were pulled by mules rather than steam engines.4

After decades of stagnation, federal revenues actually increased by five percent a year between 1895 and 1911, and this was the time when the Mexican economy began to grow. During Diaz’s tenure, manufacturing and oil production took off, banking became much more developed, and 17,000 miles of railroad tracks were laid, connecting all of Mexico’s largest cities.

These were revolutionary economic and political changes when compared to the stagnation and instability of the previous fifty years. Examining this kind of historical development more carefully allows us to understand and better help countries in their quest to establish the capacity to effectively rule, as well as to foster economic development.

The issue of scale:

First, the size of the territory matters for building state capacity. Throughout much of human history, city-states have been one of the most common types of state organization. Leaders of small regions can more easily solve the chicken and the egg problem. In cases where the population is small, the ruling elite will personally know more of the people serving under it, and find it easier to use rewards and punishment to control their behavior. Small regions are likely to be more homogenous, which empirically decreases the cost of providing public goods, perhaps because there is less conflict over what is to be provided, and to whom.5

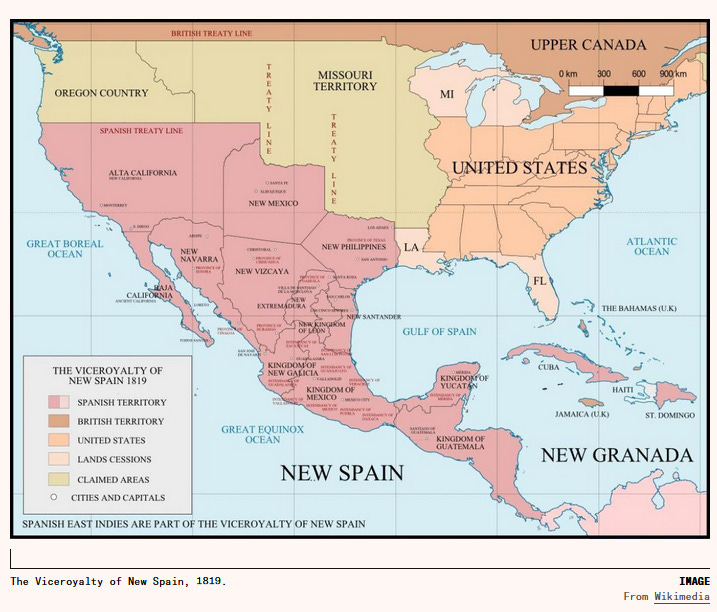

When dealing with a large country, however, a leader will need more impersonal mechanisms of control, and these are much harder things to create. Mexico at the time of independence was a very large country, including modern-day Mexico and Central America as well as much of the now-US Southwest.

To govern such a large country, the central government needed a strong army to make sure that the state governments paid their tax assessments. But it was exactly this reason that the state governments had little incentive to fund such a strong military.

The country was so large, and the roads so poor, that the central government did not even have a clear sense of the country’s borders, let alone full control of it. It became better mapped in the mid-nineteenth century and it was only then that the likes of General Antonio López de Santa Anna realized exactly how much territory the country had lost to the United States.6

Please note the bit about homogeneity and how it conflicts with today’s accepted position that “diversity is our strength”.

A lack of experience:

Second, experience matters. Regions that have experience with centralized state authority tend to be able to re-establish it more easily and quickly than regions without that history. Mexico had little experience with effective government and tried to impose a state on the populace from the top down.

There has long been a mythology in economic history that Spain was a strong, centralized state and ruled its colonies accordingly. In actuality, Spain had only two viceroys in the Americas, one for North America and one for South America. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was incredibly large, including modern Mexico and the territories mentioned above in the present-day United States and Central America, plus Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago, and even the Philippines, on the other side of the world.

Centralized administration of such a large territory necessitates a specialized and professional bureaucracy that can provide the leader with good policy advice as well as an administrative oversight of the different regions.

Money:

Third, developing state capacity requires money, something that the Mexican government was short of throughout much of the nineteenth century. It was short of money for a huge range of reasons, all of which boil down to unlucky shocks.

One issue was the war of independence. This war, which lasted from 1810–1821, was devastating to the Mexican economy and the state’s ability to collect taxes. There was an enormous amount of capital flight, which began even before the war.

The war also hurt mining. Many mines were flooded and destroyed during it. Silver output, previously the mainstay of the Mexican economy, fell to its lowest level in the 1820s, under half of what it was in the 1810s, and it was not until the 1860s and 1870s that the industry really began to recover.11 Silver mining had many links to other parts of the Mexican economy, which meant that the collapse of mining in the post-independence period also led to a reduction in production of other goods.

This is a fascinating analysis that you should read in full and then use to compare and contrast with other states. Mexico could have become another Haiti (a truly failed state), but didn’t. It is not Canada nor the USA either.

It is best practice to familiarize yourself with all sides of a debate when it comes to issues that interest you and/or affect you. When doing this, you will encounter distasteful sources, but we are all grownups here.

With this in mind, I am sharing with you an article written by a professor of strategic studies in Scotland, and published in that most neo-con/liberal interventionist of publications, The Atlantic Monthly. The subject deals with how a GOP win will negatively impact not just Ukraine in its war effort, but how it could also decimate the almost-century old alliance between the USA and Europe. Yes, it is alarmist.

The alarm:

Europe and the United States are on the verge of the most momentous conscious uncoupling in international relations in decades. Since 1949, NATO has been the one constant in world security. Initially an alliance among the United States, Canada, and 10 countries in Western Europe, NATO won the Cold War and has since expanded to include almost all of Europe. It has been the single most successful security grouping in modern global history. It also might collapse by 2025.

The cause:

The cause of this collapse would be the profound difference in outlook between the Republican Party’s populist wing—which is led by Donald Trump but now clearly makes up the majority of the GOP—and the existential security concerns of much of Europe. The immediate catalyst for the collapse would be the war in Ukraine. When the dominant faction within one of the two major American political parties can’t see the point in helping a democracy-minded country fight off Russian invaders, that suggests that the center of the political spectrum has shifted in ways that will render the U.S. a less reliable ally to Europe. The latter should prepare accordingly.

The reader will note all the assumptions made above.

Populism is anti-American:

The past few weeks have revealed that Trump’s pro-Russian, anti-NATO outlook isn’t just a brief interlude in Republican politics; suspicion of American involvement in supporting Ukraine is now the consensus of the party’s populist heart. During last week’s GOP presidential debate, Ron DeSantis and Vivek Ramaswamy—the two candidates most intent on appealing to the party’s new Trumpist base—both argued against more aid for Ukraine. DeSantis did so softly, by vowing to make any more aid conditional on greater European assistance and saying he’d rather send troops to the U.S.-Mexico border. Ramaswamy was more strident: He described the current situation as “disastrous” and called for a complete and immediate cessation of U.S. support for Ukraine. Ramaswamy later went even further, basically saying that Ukraine should be cut up; Vladimir Putin would get to keep a large part of the country.

The fear:

What leaders in Europe have to face, as a pro-Russia, anti-Ukraine position solidifies in the Republican Party, is the prospect of having to do most of the heavy lifting to help Ukraine win the war. That is no small task. Europe would have to expand its manufacturing capacities both for ammunition and other nuts-and-bolts military needs and for the more advanced systems, such as long-range missiles, that it would have to supply on its own.

If the United States simply abandons Ukraine a year and a half from now, there is no way whatsoever that Europe could make up for the loss of aid. But European governments would have to come up with ways to ameliorate that withdrawal. This would require tact and skill—and the preparations would have to start soon.

more:

Without committing itself to such comprehensive military planning, Europe could also find itself in an internal diplomatic crisis. Countries in the east (such as Poland and Romania) and North (such as the Baltic and Scandinavian nations) are desperate to see Russia defeated. But if Europe fails to embark soon on a unified, collective military-production plan, countries in the west and south that feel less threatened by Russian aggression might be inclined to follow the lead of a new American administration that backs away from Ukraine and tries to cut a deal with Russia. The result could be a legacy of bitterness and distrust at best, and a permanent fracturing of European cooperation at worst.

The obvious solution is to re-elect Biden and win Congress for the Democrats, because that “should be enough to see Ukraine through to a military victory…”.

Hopefully these scenarios won’t materialize. The election of a pro-NATO and pro-Ukraine U.S. president in 2024 should be enough to see Ukraine through to a military victory and peace deal (which would involve Ukraine’s admission into NATO), leading to security on the continent.

The subtext here is that only via American expansion on the European continent (through NATO) can “evil” be defeated and security be assured.

Back in 2016, current Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau described Canada as the “first postnational state”, whereby “there is no core identity, no mainstream….”. Instead, "There are shared values – openness, respect, compassion, willingness to work hard, to be there for each other, to search for equality and justice.”

Tearing down the foundations upon which Canada was built (British Empire, and British and French colonialism), he felt the need to go further. Canadian liberals are envious of the USA’s history of slavery where American liberals can self-flagellate endlessly to the applause and financial support of liberal elites. In Canada, liberals were determined to find and craft their own historical narrative of mistreatment of minorities.

Luckily (actually by design), stories from academia and media began to percolate regarding “mass graves of native children at residential schools”. Without a shred of physical evidence, Canadian liberals descended into spasms of self-flagellation, with PM Trudeau going so far as to accuse his own country of genocide. Even the Pope apologized for something that had yet to be proven. Dozens (if not more) of Catholic churches were set ablaze across the country in reaction to this scandal.

Two years later and shortly after the first series of excavations at these sites have conducted, not a single body has been found.

After two years of horror stories about the alleged mass graves of Indigenous children at residential schools across Canada, a series of recent excavations at suspected sites has turned up no human remains.

Some academics and politicians say it’s further evidence that the stories are unproven.

Minegoziibe Anishinabe, a group of indigenous people also known as Pine Creek First Nation, excavated 14 sites in the basement of Our Lady of Seven Sorrows Catholic Church near the Pine Creek Residential School in Manitoba during four weeks this summer.

The so-called “anomalies” were first detected using ground-penetrating radar, but on Aug. 18, Chief Derek Nepinak of remote Pine Creek Indian Reserve said no remains were found.

He also referred to the effort as the “initial excavation,” leading some who were skeptical of the original claims to think even more are planned.

“I don’t like to use the word hoax because it’s too strong but there are also too many falsehoods circulating about this issue with no evidence,” Jacques Rouillard, a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the Université de Montréal, told The Post Wednesday.

Falsehoods are no impediment to powerful historical narratives:

In May 2021, the leaders of the British Columbia First Nation Band Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc announced the discovery of a mass grave of more than 200 Indigenous children detected via ground-penetrating radar at a residential school in British Columbia. The radar found “anomalies” in the soil but no proof of actual human remains.

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify. To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths,” Rosanne Casimir, chief of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, said in a statement on May 27, 2021. (Casimir did not return a call from The Post this week.)

The band called the discovery “Le Estcwicwéy̓” — or “the missing.”

Pine Creek and Kamloops were among a network of residential schools across Canada, run by the government and operated by churches from the 1880s through the end of the 20th century. Experts say an estimated 150,000 children attended the schools.

But until last week, there hadn’t been any excavations in the alleged burial spots. There still have been no excavations at Kamloops nor any dates set for any such work to commence.

That didn’t stop many in Canada from painting a demonic picture of the residential schools and those who staffed them.

A reminder of the initial impact of these claims:

Assembly of First Nations Grand Chief RoseAnne Archibald told the BBC in August 2021 that the residential school policy was “designed to kill, and we’re seeing proof of that …”

Within days of the Kamloops announcement, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau decreed, partly at the request of tribal leaders, that all flags on federal buildings fly at half-staff. The Canadian government and provincial authorities pledged about $320 million to fund more research and in December pledged another $40 billion involving First Nations child-welfare claim settlements that partially compensate some residential school attendees.

and:

A number of writers, academics and politicians like Rouillard have come out cautioning against the claim that hundreds or thousands of children are buried at the school, but they have been labeled “genocide deniers” — even though many of the skeptics do not dispute that conditions at the schools were often harsh.

“The evidence does not support the overall gruesome narrative put forward around the world for several years, a narrative for which verifiable evidence has been scarce, or non-existent,” James C. McCrae, a former attorney general for Manitoba, wrote in an essay published last year.

McCrae resigned from his position on a government panel in May after his views on residential schools outraged Indigenous groups and other activists and politicians.

The kicker:

Eldon Yellowhorn, a professor and founding chair of the Indigenous studies department at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, told The Post last year that he too was cautious about the veracity of some of the more highly charged claims.

Yellowhorn, a member of the Blackfoot Nation, had been hired by Canada’s powerful Truth and Reconciliation Commission to search for and identify gravesites of Indigenous children at the residential schools. But he said then that many of the graves he found were from actual cemeteries and it wasn’t clear how they died.

This moral panic serves many political goals, and there are efforts underway to try and criminalize “residential denialism” in Canada. What is interesting is that no one disputes that some treatment was very harsh at these schools. That is not enough though; Canada needs its own historical narrative of genocide against non-white populations in order to whip itself and show its moral virtue to the rest of the world.

If you’re a Boomer or Gen X, there is a very, very good chance that you watched the Ken Burns documentary “The Civil War” when it aired on PBS in 1990 over the course of nine episodes.

If you were one of those people (I was), you were introduced to a genteel historian with a southern accent, one Shelby Foote. Of the overall nine hour length of the series, Foote alone had one hour of presence. An incredible raconteur, Foote regaled viewers with tales of heroism, elan, victory, and defeat. He came across as the stereotypical southern gentleman, something out of a Walker Percy novel.

You might have seen me reference him in this Substack over the years. I was gripped by his storytelling skills, and his voice still lingers in my mind. Two things that he said (and how he chose to say them) are permanently etched in my brain.

When asked if the Confederacy could have ever won the Civil War, he explained that the Union was always going to win, as it would have simply brought out its other arm from behind its back if the situation got too desperate

When asked what the impact of the Civil War was, he said that “before the war, people would say “the United States are”. After, they would say “the United States is.”

Hailing from Greenville, Mississippi, Foote never hid his pro-Confederacy views, but also viewed Lincoln as the “greatest President in US history”, something that alienated him from southrons.

I didn’t learn that he was part (half) Jewish until checking out his biography a few years ago. His father hailed from Scottish planters, his mother was of Viennese Jewish heritage. He hid his Jewish ancestry, but not fully. To me, his partial Jewish roots are just a historical curiosity and nothing more. He is in my eyes and incredible story-teller and historian, and a throwback to an era that is long gone now.

Blake Smith has written a very long piece on Foote, where he compares him to Foote’s literary idol, the Frenchman Marcel Proust, and also delves into his Jewish identity, or lack thereof. I have never read Proust, so I cannot comment on those portions of the essay. As mentioned, the Jewish angle is of little interest to me as well. For me, it’s his history of the US Civil War:

Foote did indeed identify with the South, and defend it with less the objectivity of a nonprofessional historian than with a political passion understanding of it as a victim of the American empire whose most compelling exponent—Abraham Lincoln—he unreservedly admired. His vision of history and politics, as the turns of the preceding sentence suggest, was far removed from the categories invoked by those today who would cancel or rehabilitate him. It hinges on a notion of honor—as what the artist seeks to win for himself and what the descendant owes to his forbears—that must have been particularly acute in a man who played the proud scion of Southern gentry to hide the other half of himself.

Honour was central to Foote’s storytelling in the PBS series.

Instead his literary monument is the Civil War trilogy, which, given his biography, it would be a grave mistake to imagine either as a bit of neo-Confederate hagiography or as objective history. It is, rather, a beautiful work of prose—and a powerful critique both of American politics and our conventional understandings of the relationship between politics and art.

In later life, after the publication of the trilogy, Foote sometimes expressed his regrets that during the crucial years of the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, he had kept out of politics, commenting little on the Civil Rights Movement and its connections back to the Civil War and Reconstruction. The latter he did bitterly criticize, saying on various occasions that the victorious United States had abandoned freed Black people to terrorism and peonage (inflicted, he did not perhaps sufficiently stress, by many of the same people—not least Nathan Bedford Forrest—whose military feats he had immortalized).

But The Civil War: A Narrative is a political book, one that sets the Civil War not—as we increasingly do today—as a central chapter in America’s long sinful history of white supremacy and the struggle to overcome it, but rather, indirectly though distinctly, with the Vietnam War as its unspoken background, as an epochal moment of American imperialism, to be at once regretted and, in the person of its great champion, Lincoln, celebrated.

An interesting point about Vietnam (although one which many will disagree with):

In a 1972 letter, as Vietnam was coming to its disastrous conclusion, Foote paralleled the senseless carnage of American bombing with the “Gotterdammerung” of the last days of the Civil War, when Sherman burned and pillaged his way across hundreds of miles of the South, and Grant and Lee locked themselves in months of trench warfare as Southern civilians starved. This was a “rehearsal for later glories, such as Vietnam.”

The “Jacobins of the GOP”:

Throughout The Civil War (although he has been criticized since for attending so much to military history that he neglected the motivations of the belligerents), Foote emphasized the radical aims of the “Jacobin” wing of the Republican Party. Already in 1862, many Northerners—and not only politicians—were calling for a total revolution in the to-be-conquered South. One Massachusetts colonel wrote his governor that the North must wield “permanent dominion” as a “regenerating, colonizing power … Schoolmasters, with howitzers, must instruct our Southern brethren that they are a set of damned fools in everything that relates to … modern civilization … This army must not come back. Settlement, migration must put the seal on battle.”

Today’s politically advanced Yankees who see the scourge of settler colonialism as one of the founding evils of America, coeval with slavery, would do well to consider that Reconstruction—their ancestors’ unsuccessful effort to undo slavery and its pernicious consequences—was conceived by its exponents, literally and explicitly and proudly, as a settler-colonial enterprise. To say the Civil War was a war of American imperialism, a campaign by the North—that is by the leading power of what we now call the “global north” of advanced industrial power—to absorb what was seen as a materially and morally backwards periphery is not to impose present-day categories on the past in a feat of paradoxically counter-woke presentism, but to cite the terms of the historical actors themselves. It should be difficult, although in their unreflecting bad faith so many progressives make it easy for themselves, to oppose both American imperialism—the self-righteous export of our own liberal-democratic regime and the imposition of our hegemony (when the former is not merely a mask for the latter) over the “global south,” from the Confederacy to Central America to Iraq and Afghanistan—and slavery, racism, and other evils, which after all are only ever extirpated by the violence of empire.

One last excerpt:

Foote famously said in interviews that he would have fought for the South had he been alive during the war, and would fight for it now—that is, would lose, and perhaps die, knowing he would lose—if the war were to be resumed, as a matter of “honor.” Tablet readers who recoil at this statement might reread Leo Strauss’ “Why We Remain Jews,” which argues that American Jews unable to believe in the religion of their forefathers, at least in the manner their forefathers had, who might indeed find it superstitious, outmoded, chauvinistic and lamentable, were bound nevertheless to continue to identify with it and defend it by just such a sense of “honor.”

Smith, the author of this essay, also writes in a grand, sweeping style….but it would be worth your time to read the whole thing, as he is a very interesting writer too.

We end this weekend’s Substack with a conspiratorial look at Roman Polanski’s CHINATOWN, not just one of the greatest noir films of all time, but one of the greatest movies ever made.

The writer of Chinatown, Robert Towne, won the Academy Award for this screenplay. He had written a trilogy actually. The first was Chinatown and focused on the California “water wars”. The second was about oil and the third, which was never made, was about land. California land manipulation and speculation is a fascinating subject and is quite topical given the recent suspicious and massively deadly fires in Lahaina on the Hawaiian island of Maui. It appears, similar to the way New Orleans real estate was plundered after Hurricane Katrina, that the Lahaina fire will follow the same disaster capitalist plan. As Chinatown makes clear, disaster capitalism is not a new phenomenon.

In one of the early scenes in the film we get to hear the story of a real dam, the Saint Francis, that failed and killed over 400 people in 1928. In the film the character of Hollis Mulwray is the engineer who built the failed dam. He is under immense pressure from odd segments of the public and an astroturft campaign carried out by unknown backers to build another dam using a similar design. IRL the dam was built at a location where the geological base was unstable because it was far cheaper than the other proposed location in the San Fernando Valley since “The Valley”, as we know it today, was already partially developed and it would cost the city a fortune to buy up all the property there. Fast, cheap and out of control is as American as Charles Manson and somehow always works out in favor of establishment power.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top of the page to like this entry. Use the share or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so. And don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already.

oww this hits very close to home since half my family is from MEXICO ( mom's side)

I've lived several years in the country, and I can tell another, overlooked situation.

Idiosyncracy.

Mexicans arent as a whole disciplined, work-oriented people (like Japanese or the anglos), preferring the easy way out (hence, how many are interested in "working" for the cartels) and handouts.

Its no suprise that the country has kinda thrived only under semi- or authoritarian govts ( porfirio diaz dictatorshsip, the PRI-semi authoritarian period 1930-2000).

Think of the country as that office full of workers that only deliver under a strict, tyrannical, bad tempered boss.

While the japanese and other 1st worlders are like workers that basically can do home office work and deliver, self-discipline embedded in them already.

Character matters, and national character ( something so many times overlooed, because, in the whacko worldview of the left, we are all "equal", like interchangeable Lego bricks) does too.