Saturday Commentary and Review #127

Patrick Deneen's Call For Regime Change, "Betrayal" of the White Working Class Male, AI to "Save Humanity"?, Elon Goes To China, Charles Brenner the "Longevity Skeptic"

One of the many paradoxes that is 21st century America is how some individual rights are being eroded as new groups are granted protection thanks to civil rights law.

Individual rights are central to understanding American history, whether political, legal, or cultural, and so on. They have informed every single aspect of American society from its founding, making the United States of America a liberal construct. It has long been my contention that this political liberalism that has at its basis the primacy of individual rights must reach its logical endpoint before a fundamental change can happen. The history of the USA is the history of the expansion of rights to its citizens, regardless of the anachronism of slavery that dominated the discourse of its early years, or other political movements that have sought to strip rights ever since (think Prohibition or the endless failed attempts at gun control).

The position that I have staked out makes me a fatalist regarding the trajectory of the USA, but it is worth paying close attention to those who challenge my fatalism, precisely those who believe that there is ‘another way’ for America and Americans. Past challengers included American communists, a group that was as ridiculous as Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists. Communism violated the the USA’s Prime Directive: “The Business of America is Business” while also taking the 180 degree stance regarding individual liberty. Nothing could be more un-American than communism.

Fast forward to our current century and we see growing attacks on individual liberties (specific ones) that have been taken for granted since the Bill of Rights was first introduced. “Hate Speech” is a ridiculous concept, but unfortunately is being championed by many in power in order to not only restrict who can speak, but especially to prevent challenges to prevailing elite narratives. This is but one of many examples of attacks on enshrined rights that are enjoyed by Americans today, attacks that are being waged by “illiberal liberals”.

As liberals increasingly (and paradoxically) use illiberal means to defend liberalism, others are questioning whether this increasing reliance on said means indicates that liberalism itself is running out of steam and that a new path forward must be carved out of existing institutions in order to save America. Foremost among these types is Notre Dame academic Patrick J. Deneen, the subject of a long profile in Politico:

….Deneen isn’t your typical intellectual. In 2018, Deneen burst onto the conservative scene with his bestselling book Why Liberalism Failed, a sweeping philosophical critique of small-L liberalism that earned praise from figures ranging from David Brooks to Barack Obama. Since then, he has risen to prominence as a major intellectual on the New Right, a loose group of conservative academics, activists and politicians that took shape in the years following Donald Trump’s election. The movement doesn’t have a unified ideology, but almost all its members have bought into the central argument of Deneen’s book: that liberalism — the political system designed to protect individual rights and expand individual liberties — is crumbling under the weight of its own contradictions. In pursuit of life, liberty and happiness, Deneen argues, liberalism has instead delivered the opposite: widening material inequality, the breakdown of local communities and the unchecked growth of governmental and corporate power.

In this profile, Senator J.D. Vance is mentioned a few times as a supporter of Deneen’s critique, going so far as to describe himself as “explicitly anti-regime”. This puts Deneen (and Vance) in the non-regime cohort of present US elites (see: here).

In Washington, Deneen’s thesis has found an eager audience among populist-minded conservatives like Vance, Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio who saw Trump’s election in 2016 as an opportunity to rebuild the Republican party around a working-class base, a combative approach to the culture war and an economic program that rejects free-market libertarian dogma.

Vance? Possibly, although I doubt it. Hawley and Rubio as anti-systemic? I don’t think so, but this is a minor quibble on my part for now. Allow me to jump ahead to the Vance bit:

During the panel that followed Deneen’s speech at Catholic, Vance identified himself as a member of the “postliberal right” and said that he views his position in Congress as “explicitly anti-regime.”

Back to Deneen:

But Deneen’s political vision doesn’t end with minor tweaks to the Republican Party’s agenda. As Deneen explained to his audience at Catholic, the major fault line in American politics is no longer the one between the progressive left and the conservative right. Instead, the country is split into two warring camps: “the Party of Progress” — a group of liberal and conservative elites who advocate for social and economic “progress” — and the “Party of Order,” a coalition of non-elites who support a populist agenda that combines support for unions and robust checks on corporate power with extensive limits on abortion, a prominent role for religion in the public sphere and far-reaching efforts to eradicate “wokeness.” In his new book Regime Change, out this month, Deneen calls on anti-liberal elites to join forces with the Party of Order to wrest control of political and cultural institutions from the Party of Progress, ushering in a new, non-liberal regime that Deneen and his allies on the right call “the postliberal order.”

That Deneen’s ideas are finding an audience in Washington speaks not only to the steady anti-liberal drift of the Republican Party, but also to the critical role that intellectuals like Deneen are playing in its embrace of alternatives to liberal democracy. Since Trump’s election, Deneen has become a hybrid scholar-pundit, lending philosophical heft and academic authority to the chaotic political forces transforming American conservatism. But as the title of his latest book suggests, Deneen’s role isn’t merely to describe the various strands of this populist tumult; it’s also to weave them together into a thread that populist leaders can use to bind the fractious elements of the post-Trump Republican Party into a new conservative movement — or, as some of Deneen’s critics charge, to lead them down the road to outright authoritarianism.

In short: a rejection of the liberal consensus that has dominated American politics for a long, long time. Remember: the primacy of individual rights is a liberal thing, much like free market economics (and globalism). Conservatives are liberals.

At the same time, this profile emphasizes how left wing thought has influenced Deneen (especially on subjects such as material wealth, class, and labour unions). This opens him up to critiques such as “Nazbolism” (the union of the hard left and hard right against the liberal centre, in the American context). Deneen will reject the incendiary charge of Nazbolism, but is more than happy to promote a ‘left-right synthesis’:

“I don’t want to violently overthrow the government,” Deneen said that day in his lecture at Catholic, addressing critics who might interpret his work as a call for a never-ending Jan. 6. “I want something far more revolutionary than that.”

more:

In 1949, the liberal literary critic Lionel Trilling surveyed the state of American politics and concluded that “liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition” in the United States. “It is the plain fact that nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation,” he wrote. In the place of a reactionary intellectual tradition, there were merely “irritable mental gestures which seem to resemble ideas.”

I was reminded of this passage when I read Deneen’s new book, and when I spoke to him earlier this spring, I asked him if he agreed with Trilling’s conclusion.

“That’s right,” said Deneen. “Whether it’s on the right or the left, there’s no one who’s been arguing for a tradition that says, ‘What a lot of people in this country need is just a lot more sort of predictability in their lives, a kind of continuity in which their lives are not being constantly disrupted.’”

The profile makes mention of how Deneen has been influenced by communitarianism, and how Christopher Lasch’s critique of liberalism has informed his own over the years:

McWilliams and Lasch also played a decisive role in shaping Deneen’s early political outlook, which tended instinctively toward the left. Although both men were sympathetic to conservative cultural concerns, they were steeped in the literature and practice of post-war Marxism, and Deneen inherited their tendency to analyze politics in a leftist framework — to think about political power as the dynamic exchange between people and elites, material conditions and ideological constructions, state coercion and popular resistance.

“To the extent that Patrick was really close with and moved by my father’s politics, those were unapologetically left politics,” said McWilliams Barndt, who met Deneen while he was at Rutgers and later studied under him as a graduate student at Princeton. “When I was working with him, I always thought of him as somebody who was more on the left than on the right.”

Elitism, phony liberalism, and John Rawls:

At Princeton, Deneen found himself in a dramatically different intellectual world than the one he had come to love at Rutgers. For one thing, many of his colleagues on the politics faculty were admirers of the liberal philosopher John Rawls, a primary intellectual opponent of communitarianism. Deneen sensed in his colleagues’ work a hostility to the religiously inflected political ideals that communitarians like McWilliams promoted — especially the Catholic teachings that Deneen had grown up with in Windsor.

But even more troubling to Deneen was the air of casual elitism that pervaded Princeton’s campus. Although his colleagues and students were fluent in the language of liberal egalitarianism, they seemed more interested in hiding behind critiques of inequality than they were in using them to understand their own elite status, Deneen told me.

“At some level, it was like, ‘Who are these people? Do they really believe this?’” he recalled. “I began to see the kind of egalitarian shroud operating as a new way in which an oligarchy was shrouding its privilege.”

Deneen moved first to Georgetown, and then decamped later to Notre Dame, where he is at present.

In the wake of Trump’s election, commentators on both the left and the right had jumped to explain the political conditions around the country as a failure of the liberal promise, but Deneen flipped that formulation on its head. The alienation and anger that Americans felt were a direct consequence of liberalism’s successes, not its failures, Deneen argued. The Western world had not run out of oil; it had run out of faith in progress. Liberalism itself was the problem.

Why Liberalism Failed caught fire. Within a month, the New York Times ran a lengthy review and three separate columns about it, and Barack Obama included it on his list of favorite books of 2018. A paperback edition was released less than a year later, and the book was quickly translated into over a dozen languages.

Politico being Politico:

But the wave didn’t stop there. In the fall of 2019, Deneen was teaching in London when he received an invitation from the Hungarian government to travel to Budapest and meet with the country’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán — a self-proclaimed defender of “illiberal democracy.” In the presidential palace on the banks of the Danube River, he and Orbán talked about Why Liberalism Failed and discussed Hungary’s family policy, which includes interest-free loans to heterosexual couples planning to have children and up to three years of maternity benefits for new mothers.

When news of the meeting made it back to the United States, Deneen’s critics swiftly denounced him for playing footsie with Orbán’s government, which has targeted independent journalists, banned LGBTQ-related sex education, turned away asylum seekers and amended Hungary’s election law to consolidate its control on power. Among those most baffled by Deneen’s embrace of Hungary’s prime minister were his friends and former classmates from Rutgers.

“I was actually stunned,” said Romance. “Our mutual mentor, Carey McWilliams, would never have had a bit of time for a guy like Orbán.”

“Common-good conservatism” and its rejection of nationalism:

Deneen’s early efforts to describe this vision brought him into contact with a small group of like-minded Catholic thinkers, including the Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule, the political theorist Gladden Pappin, the theologian Chad Pecknold and the conservative journalist Sohrab Ahmari. The group began trading messages in a group chat, and they soon started co-writing essays and blogs laying out their vision across law, politics, economics and theology. In November 2021, Deneen, Vermeule, Pappin and Pecknold launched a Substack newsletter called “The Postliberal Order” to serve as a digital home for their ideas. In March 2022, Ahmari followed suit with a small online publication called Compact, a self-proclaimed “radical American journal.”

Within the cohort of postliberal thinkers, Deneen has focused on articulating a vision of what he calls “common-good conservatism,” an alternative to the so-called “liberal conservatism” that has dominated right-wing movements around the world since the onset of the Cold War. On economic matters, Deneen’s “common good” approach rejects free market fundamentalism and endorses nominally “pro-worker” policies to strengthen unions, combat corporate monopolies and limit immigration. On social questions, it is explicitly reactionary, opposing “progressive” ideas about race, gender, and sexuality and supporting policies to promote heterosexual family formation. For instance, Deneen opposes gay marriage, denounces “critical race theory” as an effort to divide the working classes, and generally supports policy to make it more difficult for married couples to get divorced.

Philosophically, common-good conservatism is premised on the idea that there is a universal “common good” that transcends the interests of any particular community or constituency — a belief with deep roots in Catholic social teaching. It rejects pluralism, as well as conservatives’ traditional emphasis on limited government, arguing that a strong central government should endorse a socially conservative vision of morality and enforce that vision in law. In contrast to the “national conservatism” that’s also gaining traction on the populist right, Deneen’s vision of conservatism is also skeptical of nationalism, which the postliberals view as a byproduct of the liberal order.

“It’s not that any of us is anti-nation, but there has to be something both less than and more than the nation,” Deenen told me — local communities rooted in specific places and trans-nation communities rooted in a specifically Catholic notion of universal humanity.

All of this is worthy of a standalone treatment from myself, something that I will do later this summer. I’ll save my views on this positions for then. In the meantime, Deneen continues to ruffle feathers, especially considering how his new book is provocatively titled: “Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future”.

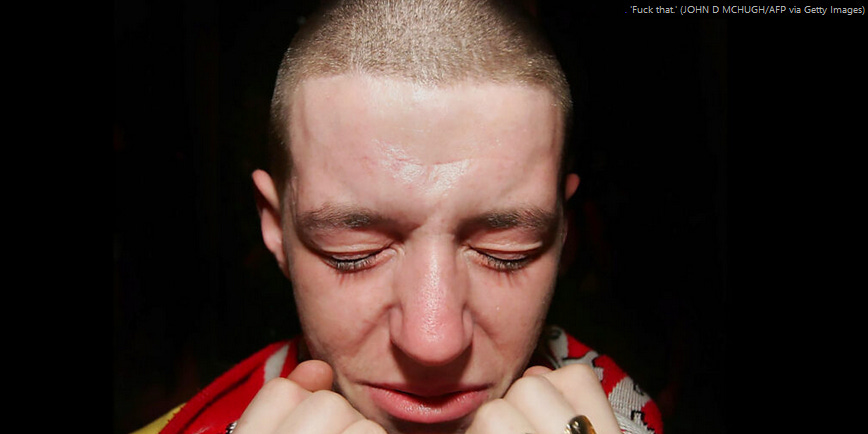

Even though Deneen is assigned to the right side of the populist column, much of his critiques of liberalism are shared by (and more often than not, originate from) the left side of the ledger. Case in point: this piece from the notorious Scottish author of Trainspotting, Irvine Welsh in which he claims that the white working class has been ‘betrayed’ by UK elites (same as it ever was):

Cards on the table: I’m a rampant opponent of white, bourgeois, male privilege. Events such as the Coronation, or another Biden-Trump stand-off, pull this lunacy into sharp focus. Yes, these ludicrous and deranged media-driven circuses may have little to do with women, black, Asian, gay or trans people. But let’s get this straight: they have absolutely fuck all to do with white working-class men either.

According to liberal conventional wisdom, we are in a post-industrial, post-imperial society where shouty (white) men can no longer trumpet their entitled assumptions unchallenged, and perhaps even have to stand in line. Well, if that’s truly the case, thank fuck for it. After all, imperialism and the patriarchy cost a lot of lives, and gave us wars, bad politics and bad art. And nothing’s changed.

There is more I disagree with in this ranting essay than that with which I agree, but it’s worth sharing to gain a perspective on class politics that most of us are not exposed to. There will be bits in this essay that sound ridiculous to you (most likely because they are), so for those of you who will think this, hold your nose and read it anyway, as it does have some value.

Because some sections of the white working class bought into the reductive neoliberalism of unrestrained capitalism through the Thatcher-Reagan revolution, so the entire group was written off. In the “hierarchy of the oppressed” so beloved of intersectional theory, a (white) penis in the underpants is more important than the lack of an arse in the trousers in determining your place in the world.

So, what excludes white working-class men from this LGBT intersectional paradigm? It can’t be race, as white women are permitted. It can’t be class, as working-class women and black men are allowed in. It can’t even be sex/gender, as gay or bisexual white working-class men and women are included. But perversely, white proletarian men are lumped in with their bourgeois “brethren”; outsiders in this rainbow-coloured festival of the oppressed.

Welsh is going to bat for male white proles in a very idiosyncratic way (to most of us, at least), something that he is very correct in doing. The idea that a lumpenprole in Cincinnati is an oppressor is nonsense, but here we are today.

The decline of class politics and its replacement by the schisms of identity is an integral part of the neoliberal order. After all, one unites and the other divides. The class war was won by the elite in Britain, probably as far back as Orgreave in the 1984 miners’ strike, when organised labour was crushed. Today, capital rules supreme, steadfastly tightening its hold, aided by a rapacious individualism that has now tipped into a demented narcissism, and a technology concentrated in the hands of corporations and its co-opted governments.

There is a growing echo of people who seem to be pushing the notion that identity politics is a product of the capitalist class. I take issue with this for the simple fact that it finds its origins in academia, not in the for-profit corporate world. Academia informed policy, which became law, and law created legal liability that corporations are exposed to. Welsh, like many of the critics of “wokeness” on the left, has it ass-backwards.

The fraying bonds of community:

In Britain, I believe that the traditional working man — of all colours — has had a bad rap. Recently, I was out with some old pals, and we were talking about how we’ve stayed close friends down the years, despite life, love and work taking us off in varying directions. One friend went on at length about how his partner and her friends were quite surprised at the continuing bond between us all. It’s a recurrent theme with women I know, who ask, perhaps not unjustly: how can you still be bothered with each other?

Men, whose camaraderie can seem frivolous, built on drinking, football and laughing at each other’s embarrassments, paradoxically tend to stick together down the years more than women, who talk of weightier, more emotional subjects. Several years ago, following a relationship breakdown scenario, I went through a phase where I felt like I was done with male company. I decided I could do without the gung-ho nature of the archetypal male response to such events: “Forget her. They’re all the same. Get another round up. I’ve left a line out for you in the toilets.” As a result, I basically surrounded myself with my women friends. Not for the first time, they were the ones offering real support and genuine insight into my predicament.

Then you realise: it’s not about thesis and antithesis. There’s always got to be room for a synthesis of different ideas and values. Once more, I’m appreciating the narrow, lazy affirmation that belonging to a mob of men can offer. The best thing about being a man of my generation is that we’re allowed to get the fuck out of the house. Now I feel for youth who don’t do this so much — they really don’t know what they are missing. When they do, the experience is invariably packaged for them. The biggest indictment you can offer our current dystopia is that we’ve created a society where the old pity the young. That’s just not right.

Masculinity (as well as femininity) is tied to our lost sense of community. As pubs and clubs close down across the country, teenagers are more likely to spend their evenings on Instagram, TikTok, playing video games or on some dubious porn forums than getting drink from the offie and messing around in the park or on abandoned railway lines. A social vacuum has been created at the same time as a dumbed-down visceral communication system has emerged. This creates a place where someone as pathetic as Andrew Tate can gain a limited sphere of influence. The emergence of such characters would have been impossible in the Nineties. They would have been dismissed as ludicrous wankers in a truly contested, democratic street culture, as opposed to the top-down media one we now live in. Now a noncey, supermarket transgression has gained a foothold, appealing to an entire lost generation of anxious, isolated teenage bedroom wankers, brimming with the sleazy narratives of onscreen porn.

Increasing atomization as a function of technology is a valid critique. Score another one for Welsh.

In their growing absence, the neoliberal state has gutted everyone’s lives of meaning — to the extent that we have little to cling to other than a narcissistic, media-constructed sense of who we are and our supposed entitlement to avoid personal discomfort at all costs. Thus, through toxic social media platforms, proponents of various identities get to sling all sorts of mud at each other, devoid of any social setting and real human interaction. Generally, it’s an inconsequential battle, in which people are afforded the keyboard warrior’s licence — rewarded by the dopamine hits — to abuse each other with relative impunity. The objective of the game is to goad the other party into an overreach and a subsequent pile-on, with an attendant Twitter ban or, the great weapon of our times, “cancellation”. Generally, however, in those futile wars, no party claims a feasible victory. Nonetheless, the participants are rarely shy of pompously deploying tiresome, overdramatic dictums declaring their cause or viewpoint to be “on the right side of history”.

This nonsense benefits only the continuation of the current bankrupt system. The establishment’s economic, financial and social elites once starved people into compliance; now it lures them into pointless shouting matches, allowing them to stupefy themselves in the process.

Welsh is criticizing those on his side of the political spectrum, but he is glossing over the vast gulf that exists between the male white prole and the identity groups who gleefully cheer on their destruction, the same identity groups that he insists white proles should ally themselves to in order to fight “neoliberal oppressors”.

What we certainly are allowed to do, is to be nostalgic. The system plays on our need to make sense of our existence by processing our past, but only in a way that all conflict is taken out of it. Thus, our need to validate our lives in a fake “golden age” haze becomes a de facto endorsement of a system that has limited the potential of those lives. It encourages us to sit around crying into our beer about how things ain’t what they used to be, reconstructing a collective rose-tinted past designed to sustain us in our dotage, while ensuring this state creeps ever closer as mindless aphorisms — ubiquitous, circular — rot our brains.

You can never go home again.

At the same time, Irvine, you cannot paper over the fundamental differences in vision as to how society should be run by appealing to something as brittle as ‘class unity’. A class-based politics is in itself an appeal to nostalgia too.

Judging by recent editions of the Saturday Commentary and Review (SCR), many of you are really, really into discussing and debating Artificial Intelligence (AI) and what it holds for our collective future. I am thinking quite a bit about this subject too, but am withholding opinion for two reasons:

there is A LOT to think about, especially the ramifications as to how it will change our lives (particularly how we sort and process information inside of our own heads)

I don’t understand enough of it to give an informed opinion

What you will find me doing is sharing informed opinions with you on this topic, whether they be negative, positive, or a mix of both. With this in mind, I would like to share with you a positive take on AI courtesy of friend of this Substack, Marc Andreessen. He is of the view that AI “might” save humanity.

First, a short description of what AI is: The application of mathematics and software code to teach computers how to understand, synthesize, and generate knowledge in ways similar to how people do it. AI is a computer program like any other – it runs, takes input, processes, and generates output. AI’s output is useful across a wide range of fields, ranging from coding to medicine to law to the creative arts. It is owned by people and controlled by people, like any other technology.

A shorter description of what AI isn’t: Killer software and robots that will spring to life and decide to murder the human race or otherwise ruin everything, like you see in the movies.

An even shorter description of what AI could be: A way to make everything we care about better.

I have no doubt that some of you are already groaning, concluding that Marc is being either pollyannish in his views, or self-serving, or both. Nevertheless, we will continue marching through his essay in order to hear him out:

What AI offers us is the opportunity to profoundly augment human intelligence to make all of these outcomes of intelligence – and many others, from the creation of new medicines to ways to solve climate change to technologies to reach the stars – much, much better from here.

AI augmentation of human intelligence has already started – AI is already around us in the form of computer control systems of many kinds, is now rapidly escalating with AI Large Language Models like ChatGPT, and will accelerate very quickly from here – if we let it.

Marc goes on to list several examples of how AI will make things better, of which I will highlight a few select ones:

Every scientist will have an AI assistant/collaborator/partner that will greatly expand their scope of scientific research and achievement. Every artist, every engineer, every businessperson, every doctor, every caregiver will have the same in their worlds.

Every leader of people – CEO, government official, nonprofit president, athletic coach, teacher – will have the same. The magnification effects of better decisions by leaders across the people they lead are enormous, so this intelligence augmentation may be the most important of all.

Productivity growth throughout the economy will accelerate dramatically, driving economic growth, creation of new industries, creation of new jobs, and wage growth, and resulting in a new era of heightened material prosperity across the planet.

Scientific breakthroughs and new technologies and medicines will dramatically expand, as AI helps us further decode the laws of nature and harvest them for our benefit.

The creative arts will enter a golden age, as AI-augmented artists, musicians, writers, and filmmakers gain the ability to realize their visions far faster and at greater scale than ever before.

The current panic about super-powered AI:

We hear claims that AI will variously kill us all, ruin our society, take all our jobs, cause crippling inequality, and enable bad people to do awful things.

What explains this divergence in potential outcomes from near utopia to horrifying dystopia?

Historically, every new technology that matters, from electric lighting to automobiles to radio to the Internet, has sparked a moral panic – a social contagion that convinces people the new technology is going to destroy the world, or society, or both. The fine folks at Pessimists Archive have documented these technology-driven moral panics over the decades; their history makes the pattern vividly clear. It turns out this present panic is not even the first for AI.

Now, it is certainly the case that many new technologies have led to bad outcomes – often the same technologies that have been otherwise enormously beneficial to our welfare. So it’s not that the mere existence of a moral panic means there is nothing to be concerned about.

But a moral panic is by its very nature irrational – it takes what may be a legitimate concern and inflates it into a level of hysteria that ironically makes it harder to confront actually serious concerns.

And wow do we have a full-blown moral panic about AI right now.

This moral panic is already being used as a motivating force by a variety of actors to demand policy action – new AI restrictions, regulations, and laws. These actors, who are making extremely dramatic public statements about the dangers of AI – feeding on and further inflaming moral panic – all present themselves as selfless champions of the public good.

But are they?

And are they right or wrong?

“Baptists” vs. “Bootleggers”:

Economists have observed a longstanding pattern in reform movements of this kind. The actors within movements like these fall into two categories – “Baptists” and “Bootleggers” – drawing on the historical example of the prohibition of alcohol in the United States in the 1920’s:

“Baptists” are the true believer social reformers who legitimately feel – deeply and emotionally, if not rationally – that new restrictions, regulations, and laws are required to prevent societal disaster.

For alcohol prohibition, these actors were often literally devout Christians who felt that alcohol was destroying the moral fabric of society.

For AI risk, these actors are true believers that AI presents one or another existential risks – strap them to a polygraph, they really mean it.

“Bootleggers” are the self-interested opportunists who stand to financially profit by the imposition of new restrictions, regulations, and laws that insulate them from competitors.

For alcohol prohibition, these were the literal bootleggers who made a fortune selling illicit alcohol to Americans when legitimate alcohol sales were banned.

For AI risk, these are CEOs who stand to make more money if regulatory barriers are erected that form a cartel of government-blessed AI vendors protected from new startup and open source competition – the software version of “too big to fail” banks.A cynic would suggest that some of the apparent Baptists are also Bootleggers – specifically the ones paid to attack AI by their universities, think tanks, activist groups, and media outlets. If you are paid a salary or receive grants to foster AI panic…you are probably a Bootlegger.

The problem with the Bootleggers is that they win. The Baptists are naive ideologues, the Bootleggers are cynical operators, and so the result of reform movements like these is often that the Bootleggers get what they want – regulatory capture, insulation from competition, the formation of a cartel – and the Baptists are left wondering where their drive for social improvement went so wrong.

We just lived through a stunning example of this – banking reform after the 2008 global financial crisis. The Baptists told us that we needed new laws and regulations to break up the “too big to fail” banks to prevent such a crisis from ever happening again. So Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, which was marketed as satisfying the Baptists’ goal, but in reality was coopted by the Bootleggers – the big banks. The result is that the same banks that were “too big to fail” in 2008 are much, much larger now.

So in practice, even when the Baptists are genuine – and even when the Baptists are right – they are used as cover by manipulative and venal Bootleggers to benefit themselves.

And this is what is happening in the drive for AI regulation right now.

Marc also lists six risks to AI, ending with one in which the USA cannot surrender competitiveness to the Chinese who are already barrelling full-steam ahead with the technology.

What is to be done?

I propose a simple plan:

Big AI companies should be allowed to build AI as fast and aggressively as they can – but not allowed to achieve regulatory capture, not allowed to establish a government-protect cartel that is insulated from market competition due to incorrect claims of AI risk. This will maximize the technological and societal payoff from the amazing capabilities of these companies, which are jewels of modern capitalism.

Startup AI companies should be allowed to build AI as fast and aggressively as they can. They should neither confront government-granted protection of big companies, nor should they receive government assistance. They should simply be allowed to compete. If and as startups don’t succeed, their presence in the market will also continuously motivate big companies to be their best – our economies and societies win either way.

Open source AI should be allowed to freely proliferate and compete with both big AI companies and startups. There should be no regulatory barriers to open source whatsoever. Even when open source does not beat companies, its widespread availability is a boon to students all over the world who want to learn how to build and use AI to become part of the technological future, and will ensure that AI is available to everyone who can benefit from it no matter who they are or how much money they have.

To offset the risk of bad people doing bad things with AI, governments working in partnership with the private sector should vigorously engage in each area of potential risk to use AI to maximize society’s defensive capabilities. This shouldn’t be limited to AI-enabled risks but also more general problems such as malnutrition, disease, and climate. AI can be an incredibly powerful tool for solving problems, and we should embrace it as such.

To prevent the risk of China achieving global AI dominance, we should use the full power of our private sector, our scientific establishment, and our governments in concert to drive American and Western AI to absolute global dominance, including ultimately inside China itself. We win, they lose.

And that is how we use AI to save the world.

It’s time to build.

Have at it, gang!

I recently wrote about the new Industrial Policy that has been proposed by Biden’s National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan. In it, I raised what I think is the most important question to pose to Sullivan: can he get buy-in from America’s corporate leaders for this plan?

Some answers are coming in much sooner than I expected, with a big “NO” from Elon Musk first and foremost, as he traveled to China recently to “double down” on producing EVs there, outright rejecting the call to either “re-shore” or “friendshore” US industry already in that country:

As the global economic intelligentsia debates how to “decouple” or “de-risk” from China, Elon Musk clearly didn’t get the memo.

The Tesla founder was feted like a returning king in Beijing this week. From the moment his private jet arrived on Tuesday, Musk is reportedly being called “Brother Ma,” putting him in rarified league with Alibaba billionaire Jack Ma.

Big takeaways:

There are many takeaways from Musk’s first China visit in three years. One is that not everyone is decoupling from China, least of all the globe’s most influential electric vehicle (EV) evangelist and owner of Twitter. Another: the future of EV production and innovation is shifting toward Asia’s biggest economy.

Yet the most important one may be how Beijing is putting out a huge welcome mat for foreign chieftains – from Musk to JPMorgan Chase’s Jamie Dimon – to signal that China really is open for business again.

The perception that China is becoming hostile toward foreign capital intensified after Ma ran afoul of Xi Jinping’s regulators in late 2020.

In March, China’s leader installed a new premier, Li Qiang, to take the lead in changing that narrative. And what better way than Musk visiting China and reaffirming his commitment to producing more Teslas in mainland factories?

“Good business”:

Now, here is Musk, controversial as he is, hinting at an even bigger production presence in China. In 2022, Tesla contributed roughly one-quarter of Shanghai’s overall total automotive production.

The next objective for local governments around China: angling for closer ties with Tesla to win some of those jobs as Musk looks to expand his autonomous driving fleet and sales to Chinese consumers.

It’s just what Li’s image makers might have hoped for as Tesla looks to “aggressively focus on building out its China footprint,” says analyst Daniel Ives at investment firm Wedbush.

Musk continues to taunt and challenge current US elites:

Musk is also giving Xi and Li a big public relations win in another way. At his meeting Tuesday with Foreign Minister Qin Gang, Musk gave the thumbs down to Washington’s decoupling from China strategy. Musk said, effectively, that the relationship between the two biggest economies is too symbiotic to fail.

Musk is not the only one either:

This is music to Li’s ears as China welcomes a who’s-who of multinational company chieftains. In recent days, top officials from Starbucks Corp, Jardine Matheson, Franklin Templeton and UK chip software giant Arm Ltd dropped by. Later this month, Nvidia Corp CEO Jensen Huang is reportedly coming to town.

The frenetic pace of these meetings comes as China’s foreign direct investment experiences an ill-timed U-turn. In the first three months of the year, roughly US$30 billion zoomed away from China. Stock investors are pivoting elsewhere, too. Since its 2021 high, the MSCI China Index has lost more than half of its value.

Elon and gang are rejecting the proposed new Industrial Policy, which means that Biden is running the risk of starving himself of some corporate benefactors going into 2024. Which candidate will Corporate America support next year?

We end this weekend’s Substack with a look at Charles Brenner, a biochemist from Los Angeles who is calling “bullshit” on longevity research:

At the Longevity Investors Conference last October in Switzerland, speakers described breakthrough therapies being developed to manipulate genes for longer lifespans. Swag bags bestowed pill bottles promising super longevity, stirring hopes for centuries of youth.

Then Charles Brenner took the stage. The biochemist from City of Hope National Medical Center, in Los Angeles, addressed these ideas and treatments one by one, picking them apart, explaining that they’re based on faulty research. We can’t stop aging, he told the crowd. We can’t use longevity genes to stay young because getting older is a fundamental property of life.

Scanning their faces, he saw puzzled expressions. Mission accomplished.

Over the past year, Brenner has been challenging life-extension theories on Twitter, YouTube, and the conference circuit, where he’s been introduced as the “longevity skeptic.” He resembles an eagle—he’s hairless on top with an aquiline nose and penetrating gaze—an appearance that goes well with his astute intellect, tenacity, and willingness to fly solo as one of the most boisterous critics of anti-aging science.

Brenner tells people the reasons for suspicion date back to Herodotus’ made-up account of the Fountain of Youth in 425 B.C. Some things never change, he says, even as the field of aging research has picked up scientific momentum in recent years. Investments in longevity startups are predicted to jump from $40 billion to $600 billion in the next three years. Lured by funding from digital age tycoons such as Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel, top scientists are aligning with companies to advance their work.

Brenner is critical of several big promises emanating from these companies and researchers, such as claims that cellular reprogramming could halt aging. He dismisses speculation from gerontologist Aubrey de Grey that anti-aging therapies will keep us above ground for multiple centuries. But perhaps no scientist in the field of aging has attracted Brenner’s criticisms more than David Sinclair, the Harvard biologist and bestselling author of Lifespan: Why We Age and Why We Don’t Have To. Sinclair is working on therapies that he says could slow human aging to a crawl, allowing us to live decades longer.

At best, Brenner says, scientists can develop therapies that maintain the health of older people and help keep them out of the hospital—an increasingly important goal as the average age in the United States and elsewhere keeps climbing. Brenner is tackling this problem as the chief scientific advisor of a bioscience company called ChromaDex, which markets supplements for “healthy aging.” But believing we can rewrite the operating manual for lifespan itself, Brenner told me, is like “believing in the tooth fairy.”

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

Note: As mentioned previously, I have now raised the price for a subscription to this Substack to $7/month. For those wanting to save some money, I will keep the yearly price at its current $50/year until later this month.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the very top of the page to like this entry and use the share button to share this across social media.

Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so (be nice!), and please consider subscribing if you haven't done so already.

...and don't forget to join me on Substack Notes - https://niccolo.substack.com/p/introducing-substack-notes

Further to my previous comments, Deneen's post-liberalism is an exercise in nostalgia. The civic nationalism of the past cannot be reconstructed because the ethnic character of North America has been transformed by Civil Rights and mass migration. There are now vast constituencies that have a direct stake in the constitutional/legal status quo that has established race preferences that deprioritise whites to the advantage of their fellow-citizens.

Deneen needs to address the elephant in the room: the question of whether or not whites deserve to be denied collective political agency as whites.

No serious project of national renewal can work until it addresses the issues the current regime dare not acknowledge beyond making accusations of 'white supremacy' against perceived enemies.