Saturday Commentary and Review #112

France vs. 'Le Wokisme', "USA took out Nordstream 2", US Media Failures and Complicity Over "Trump-Russia", Irish Anti-Migrant Protests, The Sons of Chad

The election of Barack Obama as President of the United States of America in 2008 was supposed to usher in a “post-racial era”. By the time his second term kicked off, that notion was relegated to the dustbin of history as the rise of “Wokeness” took America in the opposite direction: hyper-racialism. Where MLK asked that “…people not be judged by the colour of their skin…”, this new political culture assigned hard-coded values to individual people based on their skin colour (alongside other group identities). There is no need to explain just how successful this new political culture has been in the USA over the past decade, as all of you are already aware of it.

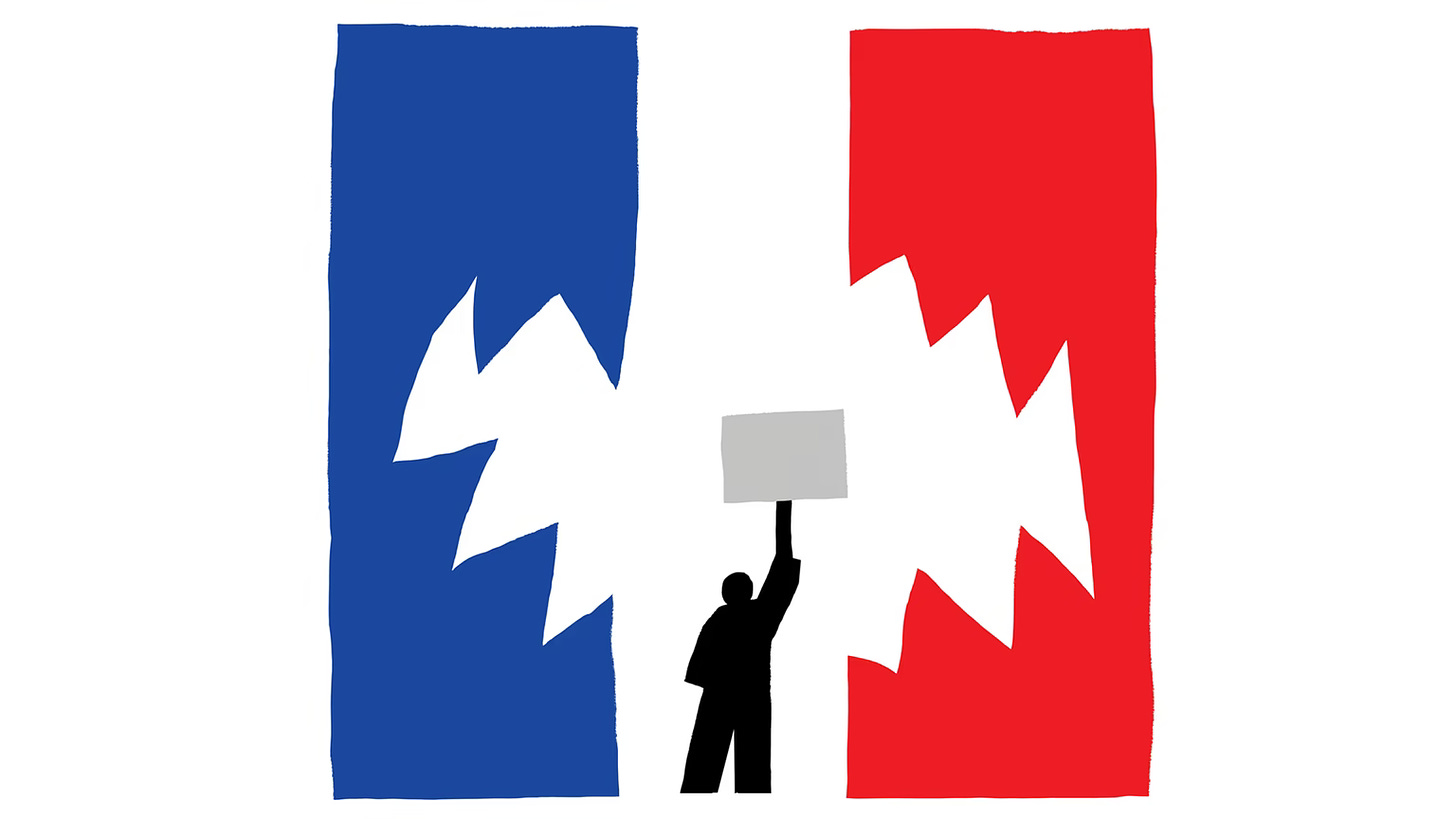

Thanks to America’s dominant global position, its influence is felt everywhere and in many different ways. One example is “wokeness”, which has found fertile ground in many parts of Europe. Two years ago, we took a look at how the French were reacting to woke culture, and how Macron “declared war” on it, insisting (rightfully) that it was at odds with “Liberté, égalité, fraternité”, the official motto of France. Wokeness, with its focus on identity, runs afoul of French Republicanism, one that is officially colour-blind, to the point where it is illegal to keep stats on race and faith.

Despite government and public opposition, wokeness continues to make inroads in France thanks to a young cohort of minorities influenced (and in some cases, taught and trained) by American political culture. Thomas Chatterton Williams, an American writer based in Paris, is a proponent of the “colour-blind society” as he views it as necessary to preserve multiculturalism. He takes a deep dive into France’s battle with “Le Wokisme” from his centrist liberal perspective in this long piece from The Atlantic:

Over the course of the conference, speakers had repeatedly debated whether what the French have termed le wokisme is a serious concern. A majority of the panelists and audience members, myself included, had answered more or less in the affirmative. Political organization around identity rather than ideology is one of the best predictors of civil strife and even civil war, according to an analysis of violent conflicts by the political scientist Barbara F. Walter. By pitting groups against one another in a zero-sum power struggle—and sorting them on a scale of virtue based on privilege and oppression—wokeness can’t help but elevate race and ethnicity to an extent that expands prejudice rather than reducing it, in the process fueling or, at minimum, providing cover for a violent and dangerous majoritarian reaction. That, at least, was the prevailing sense of the group.

Although it has made inroads into French politics, it is nowhere near the level of success that it has achieved in the USA and Canada.

As the last panel, “Media and Universities: In Need of Reform and Reassessment?,” got under way, Diallo took the opportunity to argue the opposite position. Onstage with her were a political scientist and two philosophy professors, one of whom was the moderator, Perrine Simon-Nahum. Diallo is a well-known and polarizing figure in France, a telegenic proponent of identity politics with a large social-media following. She draws parallels between the French and American criminal-justice systems (one of her documentaries is called From Paris to Ferguson), making the case that institutional racism afflicts her nation just as it does the U.S., most notably in discriminatory stop-and-frisk policing. Her views would hardly be considered extreme in America, but here she is seen in some quarters as a genuinely subversive agent.

Diallo IS a subversive agent, and can be considered an American one thanks to what Chatterton Williams shares with us later on in the article:

In 2010, the U.S. State Department invited French politicians and activists to a leadership program to help them strengthen the voice and representation of ethnic groups that have been excluded from government. Rokhaya Diallo attended, which many of her critics still use as evidence that she is a trained proselytizer of American social-justice propaganda. (In 2017, under pressure from both the left and the right, Macron’s government asked for her removal—as Diallo put it to me, it “canceled” her—from a government advisory council, seemingly on the grounds that race- and religious-based political organizing contradicts key principles of French republicanism and secularism, or laïcité.)

But in a classified memo published on WikiLeaks, former U.S. Ambassador Charles H. Rivkin laid out the pragmatic, self-interested rationale for the program, part of what was called a “Minority Engagement Strategy”:

French institutions have not proven themselves flexible enough to adjust to an increasingly heterodox demography. We believe that if France, over the long run, does not successfully increase opportunity and provide genuine political representation for its minority populations, France could become a weaker, more divided country, perhaps more crisis-prone and inward-looking, and consequently a less capable ally.

What do you call a person who goes to a foreign country to receive training from them in how to exacerbate divisions back at home? Anyway….

The woke “have discovered new epistemologies,” Jean-François Braunstein, a philosophy professor at Panthéon-Sorbonne University, nonetheless retorted—theories of knowledge that validate feelings over facts. He called Diallo’s position “a staunch attack against science and against truth.” He appeared to want to expand the conversation’s scope beyond racial identity to encompass the dissolution of the gender binary, which was not a subject Diallo had been addressing. Simon-Nahum demurred but suggested that the larger disagreement about “the conception of knowledge” was still worrying; it justified fears that the French discourse was becoming Americanized.

Diallo replied that most people in attendance were likely “privileged,” and as such, disproportionately fearful of the “emergence of minority speech [from] people who indeed didn’t have access to certain clubs … and are questioning things that were considered” unquestionable.

She sounds exactly like an American shitlib.

Chatterton Williams concedes her point, and then goes on to do what all liberals do; reveal their fear of the hard right coming to power via a reaction:

The French reaction to le wokisme has been revelatory for me. I am working on a book about the ways American culture and institutions changed after the summer of 2020, and how that transformation has, to an unusual degree, reverberated internationally, and particularly in France. The incident at the Tocqueville conference caused me to recalibrate some of my assumptions—and to appreciate more keenly just how easily anti-wokeness can succumb to a dogmatism as rigid as the one it seeks to oppose. Many of the debates here take place as if in a parallel universe, eerily familiar but with several illuminating differences. They are a useful prism for contemplating the excesses and limitations, as well as the merits, of the social-justice fervor that has gripped the United States.

This reaction was heightened by how American media treated the murder of a French schoolteacher by a Chechen migrant who adhered to a radical form of Islam:

For many in France, a headline in The New York Times crystallized this new attitude of reproach. Following the beheading of a middle-school teacher named Samuel Paty in October 2020—for the transgression of showing those Charlie Hebdo cartoons in the classroom—the American newspaper of record’s first encapsulation of the attack focused not on Paty but on his assailant: “French Police Shoot and Kill Man After a Fatal Knife Attack on the Street.” The headline was subsequently changed, and the article itself was relatively balanced. But when it described Paty as having “incited anger among some Muslim families,” the implication to many French readers was unambiguous: Teaching the universal value of free speech to all students, regardless of ethnic affiliation, was what had really led to Paty’s murder. French audiences took this idea—which was echoed throughout much of the American media—as an exoneration of Paty’s assassin, an 18-year-old Chechen asylum recipient with extremist beliefs who had hunted down his victim only after learning of his existence from a social-media mob.

Reading such coverage in the American press was painful for many French people of all ethnicities and religious affiliations. For months, the perceived abandonment by an admired and influential ally was the subject of constant conversation. Why were American commentators using Paty’s killing to score points on Twitter by condemning a society they did not know? Why had the Times framed this act of savagery as a simple—and, one might infer, possibly excessive—police shooting? Why were journalists at other outlets, including The Washington Post, reinforcing a narrative that reduced complex issues of secularism, republicanism, and immigration to broad allegations of Islamophobia? Why were critics on social media resorting to the blunt racial catchall of whiteness? Did they not understand that French citizens of African or Arab descent were also appalled by such violence?

Many French people began to see their nation as a pivotal theater of resistance to woke orthodoxy. Macron himself became a determined critic, insisting that his country follow its own path to achieve a multiethnic democracy, without mimicking the identity-obsessed American model. “We have left the intellectual debate to … Anglo-Saxon traditions based on a different history, which is not ours,” he argued just before Paty’s killing, in his October 2020 speech against “Islamist separatism.” Macron’s minister of national education at the time, Jean-Michel Blanquer, spoke of the need to wage “a battle” against the woke ideas being promulgated by American universities.

Wokeness is just one facet of the continuing Americanization of the European continent, so it is important that we continue to monitor how France tries to defend itself from it while allowing all other facets to capture it.

I first learned of Seymour (Sy) Hersh in the late 1990s when his book “The Dark Side of Camelot” detailing some then-unknown aspects of JFK’s life was published. I had no idea that he was already a very, very famous and well-respected investigative journalist at that time (for example, he broke the story of the My Lai Massacre in 1969, earning him a Pulitzer Prize a year later). A few years after the release of the JFK book, he went on break the Abu Ghraib story, winning him even more accolades. Hersh was THE titan of investigative journalism.

The increasing politicization of American journalism has not been kind to him. He made many enemies for disputing the Obama Administration’s claims regarding the assassination of Osama bin Laden, and made even more by questioning US-led assertions that Bashar Assad was using chemical weapons on civilians in Syria. The climate has gotten so bad for him that he can no longer get published in mainstream American media, leaving him no option but to become my colleague here at Substack (in less than a week he has already amassed an incredible 54,000 subscribers!!!!).

Unlike the bombshells that made his reputation in the past, Hersh has written a piece detailing the story behind the worst kept secret in the world: Russia did not bomb Nordstream 2. Hersh naturally points the finger at the USA as the prime culprit in this affair.

The U.S. Navy’s Diving and Salvage Center can be found in a location as obscure as its name—down what was once a country lane in rural Panama City, a now-booming resort city in the southwestern panhandle of Florida, 70 miles south of the Alabama border. The center’s complex is as nondescript as its location—a drab concrete post-World War II structure that has the look of a vocational high school on the west side of Chicago. A coin-operated laundromat and a dance school are across what is now a four-lane road.

The center has been training highly skilled deep-water divers for decades who, once assigned to American military units worldwide, are capable of technical diving to do the good—using C4 explosives to clear harbors and beaches of debris and unexploded ordinance—as well as the bad, like blowing up foreign oil rigs, fouling intake valves for undersea power plants, destroying locks on crucial shipping canals. The Panama City center, which boasts the second largest indoor pool in America, was the perfect place to recruit the best, and most taciturn, graduates of the diving school who successfully did last summer what they had been authorized to do 260 feet under the surface of the Baltic Sea.

Last June, the Navy divers, operating under the cover of a widely publicized mid-summer NATO exercise known as BALTOPS 22, planted the remotely triggered explosives that, three months later, destroyed three of the four Nord Stream pipelines, according to a source with direct knowledge of the operational planning.

Two of the pipelines, which were known collectively as Nord Stream 1, had been providing Germany and much of Western Europe with cheap Russian natural gas for more than a decade. A second pair of pipelines, called Nord Stream 2, had been built but were not yet operational. Now, with Russian troops massing on the Ukrainian border and the bloodiest war in Europe since 1945 looming, President Joseph Biden saw the pipelines as a vehicle for Vladimir Putin to weaponize natural gas for his political and territorial ambitions.

Hersh’s piece is courtesy of a single, anonymous source. This makes him very open to criticism and attacks, which is quite fair. What he has done is put the story front and centre (at least for now).

Biden’s decision to sabotage the pipelines came after more than nine months of highly secret back and forth debate inside Washington’s national security community about how to best achieve that goal. For much of that time, the issue was not whether to do the mission, but how to get it done with no overt clue as to who was responsible.

As I shared last week:

President Biden and his foreign policy team—National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, Secretary of State Tony Blinken, and Victoria Nuland, the Undersecretary of State for Policy—had been vocal and consistent in their hostility to the two pipelines, which ran side by side for 750 miles under the Baltic Sea from two different ports in northeastern Russia near the Estonian border, passing close to the Danish island of Bornholm before ending in northern Germany.

The direct route, which bypassed any need to transit Ukraine, had been a boon for the German economy, which enjoyed an abundance of cheap Russian natural gas—enough to run its factories and heat its homes while enabling German distributors to sell excess gas, at a profit, throughout Western Europe. Action that could be traced to the administration would violate US promises to minimize direct conflict with Russia. Secrecy was essential.

Germany now has to buy much more expensive gas to fuel its export-based economy, thus reducing its competitiveness on the global market. Oops!

This is an excellent summary of the geopolitical importance of these pipelines, for those not aware of it already:

From its earliest days, Nord Stream 1 was seen by Washington and its anti-Russian NATO partners as a threat to western dominance. The holding company behind it, Nord Stream AG, was incorporated in Switzerland in 2005 in partnership with Gazprom, a publicly traded Russian company producing enormous profits for shareholders which is dominated by oligarchs known to be in the thrall of Putin. Gazprom controlled 51 percent of the company, with four European energy firms—one in France, one in the Netherlands and two in Germany—sharing the remaining 49 percent of stock, and having the right to control downstream sales of the inexpensive natural gas to local distributors in Germany and Western Europe. Gazprom’s profits were shared with the Russian government, and state gas and oil revenues were estimated in some years to amount to as much as 45 percent of Russia’s annual budget.

America’s political fears were real: Putin would now have an additional and much-needed major source of income, and Germany and the rest of Western Europe would become addicted to low-cost natural gas supplied by Russia—while diminishing European reliance on America. In fact, that’s exactly what happened. Many Germans saw Nord Stream 1 as part of the deliverance of former Chancellor Willy Brandt’s famed Ostpolitik theory, which would enable postwar Germany to rehabilitate itself and other European nations destroyed in World War II by, among other initiatives, utilizing cheap Russian gas to fuel a prosperous Western European market and trading economy.

Nord Stream 1 was dangerous enough, in the view of NATO and Washington, but Nord Stream 2, whose construction was completed in September of 2021, would, if approved by German regulators, double the amount of cheap gas that would be available to Germany and Western Europe. The second pipeline also would provide enough gas for more than 50 percent of Germany’s annual consumption. Tensions were constantly escalating between Russia and NATO, backed by the aggressive foreign policy of the Biden Administration.

Opposition to Nord Stream 2 flared on the eve of the Biden inauguration in January 2021, when Senate Republicans, led by Ted Cruz of Texas, repeatedly raised the political threat of cheap Russian natural gas during the confirmation hearing of Blinken as Secretary of State. By then a unified Senate had successfully passed a law that, as Cruz told Blinken, “halted [the pipeline] in its tracks.” There would be enormous political and economic pressure from the German government, then headed by Angela Merkel, to get the second pipeline online.

The key point is: “…diminishing European reliance on America.”

What became clear to participants, according to the source with direct knowledge of the process, is that Sullivan intended for the group to come up with a plan for the destruction of the two Nord Stream pipelines—and that he was delivering on the desires of the President.

Over the next several meetings, the participants debated options for an attack. The Navy proposed using a newly commissioned submarine to assault the pipeline directly. The Air Force discussed dropping bombs with delayed fuses that could be set off remotely. The CIA argued that whatever was done, it would have to be covert. Everyone involved understood the stakes. “This is not kiddie stuff,” the source said. If the attack were traceable to the United States, “It’s an act of war.”

At the time, the CIA was directed by William Burns, a mild-mannered former ambassador to Russia who had served as deputy secretary of state in the Obama Administration. Burns quickly authorized an Agency working group whose ad hoc members included—by chance—someone who was familiar with the capabilities of the Navy’s deep-sea divers in Panama City. Over the next few weeks, members of the CIA’s working group began to craft a plan for a covert operation that would use deep-sea divers to trigger an explosion along the pipeline.

More threats:

What came next was stunning. On February 7, less than three weeks before the seemingly inevitable Russian invasion of Ukraine, Biden met in his White House office with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who, after some wobbling, was now firmly on the American team. At the press briefing that followed, Biden defiantly said, “If Russia invades . . . there will be no longer a Nord Stream 2. We will bring an end to it.”

Twenty days earlier, Undersecretary Nuland had delivered essentially the same message at a State Department briefing, with little press coverage. “I want to be very clear to you today,” she said in response to a question. “If Russia invades Ukraine, one way or another Nord Stream 2 will not move forward.”

Germany’s ally (or allies) blew up the pipelines in order that it would have to turn to them to buy gas, at a much, much higher price. These are not allies, these are racketeers.

The greatest conspiracy of the 21st century has been how mainstream media colluded with government officials to promote the idea that Trump worked with Russia in the run up to the 2016 US Presidential Election.

The conspiracy was a success, as Trump was driven from office four years later.

The fact that the conspiracy relied on bullshit is a minor matter, because the conspirators got away with it. Simple as. The collapse in trust in mainstream media is an acceptable price to pay for the conspirators, because their positions remain secure, and accountability for their actions is nowhere on the horizon. It’s great to learn the truth about how they conspired, but the damage has already been done.

Jeff Gerth takes the media to task for its malicious behaviour and consistent failures of professionalism in this long piece for the Columbia Journalism Review.

The end of the long inquiry into whether Donald Trump was colluding with Russia came in July 2019, when Robert Mueller III, the special counsel, took seven, sometimes painful, hours to essentially say no.

“Holy shit, Bob Mueller is not going to do it,” is how Dean Baquet, then the executive editor of the New York Times, described the moment his paper’s readers realized Mueller was not going to pursue Trump’s ouster.

Baquet, speaking to his colleagues in a town hall meeting soon after the testimony concluded, acknowledged the Times had been caught “a little tiny bit flat-footed” by the outcome of Mueller’s investigation.

That would prove to be more than an understatement. But neither Baquet nor his successor, nor any of the paper’s reporters, would offer anything like a postmortem of the paper’s Trump-Russia saga, unlike the examination the Times did of its coverage before the Iraq War.

In fact, Baquet added, “I think we covered that story better than anyone else” and had the prizes to prove it, according to a tape of the event published by Slate. In a statement to CJR, the Times continued to stand by its reporting, noting not only the prizes it had won but substantiation of the paper’s reporting by various investigations. The paper “thoroughly pursued credible claims, fact-checked, edited, and ultimately produced ground-breaking journalism that has proven true time and again,” the statement said.

But outside of the Times’ own bubble, the damage to the credibility of the Times and its peers persists, three years on, and is likely to take on new energy as the nation faces yet another election season animated by antagonism toward the press. At its root was an undeclared war between an entrenched media, and a new kind of disruptive presidency, with its own hyperbolic version of the truth.

Given awards and accolades, and facing no reckoning for what it had done, the NY Times has all the incentive to repeat its actions during the Trump Administration.

But news outlets and watchdogs haven’t been as forthright in examining their own Trump-Russia coverage, which includes serious flaws. Bob Woodward, of the Post, told me that news coverage of the Russia inquiry ” wasn’t handled well” and that he thought viewers and readers had been “cheated.” He urged newsrooms to “walk down the painful road of introspection.”

They have no incentive to do so.

By 2016, as Trump’s political viability grew and he voiced admiration for Russia’s “strong leader,” Clinton and her campaign would secretly sponsor and publicly promote an unsubstantiated conspiracy theory that there was a secret alliance between Trump and Russia. The media would eventually play a role in all that, but at the outset, reporters viewed Trump and his candidacy as a sideshow. Maggie Haberman of the Times, a longtime Trump chronicler, burst into a boisterous laugh when a fellow panelist on a television news show suggested Trump might succeed at the polls.

The bolded portion was easily deduced at the time, but for years anyone saying it would be denounced as a “Russian agent” among other things.

Those concerns would be supercharged by a small group of former journalists turned private investigators who operated out of a small office near Dupont Circle in Washington under the name Fusion GPS.

In late May 2016, Glenn Simpson, a former Wall Street Journal reporter and a Fusion cofounder, flew to London to meet Steele, a former official within MI6, the British spy agency. Steele had his own investigative firm, Orbis Business Intelligence. By then, Fusion had assembled records on Trump’s business dealings and associates, some with Russia ties, from a previous, now terminated engagement. The client for the old job was the Washington Free Beacon, a conservative online publication backed in part by Paul Singer, a hedge fund billionaire and a Republican Trump critic. Weeks before the trip to London, Fusion signed a new research contract with the law firm representing the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign.

Simpson not only had a new client, but Fusion’s mission had changed, from collection of public records to human intelligence gathering related to Russia. Over lasagna at an Italian restaurant at Heathrow Airport, Simpson told Steele about the project, indicating only that his client was a law firm, according to a book co-authored by Simpson. The other author of the 2019 book, Crime in Progress, was Peter Fritsch, also a former WSJ reporter and Fusion’s other cofounder. Soon after the London meeting, Steele agreed to probe Trump’s activities in Russia. Simpson and I exchanged emails over the course of several months. But he ultimately declined to respond to my last message, which had included extensive background and questions about Fusion’s actions.

and

Soon, a purported Romanian hacker, Guccifer 2.0, published DNC data, starting with the party’s negative research on Trump, followed by the DNC dossier on its own candidate, Clinton.

The next week, the Post weighed in with a long piece, headlined “Inside Trump’s Financial Ties to Russia and His Unusual Flattery of Vladimir Putin.” It began with Trump’s trip to Moscow in 2013 for his Miss Universe pageant, quickly summarized Trump’s desire for a “new partnership” with Russia, coupled with a possible overhaul of NATO, and delved into a collection of Trump advisers with financial ties to Russia. The piece covered the dependence of Trump’s global real estate empire on wealthy Russians, as well as the “multiple” times Trump himself had tried and failed to do a real estate deal in Moscow.

The lead author of the story, Tom Hamburger, was a former Wall Street Journal reporter who had worked with Simpson; the two were friends, according to Simpson’s book. By 2022, emails between the two from the summer of 2016 surfaced in court records, showing their frequent interactions on Trump-related matters. Hamburger, who recently retired from the Post, declined to comment. The Post also declined to comment on Hamburger’s ties to Fusion.

A gaggle of media shitheads pounced:

On July 18, the first day of the gathering, Josh Rogin, an opinion columnist for the Washington Post, wrote a piece about the party’s platform position on Ukraine under the headline “Trump campaign guts GOP’s anti-Russian stance on Ukraine.” The story would turn out to be an overreach. Subsequent investigations found that the original draft of the platform was actually strengthened by adding language on tightening sanctions on Russia for Ukraine-related actions, if warranted, and calling for “additional assistance” for Ukraine. What was rejected was a proposal to supply arms to Ukraine, something the Obama administration hadn’t done.

Rogin’s piece nevertheless caught the attention of other journalists. Within a few days, Paul Krugman, in his Times column, called Trump the “Siberian candidate,” citing the “watering down” of the platform. Jeffrey Goldberg, the editor of The Atlantic, labeled Trump a “de facto agent” of Putin.

The nasty climate that ensued:

Matt Taibbi, who spent time as a journalist in Russia, also grew uneasy about the Trump-Russia coverage. Eventually, he would compare the media’s performance to its failures during the run-up to the Iraq War. “It was a career-changing moment for me,” he said in an interview. The “more neutral approach” to reporting “went completely out the window once Trump got elected. Saying anything publicly about the story that did not align with the narrative—the repercussions were huge for any of us that did not go there. That is crazy.”

This piece is full of details, too many to go into for now, so please read the rest here.

Elites on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean are confident in the idea that populism has either hit a wall or is receding like a tide. This means that they can get back to business as usual, and one big item on the list is opening the doors of their countries to migrants so as to gain access to cheap labour.

Ireland is no exception to this, but something interesting is happening there; anti-migrant protests are increasing in volume and strength across the country, as Peter Ryan reports:

Ireland has an immigration problem. Almost a year after refugees started to arrive from Ukraine, leaving state capacity buckled and local communities unnerved, two very different expressions of civic disorder have emerged. In one, migrants are housed in cubicle dorms in office buildings or, even worse, in tents. In the other, grassroots anti-migrant protests are sweeping across the country, rallying around the slogan “Ireland is Full”. There were 307 anti-migrant protests in 2022, while 2023 has already seen 64. At the latest demonstration in Dublin, on Tuesday, more than 2,000 protestors took to the streets.

The focal point of the protests is Dublin’s East Wall, where, in November, after the government converted a state building into a migrant residence without consulting locals, hundreds of people started to gather week after week. By December, the demonstrations spread to other areas — Drimnagh, Finglas, Ballymun and Fermoy. Rather than losing steam as each month went by, the protests continued to intensify, sprouting across the country. And as they did, it became clear that they were different from other anti-migrant demonstrations in Europe.

Different how?

The demographic profile of each faction revealed something curious. As one might expect, the anti-migrant protesters were from the working-class areas where the migrants are being housed, while the counter-protesters were largely middle-class liberals. More surprising, however, was the significant proportion of women among the anti-migrant contingent.

One of the principal motivating factors behind Ireland’s anti-migrant protests concerns a number of reports of migrants mistreating women and even young children. Last week, for instance, a male migrant allegedly walked into Temple Street Children’s Hospital and announced that he wanted to rape children. This week, a migrant was charged by the Gardai with the sexual assault of a teenage girl.

Polling:

The impact of such incidents is borne out in national polls: in one recent survey carried out by The Business Post, only 38% of women supported building new homes for migrants, compared to 55% of men. As The Irish Independent noted: “The view that Ireland has taken in too many refugees is notably stronger among women in working-class communities.”

Ireland’s political topology:

In any other European country, such a scenario would be ripe for a Right-wing populist party to make electoral headway. But Ireland’s modern political landscape has no equivalent to Le Pen, Orbán, or Trump. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have ruled Ireland for a century. The former positions itself as more traditional and working-class, and the latter as more secular and pro-business — but, by and large, they govern identically. Over the past decade, as any legacy of Right-wing attitudes dissipated from the post-Celtic Tiger Ireland, anti-establishment angst had channelled itself into support for the rising Sinn Féin party — to great success. Under the slogan promising “time for change”, the party’s first-place position suggests it will take control of the government in the next election. Unless, that is, the anti-migrant protests overshadow Sinn Féin’s rising star.

These working-class protesters are the same demographic as Sinn Féin’s reliable voter base. As Dublin City University Professor Eoin O’Malley discovered after polling individual issues, “Sinn Féin support is correlated with anti-immigrant sentiment”.

Sinn Fein voters might not seem fond of the migrants, but their leadership is rather different:

This anti-immigrant sentiment contrasts starkly with the Sinn Féin party leadership, which perhaps explains the three-point drop from its all-time high last June. It is noticeable, for instance, that the East Wall protests were actually located in Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou McDonald’s constituency. A number of placards showed a photo of McDonald with the words “Traitor” written across it. Similarly, protests in Finglas singled out the local Sinn Féin TD Dessie Ellis for condemnation.

Amid such a politically hostile climate, Sinn Féin’s detachment from its anti-migrant working-class base is starting to open the door to something modern Ireland has never experienced: Right-wing populist parties, the most prominent being the Irish Freedom Party (IFP).

Ryan goes on to explain that the IFP is merely a blip on the Irish political radar at present, but Sinn Fein has now given it an opening to exploit.

We end this weekend’s Substack with an interesting piece by Nemets on the subject of how some people in the African country of Chad have a paternal genetic lineage that is out of place on that continent, but is very present in Europe.

Many men among both the Laal, the Hausa, and other Chadic speaking peoples carry the Y chromosomal haplogroup R1b-V88. It puzzled scientists for a number of years as R1b lineages are most common in Europe, and there was no obvious connection between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. The puzzlement increased with the discovery of bodies with specifically R1b-V88 lineages in 8th millennium BC Ukraine and 9th or 10th millennium BC Serbia. The R1b-V88 lineage most common within Africa shows a “star shaped phylogeny” that dates to the early 4th millennium BC - that is, the men carrying it at the time were the direct forefathers of many, likely as the result of violent conquests and polygyny. While entire story of Hausa and Laal origins will likely never be known, we do know enough about prehistory to see at least the outlines of the journey of their forefathers.

The world was very different in 7000 BC, not just in technology and human population, but also in geography and ecology. Britain was connected to Europe by a land bridge across the North Sea. The Sahara Desert was mostly a savanna, inhabited by fishermen, foragers, and hunters. The Nile had a third tributary river that flowed from west in what is now eastern Chad to the east in the Dongola Bend.

In Europe, farmers from Anatolia (what is now the Asian part of Turkey) were just beginning to settle Greece and the Balkans. Various hunter-gatherer tribes, some quite distinctive, reigned across the rest of the Europe. In Africa, the northwest was inhabited by a population with affinities to both contemporary Levantines and certain unsampled and non-extant populations in the Sahara - the Iberomaurusians. The Khoe, famous for the clicks in their languages, had not arrived in South Africa. The highlands of Ethiopia were the hunting grounds of a race of short men (though still tall enough to not be dwarves). What we think of as the black race, if it existed at the time, had yet to cross the Mambilla Escarpment in what is now Cameroon and Nigeria east and south.

Beyond the Mambilla Escarpment there were a multitude of races, differing from each to varying degrees, with some quite distinctive. Humanity’s cousin species such as the Denisovans and Neanderthals were long extinct in Eurasia and Melanesia, but it is possible that some had endured past the end of the Ice Age in parts of Africa. Even today, in the highlands of Cameroon, some men still bear lineages that diverged from that of all other men over 200,000 years ago - perhaps a legacy of one of those cousins.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

For paid subscribers, we are now testing out the chat feature on both Apple and Android phones. If you want to participate, read here.

Hit the like button above to like this entry and use the share button to share this across social media.

Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so (be nice!), and please consider subscribing if you haven't done so already. We are now testing out the chat feature on both Apple and Android phones. Learn more here - https://niccolo.substack.com/p/fisted-by-foucault-subscriber-chat

I will turn back to the book club tomorrow, and post a few more entries over the course of next week thanks to having a bit more time to devote to my writing.

RE: Wokisme, if you have a good grasp of French then there’s an excellent philosophy podcast called “Le Précepteur” that did a pretty solid episode on Le Wokisme—I think it gives a good insight into the way it’s perceived by French intellectuals; or at least, the ones who aren’t totally Atlanticized.

RE: Russiagate—something I’ve seen firsthand is how much normie progressives still believe in the whole thing and believe the conspiracy was vindicated by Mueller and co. It’s a complete motte and bailey argument; the now well established fact that some campaign officials like Manafort did in fact have contact with Russians is treated as proof that Russiagate was fundamentally correct, as if those contacts were what the whole conspiracy theory was about the whole time when in reality it was a cluster of wildly unhinged speculation about Trump working directly for Putin. It’s honestly embarrassing now thoroughly the Donald broke these people’s brains.