Saturday Commentary and Review #111

Germany the American Satrapy, RAND Urges US Pull Plug on Ukraine War, Serbia Snookered by the West, Remote Work as City Killer, Haitian Voudou in the Diaspora

Leftist German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck is a favourite of this Substack for his realistic, no-holds barred criticism of today’s prevailing western liberal mores and politics, and above all else, its predatory, nation-killing capitalism (he has attacked open borders quite a bit!).1

It is a testament to the shifting sands of politics that some right wingers have to reach out to certain quarters of the left in order to gain a broader perspective as to what is happening in places like Germany, where according to Streeck:

“Bizarre things are happening, with public consideration of them tightly managed by an alliance of the centrist parties and the media, and supported to an amazing extent by self-imposed censorship in civil society.”

“Tightly managed” is a great way to describe not just Burnham’s Managerial Society, but specifically the debate around the EU’s (and more specifically, Germany’s) role in the war in Ukraine. It is this lack of debate stemming from the voluntary self-censorship of German media and civil society that is the subject of Streeck’s piece (here is the link again) that was first published in November of last year. Germany has not only sacrificed its economic competitiveness to satiate US foreign policy goals, but is also now willingly chipping away at its own physical security by going along with the step-by-step escalations driven by the Americans that threaten nuclear war, where Germany is itself on the actual front line.

On 17 October, Bundeskanzler Olaf Scholz invoked his constitutional privilege under Article 65 of the Grundgesetz to ‘determine the guidelines’ of his government’s policy. Chancellors do this rarely, if at all; the political wisdom is three strikes and you’re out. At stake was the lifespan of Germany’s last three nuclear power plants. As a result of Merkel’s post-Fukushima turn, intended to pull the Greens into a coalition with her party, these are scheduled by law to go out of service by the end of 2022. Afraid of nuclear accidents and nuclear waste, and also of their well-to-do middle-class voters, the Greens, now governing together with SPD and FDP, refused to give up their trophy. The FDP, on the other hand, demanded that given the current energy crisis, all three plants – accounting for about six percent of the domestic German electricity supply – be kept in operation as long as needed, meaning indefinitely. To end the fighting, Scholz issued an order to the ministries involved, formally declaring it government policy that the plants continue until mid-April next year, par ordre du mufti, as German political jargon puts it. Both parties knuckled under, saving the coalition for the time being.

The Greens – recently called ‘the most hypocritical, aloof, mendacious, incompetent and, measured by the damage they cause, the most dangerous party we currently have in the Bundestag’ by the indestructible Sahra Wagenknecht – are rather more afraid of nuclear power than nuclear arms. Anesthetized by the rapidly rising number of Green fellow-travellers in the media and mesmerized by fantasies of Biden delivering Putin to The Hague to stand trial in the international criminal court, the German public refuses to consider the damage nuclear escalation in Ukraine would cause, and what it would mean for the future of Europa and, for that matter, Germany (a place many German Greens do not consider particularly worth protecting anyway). With few exceptions, German political elites, as well as their agitprop mainstream press, know or pretend to know nothing about either the current state of nuclear arms technology or the role assigned to the German military in the nuclear strategy and tactics of the United States.

It’s tough to summarize Streeck’s words since he does such an excellent job in depicting the situation through his writing style. The German Greens apparently do fear nuclear power more than nuclear arms. Their actions make this conclusion inescapable.

Willing subservience and brazen stupidity:

Before one’s eyes, an apparently democratically governed mid-sized regional power is being turned, and is actively turning itself, into a transatlantic dependency of the Great American War Machines, from NATO to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Pentagon to the NSA, and the CIA to the National Security Council. When on 26 September the two Nord Stream pipelines were hit by a massive underwater attack, the powers that be tried for a few days to convince the German public that the perpetrator could only have been ‘Putin’, intending to demonstrate to the Germans that there would be no return to the good old gas days. It soon became clear, however, that this strained the credulity of even the most credulous of German Untertanen. Why should what is called ‘Putin’ have voluntarily deprived himself of the possibility, small as it might be, of luring Germany back into energy dependency, as soon as the Germans became unable to pay the staggering price of American Liquid Natural Gas? And why would he not have blown up the pipelines in Russian rather than international waters, the latter more heavily policed than any other maritime landscape except, perhaps, the Persian Gulf? Why risk a squadron of Russian shock troops, which would undoubtedly have been sizeable, being caught red-handed, triggering a direct confrontation with several NATO member states under Article 5?

That charade officially ended a little over a week ago when Russia/Ukraine policy chief Vicki Nuland cheered on the destruction of NS 2 during a Senate hearing:

Now check this out:

There have been further ominous events of this kind. In an accelerated procedure lasting only two days, the Bundestag, using language supplied by the Ministry of Justice held by the supposedly liberal FDP, amended Section 130 of the Criminal Code, which makes it a crime to ‘approve, deny or diminish (verharmlosen)’ the Holocaust. On 20 October, an hour before midnight, a new paragraph was passed, hidden in an omnibus bill dealing with the technicalities of creating central registers, which adds ‘war crimes’ (Kriegsverbrechen) to what must not be approved, denied or diminished. The coalition and the CDU/CSU voted for the amendment, Die Linke and AfD against. There was no public debate. According to the government, the amendment was needed for the transposition into German law of a European Union directive to fight racism. With two minor exceptions, the press failed to report on what is nothing other than a legal coup d’état. (Two weeks later the FAZ protested that using Section 130 for the purpose was disrespectful of the unique nature of the Holocaust.)

It may not be long before the Federal Prosecutor starts legal proceedings against someone for comparing Russian war crimes in Ukraine to American war crimes in Iraq, thereby ‘diminishing’ the former (or the latter?). Similarly, the Federal Bureau for the Protection of the Constitution may soon begin to place ‘diminishers’ of ‘war crimes’ under observation, including surveillance of their telephone and email communication. Even more important for a country where almost everybody on the morning after the Machtübernahme greeted their neighbour with Heil Hitler rather than Guten Tag, will be what in the United States is called a ‘chilling effect’. Which journalist or academic having to feed a family or wishing to advance their career will risk being ‘observed’ by inland security as a potential ‘diminisher’ of Russian war crimes?

A very neat trick to stifle dissent!

In other respects as well, the corridor of the sayable is rapidly, and frighteningly, narrowing. As with the destruction of the pipelines, the strongest taboos relate to the role of the United States, both in the history of the conflict and in the present. In admissible public speech, the Ukrainian war – which is expected to be termed ‘Putin’s war of aggression’ (Angriffskrieg) by all loyal citizens – becomes entirely de-contextualized: it has no history outside of the ‘narrative’ of a decade-long brooding of a mad dictator in the Kremlin over how to best wipe out the Ukrainian people, facilitated by the stupidity, combined with greed, of the Germans falling for his cheap gas. As this writer found out when an interview he had given to the online edition of a centre-right German weekly, Cicero, was cut without consultation, among what is not to be mentioned in polite German society are the American rejection of Gorbachev’s ‘Common European Home’, the subversion within the United States of Clinton’s project of a ‘Partnership for Peace’, and the rebuff as late as 2010 of Putin’s proposal of a European free trade zone ‘from Lisbon to Vladivostok’. Equally unmentionable is the fact that by the mid-1990s at the latest, the United States had decided that the border of post-communist Europe should be identical to the western border of post-communist Russia, which would also be the eastern border of NATO, to the west of which there were to be no restrictions whatsoever on the stationing of troops and weapons systems. The same holds for the extensive American strategic debates on ‘extending Russia’, as documented in publicly accessible working papers of the RAND Corporation.

There is a greater range of debate available in the USA than there is in Germany regarding Russia, and especially the war in Ukraine.

The current climate:

In the Germany of today, any attempt to place the Ukrainian war in the context of the reorganization of the global state system after the end of the Soviet Union and the American project of a ‘New World Order’ (the elder Bush) is suspicious. Those who do run the risk of being branded as Putinversteher and invited on one of the daily talk shows on public television – for ‘false balance’ in the eyes of the militants – to face an armada of right-thinking neo-warriors shouting at them. Early in the war, on 28 April, Jürgen Habermas, court philosopher of the Greens, published a long article in Süddeutsche Zeitung, under the long title ‘Shrill tone, moral blackmail: On the battle of opinions between former pacifists, a shocked public and a cautious Chancellor following the attack on Ukraine’. In it, he took issue with the exalted moralism of the neo-bellicists among his followers, cautiously expressing support for what at the time appeared to be reluctance on the part of the Bundeskanzler for headlong involvement in the Ukrainian war. For this Habermas was fervently attacked from within what he must have thought was his camp, and has remained silent since.

A new generation of leftists have taken to Americanism and its militancy:

Some of the most warlike used to belong to the left, widely defined; today they are more or less aligned with the Green party and in this emblematically represented by Baerbock, now the foreign minister. A strange combination of Joan of Arc and Hillary Clinton, Baerbock is one of the many so-called ‘young global leaders’ cultivated by the World Economic Forum. What is most characteristic of her version of leftism is its affinity to the United States, by far the most violence-prone state in the contemporary world. To understand this, it may help to remember that those of her generation have never experienced war, and neither have their parents; indeed, it is safe to assume that its male members avoided the draft as conscientious objectors until it was suspended, not least under their electoral pressure. Moreover, no previous generation has grown up as much under the influence of American soft power, from pop music to movies and fashion to a succession of social movements and cultural fads, all of which were promptly and eagerly copied in Germany, filling the gap caused by the absence of any original cultural contribution from this remarkably epigonal age cohort (an absence that is euphemistically called cosmopolitanism).

Looking deeper, as one must, cultural Americanism, including its idealistic expansionism, promises a libertarian individualism which in Europe, unlike the United States, is felt to be incompatible with nationalism, the latter happening to be the anathema of the Green left. This leaves as the only remaining possibility for collective identification a generalized ‘Westernism’ misunderstood as a ‘values’-based universalism, which is in fact a scaled-up Americanism immune to contamination by the reality of American society. Westernism, abstracted from the particular needs, interests and commitments of everyday life, is inevitably moralistic; it can live only in Feindschaft with differently moral, and in its eyes therefore immoral, non-Westernism, which it cannot let live and ultimately must let die. Not least, by adopting Westernism, this kind of new left can for once hope to be not just on the right but also on the winning side, American military power promising them that this time, finally, they may not be fighting for a lost cause.

This is voluntary submission.

The RAND Corporation has been a leading US Military and foreign policy think tank since its founding in 1948. When it speaks, people listen. This is why it rather important to highlight it’s call for US foreign policy planners to not get bogged down in a protracted war in Ukraine, so as to not lose sight of the perceived challenge in East Asia by a rising China.

This is the first significant public stance by a leading American think tank that does not join the chorus demanding continued escalation in the war in Ukraine, leading some to conclude that the debate behind closed doors is getting louder, with some ready to declare ‘victory’ and move on to the next theatre.

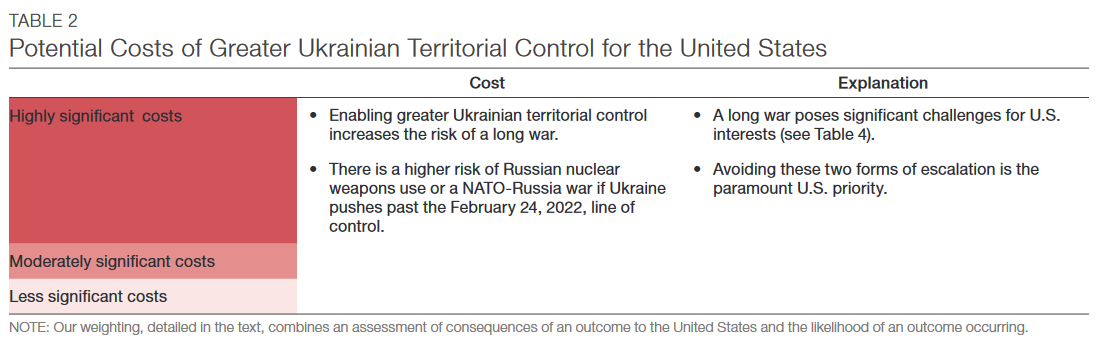

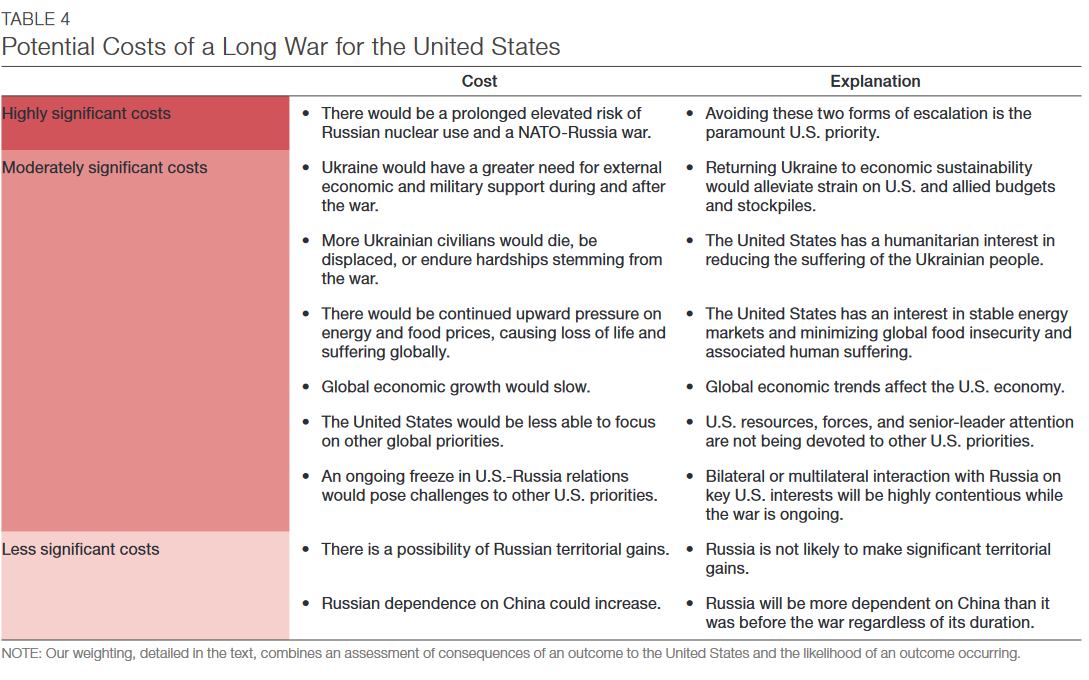

The authors argue that, in addition to minimizing the risks of major escalation, U.S. interests would be best served by avoiding a protracted conflict. The costs and risks of a long war in Ukraine are significant and outweigh the possible benefits of such a trajectory for the United States. Although Washington cannot by itself determine the war's duration, it can take steps that make an eventual negotiated end to the conflict more likely. Drawing on the literature on war termination, the authors identify key impediments to Russia-Ukraine talks, such as mutual optimism about the future of the war and mutual pessimism about the implications of peace. The Perspective highlights four policy instruments the United States could use to mitigate these impediments: clarifying plans for future support to Ukraine, making commitments to Ukraine's security, issuing assurances regarding the country's neutrality, and setting conditions for sanctions relief for Russia.

Please make a note of these four outlined policy instruments:

clarifying plans for future support to Ukraine

making commitments to Ukraine’s security

issuing assurances regarding the country’s neutrality

setting conditions for sanctions relief for Russia

Number 3 in particular is key, as that would satisfy Russia’s main concern: NATO expansion to Ukraine i.e. the big red line for Moscow.

Criticism of the neo-con faction:

Some analysts make the case that the war is heading toward an outcome that would benefit the United States and Ukraine. Ukraine had battlefield momentum as of

December 2022 and could conceivably fight until it succeeds in pushing the Russian military out of the country. Proponents of this view argue that the risks of Russian nuclear use or a war with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) will remain manageable.1 Once it is forced out of Ukraine, a chastened Russia would have little choice but to leave its neighbor in peace—and even pay

reparations for the damage it caused. However, studies of past conflicts and a close look at the course of this one suggest that this optimistic scenario is improbable.

Key:

An important caveat: This Perspective focuses on U.S. interests, which often align with but are not synonymous with Ukrainian interests. We acknowledge that Ukrainians have been the ones fighting and dying to protect their country against an unprovoked, illegal, and morally repugnant Russian invasion. Their cities have been flattened; their economy has been decimated; they have been the victims of the Russian army’s war crimes. However, the U.S. government nevertheless has an obligation to its citizens to determine how different war trajectories would affect U.S. interests and explore options for influencing the course of the war to promote those interests.

As I and others have been saying from the beginning of this war: US and Ukrainian interests are not totally aligned, and US interests trump Ukrainian ones. It is the Americans who can shut the switch at any time, leaving Kiev in the lurch, devastated economy, massive ruination and death, and a truncated state in its possession. The Americans achieved their main objective on the first day of the war; the detachment of Russia from Europe economically and politically. Everything since has been gravy. It is unfortunate that Ukrainians have failed to grasp this fact.

Calculations regarding American interests:

Note the conclusions:

The debate in Washington and other Western capitals over the future of the Russia-Ukraine war privileges the issue of territorial control. Hawkish voices argue for using increased military assistance to facilitate the Ukrainian military’s reconquest of the entirety of the country’s territory.71 Their opponents urge the United States to adopt the pre-February 2022 line of control as the objective, citing the escalation risks of pushing further.72 Secretary of State Antony Blinken has stated that the goal of U.S. policy is to enable Ukraine “to take back territory that’s been seized

from it since February 24.”73Our analysis suggests that this debate is too narrowly focused on one dimension of the war’s trajectory. Territorial control, although immensely important to Ukraine, is not the most important dimension of the war’s future for the United States. We conclude that, in addition to averting possible escalation to a Russia-NATO war or Russian nuclear use, avoiding a long war is also a higher priority for the United States than facilitating significantly more Ukrainian territorial control. Furthermore, the U.S. ability to micromanage where the line is ultimately drawn is highly constrained since the U.S. military is not directly involved in the fighting. Enabling Ukraine’s territorial control is also far from the only instrument available to the United States to affect the trajectory of the war. We have highlighted several other tools—potentially more potent ones—that Washington can use to steer the war toward a trajectory that better promotes U.S. interests. Whereas the United States cannot determine the territorial outcome of the war directly, it will have direct control over these policies.

A mismatch in objectives seriously harms Ukrainian aims as it pays the price in territory and blood. Kiev has to bank on the neo-conservative faction winning the debate in the corridors of power in the USA, and even then victory is far from guaranteed.

A dramatic, overnight shift in U.S. policy is politically impossible—both domestically and with allies—and would be unwise in any case. But developing these instruments now and socializing them with Ukraine and with U.S.

allies might help catalyze the eventual start of a process that could bring this war to a negotiated end in a time frame that would serve U.S. interests. The alternative is a long war that poses major challenges for the United States, Ukraine, and the rest of the world.

RAND acknowledges that it would still take some time for its position to become policy, if it actually does win out.

It’s not easy being Serbia these days.

Hemmed in on all sides by NATO and economically reliant on trade with the EU, this pro-Russian country finds itself at odds with most of its neighbours. To make matters even worse, it is now being pressured to make peace with its breakaway province of Kosovo, the overwhelmingly Albanian-populated heartland of Medieval Serbia.

Believe it or not, but the Serbs had a medieval empire in the 14th century, thanks to a period of aggressive expansionism aided by a weakened Byzantine Empire that was fighting for its life against the encroaching Ottomans. In 1389, the Serbs (aided by a coalition from Christendom) fought the invading Turks to a standstill at the Battle of Kosovo, but it was a battle from which the Serbs could not recover, leading to the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into the Western Balkans. Serbian independence was extinguished over the coming decades.

To trot out a tired cliche, Serbia rose like a phoenix from the ashes in the 19th century to find itself in the company of European nations, in large part thanks to the increasing weakness of its Ottoman overlords. The Serbs then went on a remarkable run of victories in war, expanding its Principality into a Kingdom. By 1919, the Serbian Army made it as far as the Austrian Alps and down into Albanian Shkoder, touching Greek Macedonia as well, as its King Petar I became the ruler of the new entity known as ‘The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes”, latter renamed “Yugoslavia”.

The unitarist constitution adopted by Yugoslavia in 1921 was the pinnacle of Serbian power post-Medieval Serbia. It was all downhill from there as it suffered immensely during the Second World War, leaving the victorious communist Partizans in power in Belgrade. Communist Yugoslavia saw to it that the Serbs’ influence be cut down to size. The wars that ended Yugoslavia were the result of border disputes in the cases of Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina (in which the Serbs claimed the right to secession based on the ethnic principle), and territorial integrity regarding the Serbian province of Kosovo-Metohija.

By 2008 Serbia had been cut down to size, with few friends left in its corner. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the USA and its allies want to clean up the Balkans and rid it of any lingering Russian influence. Part of this process involves the settlement of the Kosovo Question, and the West has many sticks at its disposal to force through a final resolution.

Branko Milanovic is a globally-respected economist and as far from a Serbian nationalist that a Serbian could possibly be. He is a Yugoslav at heart (a believer in the “brotherhood and unity” of South Slavs), but he too realizes that the West is very capable of playing dirty regarding his country. He asks: “Can Serbia survive the EU’s economic ultimatum?”.

Speculation as to the sticks are easy to make because there is a history of them:

Everybody of normal intelligence would say, “You have nothing to sell and we do not want to buy the brick”. But the EU then begins to list the ultimatums. We do not know the text of the ultimatum, but it does not take great imagination to realize that threats must range from the suspension of EU negotiations, elimination of EU support funds (that Serbia gets as a candidate member), reintroduction of visas, discouragement of EU investors, to possibly additional financial sanctions (say, no access to short-term commercial loans), ban on long-term lending by the European banks, EBRD and possibly the World Bank and the IMF, and for the very end elements of a true embargo and perhaps seizure of assets. Serbia does not have oligarchs but it does have National Bank reserves and many companies that keep money in foreign banks in order to finance trade.

Branko paints a grim picture:

The question then becomes: can the country survive such sanctions that may last from five to ten to twenty years? Perhaps even longer. First, one needs to realize that such costs are imposed on 99% of the population for whom the acceptance of the ultimatum does not make any economic difference. Perhaps only 1% of the ethnically Serbian population, those who live in Kosovo, might lose some rights due to the non-economic requests contained in the EU proposal. One needs to be clear on that fact: rejection means loss of income for 99% of people in order to provide some, perhaps illusory, gains for 1%.

But what would be the consequence of rejection? Domestically, it will further stimulate the growth of nationalism. Not only--nationalists will say—that we knew all along that Europe does not want us and hates us, but now it is clear that they want to destroy us. Under such conditions all kinds of crazy schemes would be hatched up. Russia will support this craziness, not because Russia much cares about it, but because it has an incentive to create as many problems at any place in the world to make the West get busy working on something other than Ukraine.

There would be thus an explosion of nationalism under the conditions of reduced GDP. The loss could be, depending on the severity of sanctions, up to 5-10% of GDP in the first year. This would divide the public. Although currently all parties are in favor of the rejection of the ultimatum, and the pro-European parties, having been cheated by Europe many times, have taken a strongly anti-acceptance stance, seemingly stronger than the government, it is likely though that after a few years, the body public would seriously split between the “party of rejection” and the supporters of new negotiations with the EU. If such parties become of equal side and start violently accusing each other, it might end with a civil war. Since the West would have very few friendly parties to negotiate with in Serbia, and since Serbia is surrounded by NATO members, even a formal occupation of the country by NATO cannot be excluded. One should not forget that, right now, both Bosnia and Kosovo are NATO protectorates, and that the West can, by one single move, overthrow at any time the governments in Montenegro and North Macedonia. Moreover, NATO troops are in all these countries, plus in other border states (Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria, Hungary). Like in World War II, the very same countries could just march in.

Economic costs:

But as Serbia conducts more than 2/3 of its trade with the West, trade will, depending on the severity of sanctions, be significantly reduced, driving exports and GDP down. Foreign investments, again coming mostly from the EU, would dry out. Unemployment would increase, and real incomes will go down. Young people will increasingly leave the country. With an already very unfavorable demographic structure, it is mostly older people, of pensionable age, that would remain. Who would then earn money to pay these pensions?

Time is on the EU’s side:

The longer the situation lasts, the weaker would be the bargaining position of Serbia. EU will be unhappy, and would (in private) be aware of its ineptitude and unwillingness to contribute anything positive, but since it controls the media and the narrative, it will shift the entire blame on an “uncooperative Serbia” and “Russian agents”. And after 4-5 years, Serbia would show signs of willingness to negotiate but its relative position would be worse than it is today. So, it might lose five or more years and end up with the same or even worse deal.

Any Serbian President that signs over Kosovo is requesting his or her own assassination as it would be interpreted as the ultimate betrayal by many Serbs.

Dunno about you, but I really, really enjoy working from home, minus the incredibly dull Zoom calls that come with it. You may be different.

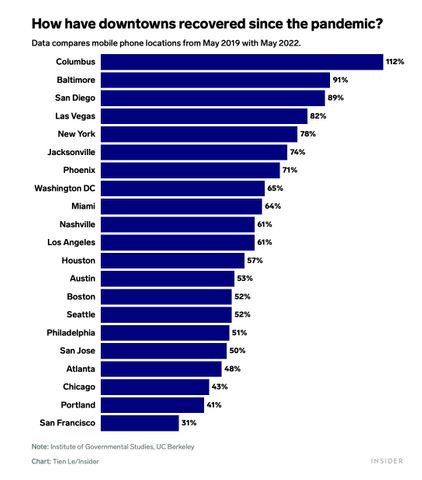

WFH is having a negative impact on American cities, particularly on commercial real estate owners and operators, and the businesses that rely on catering to people in the downtown core.

The nation’s office buildings aren’t as empty as they were before COVID vaccines became widely available in spring 2021. But they’re still far less populated than they were in 2019. A recent analysis of Census Bureau data from the financial site Lending Tree found that 29 percent of Americans were working from home in October 2022. In New York City, financial firms reported that only 56 percent of their employees were in the office on a typical day in September.

Full-time remote work has grown less prevalent since the worst days of the pandemic. But flexible work arrangements — in which employees report to the office a couple times a week — are proving stickier. A recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that 30 percent of all full-time workdays would be performed remotely by the end of 2022.

As Insider’s Emil Skandul illustrates in an excellent piece, these surveys and projections are buttressed by mobile phone data showing that, in virtually all major U.S. cities, foot traffic in central business districts is down substantially from 2019.

And collapsing office attendance rates are taking cities’ tax revenues down with them.

When only 50 percent of a company’s staff leave their homes in the morning, that firm’s desire for floorspace plummets. If storm-clouds appear on the economic horizon — like, say, a central bank dead set on slowing the economy to kill inflation — downsizing your office becomes the easiest way to cut expenses. Thus, as rising rates have laid tech low, San Francisco’s signature office towers have emptied out. In New York, meanwhile, Meta has ditched 450,000 square feet of office space. Across the nation as a whole, only about 47 percent of offices are occupied.

Chain reaction:

All this translates into plummeting demand for commercial real-estate, which translates into plummeting property values, which translates into plummeting tax receipts. A recent study from New York University’s Stern School of Business found that office values fell 45 percent in 2020, and are likely to remain 39 percent below pre-pandemic levels for the foreseeable future. If that projection proves true, it would wipe $453 billion in property values off American cities, thereby slashing a critical source of municipal revenues.

In New York City, property taxes are the single largest source of public funds, supplying one-third of the city’s tax revenue. Office buildings account for one-fifth of that sum. The declining market value of Manhattan’s major office districts alone cost the city $5.24 billion in revenue.

Transfer of commerce and wealth from the city to the periphery:

Remote work’s toll on cities does not end with its implications for property tax revenue. Enable suburban commuters to work from their dens several days a week, and you transfer all manner of smalltime commerce — lunch orders, after-work drinks, etc. — from the urban core to its periphery. And lost transactions mean lost sales taxes. U.S. cities expect their sales tax revenues to decline by an average of 2.5 percent in 2022, according to a survey from the National League of Cities. Last year, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer estimated that remote work would cost the city $111 million in sales tax receipts annually.

This is quite the nasty trap for cities.

We end this weekend’s Substack with a look at practitioners of Voudou in the Haitian Brooklyn Diaspora.

The unexpected move brought him the chance to expand his exploration of Vodou in a new context: the diasporic Haitian community in Brooklyn that practiced Vodou semisecretly. Generally, Vodou is practiced in the open air, deep in the countryside, but the constraints of the urban environment forced worshippers in New York to hold ceremonies in basements, out of public view. Over time, he gained the group’s trust and was invited to glimpse a way of life that is notoriously tight-lipped, holds on to remnants of a colonial past, and openly performs feats that most would consider pure magic.

From Haiti and its diaspora, Chery has drawn a portrait of a religion and way of life. His powers of observance offer a different view than the distorted perceptions that pervade pop culture’s appropriation of Vodou. Chery’s photographs situate a distinctly new-world spirituality formed from the syncretic mix of West African Vodun and Roman Catholicism. Vodou hinges on the mystic connection between practitioners and the loa — ethereal entities somewhat like saints or angels — that are called down to possess a human being and offer advice, healing, and power. Whether one hopes for financial success, recovery from an ailment, or even a spiritual “spouse,” the loa and their actions are understood to be of help in all aspects of human life. Like in Haiti, the Brooklyn ceremonies focus mainly on the possession of practitioners by the loa; however, space constraints and local laws (around, for example, the ritual killing of livestock) have forced practitioners to innovate.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

For paid subscribers, we are now testing out the chat feature on both Apple and Android phones. If you want to participate, read here.

"Not least, by adopting Westernism, this kind of new left can for once hope to be not just on the right but also on the winning side, American military power promising them that this time, finally, they may not be fighting for a lost cause."

First time as tragedy, second as farce.

European westernists such as the German Greens strike me as something akin to ideological janissaries, wholly converted to a foreign faith that demands implacable hostility to the interests of their own nation.

Hit the like button above to like this entry and use the share button to share this across social media.

Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so (be nice!), and please consider subscribing if you haven't done so already. We are now testing out the chat feature on both Apple and Android phones. Learn more here - https://niccolo.substack.com/p/fisted-by-foucault-subscriber-chat