Introduction: "Healing the Mutilated Victory" - Italy "Cheated" by Woodrow Wilson

FbF Book Club - The Fiume Crisis: Life in the Wake of the Habsburg Empire

My historical interests work in cycles; I’ll pick some subject up and get thoroughly engrossed by it, then put it down, and then re-visit it in a year or two when newer material becomes available, giving me the opportunity to view it through a new lens. This is how I don’t burn out on key subjects of interest. It is not intentional on my part, but instead became a natural process over time.

A fun party game is to ask people in which historical period would they choose to visit if they were granted access to a functioning time machine, but only once. My answer would be Interwar Europe, which some of you by now would have guessed based on the content up on this site. It’s distant enough now to allow for a significant amount of objective evaluation, but still within touching distance today due to how relevant events from that time in history remain. Whether it be Civil War Spain or the Bavarian Red Republic (both of which I’ve covered here in the past), there’s something about the extremism, and urgency, of that era that continually fascinates me to this day. I never grow tired of learning more about it.

I know quite a lot about Spain, Germany, the Soviet Union, the UK, Italy, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia of the two decades between the First and Second World Wars, but France of that era is relatively foreign to me, although nowhere near as alien as Interwar Poland, a terra incognita in my mental map that I hope to rectify in due time.

In January of 1917, 317 million Europeans were living in four empires that would be tossed into the dustbin of history less than years later. The great calamity that we call The First World War saw to it that industrial-scale mass killing caused by tactics being rapidly outpaced by technological innovation resulted in the dissolution of the Russian, German, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian Empires. A gigantic vacuum was thus created beginning with the Russian Revolution in which nations, cultures, societies, legal systems, and economies were unmoored from what were thought to be stable and durable imperial polities only a few years prior. This was the Great Upheaval that few could have imagined coming about from a war that was supposed to be over by Christmas of 1914.

A consolidated Europe gave way to a more fractured one. The collapse of the Russian Empire gave birth to the USSR, but also to Finland, the Baltic States, a sizable chunk of what would become Poland, and also witnessed the stillbirth of an independent Ukraine. The end of the Second German Reich completed the resurrection of Poland, as well as permitting the doomed Weimar Germany to arise from what remained of it.

It was the stunning end of the Dual Monarchy that left all of its citizens proverbially lost at sea, seeking an anchor to tie themselves to while in a state of panic and existential dread. The Austrian half of the Habsburg Empire was partitioned between its successor state, Austria, Italy, the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and with Czechoslovakia via Bohemia and Moravia forming the western part of this new country. The Hungarian Kingdom saw 2/3rds of its land mass become parts of Romania, and the aforementioned Czechoslovakia and Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. The remaining rump third became the independent state of Hungary, a fact that Viktor Orban never misses the opportunity to lament.

The smallest successor state of that global catastrophe was the independent city-state of Fiume, located on the northeastern coast of the Adriatic Sea in today’s Republic of Croatia. Fiume, a port city of some fifty thousand souls, was 95% Roman Catholic, but was very mixed in ethnic terms. The Dual Monarchy did not break down census results by stated ethnicity, but instead used “primary spoken language”, which can be used in most cases (like the following one) as a proxy for the local population. Per the census of 1910:

The Italians were a plurality, and formed the urban and commercial elite of the city. Croatians were almost entirely working class (which becomes important in WW2), and largely resided in the suburbs. The presence of Magyars may surprise some here, but Fiume was Hungary’s port city i.e. access to the open seas. Fiume permitted easy access to the Danubian Basin by train for shipped goods and vice versa, unlike Trieste, which was blocked from servicing that region by the imposing Alps. Fiume also had smaller minorities such as Brits and Jews, with the latter forming up to 1.5% of the population, but heterodox, as some identified with the local Magyars, others with the Germans, and still others with the Italians and the Croats. A polyglot trading port for a that most polyglot of European empires.

First, A Note

Fiume is the Italian word for ‘river’, and the current official name of the city, Rijeka (Ree-ye-kuh), means the exact same thing in Croatian. It’s a horribly unoriginal name that denotes that the original settlement bearing that moniker was built on the site where a river flows into the Adriatic Sea. For the purposes of this book club, we will use Fiume in place of Rijeka, just as the book does (except for the following part below). Unlike the book, we will use the name ‘Yugoslavia’ to denote what was officially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes from 1918 to 1929 (when the name was changed to the much better known variant), except in a few specific cases.

This is what the city of Rijeka looks like today (background) as taken from above the tourist town of Opatija facing southeast across the Bay of Kvarner. Rijeka has long been a port town and is geographically isolated from the interior by the mountain range that you can see further in the background, mountains that are nowhere near as high as the Alps north of Trieste. Today’s Rijeka is commonly seen by Croatians (and others from the ex-Yugoslavia) as a very liberal, somewhat red, and anti-ethnonationalist city, a holdout from the communist regime that ended some 35 years ago.

It is also somewhat isolated in terms of political geography, with its hinterland to the east, south, and southeast being populated by some of the most nationalist voting blocs in the country. Its population finds more common ground with voters along the coast to the north and to the northwest on the Istrian Peninsula. The city is now 85% Croatian in composition, with small minorities of Serbs, Bosnian Muslims, Slovenes, and even Italians. The great demographic shift in Rijeka took place immediately after the completion of WW2. It is also important to note that its political colouring (that of an “anti-fascist city”) derives from the conflict between the Italians and Croatians and other Slavs.

Lastly, I want to point out that I do have an ethnic bias regarding this topic, but I think that I can do a good job in straining towards the maximal amount of objectivity that it permits. You can let me know if I achieve this goal when we wrap up this book club entry.

Anyway, let’s return to Fiume……….

Versailles, Woodrow Wilson, and the Vittoria Mutilata

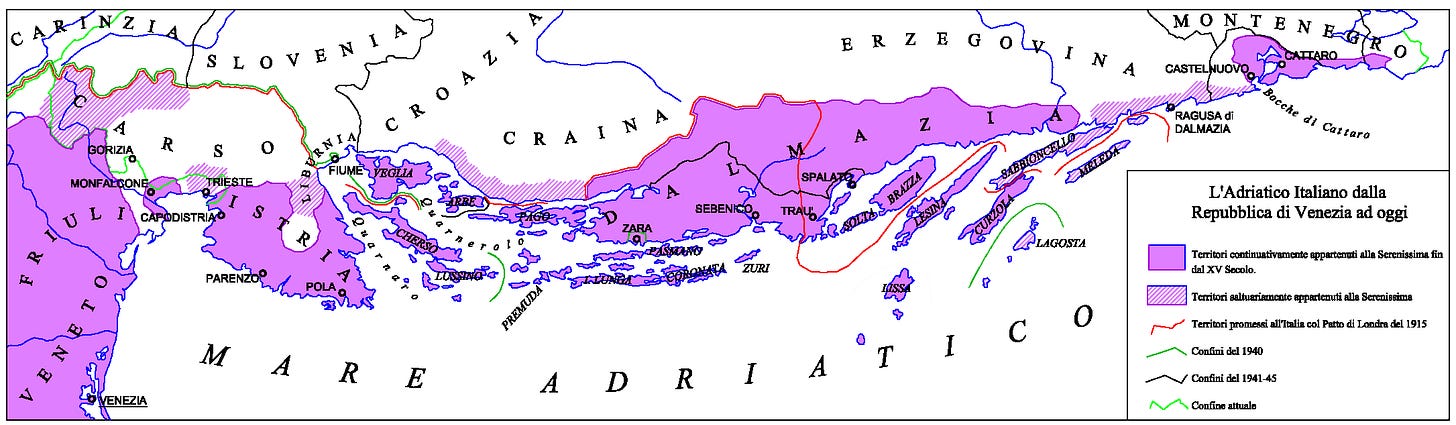

The Kingdom of Italy was a late entry into WW1. Despite the general public sentiment being one of desired neutrality, the Triple Entente dangling the most delicious carrot in front of Rome to tempt it into joining their fight against the Central Powers: that of great territorial expansion for Italy reminiscent of the old Venetian Empire, and an echo of the Roman one too. Here’s what the secret Treaty of London (1915) promised the Italians if they joined the war on the side of Paris, London, and Moscow:

Quite the score!

For the purposes of this book club, the following map is much more important:

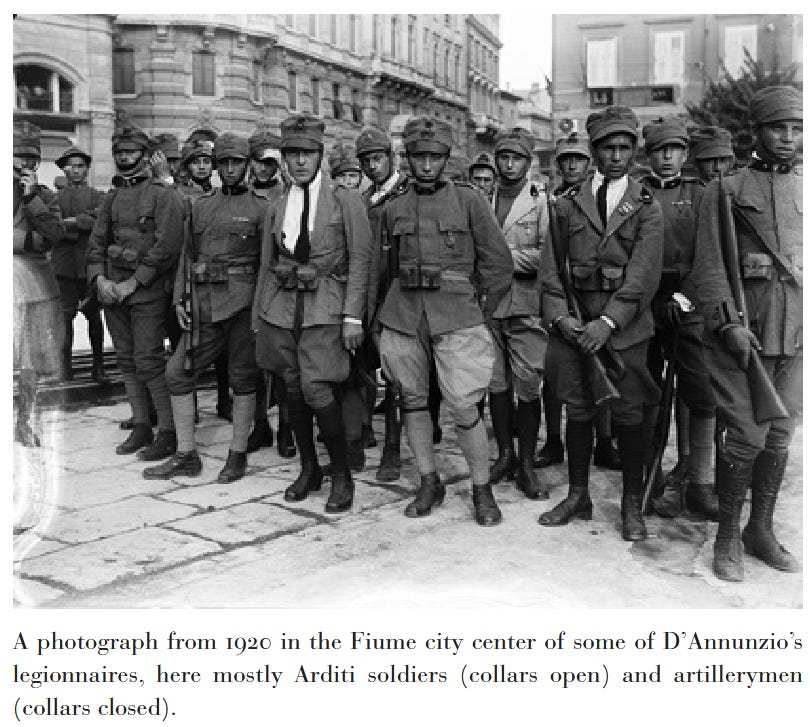

The yellow portions (going from west to south-east are South Tyrol, Friuli-Giulia-Trieste, Istria, Kvarner, Northern and Central Dalmatia) were pledged to the Italians should they open up a front against Austria.1 All these areas minus Dalmatia (excluding its then-capital, Zadar) were heavily populated by Italians. There was one problem with this: Istria, Kvarner (where Fiume is located), and Dalmatia were also heavily populated by Croatians, and in a few locales, Slovenes.

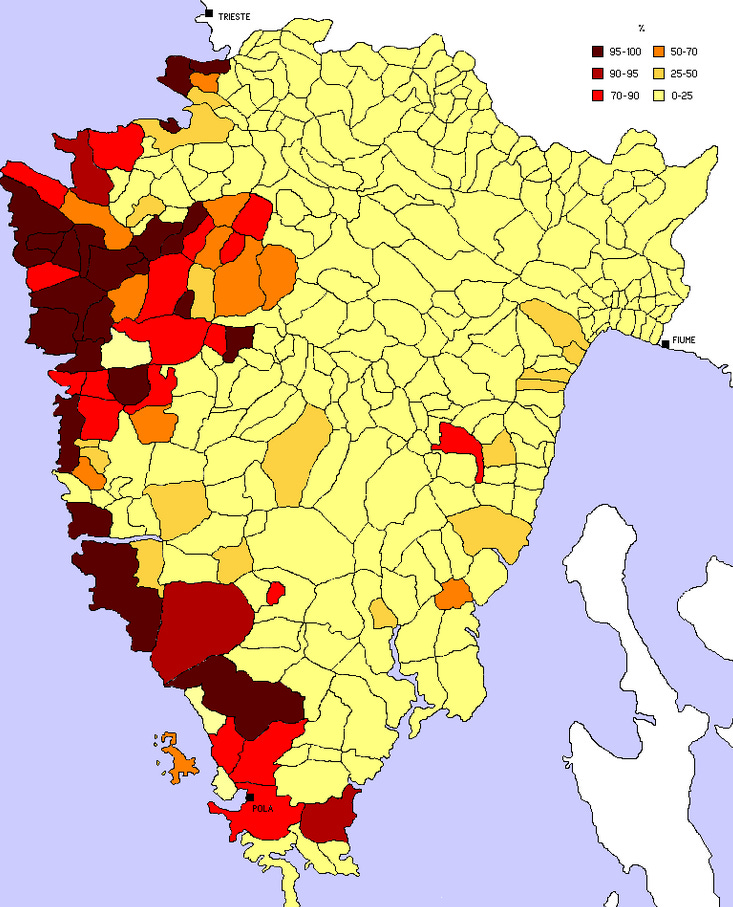

Another map (this portion is map-heavy for necessary reasons):

Harkening back to the days of the Venetian Empire, a lot of its geography was used to demarcate where the future borders of the Italian Kingdom would be in the case of an Entente victory. The Treaty of London granted the Italians everything within the red lines, but only received land within the green lines (please note the location of Fiume on the map).

The above map from 1910 shows the percentage of people who spoke Italian on a daily basis in Istria and Kvarner (with Fiume the east). A lot of Slavs residing in these areas made Italian claims to these lands not as clean cut as they would have liked them to be.