Chapters 4 and 5: "Open Fire on the Enemy" & Triumphant Failure

FbF Book Club - Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (Okrent, 2010)

Previous Entry - Chapter 3: The Most Remarkable Movement

We’re going to keep this entry lighter and also shorter in length, because the two chapters being covered describe how the Temperance Movement (now led by the Anti-Saloon League) went national based around a coalition of “racists, progressives, suffragists, populists, and nativists”. I want to get to the more interesting parts of this book, but there are some important highlights that we shouldn’t skip over before doing so.

Prohibitionists faced a big problem: much of the funding of the US Government came from taxes on alcohol. In the post-Civil War decades, that figure was around 20-40% of the overall federal revenue generated. Tax on alcohol was re-introduced by Lincoln in 1862 to pay for the Union’s war efforts, and it also helped finance the Spanish-American War at the end of the 19th century. So reliant was the federal government on taxes on alcohol that the brewers and distillers learned to love them, because they viewed this as the best bulwark against the Temperance Movement. If alcohol sales were banned, the federal government would be starved of money.

Okrent:

By 1910 the federal government was drawing more than $200 million a year from the bottle and the keg—71 percent of all internal revenue, and more than 30 percent of federal revenue overall. Only external revenue—the tariff—provided a larger share of the federal budget, and by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century the tariff’s continuation was the most intensely debated issue in American public life. It would be hard enough to fund the cost of government without the tariff and impossible without a liquor tax.

Looking at it objectively, all the Christian activists saying prayers as part of the Temperance Movement did seem to bring God on their side. Not only did a strange confluence of events manage to create a coalition of “racists, progressives, suffragists, populists, and nativists” to popularize their efforts, a populist reaction to the so-called “Gilded Age” and its newly-minted millionaires made the case for a national income tax, a tool that could plug in any financial hole left by Prohibition. Call it another stroke of luck or an Act of God….it doesn’t matter. Everything was working towards the benefit of the Temperance Movement.

On the push for a National Income Tax:

For the progressives, it was an obvious way to enhance the power and effectiveness of government. For many of the racially motivated prohibitionists of the South, whose populist anger was monochromatic but nonetheless real, it was a way to avenge Reconstruction by striking back at the economic and political imperialists of the North.

The big day for the ASL was December 10, 1913 when thousands upon thousands of people descended on Capitol Hill to present its petition for Prohibiton to Congress:

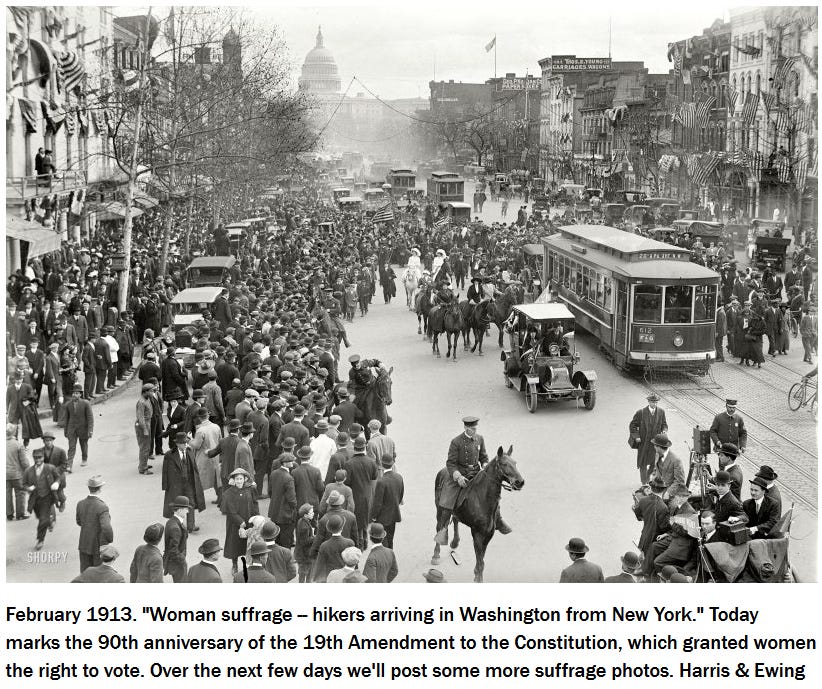

But no one could challenge the impact of the spectacle that unfolded in Washington when the ASL presented its petition. Washington in the late autumn of 1913 was filled with mendicants seeking the charity of Congress. Two weeks after a national meeting of suffragists was convened in the capital (the Washington Post had headlined its front-page story “Fair Cohorts Meet”), and just two days after the International Antivivisection and Animal Protection Congress was gaveled to order (featured speaker: William Jennings Bryan), Washington was occupied by the dry armies. From one mustering point fifty young girls dressed in white led a long column of women from the WCTU; from another marched the men of the ASL, representing all forty-eight states. After the two parades merged on the steps of the Capitol they presented a petition demanding a constitutional amendment to the men who would introduce it in their respective chambers: in the House the flamboyant Richmond Hobson of Alabama, and in the upper chamber Morris Sheppard of Texas, a Shakespearean scholar who was one of the Senate’s leading progressives. Thousands of bystanders had left the city’s sidewalks to follow the two parades to the Capitol. Apart from presidential inaugurations, Capitol guards told reporters, it was the largest crowd ever to gather on the building’s steps.