Chapter 3: The Most Remarkable Movement

FbF Book Club - Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (Okrent, 2010)

Previous Entry - Chapter 2: The Rising of Liquid Bread

The United States of America is not only a vast country geographically with a massive population, it is also a country of continuous change, whether culturally, economically, socially, or demographically. Yet there are some threads that do reach back to its earlier times, one of the most notable being the progressive one that began in New England prior to the American Revolution.

The third chapter of this book starts out at Oberlin College in the first half of the 19th century. Many of you are familiar with Oberlin because it is associated with some of the more progressive currents in US politics today. The fact of the matter is that Oberlin was progressive since its founding by two Presbyterian clergymen in 1833. It is a progressive institute by design. Frances Willard, a star in the earlier days of the Temperance Movement was the product of two Oberlin graduates. The Reverend Howard Hyde Russell, a transplant from Iowa, was drawn to Oberlin, Ohio where he went on to form the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), the organization that was most responsible for lobbying the US Government to enact Prohibition:

The Anti-Saloon League may not have been the first broad-based American pressure group, but it certainly was the first to develop the tactics and the muscle necessary to rewrite the Constitution. It owed its success to two ideas, one core constituency, and an Oberlin undergraduate who sat in the front row of the balcony of the First Congregational Church on a June Sunday in 1893 and heard Russell outline his plan to deliver the nation from the death grip of alcohol.

The Anti-Saloon League (founded in 1893) decided to take a radically different approach to lobbying for Prohibition than the Woman’s Christian Temperance Movement (WCTU) that came before it. Where the WCTU would involve itself in all sorts of causes in order to create a vast coalition that would support its drive against the production and distribution of alcohol, the ASL chose an approach that was totally the opposite; a laser-like focus on the single issue of Prohibition:

“The Anti-Saloon League is not in politics as a party, nor are we trying to abolish vice, gambling, horse-racing, murder, theft or arson,” one of its early leaders said. “The gold standard, the unlimited coinage of silver, protection, free trade and currency reform, do not concern us in the least.”

This was their strategy, one that allowed them to avoid the pitfalls of internal dissension that plagued the WCTU due to it having so many different groups at cross-purposes with one another. Politically agnostic, they aimed to control the swing vote in all elections, allowing them to use that as leverage with candidates. Regarding Russell: “…..[he] liked to cite rail baron Jay Gould’s credo—that he was a Republican when he was in Republican districts, a Democrat when he was in Democratic districts, but that he was always for the Erie Railroad.” This was pragmatism over idealism.

Russell was also lucky; he could rely on the Baptist and Methodist churches as the bedrock of his movement, and with its parishioners he could mobilize in massive numbers:

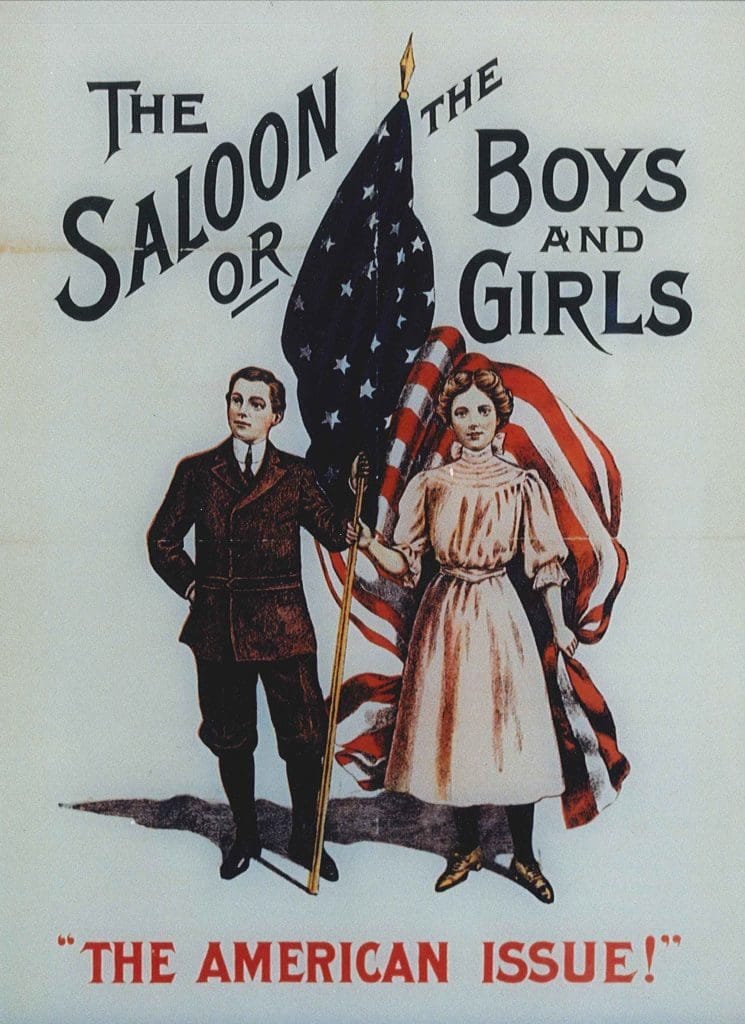

To gather the support needed to fund the group’s efforts and to line up those 10 percent of the voters who could tip the balance on election day, Russell and his colleagues mobilized the nation’s literalist Protestant churches and their congregations. Any pressure group would be fortunate to be blessed with a constituency like this one. It was scattered across the American landscape, yet easily reached when there was a message to deliver or an action to initiate. By its self-definition, it wore the mantle of moral authority. In its religious ardency, it was prepared for apocalyptic battle. The Anti-Saloon League was, its own slogan affirmed, “the Church in Action Against the Saloon.”

The leadership, the staff, and the directorates of the ASL and its affiliate organizations were overwhelmingly Methodist and Baptist. Clergymen occupied a minimum of 75 percent of the board seats of any state branch.

The ASL had a political project with a very large in-built constituency fired up by a clear and simple moral message. Russell had picked up a $1 million bill off of the sidewalk. With the WCTU lamenting the death of its leader, Frances Willard (and building up a Cult of Personality around her), the ASL had quickly moved ahead of it and became the leading organization fighting alcohol production and consumption.1 All he needed now was a general to marshal these resources to spread the Gospel of Prohibition across the whole of the USA.

Enter Wayne Bidwell Wheeler.