Chapter 6: Party System and Bürgerwehr Crisis

FbF Book Club: Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965)

Previous Entry - Chapter 5: Council System and Cabinet Crisis

Here’s how we ended the previous entry:

While reading this chapter and the one previous to it, I was left wondering what the radicals were up to, as they seemed to have disappeared from the story altogether. Just in the nick of time, they pop up to produce some rioting and street violence, just to remind everyone that they are there, and that they are organized, and ready to pounce:

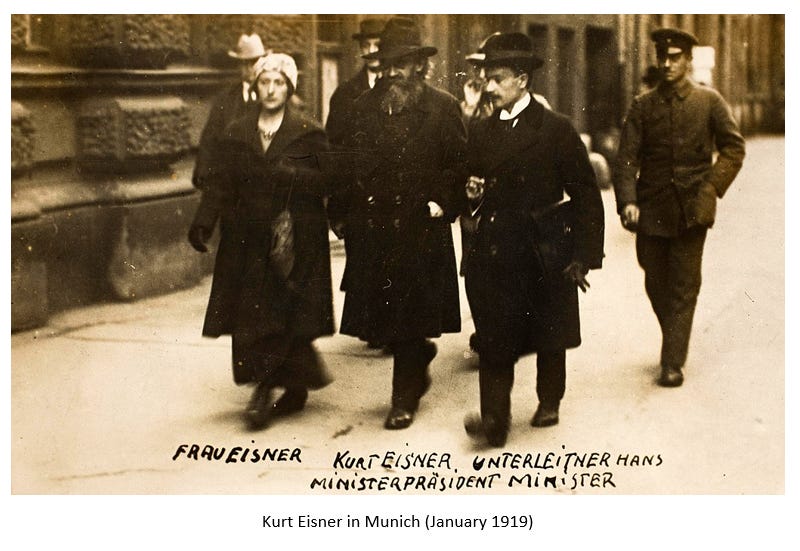

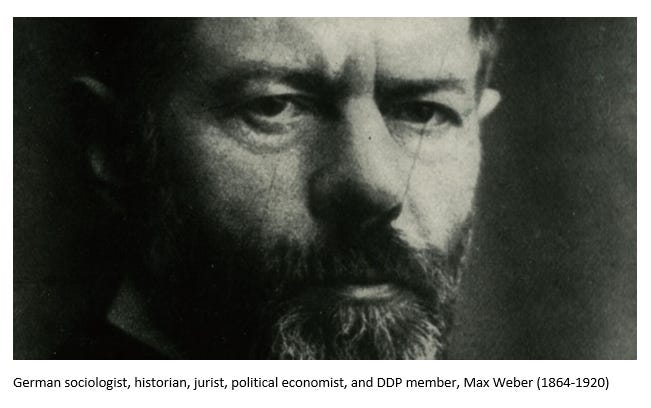

It was this knowledge, coupled with the apprehension in some quarters about the future of the council system, which produced the first serious recurrence of radical discontent since the night of the Munich Putsch. A new mood of belligerence became evident on the evening of December 5 at an open meeting in the Wagnersaal, where a political address in favor of the National Assembly by Max Weber was repeatedly interrupted from the floor until the speaker was unable to continue. Twenty-four hours later a night of rioting and confusion showed that the street was once again a political factor. Apparently without pre-arrangement, two separate public meetings erupted into the city in a spirit of protest. A party of nearly three hundred men broke into the residence of Erhard Auer, roused him out of bed, and obtained his written resignation at the point of a gun. Meanwhile, anarchist Erich Miihsam and another group seized several of Munich's leading newspapers, assumed editorial control, and granted ownership to the astonished typesetters.

Recall that Eisner had a) for years positioned himself to the left of the SPD, but to the right of the radicals, engaging in a very delicate balancing act, and b) been warning about the radicals and their threat to the take over the November Revolution.

It is in this chapter that an unforced error by Bavarian SPD Chief Erhard Auer allowed for the radicals to reassert themselves via the council system, and pose a threat to the Bavarian People’s Republic. This will be the main focus of this entry, but first we will get the political jockeying for position out of the way in order to clear the path for it.

December 1918-January 1919 Political Topography

SPD

Led by Erhard Auer, the Bavarian branch of the Social-Democrats was for all intents and purposes well-placed to inherit the government after the upcoming Landtag Elections set for January of 1919. Not only did they have the strongest organization of all political parties, they also had control over the vast majority of the labour unions (with the additional benefit of their mobilization on behalf of the party), and they were able to point in their role in not opposing the November Revolution, but also being a coalition member in its first provisional government. Lastly, they could also point to the role being played by the national party in Germany in forming the first post-war government in Berlin.

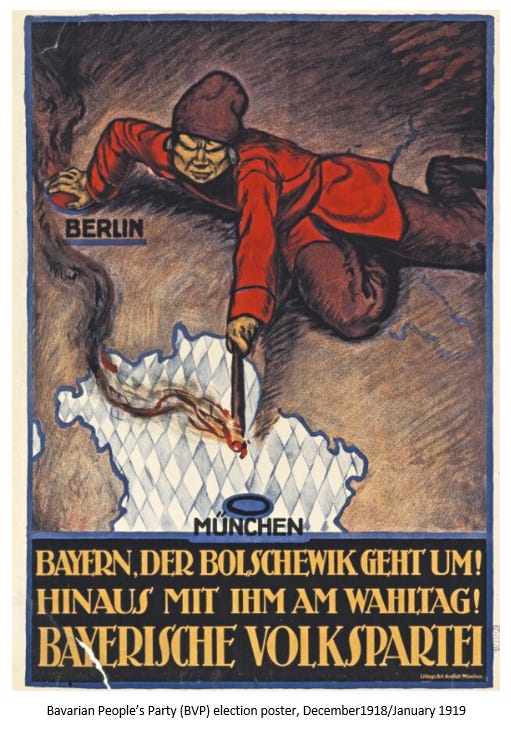

BVP

Alongside the SPD, the Bavarian People’s Party (BVP) was one of the two largest political parties in Bavaria at the time. The newly-formed BVP arose from the ashes of the Zentrum, the party of Catholic Monarchism in the pre-war era. The natural ruling party of Bavaria, its ties to the ancien regime and the lost war meant that its popularity had taken a hit among the people, enough to give the SPD first place in election projections. The BVP was the only party in favour of a restoration of the Wittelsbach Dynasty, although this position was not formalized nor broadcast widely as it was far from an opportune time to push for restoration. Murmurs of Bavarian separatism were still audible in its ranks, but federalism was by far the majority stance within the party.

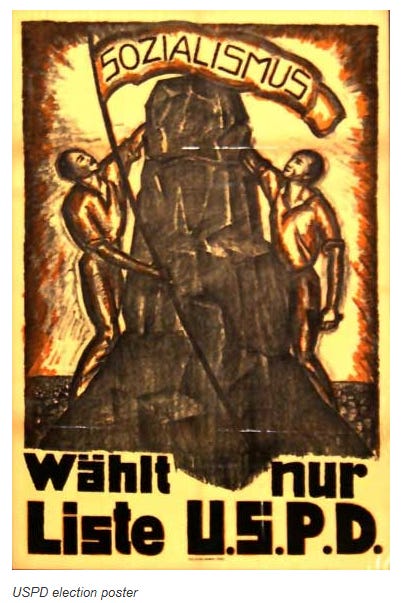

USP

Eisner’s Independent Socialists could point to being the spearhead of the November Revolution and could also trumpet the pro-labour changes it had initiated since then (such as the eight hour workday), but it lacked the strength, depth, and wide popularity of bot the SPD and the BVP, as it was largely a party of urban intellectuals in a land that was still highly rural and conservative. The USP needed coalition partners, with the SPD foremost among them, but found their advances unrequited. They themselves knew that they would not perform well in the Landtag election, and managed to find an ally in the BBB (Bavarian Peasants’ League) only after watering down their proposals for the socialization of the agricultural sector.

DDP

The German Democratic Party (DDP) inherited the mantle of the pre-war Liberals, and were more than happy to entertain a coalition with the SPD as both sought to prevent the return of the Catholic Monarchists to power, while rejecting the socialization of the Bavarian economy found to the SPD’s left (and toyed with by Eisner). They, like the SPD, were adamant federalists, upset with Eisner’s disastrous foray into national politics in Berlin where he brought up the threat of reigniting Bavarian Particularism.

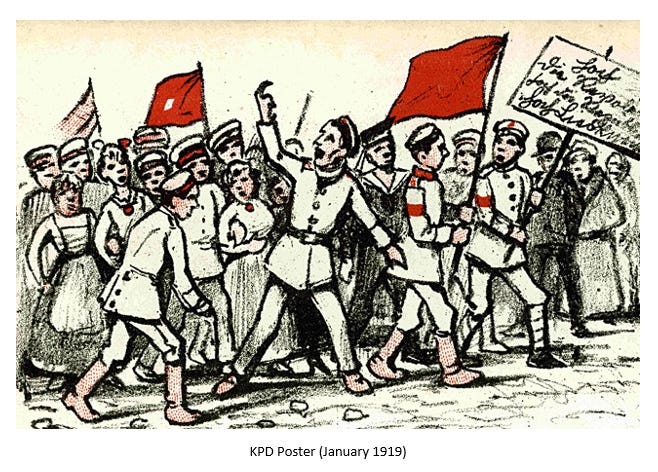

Spartacist League/KPD

Lurking in the background was the tangible threat of radicalism from the far left, but as Mitchell explains: “There is little….that can be said with precision about the development of radicalism in Bavaria after November 7, since neither its strength nor its importance was strictly measurable”. Rejecting the National Assembly in Berlin and party politics altogether, these radicals took inspiration from the Bolsheviks, seeking to spread “Global Revolution” to Bavaria. The Bavarian chapter of the Spartacist League was only set up on December 11th when its emissary from Berlin, Max Levien, arrived with instructions on how to “unite internationalist and the local elements of potential radicalism in Munich”. They had quickly concluded that the revolutionary councils would be ineffective until brought under the discipline of the Spartacist League (re-named the Communist Party of Germany, KPD, on January 1, 1919). The party had no appetite for participating in the elections for two reasons: 1. distaste for the “bourgeois” system, and 2) knowing full well that they would get annihilated at the polls. Their call was “all power to the councils of workers, soldiers, and peasants”.

The Crisis of Christmas Week

Bavaria was still experiencing peace, albeit under the cloud of shock from the loss of the war and the bloodless revolution that followed it. A new regime had been put into place, security was assured (for now), and the bureaucracy was won over via a guarantee of continuity. The docility of the Bavarians did have value after all. But would that reputed docility survive the upcoming Landtag election scheduled for the 12th of January? And could that docility prevail in light of violent outbursts that had broken out in Berlin?