Chapter 5: Council System and Cabinet Crisis

FbF Book Club: Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965)

Previous Entry - Chapter 4: Problems of Peace and Order

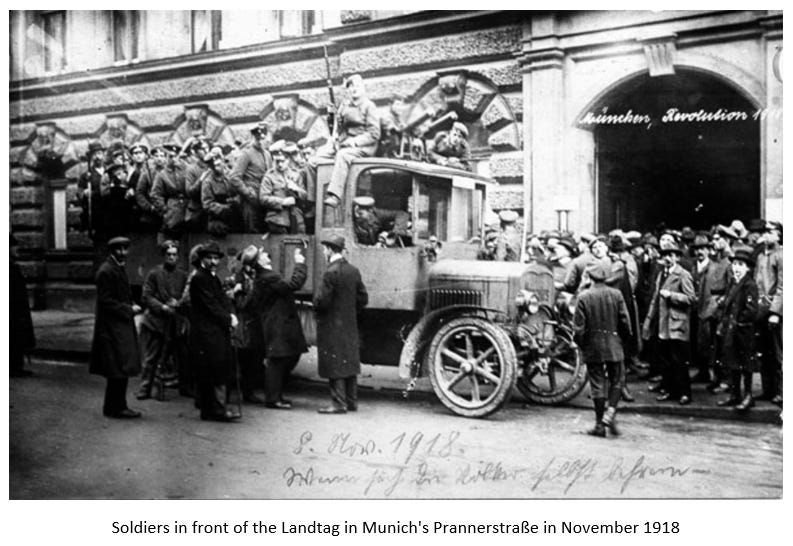

The fifth chapter of Mitchell’s book covers what would be the high water mark of Eisner’s revolutionary (or better yet, “revolutionary”) regime. Only three short weeks after the November Revolution took place, the honeymoon was already coming to an end.

After ensuring order in Bavaria, both in terms of security and the bureaucratic apparatus of state that came at the price of compromises that blunted the “revolutionary” aspect of the new regime, Eisner now tasked himself with guiding the formation of a “new spirit” that was to engulf the land. This new spirit would lead the councils (Soldiers’, Workers’, and Peasants’) to serve as the vehicles for “true democracy”, sweeping away the old forms that were aristocratic and not at all democratic. Defining the role of the councils and the power that would be accorded to them would lead to the very first cabinet crisis of the People’s State of Bavaria.

Eisner had returned from Berlin with the impression that the revolution was on safe grounds back in Bavaria. His attempt at inserting himself into German foreign policy had failed horribly, and questions were now being asked as to whether he was about to launch a drive for Bavarian independence, something that he had personally and publicly opposed for at least two decades and showed no signs of embracing any time soon. Nevertheless, by playing the “Bavarian Particularism” card in Berlin, he opened himself up to these charges.

At the same time, his vocal attacks against SPD representatives in Berlin upset his Bavarian SPD coalition partners, who voiced their anger via their local media outlets. Auer’s Bavarian SPD had joined the coalition because they saw the revolution as a fait accompli, and that only by staying in government could they influence its future course. The SPD had strong popular support (unlike Eisner’s semi-radicals), and knew the ins and outs of political horse trading (also unlike Eisner). Lastly, they had a strong level of support in the bureaucracy.

Councils

The backbone of the Bavaria’s revolutionary regime would be comprised of the revolutionary councils divided into three types:

Soldiers

Workers

Peasants

We have already seen how these councils were used to maintain order in Bavaria, specifically within the capital of Munich itself. These councils were not only to serve as vehicles for the participation of the people in democracy, but also to stave off more “Bolshevik” types, forestalling a second and more radical revolution.

These revolutionary councils popped up all across Bavaria in November of 1918, but were not all alike politically. In some places, radicals did indeed seize power (Augsburg), while in most other places they were comprised of much less radical elements who chose to work with existing authorities (Nuremberg). Still yet, there were other locales where the councils were quickly brought under control of the old authorities, completely defanged (hyper-Catholic Regensburg).