Chapter 10: The Soviet Republic and Concluding Remarks (Not Paywalled)

FbF Book Club: Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965)

Previous Entry - Chapter 9: The Second Revolution

“Kicking the can down the road” has long been a feature of politics, liberal democracies in particular. The Brits pride themselves (in their typical, self-deprecating manner) on “muddling through”. The American political system is built on compromise, whereby both sides are able to save face without resolving key questions, as they are left to a later date (think national debt, budget deficits, and so on). The French have for decades now done the same regarding their issues with certain immigrant groups, accepting the occasional flare-up of violence as an acceptable price to pay to avoid painful reforms.

Strong, stable, and wealthy polities are able to kick the can down the road seemingly endlessly. 1918-1919 Bavaria was neither strong, nor stable, and certainly not wealthy. For five months (beginning with the November Revolution), its political leadership could not resolve the matter of the councils, and what role, if any, they would play in the new regime. For five months, this can was kicked down the road. Bavaria ran out of road in April of 1919.

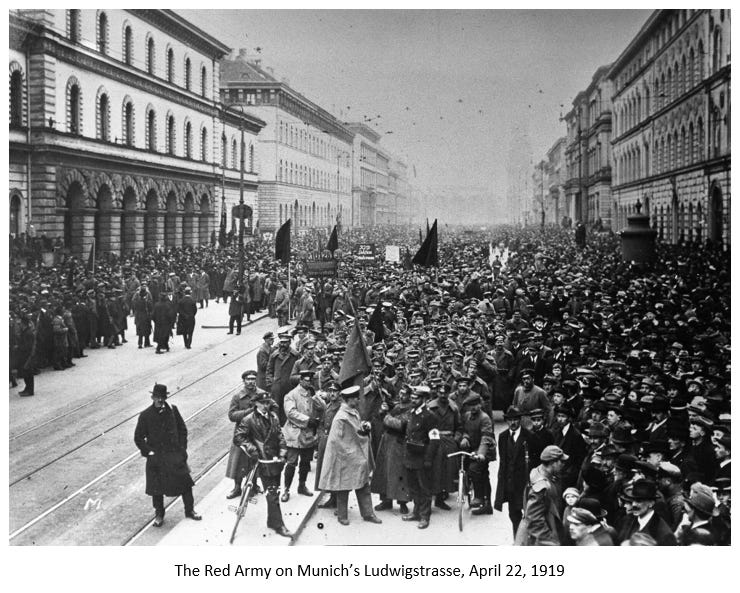

The radical communists had forced a showdown after months of agitation, violence, and effective organization. The ruling cabinet blinked, and fled to Bamberg in Northern Bavaria. They were quickly followed by the deputies who were to populate the Landtag.

Mitchell opens up this chapter by asking what he considers the most important question of this history: Just how was a soviet republic possible in Bavaria? He says that the reasons are too many, but highlights several key ones:

paralysis of the economy

inadequacy of security preparations

lack of firm support for the cabinet by the largest political party (BVP)

unsettling effect of developments outside of Bavaria

concerted agitation of a purposeful minority (radicals)

divided ambitions and ineptitude of political leadership

We can reduce these six causes into three:

collapsing economy

red wave moving through Europe

the opening up of a power vacuum in Bavaria’s capital, Munich

There were actually two soviet republics during April and May of 1919: the first was a “Pseudo-Soviet Republic” that lasted only six days, and failed to get the support of even the communists, despite it being declared in Munich on April 7. The second was the actual Soviet Republic (Räterepublik) that was under the strict control of the Bavarian communists, who were no longer led by Max Levien, but by a newcomer using the pseudonym Niessen, but was actually named Eugen Leviné:

But Levien was no longer the leader of the Bavarian Communist Party; that was now a man called Niessen. Eugen Levine, alias Niessen—born in Russia, raised and educated in Germany—had been one of two men designated by Rosa Luxemburg just before her death in January to represent the KPD at the first congress of the Third International in Moscow. Prevented from crossing the border, Levine returned to Berlin where he was given another assignment by the new chief of German Communism, Paul Levi: to travel to Bavaria and assume command of the Communist Party there. Levine had therefore arrived in Munich for the first time on March 5. By the end of that month, unknown to all but those on the inside, he had already made "fundamental changes" in the KPD's structure and policy. He assumed the editorship of the party journal, the Miinchener Rote Fahne, and on March 18 began daily publication. He managed a quiet purge of the party's executive committee, forcing out five of its seven members, retaining only the two original founders, Levien and Hans Kain.

Like Levien, Leviné was a Jew from Russia, a fact that would have tremendous consequences for Jews in Germany and beyond not too far in the future.

The farce that was the first soviet regime in Bavaria:

The first soviet regime in Bavaria lasted six days. It was a week of raucous and at times ridiculous confusion. Regulations, pronouncements, proclamations, orders and counter orders were drafted, printed, and distributed in hectic tempo. The press would be socialized along with the mines, the banks would be reorganized and so would the bureaucracy, special revolutionary tribunals would replace the courts, living quarters would be registered, foodstuffs would be confiscated, the bourgeoisie would be disarmed and the proletariat armed, the Red Army formed, the Soviet Republic defended, the International greeted, the World Revolution extended. And, as the new regime recognized, the Bavarian population would be bewildered: "Comrades! You do not know what a Soviet Republic means. You will tell it now by its work. The Soviet Republic will bring the new order."

The Bavarian Government-in-Exile (in Bamberg) was not sitting idly by as Munich and all the rest of Bavaria below the Danube River fell into the hands of the Reds:

"The regime of the Bavarian Freestate has NOT resigned. It has transferred its seat from Munich. The regime is and will remain the SINGLE possessor of power in Bavaria and is alone qualified to release legal regulations and to issue [administrative] orders. . . ." This manifesto had been signed by Johannes Hoffmann in Nuremberg on April 7, and as he sat in his office at the city hall in Bamberg a few days later, his only problem was to enforce it. Although his government-in-exile had been successful enough in its initial efforts to quarantine soviet rule below the Danube line, to regain the capital was another question. In the cities of northern Bavaria the excitement of the Soviet Republic's proclamation had lasted no more than a day or two: in Wiirzburg, Fiirth, Ingolstadt, Regensburg, and Schweinfurt there had been proclamations, crowds, "encroachments," and then a swift restoration of order. Nuremberg and Bamberg had remained quiet and loyal, while in the countryside the general reaction was either continued indifference or increased hostility to the whims of big city politicians. Only in the triangle bounded by Augsburg, Rosenheim, and Garmisch—an area of less than 2000 square miles in all—could Munich still claim precedence over Bamberg.

The Soviet regime(s) in Bavaria were not popular in conservative and Catholic Bavaria, despite its hold over the capital. What little popularity it had was whittled away by the draconian measures it took against its own citizens during its brief rule. The dividing line had been drawn, and civil war was inevitable. Making matters worse for the soviets was the fact that various red regimes in Northern Germany had already been snuffed out by the federal government, through the leadership of SPD politician and Minister of Defence, Gustav Noske, with the assistance of the Freikorps.

Hoffmann, the leader of the government-in-exile in Bamberg, wanted to extinguish the Soviet Republic without any aid from Berlin, and decided to approach the matter in three different ways, simultaneously:

total blockade of Munich (food, coal, etc.)

negotiations

military assault

Enter Ernst Toller: an unknown 25 year old poet who supported the declaration of a soviet republic in Bavaria, but who wanted to avoid bloodshed and was open to negotiations to prevent it. He was foisted into the official capacity of leader of the Soviet Republic despite not being aligned with Levien and Leviné.

The soviets drew first blood when an attempt by the Bamberg government forces to take Munich had failed:

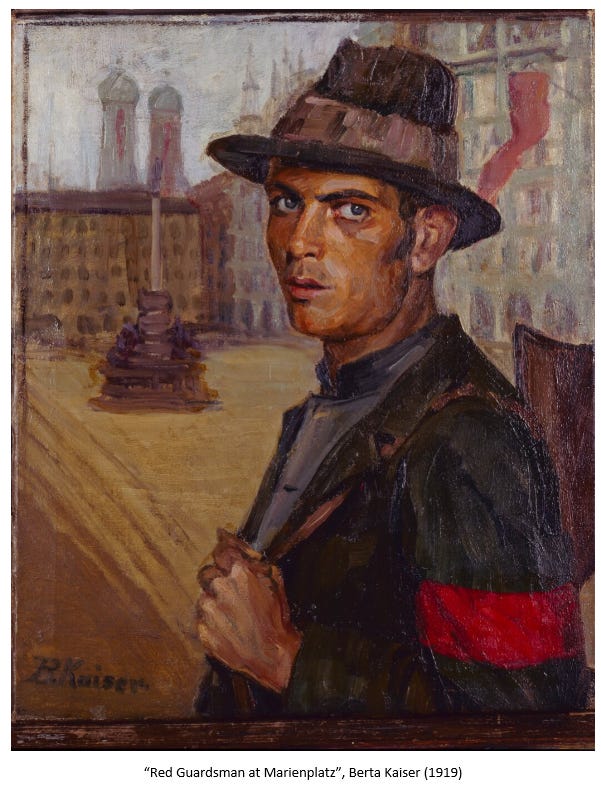

April 13 was Palm Sunday. Before dawn a detachment of the Republican Security Troops broke into the Wittelsbach Palace and arrested several members of the Zentralrat quartered there, among them Erich Miihsam and Franz Lipp. It was the kind of putsch-attempt for which Munich was to become famous, in which success would depend on the uncertain threat rather than the immediate presence of great armed strength. In Ingolstadt Ernst Schneppenhorst was standing by with six hundred men, awaiting word that the capital had been taken from within before moving in to secure its "liberation." He and Prime Minister Hoffmann had made this arrangement with Alfred Seyfferitz, who probably had no more than a few hundred reliables among his Security Troops inside of Munich, but who had agreed to make the first move against the soviet regime. By mid-morning a fresh layer of placards pasted on the neighborhood kiosks announced that the Zentralrat was deposed and urged the populace to avoid "starvation [and] civil war" by restoring the Hoffmann government. Sunday strollers prudently stayed away from downtown Munich when word was passed for soviet supporters to gather on the Theresienwiese that afternoon. Automobiles with armed soldiers packed inside and on the running boards moved through the streets. At three o'clock there was a fit of wild shooting on the Marienplatz, in front of the Rathaus: though several were wounded, the first fatality of the day was a sailor struck while playing billiards on the second floor of a nearby restaurant.

…….

Shortly after four o'clock the battle began and lasted into the evening. By nine o'clock no help had arrived and the terminal fell to the attackers, as the Security Troops escaped through the rear by train or scattered into the city. The total casualties numbered more than twenty dead and a hundred wounded. The Soviet Republic had survived; it was now a question of who would dominate it.

Soviet Republic of Bavaria 1 - Bavarian Government-in-Exile 0

Communist Rule and Red Terror

A collapsed economy and the blockade of Munich forced the soviets to immediately enact coercive measures to protect itself from the coming “reactionary” attacks. As per Bavarikon:

Munich's second Soviet government sought to establish a communist dictatorship. Through a series of arbitrary acts it attracted the deep abhorrence of the Munich population; massive fears of the establishment of a Bolshevik system spread. The communist rulers used means of state terror ("red terror") and indiscriminately threatened, intimidated and held members of the bourgeois camp hostage or put them under preventive arrest. In addition, cash holdings were confiscated, safe-deposit boxes were opened and the freedom of the press was blocked. New revolutionary tribunals were set up to eliminate counterrevolutionary activities. These actions were criminal in nature, but they were also massively exaggerated by enemy propaganda.

The “Red Terror” experienced by Bavarians in Munich during that fateful month would resonate for decades to come, and go far in explaining why Bavaria became as reactionary as it was during the Weimar Republic, and why the early NSDAP found such fertile soil there for its politics. Leviné, a Russian Jewish communist who had never set foot in Bavaria until the first week of March, became the face of the Soviet Republic as he was made its chief executive. His status as a foreigner and a Jew would also be very consequential.

The “Whites” (Bamberg Government-in-Exile forces) immediately set up a Volkswehr to try and snuff out the Red Republic, but were disastrously rebuffed at Dachau. Hoffmann and his cabinet were thus forced to turn to Berlin for support:

Gustav Noske promptly authorized 20,000 troops to move into Bavaria, of which 7500 were actually to arrive. The Wiirttemberg contingent numbered 3750, and the Volkswehr and Free Corps recruited in northern Bavaria (though not entirely comprised of Bavarians) totaled about 22,000—bringing the strength of the fully-equipped invading forces to nearly 35,000 men.

The Freikorps were on their way. Meanwhile, the Red Terror continued unabated. The Soviet Republic declared the churning of milk into butter or cheese to be “criminal sabotage against the regime”, for example. But this was minor in comparison to what else it was doing to its own citizens:

Because of the blockade, the Vollzugsrat found it necessary to order the confiscation of all available foodstuffs in the city. This resulted in the entering and searching of private homes by groups of armed men, and permitted thefts and violations of privacy which the regime (though it tried) was helpless to control. If the confiscations were an understandable and, therefore, not altogether unpopular measure (as when a certain countess was reported to be hoarding a bathtub full of eggs), most of the food obtained was consigned to provision the Red Army and never reached the population at large.

From Bavarikon on the taking and shooting of hostages:

On 26 April, radical supporters of the Soviet Republic took eight hostages and brought them to the Luitpoldgymnasium in Munich's Müllerstraße. Seven of them were members of the anti-Semitic and anti-republican Thule Society, which had been involved in the foundation of the German Labour Party (DAP) in January 1919. In 1920, the DAP was to become the NSDAP. On 30 April, members of the Red Army shot the hostages together with two Prussian soldiers in the courtyard of the grammar school.

This act sparked massive outrage in Bavaria and beyond, and served to “justify” the massive reprisals against the communists after the Soviet Republic was extinguished.

Weakening and Collapse of the Soviet Regime

Mitchell:

By the end of Easter Week, then, it was becoming evident to everyone acquainted with the facts that the Soviet Republic was neither economically viable nor militarily defensible. The result, as inevitable as anything can be, was the political collapse of the Communist regime. Opposition to "the Russians," Levine and Levien, had been mounting since April 13. Much of it was attributable to the calumny against "foreigners and Jews" which had earlier worried Kurt Eisner, but some it it grew from disagreement on specific military and economic measures. Ernst Toller had already had at least two serious altercations with Levine; after one of them he was briefly detained under virtual arrest but, being the "liberator of Dachau" and the closest thing to a genuine hero among the soviet leaders, he was released and allowed to continue his military command.

Toller did not mince words:

The third charge was frankly emotional: that "the present regime was," in Toller's words, "a calamity for the working people of Bavaria." His accusation was that Levine and Levien had made all too effective use of their Russian passports to gain their way with the radical leaders in Munich. "The great feat of the Russian Revolution lends to these men a magic luster. Experienced German Communists stare at them as if dazzled. Because Lenin is a Russian, they are assumed to have his ability. 'In Russia we did it differently'— this phrase upset every decision."

On April 27, a no confidence vote in the government passed and the soviet government collapsed.

The newly-created Red Army of Bavaria wasn’t having it and declared that it would defend the Bavarian Soviet Republic by force of arms:

“The Red Army was not founded as an instrument of politics but as an organ for the defense of the dictatorship of the proletariat and of the Soviet Republic against the counter-revolution of the White Guard. In accordance with this assignment, the General Command declares that it will defend the revolutionary proletariat—whatever the cost may be—against the White Guard, and will not allow itself to be forced into a betrayal of the social revolution by any faction, not even by the Factory Councils.” - Rudolf Egelhofer, Red Army Commander

May Day, the most important day in the communist calendar, proved to be the most fateful one for Bavaria’s Soviet Republic:

On the first of May Lenin spoke to an immense gathering at the Red Square in Moscow: "In all nations the workers have set foot on the path of struggle with imperialism. The liberated working class is celebrating its anniversary freely and openly not only in Soviet Russia, but also in Soviet Hungary and Soviet Bavaria." That same day the troops of General von Oven closed a tight ring around Munich and prepared for the final assault. There was a celebration in the city—an organized march of school children—yet for most of the day it was strangely quiet downtown, the streets almost deserted. The plan of the invaders was to wait until noon of May 2 before advancing farther, presumably so as to provide no martyrs for future May Day observances. But at that moment it was learned that ten hostages had been murdered inside Munich at the Luitpoldgymnasium. This was not only a wicked and futile act—it turned the civil war into a virtual slaughter.

Slaughter:

Some of the aroused invaders broke formation in the early evening of May 1 and began moving into the city with the avowed intention of giving it "a thorough cleansing." Resistance was quickly and ruthlessly broken. Men found carrying or hiding weapons were shot without trial and often without question. On the evening of May 2 only the main railway terminal and a cluster of military barracks remained to be taken. By the next afternoon the city was quiet again and the dead numbered over six hundred. The irresponsible brutality of the Free Corps continued sporadically during the next few days as political prisoners were taken and sometimes beaten or executed.

The Soviet Republic of Bavaria was brought to a bloody end.

Max Levien managed to somehow escape unharmed. Ernst Toller was sentenced to five years in prison. Eugen Leviné, seen as the face of the regime, was captured and put on trial. He was convicted of treason and executed on June 5, 1919.

Concluding Remarks

Modern histories tend to gloss over the various communist regimes that sprung up across Germany after its defeat in WW1. This does us a great disservice because it is impossible to understand the rise of reactionary politics in Germany without understanding the experience of Germans under red regimes, and the “red terror” that they lived through. The rise of fascism on the European continent was a direct reaction to these red regimes in Berlin, Bavaria, Hungary, and elsewhere. They did not arise in a vacuum.

The main reason why I chose this brief period in history and why I chose this book is to provide readers of this Substack an opportunity to see how a country actually falls apart. The volatile Trump Era (and visible signs of wear and tear in the USA) has led many people to believe that the USA is itself collapsing. As you all already know, I disagree with this assessment. When you look at the Bavaria of 1918-19, you see a collection of catastrophes that beset that land in rapid succession: significant deaths in a war that was lost but which many assumed was being won, rapid economic decline and collapse, power vacuum after power vacuum, erosion of physical security, inflation, energy blackouts, and so on. The USA of today is experiencing none of this crises that hit Bavaria during those several months. 1918-19 Bavaria shows us how it looks when a country falls apart, something that, in my opinion, is not happening in the USA today.

This ends this version of the FbF Book Club. Hit the like button at the top of the page to like this entry. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

I really, really enjoyed this history as it is quite complex and very dramatic.

Don't forget that Hitler was a socialist/Collectivist. His party only got 30% of the vote and Hitler was APPOINTED as Chancellor by Hindenburg, not popularly elected. And it was only after the Reichstag Fire (think Jan6th Fedsurrection) that Hitler was able to bamboozle complete power into his hands.

And the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was only possible because the Communists and NAZIs were not opposites but were Collectivist movements who saw capitalist Poland as their mutual enemy.