Chapter 9: The Second Revolution

FbF Book Club: Revolution in Bavaria, 1918-1919 (Mitchell, 1965)

Previous Entry - Chapters 7 & 8: Deterioration and the End of the Eisner Regime

Imagine being Eduard Auer, leader of the Bavarian SPD, on the morning of February 21, 1919. You wake up and smile, realizing that your decades’ old goal (capturing political power in Bavaria) is about to finally be achieved later today. You’ve marginalized the radicals in the council system, you have made Eisner a political zero, and you have ring-fenced the Landtag whereby the Catholics of the BVP cannot enter government. All that’s left is a few procedures in today’s opening of the Landtag and for the first time in Bavarian history, social-democracy will rule the land.

…and then fate intervenes: a right-wing radical named Count Arco-Valley pulls out of a revolver and kills Kurt Eisner, doing to him physically what you (and the Bavarian electorate) did to him electorally. Being assassinated proves to be a great career move for Eisner, and he becomes THE symbol of revolution in Bavaria, with many of his critics, detractors, and opponents overnight lionizing him.

Only a few hours later, a left-wing radical decides to take a shot at you. Luckily, you manage to avoid Eisner’s fate, but are left wounded and physically weak, and withdraw from public life for the next several years, just as you were about to conclude your life’s great achievement.

Arco-Valley’s stated aim of preventing a second revolution in fact did the opposite: it made it possible, as Mitchell explains. The transfer of power to the Landtag was forestalled, and the councils revitalized and further radicalized just as they were about to legally marginalized.

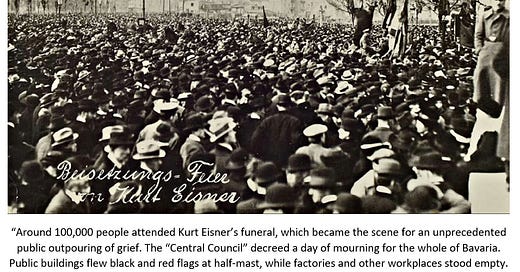

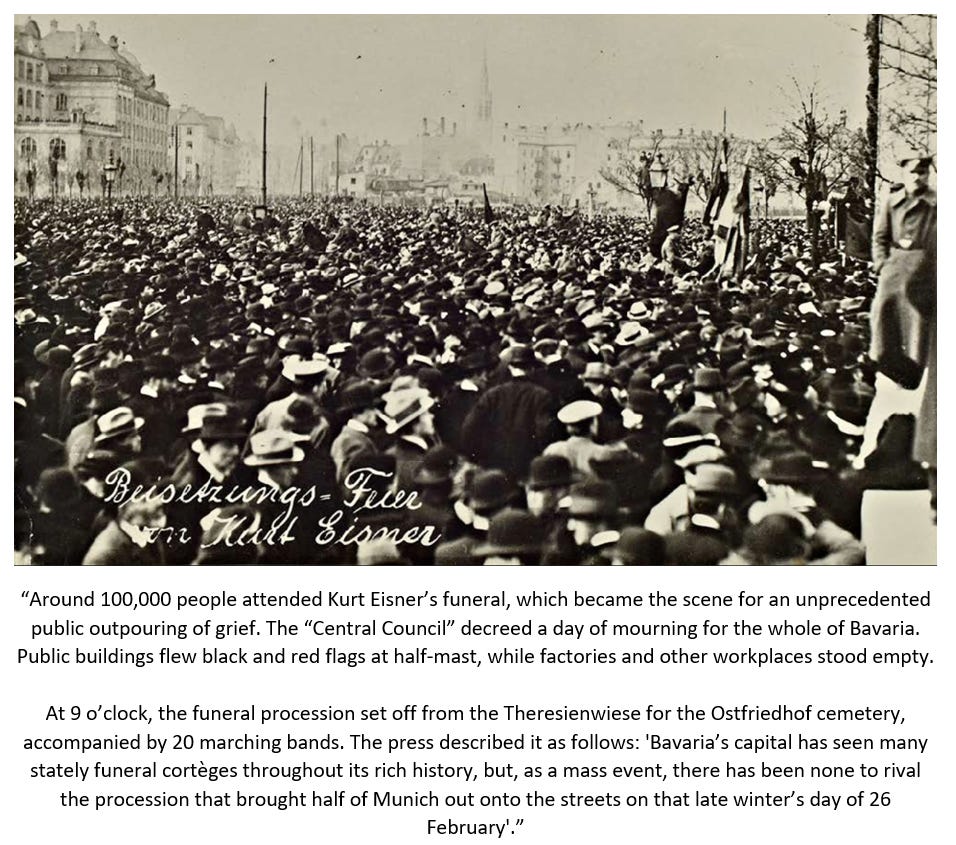

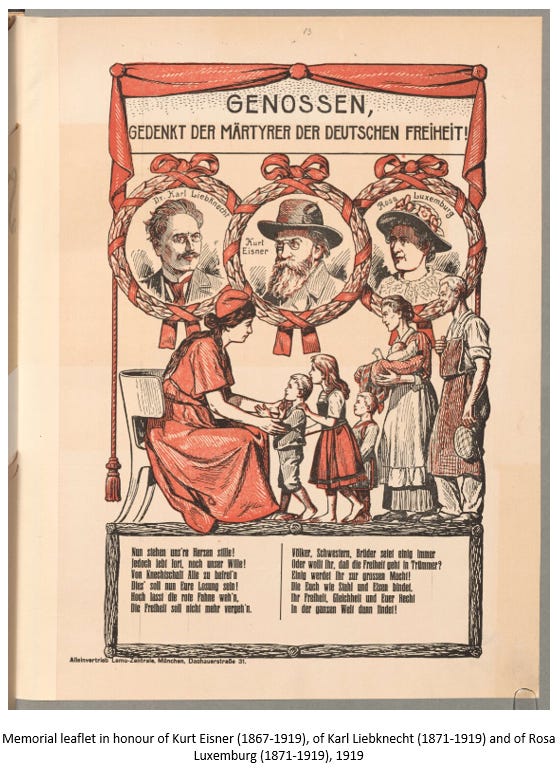

As mentioned, Eisner became a folk hero, post-mortem:

During the last weeks of his life Kurt Eisner had suffered one indignity after another. He had been humiliated at the polls, ridiculed in the press, badgered in cabinet meetings, and vilified as a Jew and a foreigner. Now it seemed suddenly that he was the noblest Bavarian of them all. Everyone claimed him as their own: the radicals, as martyr of the revolution, liberator of the proletariat, and champion of the council system; the others, as the man who had been on his way to the Landtag to acknowledge the restoration of parliamentary authority. The name of the man who had been so little known before the beginning of his premiership, and so little respected during it, was momentarily elevated to the status of a Bavarian folk-hero.

Left-radicals demanded that Eisner’s death be avenged. What his death managed to do was re-open the council question again, to the delight of these same left-radicals.

Making matters worse, cabinet members and parliamentary deputies fled the Bavarian capital, rendering the Landtag mandate “null and void”, at least in the eyes of the left-radicals of the council system, who then filled the power vacuum by convening meetings, declaring martial law, enacting a three-day general strike, and ordering a curfew. Munich was now radicalized and in the hands of the councils.