America and "Whiteness" - Part 1: The Early Americans (1776-1800)

Creating and Defining an American National Consciousness, In-Group/Out-Group Dynamics, The European as the Main "Other", First Census, Restriction to Whites Only

(Author’s Note: This series of essays will cover a sprawling subject that is complex, at times confusing, and always politically incendiary. As I am writing several essays and not a full-length book, some generalizations will have to be made as they cannot be avoided for the sake of maintaining a digestible length for readers. I am very aware that there will be exceptions to almost every point that I bring up. These essays will also satisfy almost no one. Thankfully, I am not in the job of satisfying others. Also, I am not advocating for any course of action to be taken by Americans. As a foreigner, it would be incredibly rude of me to do so. Lastly, this subject has always fascinated me, and hundreds of people over the years have asked me to state my views on the matter.)

"L'Italia è fatta. Restano da fare gli italiani" (“We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians.”)

-Italian Statesman Massimo d’Azeglio (1798-1866)

“Be British, boys. Be British!”

-final words attributed to Edward Smith, Captain of the sinking Titanic (1850-1912)

“I’m an American.”

-Law Professor and drafter of the RICO Act G. Robert Blakey (1936-) whenever asked what his ethnicity was

Charlie Kirk is the Founder and President of the conservative student movement Turning Point USA (TPUSA). This organization’s mission aims to “…identify, organize, and empower young people to promote the principles of free markets and limited government.” This goal makes it just another cog in what is commonly (and pejoratively) referred to as “Conservative Inc.” i.e. a way to make money by appealing to conservative values. Utterly predictable, thoroughly consistent, and quite unremarkable, they are a dime a dozen.

On August 23, 2023, Charlie Kirk made the following comment on Twitter: “Whiteness is great. Be proud of who you are.” This naturally set off a firestorm of commentary, ranging from outright support to advocacy for the elimination of “Whiteness”. All in all, very predictable.

This wasn’t the first time that Kirk has dipped his toe into the pool of racial politics. Even though he is a very common type in the world of Conservative Inc., he serves as a good weathervane to see where Conservative America stands at the moment. The fact that someone as mainstream as him is willing to cross over the line into racial politics and violate the principled “colourblindness” of US conservatism is an indicator that racial identity among Americans possessing white racial attributes present, and possibly on the rise as well.

Many of Kirk’s fellow conservatives were up in arms about his statement, insisting that pride in one’s race is “silly” or “destructive”, and even “anti-American”. “One should be proud to be an American, but not proud to be white”, was the general tone of argument from this cohort. This appeal to principle has a sound logic and a long history, but a nagging feeling that this very same principle no longer works in today’s USA lingers in the air.

Under a steady stream of attacks from academia, media, popular culture, and even politicians for an innate physical attribute that they possess, many whites in the USA are beginning to question just what it means to be an American today, and whether they should identify primarily with their racial kin in their own country, at the expense of the whole of the nation.

The question then becomes: are whites in the United States of America experiencing an ethnogenesis? The follow-up question is even more serious: if this ethnogenesis is actually taking place and eventually succeeds, where will this new ethnos invest its primary loyalty?

Beyond these two questions, we will need to explore the meaning of concepts such as nation, nationality, ethnicity/ethnos, national consciousness, citizenship, ethnogenesis, etc., and especially how they are viewed in an American context. We will discuss all of these concepts throughout the course of this series.

We will begin with a historical overview to try and answer the most important question of them all: just what is an American anyway?

Forging An American Identity

“The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations”

-President George Washington in his Farewell Address, September 17, 1796

Note: all references to “Americans” will be limited to the historical lands that have formed the United States of America for the intended purposes of this essay.

The natural starting point for this segment is 1776, when revolutionaries in the Thirteen Colonies declared independence from the British Crown. It was from this point forward that the citizens of the newly-formed United States of America had the institutions that allowed them to decide how best to identify themselves, who belonged to this new identity (and what this new identity denoted), and just as importantly, who did not belong.

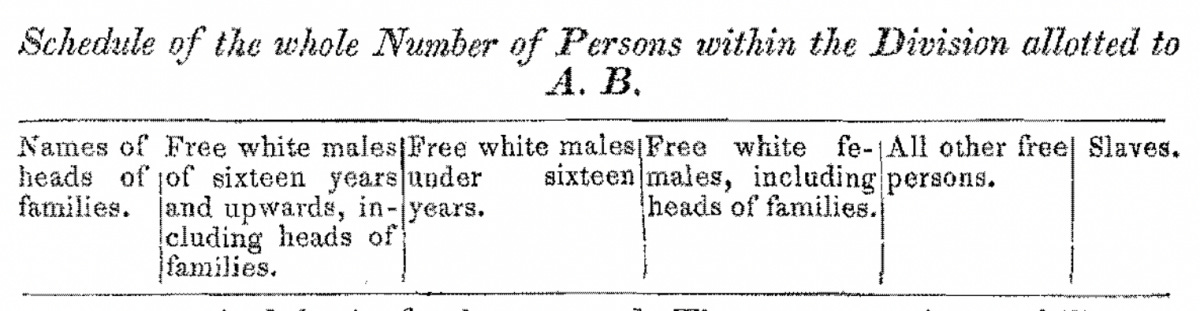

Stressing the fact that they were no longer British, President George Washington’s administration conducted the USA’s first census in 1790. Those counted were separated into five distinct groups:

Free white males age 16 and older

Free white males under the age of 16

Free white females

All other free persons1

Slaves

Native Americans who did not live among white people were not counted in this census.

What one immediately notices is that this first census broke down mainly along racial lines, instead of ethnic or confessional ones. This implies a difference in perception between these groups by the authorities (white women were separated out just like white males under 16 as adult males were seen as the engine of the economy and the source of military recruitment), one that was legally formalized.

Nor was “white” just a substitute for “British”, as we can see in this description of late 18th century USA:

The first federal census, conducted in 1790, found that a fifth of the entire population was African American. Among whites, three-fifths were English in ancestry and another fifth was Scottish or Irish. The remainder was of Dutch, French, German, Swedish, or some other background.2

As we can see, whites were those of European heritage.

This dovetails nicely with one of the first definitions of what is an American, as provided by the naturalized American author, diplomat, and farmer Jean de Crèvecoeur (J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur). In his wildly popular Letters From An American Farmer (1782), he defines an American as: “a descendant of Europeans who, if he were "honest, sober and industrious," prospered in a welcoming land of opportunity which gave him choice of occupation and residence.”

Not all were in agreement with de Crèvecoeur, with Benjamin Franklin being the best known opponent of his definition:

Benjamin Franklin believed the English and the Saxons provided “the principal body of white people” in the world. Franklin felt some white identity, but he excluded most non-English from its bounds, fearing that “swarthy” immigrants would “Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them” since they would “never adopt our language or customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion.” Other writers spoke confidently of assimilation, though some, such as J. Hector St. Jean de Crèvecoeur, imagined the “strange mixture of blood” among a “promiscuous breed” of Europeans creating “a new race of men.”

There is no possible doubt that de Crèvecoeur was predicting the formation of a new ethnos. To be fair, being a naturalized US citizen of ethnic French stock, his more liberal definition of what constituted an American was rather self-serving.