The Spanish Civil War in Retrospect: Why Did Spaniards Rebel Against Their Government?

It is impossible to understand the 20th century without understanding this conflict, one that continues to resonate to this day

Author’s Note:

I was recently asked to write about the Spanish Civil War and why people turned against the Republican regime and sided with Francisco Franco and other military figures who attempted to launch a coup d'état to overthrow the government in July of 1936. This essay will attempt to answer this question by painting a broad portrait of the events that lead up to that bloody conflict. This will not be a comprehensive treatment of the subject of what led Spain to fall apart that summer, as it will mainly focus on the interests, concerns, and arguments of one side (which contained many different factions, often at odds with one another). Therefore, it will not be an objective look, and will instead be very partial to one side in order to answer the question that was posed to me. A lot of obvious (and less well-known) facts will be missing from this piece due to the constraints put on it by the question I intend to answer, and for the sake of brevity.

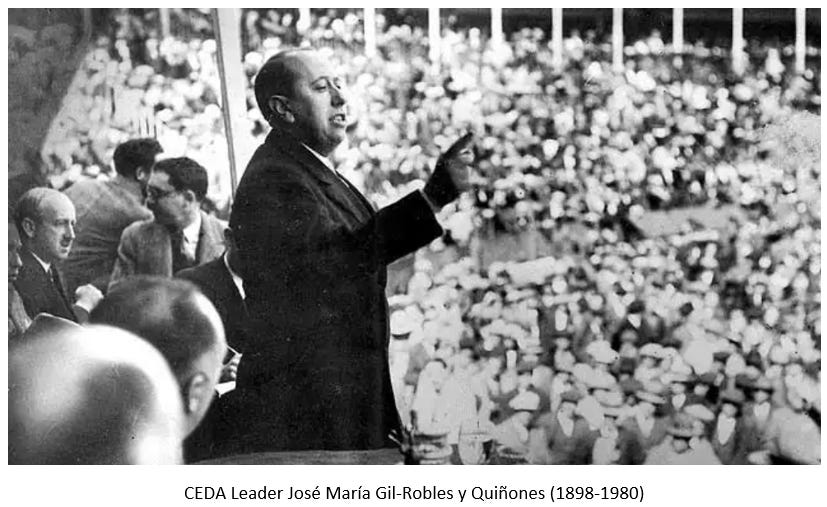

If this essay generates enough interest, I will happily continue the story, beginning with the conservatives forming a government led by Gil Robles and CEDA…but this is entirely up to you.

“Don Ricardo was a short man with gray hair and a thick neck and he had a shirt on with no collar. He was bow-legged from much horseback riding. ‘Good-by,’ he said to all those who were kneeling. ‘Don’t be sad. To die is nothing. The only bad thing is to die at the hands of this canalla. Don’t touch me,’ he said to Pablo. ‘Don’t touch me with your shotgun.’

“He walked out of the front of the Ayuntamiento with his gray hair and his small gray eyes and his thick neck looking very short and angry. He looked at the double line of peasants and he spat on the ground. He could spit actual saliva which, in such a circumstance, as you should know, Inglés, is very rare and he said, ‘Arriba Espana! Down with the miscalled Republic and I obscenity in the milk of your fathers.’

“So they clubbed him to death very quickly because of the insult, beating him as soon as he reached the first of the men, beating him as he tried to walk with his head up, beating him until he fell and chopping at him with reaping hooks and the sickles, and many men bore him to the edge of the cliff to throw him over and there was blood now on their hands and on their clothing, and now began to be the feeling that these who came out were truly enemies and should be killed.

From Ernest Hemingway’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls”

The above excerpt is a piece of historical fiction courtesy of American author and legend, Ernest Hemingway. At a crossroads in his life, he decided to go to Spain to cover the conflict for a newspaper chain. Out of his experiences in that war came “For Whom the Bell Tolls” (1940), one of his most celebrated novels. In this excerpt, he uses the female character ‘Pilar’ to relate the story of how Republican forces massacred a group of people in a small town who were opposed to the government and supported the Spanish Generals seeking to overthrow it. Derided as “fascists”, each of the men were forced to pass a line of pro-government peasants who would beat them with flails before throwing them off of a cliff. Civil wars are indeed the most vicious, even in fictional depictions like this one.

The Spanish Civil War is odd for two reasons, the first one being that more than any other war that I can think of, historians have placed a much stronger focus on the politics of the conflict to the detriment of its military aspects. The second reason is much more important overall, and particularly germane to the subject of this essay: it is the only war that I can think of where the histories have been overwhelmingly written by the losers.1

If you ask a random, somewhat educated person in the West about the Spanish Civil War, they will generally say that “Franco was a fascist who allied himself to Hitler and Mussolini and won the civil war in the most brutal fashion possible. He was a dictator who hated democracy and killed thousands upon thousands of innocent people.” Beyond that, they might make mention of Hemingway and his novel, or even Pablo Picasso’s painting entitled “Guernica”2, that depicts the victims of the German Luftwaffe bombardment of that small Basque town in the north of Spain. Others still will relay the fact that the term “Fifth Column” came out of the Spanish Civil War.3 Added up all together, the most simplified take becomes “Franco bad, Republicans good”.

Of course this take is wrong, as this conflict was too complex to arrive at such a ridiculous reductionist conclusion no matter which side you sympathize(d) with. To give you a quick illustration of just how complex this conflict was, here is a list of the major domestic factions that took part in it:

Spanish Republican Side:

People’s Army (the armed forces of the Spanish Republic)

Popular Front (left-wing electoral alliance of communists, socialists, liberals, anarchists)

UGT (very large trade union affiliated with the Spanish Socialists)

CNT-FAI (massive trade union of anarchist militants)

POUM (anti-Stalinist communists, including some Trotskyites)4

Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalonian Autonomists)

Euzko Gudarostea (Army of the Basque Nationalists)

Spanish Nationalist Side:

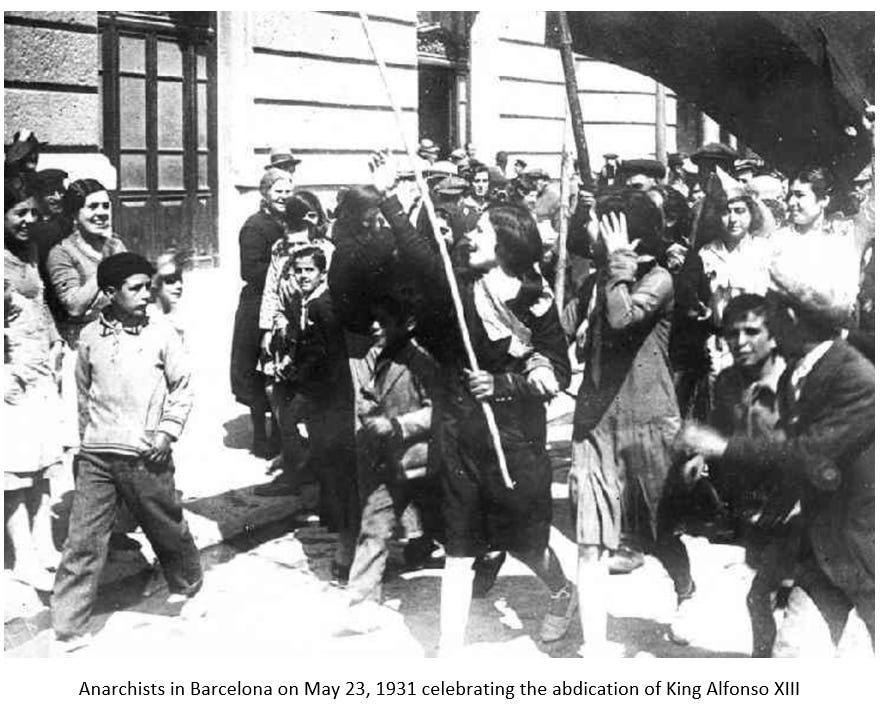

Spanish Renovation (monarchists supporting the Bourbon claimant to the throne, Alfonso XIII, who abdicated in 1931)

CEDA (the main conservative party, Catholic conservatives)

Requetés (traditionalist Catholic monarchist militants who supported the Carlist Dynasty, mainly from the region of Navarre)

Falange Española de las JONS (Spanish Fascists)

The Army of Africa, including the Spanish Legion (Spanish Army in Spain’s then-colony of Morocco, with many Moroccans serving in it)

Add to this mix the International Brigades5 that fought on the side of the government, and the German and Italian forces who backed the rebels. To list off all the political groupings that participated in the war is a mouthful, but necessary to hammer home the point of the complexity of this conflict. So here goes: nationalists, monarchists (from two competing royal houses), fascists, conservatives, liberals, social democrats, socialists, communists (from two competing camps), anarchists, and regional autonomists. In short, this war had something for everyone, which is why it caught the attention of so many foreigners (especially famous ones) at the time. But before we dive into the run up to the civil war, we need to understand some of the history of Spain that lead up to this “world war in miniature”.

A Very, Very Brief History of Modern Spain Up Until the Establishment of the Second Spanish Republic

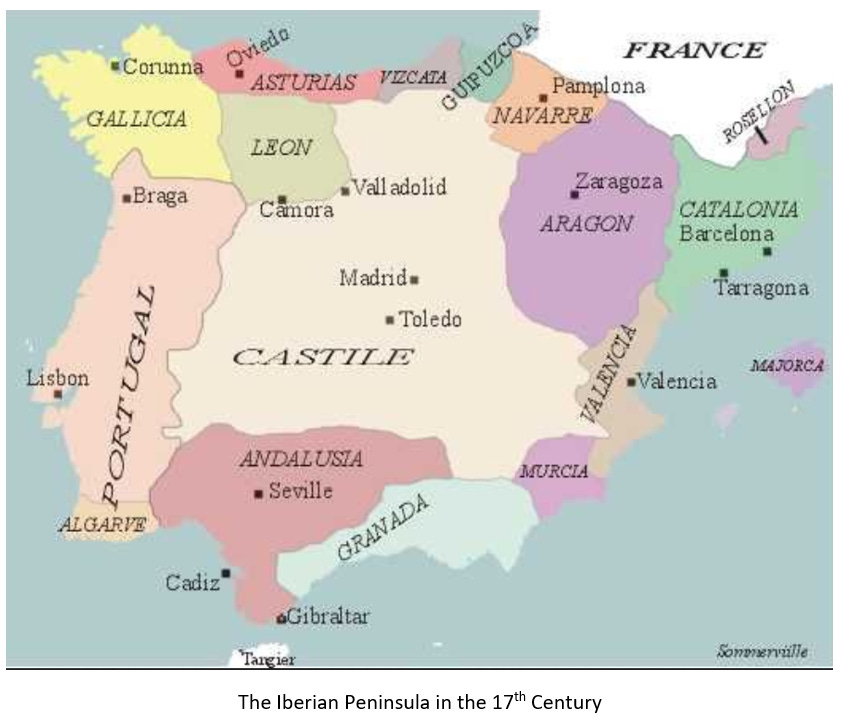

Together with Portugal, the Spanish Empire led the world in the exploration of the globe and its colonization, opening up trade routes across oceans to exploit the natural wealth that they found in these new lands. Silver came first, and then gold. This propelled Spain to be the world’s foremost power in the 16th century, ruling the waves until its Armada was defeated by the English in 1588. Despite expanding in the 18th century, the Spanish Empire was already in decline by the mid 17th century, as the French, English/British, and Dutch overtook them diplomatically, militarily and technologically.

The 17th century was marked by economic stagnation and decline, as inflation, heavy taxation and mismanagement of the economy (including repeated plundering of the royal treasury by the nobility) were rampant, leading many Spaniards to emigrate to the colonies in the New World. Some parts of Spain even began to deindustrialize during this era, compounding its woes.

By the early 18th century, a Spanish nation-state began to emerge as Castile began to exert its dominance over the Iberian Peninsula, and the various non-Castilian peoples on it like the Aragonese, Galicians, Basques, and Catalonians. Castile would form the core of Modern Spain, a condition that prevails to this day.6

In 1715, the Wars of the Spanish Succession ended with a Bourbon victory over the Habsburgs, transferring control of Spain and its empire to the victors. Despite some reforms that improved the economy, empire, aristocracy, and the Church were still its main concerns, with The Enlightenment (that was spreading across much of Europe at that time) almost completely passing it by. Spain became involved in the tug-of-war between Britain and France over the next century, ending in disaster during the Peninsular War when erstwhile ally Napoleon occupied Spain, leading to a bloody rebellion that economically devastated it. It also sparked a series of rebellions in its colonies in North and South America, resulting in the loss of possession of all of them (except Cuba and Puerto Rico) by 1826. With the loss of those colonies, Spain’s international presence, importance, and prestige were significantly eroded.

A much reduced Spain was firmly in the hands of the nobles and the Church, with a large landowning aristocracy, and a very large peasant class that either owned tiny plots of land to cultivate, or no land whatsoever. A middle class did began to grow in size in urban settings, providing a new addition to the social dynamic during that period. But the devastation wrought by the French occupation (and the rebellion against it) combined with the loss of its colonies impoverished the Spanish Kingdom. Outside of Catalonia, industrialization was absent. The exploitation of natural resources like coal were hampered by a primitive transportation system. Demographic decline set in with massive emigration to former colonies in the Americas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1812, a very liberal constitution (the Constitution of Cadiz) was adopted by the Spanish royals. Despite its formal adoption, significant resistance to it from Ferdinand VII and his conservative allies made it little more than a piece of toilet paper, at least to them. It was this fight between liberals and absolutists that would colour the rest of 19th century Spain, one dominated by conspiracies, palace intrigues, coups, and military interventions. So riven was Spain by factionalism between parties and within parties that Amadeus of Savoy, elected to be its King Amadeo I, famously concluded that the Spanish people were ungovernable. He immediately abdicated the throne and left the country for good.

Amadeus’ flight into exile created a political vacuum, one that was quickly filled by radicals and Republicans who declared the First Spanish Republic. This initial foray into republicanism ended in a little over a year due to the immense opposition it encountered from monarchists, the Catholic Church, and military figures who launched a successful coup that restored the Bourbons to the throne. This republic also saw regional unrest and rebellions in Catalonia and Navarre, and just as significantly, it also was witness to pro-republican socialists demanding revolution i.e. redistribution of land.

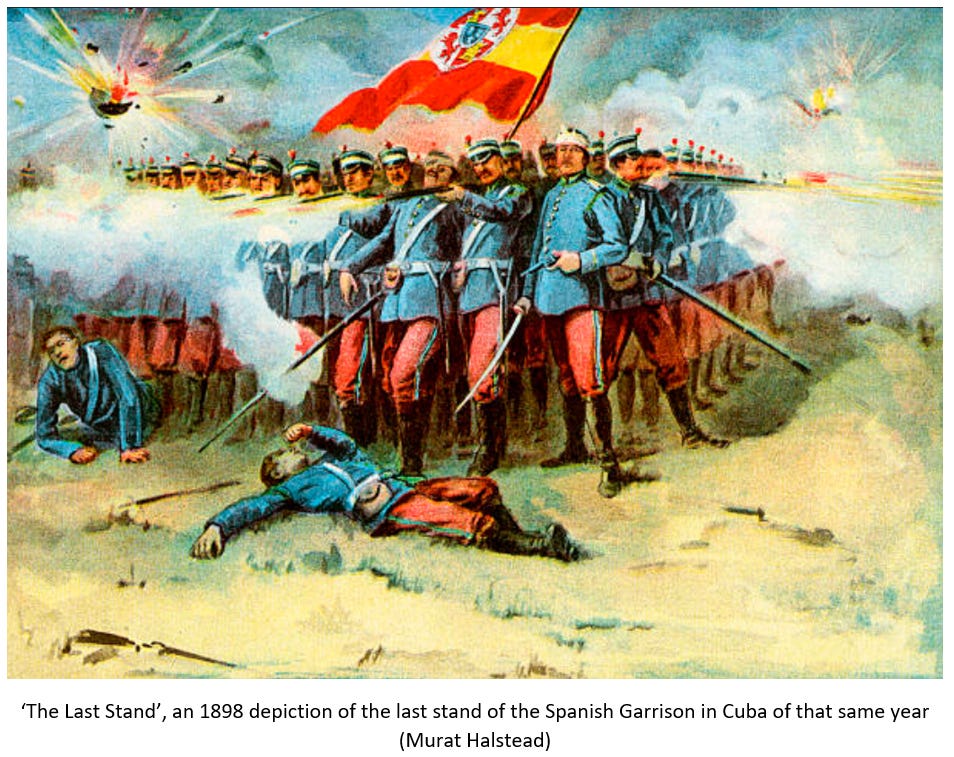

In 1898, Spain experienced a “disaster”; the loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and The Philippines to the USA in the Spanish-American War. The so-called Spanish Empire was reduced to colonial holdings in Morocco, the Sahara, and Guinea. It had finally been evicted from the Americas and the Pacific as well. This resulted in a turn towards liberalism from intellectuals and politicians who felt that Spain’s anachronistic system was hopelessly uncompetitive against its modernizing rivals. On the other hand, Geoffrey Jensen argues that it was this catastrophic defeat that led the once relatively liberal military officer class to turn to the right.7

Even though Spain avoided the First World War and actually economically profited from it, the regime was still very unstable due to regional nationalism, widespread poverty, and severe political factionalism that paralyzed the state. The coup de grace was delivered by another military disaster: a serious defeat of the Spanish Army in Northern Africa at the hands of Berber tribesmen in 1921 at the beginning of the Rif War. 9,000 Spanish soldiers were killed or executed in this catastrophe in a matter of days, shaking Spain to its core.

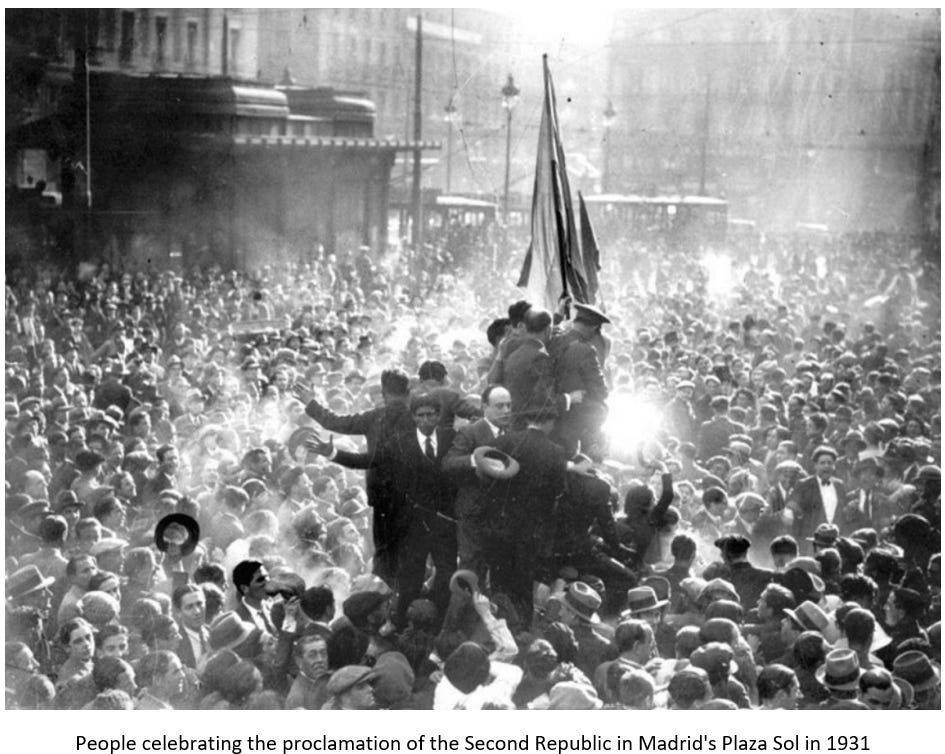

King Alfonso XIII gave his secret backing to yet another military coup that resulted in a dictatorship under Miguel Primo de Rivera, lasting from 1923 until 1930. During this period, Spain ended the rebellion in the Rif thanks to aid from France. Economic conditions improved over the course of the decade, but the arrival of the Great Depression quickly erased all those gains, leading to a collapse in support for both Primo de Rivera and Alfonso XIII. The king removed the dictator from power, but this action only bought him a short window of time, as he had already lost the support of the urban masses of the lower and middle classes. In April of 1931, local elections proved to be a plebiscite on the Spanish Monarchy, with republican parties overwhelmingly winning the vote. Alfonso XIII read the writing on the wall, abdicated his throne, and headed into exile.

The Second Spanish Republic

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

-William Butler Yeats “The Second Coming” (1919)

This was finally it! The moment that millions of Spaniards had been waiting for had finally arrived! Shorn of its ‘regressive’ Monarchy, Spain and its citizens could finally enter modernity with pride and say goodbye to its backward past once and for all. Liberalism had finally won and Spain could now look to the future with an optimism so sunny that even an Andalusian summer would envy. Poverty and illiteracy would be eliminated, reason would replace superstition, and land would be redistributed to the poor.

Most of you reading this essay are American, and many of you are not familiar with this slice of history. When you see, read, or hear the word “republicanism”, you will naturally mentally associate it with your country’s version of it. Us non-Americans are very used to Americans informing us that the USA “is not a democracy, but is instead a constitutional republic”. I do like to mention from time to time that I have always admired how civics lessons were drilled into the heads of American students from a very young age. In your minds, republicanism is not a negative concept, and you would be right to view it that way considering just how stable and successful your country has been serviced by this system of governance.

Not all republics are created equal, nor do they all perform at an equal level. The First Spanish Republic ended in less than two years thanks to enormous resistance and a military coup that overthrew it. The Second Spanish Republic lasted eight years, with a military coup that attempted to overthrow it five years into its existence, failing to do so, resulting in a horrible, tragic, and bloody civil war. The story of the Second Spanish Republic is the story of a centre that could not hold, with powerful and passionate forces far from its centre pulling in totally opposite directions, tearing the country into two pieces.

“A republic, if you can keep it”

In the first election for the Spanish Cortes (parliament) since the proclamation of the Second Republic, the Spanish right was in disarray and wholly unorganized due to the shock of Alfonso XIII’s abdication. With little options for an alternative to the new state of affairs, conservatives and right wingers largely threw their lots in with the Radical Republican Party, as its platform was viewed to be the least damaging to their interests. Others backed the Liberal Republican Right (DLR) as it openly defined itself as Catholic, the only major party to do so in this campaign.

The Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) fared the best overall, urging a “legal revolution” to resolve Spain’s economic and social ills. Despite this pledge to uphold legality, the party contained many extremist factions who sought to either use incrementalism to usher in a socialist state, or radicalism to do it quickly. These radicals were almost a carbon copy of the Radical Socialist Party (PRRS), a grouping who sought immediate socialist revolution for Spain, as “there is nothing to be conserved”.8

These Republicans and Socialists were in an electoral coalition, allowing them to win the elections handily. Now it was time for them to govern.

Covering the centre-right, bourgeois left, and socialists, Spain’s first republican government found itself to be swimming against the anti-democratic tide sweeping Europe. Democracy was seen as not capable to solve the many, many debilitating issues caused by the Great Depression, with authoritarianism of the left or right viewed as better suited to tackle them. The fact of the matter is that this democratic system did work to impede many of the reforms sought by the coalition government, and by millions of Spaniards as well. Paralysis in government, caused at first by unwieldly governing coalitions, and then by unrest, strikes, and violent rebellions, led many who were initially enthusiastic about the democratic aspects of republicanism to quickly conclude that the democracy part should be done away with.

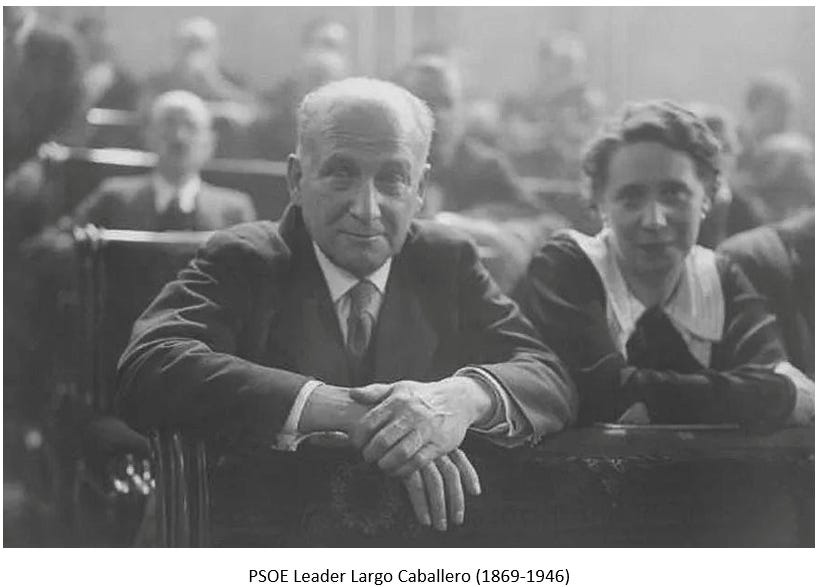

Stanley Payne describes for us the Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), the party that captured the most votes:

The Republican left formed only the left-center of the new governing alliance, whose left wing was the Socialist Party. Founded in 1879, the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) was a classic movement of the Second International that for decades had been one of the weakest Socialist parties in Europe.

……..

Always treated leniently by the Spanish government, the Socialists had on most occasions followed more moderate policies, participating in elections and slowly building a trade union base. The profound structural changes of the 1920s and the coming of democracy enabled the Socialist trade union, the Unión General de Trabajadores (General Union of Workers; UGT), to expand into a mass movement, reaching more than a million members by 1932. The Second Republic offered the Socialists their first opportunity to participate in a government — something that the French Socialists had not yet done — an opportunity that they accepted without having fully resolved the issues of reformism versus revolutionism in their doctrine. The dominant tendency was to take the position that the Republic would produce decisive changes, opening the way peacefully for a Socialist system to be achieved without revolutionary violence. The UGT leader Francisco Largo Caballero declared at the outset of the new regime that as a result violent revolution “would never put down roots in Spain.” The Socialists also viewed the Spanish changes within a larger context as a new tide of democracy and progressivism that would roll back the trend toward fascism initiated by Mussolini a decade earlier.9

At first they were dedicated to constitutional legalism, but much of the party began to radicalize very quickly, especially Largo Caballero. Almost immediately, the Socialists clashed with the Radical Republicans over the question of private property, with the Socialists seeking to expropriate land from wealthy landowners to redistribute to campesinos. This led to the departure of the Radical Republicans from government with its remaining coalition partners.

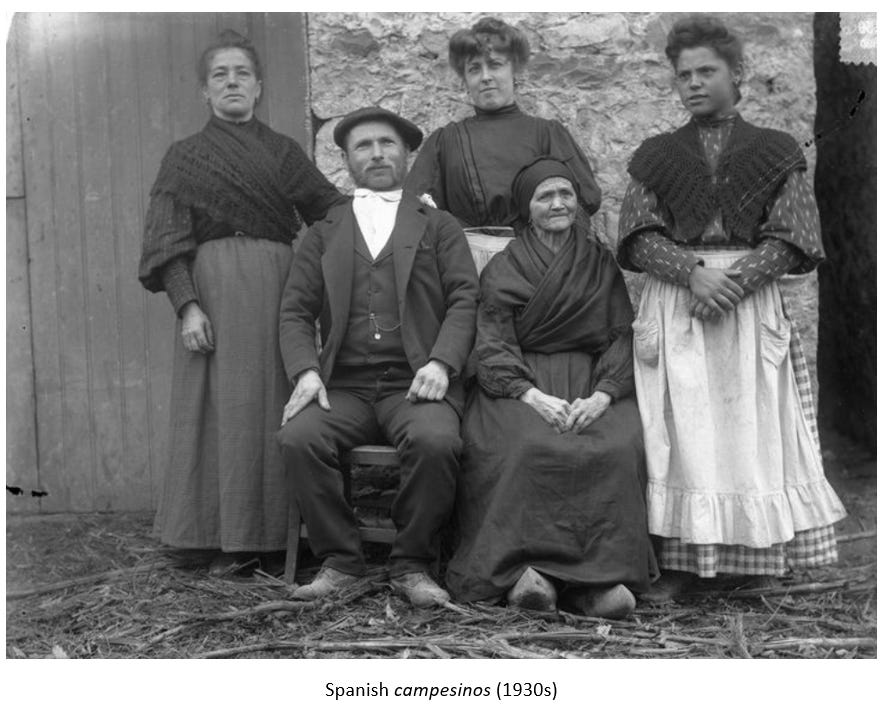

The Agrarian Question

The “Agrarian Question” was one of the key issues that Spain faced for some time. In 1931, some two million Spaniards were landless peasants, forced to work on the big latifundia estates owned by incredibly rich landlords who paid them a pittance to farm their holdings. This issue was highly divisive, as it pitted the wealthy landowning aristocracy and its allies in the Catholic Church against a very large and dirt poor mass that was already politically radicalized, with most supporting anarchism as the best political option to pursue their interests. These anarchists, mainly found in Catalonia, Aragon, and Andalusia, were radicalizing even further, as physical violence was seen as an acceptable tool to seize land from these rich landowners. The campesinos were impatient and demanded land redistribution immediately, “or else”. Furthermore, the various parties supporting republicanism made land redistribution a core issue of their platform. They had to deliver on their promises.

Land redistribution implies forceful seizure of property by government, a very radical act. The emphasis on this issue put the fear of God into many landowners, and into other holders of private property (especially industrialists) as they feared that they would be the next target.

Anti-Clericalism and Anti-Catholicism

“In Spain, Priests are followed by a person holding a candle….or a knife”

More than any state repression, more than any economic exploitation, the republican government viewed the Catholic Church as its primary enemy. The Church was a roadblock in the drive to modernize Spain, and its complete removal from the public square and the destruction of its influence on Spanish society were viewed as the most necessary tasks at hand by the new government. In fact, this all served as the lowest common denominator for the ruling parties. It was where there was the most overlap, the lowest-hanging fruit for agreement.

Radical secularism was the path forward, and, as Payne notes, it began to eerily mirror all the criticism it levelled against the Church and its Priesthood. It took on a fanatical tenor, to the point of resembling medieval religious fervour. Everything wrong with Spain was to be blamed on the Church.

As Payne writes:

The more radical secular ideologies themselves functioned, if not as “political religions,” at least in many cases as politico-ideological substitutes for religion. Only as a kind of religious warfare can the intensity of the clerical-anticlerical conflict in Spain be understood. Much of anticlerical doctrine came from France, and condemned Catholicism for every manner of ills: excessive possession of wealth of various kinds, oppression of the poor, maintaining an authoritarian internal structure, a supposedly overweening political influence, preaching political doctrines in church, sexual abuse and perversion, chaining the common people to ignorance and poverty. The Church was also blamed for historical abuses and the failures of Spain and of its empire.

The anticlericals seemed to present a mirror image of what they denounced, exhibiting extreme intolerance and desire for domination, which might be expected to stimulate an equivalent response in Catholics. Anticlericalism also showed a pronounced tendency to replace the sacrificial and liturgical role of the Church, inverting the Passion of Christ in anticlerical rituals, while the worker left advanced its own concepts of the sacrificial, redemptive role of the common people.10

Laws were passed to deny clergy the right to teach children in the name of ‘public health’.

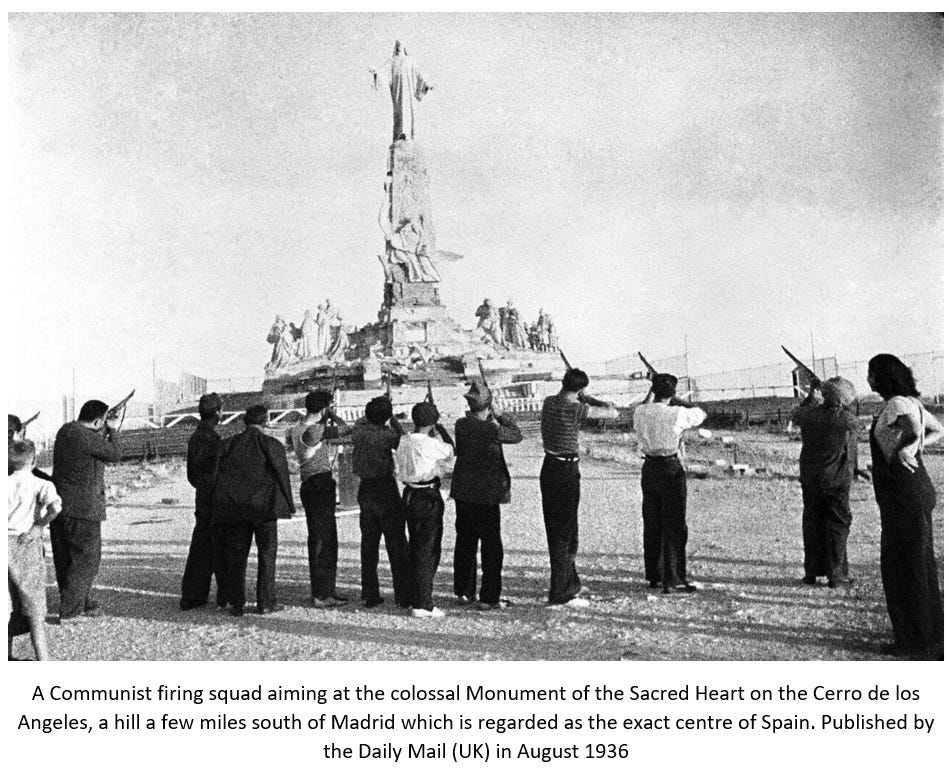

And then came the violence, years before the actual civil war:

Certain other restrictions were placed on Church economic activity, and public demonstrations of religion were also banned. The Society of Jesus was dissolved, priests were occasionally fined for delivering “political sermons,” and some of the more zealous city councils even fined Catholic women for wearing crosses around their necks. Very early in the life of the new government, Catholic churches and buildings became targets of arson and mob destruction in the famous quema de conventos of 11 – 12 May 1931, in which more than 100 buildings were torched and sacked in Madrid and several cities of the south and east, destroying also priceless libraries and art. The authorities then gave the first example of the left Republican habit of “blaming the victim” by acting to arrest monarchists and conservatives rather than the authors of the destruction. Later, during the spring of 1936, illegal seizures of Church buildings and properties would often simply be winked at by the Azaña – Casares Quiroga governments then in power. At no time did any of the leftist parties take the position that Church interests and properties merited the full protection of a state of law.11

The government did nothing to stop the evictions of Priests and Nuns from their churches and convents, nor did they try to stop the looting and torching of these same buildings. They were given carte blanche by ruling authorities to forcibly secularize Spain via these acts of violence. Manuel Azaña, then Minister of War in the cabinet (he would go on to become Prime Minister of Spain later that year, and then President of the Republic from 1936-1939), famously proclaimed “All the convents in Spain are not worth a single Republican life”.12 He led the left-liberal republican party Republican Action (AR). To him, it was critical that the Catholic Church be denied any role in education in Spain. Furthermore, civil marriage was to be instituted in place of the Catholic Sacrament, all church property was to be seized, and lastly the Jesuit Order was to be expelled from the country altogether. In Republican Spain, he was slightly to the left of centre.

The first government managed to pass a law on land expropriation, but very little was taken out of the hands of landowners, and none of them were the largest ones. The only ones who experienced land seizures were smaller and medium-sized landowners. The only real successes that they scored were in some labour reforms like the introduction of collective bargaining rights13 and the extension of the vote to all adult women. Besides barring Catholic Orders from education, divorce was legalized, nobles were stripped of their titles, and the new Constitution enshrined the right of local autonomy for Spain’s regions.

Early Challengers to the Government and the Republican System

Counterintuitively, the first challengers to the new regime appear not from the recently-defeated right, but rather from the left…the hard left.

Spain was unique in that it had a strong anarchist, specifically anarcho-syndicalist, tradition, unlike elsewhere in Europe where the far left was dominated by Bolsheviks, and later, Stalinists. This was due to certain idiosyncrasies belonging to Spain, such a traditionally weak central state combined with localism, and the lack of the development of a large industrial proletariat (which didn’t arrive until much, much later).

The anarchists were fanatically anti-Catholic, much more radical than even the communists, and were the main source of political violence in the first 1/3rd of 20th century Spain. They were THE dangerous extremists.

Their labour union, CNT, boasted up to two million members, and FAI served as their political vanguard. Together they launched three violent insurrections against the republican regime, with all three failing and the result being increased repression of the CNT. The Anarchists were a mass movement with widespread support, strongest both in rural Andalusia and industrial Barcelona.

OTOH, the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) was rather lacking. Entirely directed from Moscow, their party base was miniscule up until 1936. Only then would they begin to take a prominent role in Spanish politics…a very, very prominent one!

The overt Anti-Catholic laws and the violence directed against Catholics and their churches naturally caused the rise of Catholic reaction. Carlists began to train paramilitary forces in the province of Navarre. Other monarchists began to openly call for the return of the monarchy under a centralist and authoritarian regime of their own.

The only insurrection from the right came courtesy of a weak and failed pronunciamento courtesy of General Sanjurjo, and a select cadre of officers in Madrid and Seville.

Only in Seville did the revolt succeed for a few hours, the retired General José Sanjurjo briefly seizing control of the garrison and city before he was forced to flee. This revolt was even weaker than any of the anarchist insurrections and was easily suppressed. Ten people were killed. Sanjurjo was quickly arrested, tried, and sentenced to a long prison term.14

The republican regime responded to these challenges by repression. The press was clamped down so hard that Italian dictator Benito Mussolini congratulated Azaña for his ‘decisive action’. The government passed the ‘Law of the Defense of the Republic’ which led to the creation of the Assault Guards, a police force that acted quickly and brutally to any perceived threats to the constitutional regime.

Mindful of complaints that the special national constabulary, the Civil Guard, was armed only with Mauser rifles and not trained for modern crowd control, the Republican authorities set about organizing a new urban constabulary armed with clubs and pistols, theoretically prepared for more humane crowd control. Its very name, Guardias de Asalto, indicated the vigorous policy espoused by the Republican regime. Incidents proliferated as strikes, demonstrations, and insurrections produced considerable violence, which in turn prompted harsh repression from the Civil Guard and the Assault Guard. After two and a half years, there had been nearly 500 fatalities in such confrontations, the majority of the victims being anarchosyndicalists, and suspension of civil guarantees had become more frequent than under the constitutional monarchy before 1923.15

This government radicalism also threw up the most important challenger, CEDA, a mass political movement of the Catholic right. Even though it had a stated policy of legality and parliamentarianism, it sought to capture the republic in order to create its own non-liberal society, much like how the PSOE sought to use legalism to create a socialist Spain. Its rapid rise was both a reaction to the state’s overt anti-Catholicism and anti-traditionalism, and a result of the right beginning to organize after two years in the political wilderness.

The Casas Viejas Incident

The historical consensus is that the Second Spanish Republic began to break down in 1934 courtesy of that year’s insurrection (which we will deal with next week), but Payne insists that instead the process began with the Casas Viejas Incident (January, 1933).

In the classic Thames Television documentary series “The World at War” (UK, 1970s), a German Social-Democrat who sat in the Reichstag in the Weimar Era explains how The Night of the Long Knives ended any ambiguity about the Nazis as they went from having a chance in governance to being outright murderers. This view stuck with me over the years and I was reminded of it when first learning about the Casas Viejas Incident years ago.

Staying true to form, the anarchists were restless and, as is their nature, opposed the present government in Spain as they opposed all governments, viewing them as inherently oppressive. Their massive labour union, CNT, led by the vanguard of FAI, began demonstrations in various locations across the country, with the greatest actions taking place in Andalusia. Political violence ensued, with two Civil Guards wounded. The Assault Guards, set up by the new Constitutional authorities in the Republic to provide a new force to purportedly protect those who lacked protection under the Monarchy, raided the village of Casas Viejas near Cadiz. They encountered a group of anarchists locked in a house and set fire to it (while disarming others in the village who were armed), and then executed them.

At this point the Second Spanish Republic was already a ‘murderer’.

A Teetering Government

By this point, the central conflict was between the competing visions of the republican parties (albeit divided among themselves) and the Socialists who paid lip service to republicanism, merely seeking to use it to create a socialist state. The Youth wing of the PSOE was even more radical than the main party as it sought to completely move away from parliamentary democracy towards the immediate creation of the a socialist state.

Even though the Socialists sought radical change, they were outflanked by the much more radical anarchists organized around their labour union, CNT. They managed to wrest even greater labour concessions out of the government via demonstrations, strikes, and violent acts than the Socialists did by way of legislation. Socialist collaboration in reform legislation only led to greater labour unrest as the CNT outflanked the UGT (Socialist trade union organization) by direct action. Extra-legislative actions gained more for certain groups than did the legislative process. This lesson was taken to heart by the anarchists who viewed it as a win for their political philosophy, and served as a loss for the constitutional order.

Warning Against Radicalization

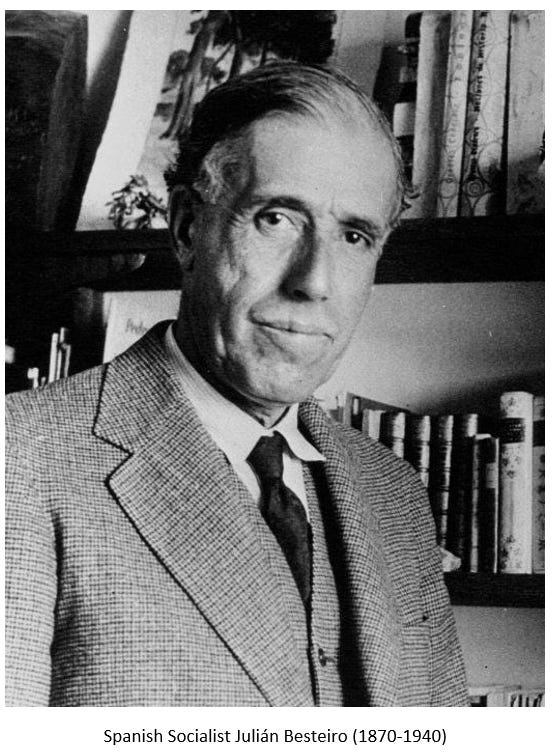

Much as there are many people sounding the alarm about the increasing political polarization in the USA, 1930s Spain had its own faces that did the exact same thing. Spanish Socialist Julián Besteiro was one of those faces, and he took the opportunity of speaking before a gathering of Socialist Youth to warn them about the dangers of opening Pandora’s Box:

In July he had blamed Italian and German Socialists for provoking the bourgeoisie of their countries into fascism through the premature use of Socialist power, even though in Germany this had taken the form of parliamentary government participation. Worse yet, the introduction of a Socialist regime in Spain through Bolshevik-style violence and dictatorship would simply inaugurate a bloodbath, “the most sanguinary Republic known to contemporary history.” Besteiro’s Cassandra-like predictions were uncannily accurate, and this was no exception: in the Republican Zone during the first six months of the Civil War in 1936, the rate of political executions would considerably exceed that of the Bolsheviks during the Russian civil war. At Torrelodones he once more warned of the folly of extremism, the results of which would be quite di¤erent from what its advocates imagined: “If a general staff dispatches its army to fight in unfavorable conditions, it becomes totally responsible for the subsequent defeat and demoralization,” adding that “often it is more revolutionary to resist collective madness than to be carried away by it.”16

Powerful Spanish Socialist Indalecio Prieto warned his more extreme youthful comrades not to engage in the same methodology:

Prieto was less challenging but also warned that there were definite limits to what Spanish Socialism could achieve at the present level of development and given the changing relations of political forces both in Europe and in Spain. He too stressed the fallacy of the facile comparisons being made by the left wing of the movement between Russia in 1917 and Spain in 1933. In Russia key institutions had already collapsed before the Communist takeover; in Spain the government, Church, and armed forces were intact, while the bourgeoisie was stronger than in Russia.17

The Socialists continued to radicalize, despite these warnings, leading to the various republican parties in the governing coalition finally breaking with them, and calling for a new election.

The End of the Coalition Government

When one skims through history, our western liberal bias leads our brains to automatically assume that a democracy would somehow be more inherently moderate than a dictatorship, whether military or monarchical, or whatever. The Second Spanish Republic quickly disabuses us of this notion:

As Ángel Alcalá Galve observes, one of the striking features of the new regime was the manner in which it quickly reproduced key weaknesses of the old monarchist system, demonstrating that the problem was not really one of monarchy versus Republic but of the Spanish political culture of the early twentieth century, which was proving intractable.18

What this means is that regardless of the form of governance that is adopted, deeper conflicts are at play and it is not the system that is responsible for it. There is a fatalism in this in that some conflicts do have to play themselves out until one side wins and the other loses, or both sides exhaust themselves and arrange a consensus, or a third power removes the first two.

History repeating itself:

Whereas the old system had been threatened by an extreme left, the new system was threatened with subversion and violence by both an extreme right and an extreme left. Just as the monarchist parties had become too internally divided to govern, this internal division now threatened the Republican parties. The Socialists had attempted a revolutionary general strike against the monarchy in 1917; in 1934 they would attempt one against the Republic.19

A new system can allow for new representations and can create new forms of governance, but it is not necessarily a silver bullet for deeper-seated problems.

Now watch this part and think of the current struggles between liberals and those exact liberals disenchanted with what we call “The Woke” today:

The middle classes were fragmenting into a Catholic right, a liberal center, and a Republican left……Eventually the gulf between liberal and left Republicans would become unbridgeable. The increasing split in the Republican parties, with only the liberals willing to accept the logic and rules of a liberal democratic system, placed the future of the new regime in doubt. If all the Republican parties did not accept their own system, there was even less to expect from the non-Republican parties.20

Many liberals, of which I include today’s American conservatives and Classic Liberals, insist on appealing to reason and principle, while the hard left runs them over with the application of sheer power. Here is Popper’s “Paradox of Tolerance” but repositioned: should liberals tolerate those from the left that do not tolerate liberalism?

The Elections of November 1933

1931-33 served as little more than a leftist convention in government; conservatives and the right did not put up a fight against republicanism as they sat on the sidelines while the left rammed through a series of reforms that alienated the former. Yet the internal disputes between the various republican parties and the PSOE led to the collapse of the government and the need to call new elections.

The left sought to sandbag their first electoral win by changing the rules so as to allow them to capture more seats in a mixed first-past-the-post and proportional system that favoured large parties to the detriment of smaller ones. What they didn’t bank on was opposition to their rule manifesting itself in an electoral loss.

A violent campaign (this time with the Socialists playing a leading role, and with church burnings making a comeback) saw two ceditas (from the CEDA party) murdered, courtesy of a small republican party out of Valencia. The temperature was high and rising.

Nevertheless, CEDA managed to score 115 seats, with the Radical Republicans 104, and the PSOE only 60, in a system that was supposed to be tilted to the left. They had shot themselves in the foot and immediately cried foul. The granting of the franchise to women served to help CEDA, and Spain’s democratic centre was now strengthened. The left immediately sought to overturn the results of this vote, with various bizarre schemes that all fizzled out. They openly used the arguments that were made against their electoral reforms by the opposition to argue in favour of overturning their loss!

BTW, does this sound familiar?

This whole dismal maneuver revealed what had become the permanent position of the left under the Republic: they would accept only the permanent government of the left. Any election or government not dominated by the left was neither “Republican” nor “democratic,” a position that might well have the effect of making a democratic Republic impossible.

……….

When even its own tendentious and unfair regulations were inadequate to give it electoral victory in 1933, the left chose to ignore the very constitution it had been instrumental in writing. From this time forward, the left would flout legality ever more systematically, eventually reducing the legal order to shambles and setting the stage for civil war.21

A conservative reaction to the first two years of rule by republicans and socialists resulted in an electoral victory. What would they choose to do while in power? In the meantime, the anarchists were up to their old tricks again.

Anarcho-Syndicalist Insurrection of December 1933

Once again, the Anarchists were back at it and this time they had much more success than at the beginning of the same year.

Bombs went off in Barcelona, trains were derailed elsewhere, an armed revolt took place in Badajoz in the southeast of the country. Barcelona and Zaragoza saw the brunt of the action, and FAI-CNT took over towns in Huesca, Alava, and Logroñ, declaring ‘libertarian communism’, torching money and records during their short-lived rule. The Civil Guards once again quickly put down the revolt.

This was the sixth(!) violent insurrection in 3 years. The net effect was the continuing suspension of civil rights and the destruction of faith in the new constitutional order.

Concluding Remarks

This is the perfect time in this story to stop for now. The conservatives are about to form a government for the first time in the Spanish Republic, and will face immense opposition, both legal and extralegal.

The pace of the division and collapse of Spain begins to really pick up from this point onwards, as leftist factions simply refuse to not tolerate being in control of the country. Violence begins to soar as faith in the governing system and its institutions erodes rapidly. Extreme political, social, and cultural polarization sets in as the centre significantly shrinks, with compromise between parties all but impossible. Meanwhile, the officer class watches events unfold closely, and with serious concern as to how they are developing.

If you enjoyed this introduction to this subject and want me to continue, I ask you kindly to click this button below to support my writing. A lot of work goes into these essays, and a lot of time is spent researching and writing as well. The Spanish Civil War is one of my favourite historical subjects due to its significance and also because of how it resonates to this day. Hit the button below and support my work:

And feel free to leave a comment below:

Lastly, feel free to share this essay with others and on social media:

Check This Out!

Jack Posobiec and Blake Neff recently released a podcast special on this exact same topic.

Click this link to give it a listen

"History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it" - falsely attributed to Winston Churchill, but it makes for a good quote to illustrate the point. From the International Churchill Society: “‘Alas poor Baldwin. History will be unkind to him. For I will write that history.’ And another version often repeated is ‘History will be kind to me. For I intend to write it.’

What Churchill actually said, in the House of Commons in January 1948, was in response to a speech by Herbert Morrison, the Labour Lord Privy Seal, which attacked the Conservatives’ foreign policy before the war:

“For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.”

In January of 1937, Picasso was commissioned by the Spanish Republican government to create a work of art to display at the upcoming World’s Fair in Paris in order to draw international attention to their cause. At the time, Picasso was living in the French capital. It wasn’t until he read reports of the bombing of Guernica on April 26 of that same year that he felt inspired enough to create something that he felt was worthwhile for audiences to see.

In September 1936, General Francisco Franco supposedly claimed that there were “four nationalist columns approaching Madrid, and a fifth column inside of it ready to attack”.

Leon Trotsky did not support POUM and went on to disassociate himself from them and their actions. George Orwell joined POUM when he went to Spain to volunteer to fight against the Spanish nationalists

Formed by volunteers from outside of Spain and almost entirely Stalinist in leadership and political orientation

For example, the Castilian dialect serves as the basis of the modern Spanish language

“Moral Strength Through Material Defeat? The Consequences of 1898 for Spanish Military Culture”, Geoffrey Jensen, War and Society vol. 17, pp. 25-39 (October 1999)

"Spain’s First Democracy: The Second Republic, 1931-1936”, Stanley Payne (1993)

“The Collapse of the Spanish Republic: 1933-1936”, Stanley Payne (2006)

ibid.

ibid.

“The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s”, Piers Brendon (2002)

Average wages increased by 10% for workers between 1931 and 1933

ibid., Payne (2006)

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of the page to like this essay. Use the share or restack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so (be nice!).

As mentioned above, this essay was requested by someone with a large platform. I hope that you enjoy reading it. If you want me to continue telling the story of the Spanish Civil War in this way, please subscribe to my Substack to support my writing. I hope that you do because I really do want to continue writing this series.

I loved this and would love to see more on the Spanish Civil War.