Srdja Popovic - Global Mercenary On Behalf of Colour Revolution

Regime Change and Colour Revolutions Part 6

“You must wash more often. How many times do I have to tell you? Soap and water, Mussolini, soap and water!”

Angelica Balabanoff to a young Benito Mussolini

Angelica Balabanoff is a mostly forgotten figure today, which is unfortunate. She was a communist (and later social-democrat) activist and revolutionary, during an era in which this profession was a quick way to earn a very lengthy prison sentence, if not torture and execution.

She was also Secretary of the Comintern (Third Communist International) from 1919-20. The task of the Comintern was “to struggle by all available means, including armed force, for the overthrow of the international bourgeoisie and the creation of an international Soviet republic as a transition stage to the complete abolition of the state”.1 In short, she was for a time one of the most important figures trying to export global communist revolution to the wider world.

The Russian Revolution saw the first successful communist-inspired and led seizure of power, allowing for the creation of the Soviet Union, which then served as a safe haven for communist revolutionaries like Balabanoff. The failure of the Marxists in Berlin, Bavaria, Hungary (and elsewhere) shortly after the end of the First World War made the USSR all that more important to these revolutionaries, and made Lenin and the Politburo all the more influential when it came to their stated desire to turn the world ‘red’.

The establishment of this base for global Marxist revolution saw communists of the now-defunct Second International flock to the Soviet Union to take positions in state organs, help build the apparatus of the state, and obtain new instructions on how to export the revolution worldwide. The vehicle for this would be the Third International aka Comintern (founded in 1919), in which Balabanoff served. Where previously these agents had to rely on money donated to them from sympathetic wealthy sponsors, or on proceeds from criminal acts like bank robbery, they could now be certain that their actions would draw funding from the Soviet state, making their designated tasks a bit easier to plan and execute than previously.

This was the era of the (first) “Red Scare”. Europe and North America were gripped by the fear (and for some, hope) that the communist revolution that had taken over the Russian Empire would succeed in their countries as well. Bela Kun and his revolutionaries had seized power in Budapest after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg threatened to capture Berlin in 1919 when they led the Spartacist Uprising. A Soviet republic was declared in Bavaria in April of 1919. Communists were agitating for revolution throughout the western world, destabilizing regimes and threatening bloody “revolutionary violence” at the same time.

This necessitated a reaction that resulted not only in the defeat of these short-lived regimes and the executions of their ringleaders, but also in stronger legislation targeting communists and agents of the Comintern in many of these countries. Global revolution had failed, for now. However, its spirit was far from extinguished.

These revolutionaries were very, very serious people. Many like Balabanoff gave up a life of luxury (her family were wealthy Russian Jews from Chernigov, in today’s Ukraine) to risk their lives daily to spread a revolution that they believed would emancipate workers from a capitalist system that was highly exploitative. Prior to the establishment of the Comintern, these agents of global communism lived a cloak and dagger secret agent lifestyle, moving from safe house to safe house, using code names, and having possession of several different forged passports to help them enter or flee countries when necessary.

Theirs was not an easy life. Under constant monitoring by secret police, they moved from city to city, country to country, in order to gather, organize, and coordinate their efforts. Balabanoff, for example, was residing in exile in Switzerland in 1912 when she encountered a young Italian socialist named Benito Mussolini:

In 1912 Angelica Balabanoff, editor of the socialist newspaper Avanti!, took a promising young journalist out to lunch and offered him a job as her deputy. She had one condition: “You must wash more often. How many times do I have to tell you? Soap and water, Mussolini, soap and water!”

When she wasn’t lecturing Mussolini on the need for proper hygiene, Balabanoff was conferring with radical communists like Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Julius Martov. Zurich at the time was filled to the brim with revolutionary Marxists from across the whole of Europe, and Balabanoff segued easily between the various national groupings on account of her proficiency in several different languages.

Even though the establishment of the Soviet Union provided a safe haven for agents of the Comintern, the success of the Russian Revolution made their work that much harder in the rest of Europe, as Europeans feared bloodshed like that which resulted from the revolutionary violence that accompanied it and viewed these revolutionaries as little more than “terrorists” (except, of course, those who were sympathetic to their goals). Many communist parties were restricted in their activities, some were outlawed altogether2, and communists were put under the watchful eye of state security.

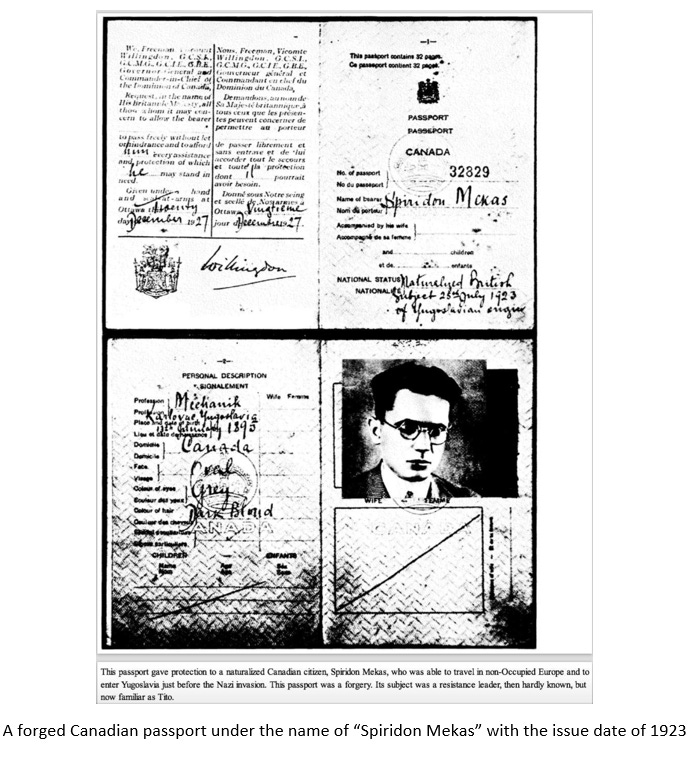

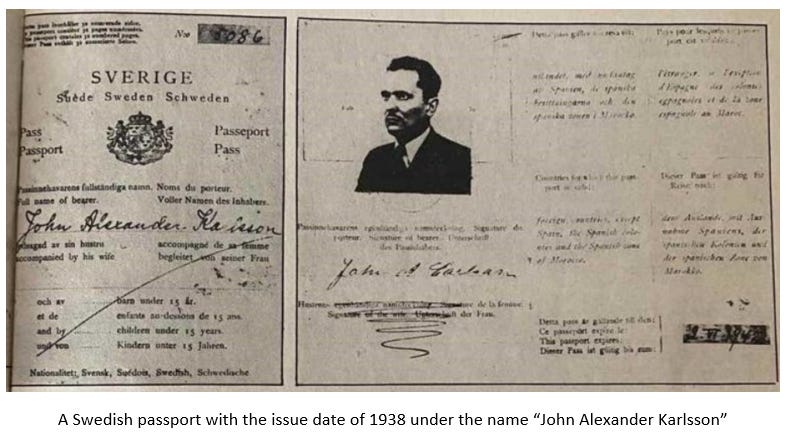

Many states did not recognize the Soviet Union at first, meaning that Soviet-issued passports were worthless for travelers from that country. Comintern agents would have to rely on forging stolen passports from other countries. Comintern agent-turned communist dictator of Yugoslavia Tito was a typical example. He had several different passports under different names while traversing the continent, doing work on behalf of global communist revolution:

You don’t have to like them, but you do have to respect these communist agents for their fanaticism and their willingness to risk their lives in the name of revolution. What they all had in common was the unshakeable faith that communism was inevitable, and that it would free the exploited classes around the world. Theirs was a global jihad. Surveillance, imprisonment, torture, and execution were all part of the package that came with it.

The failure to create new Soviet states in Europe outside of the Soviet Union resulted in a change of course instituted by Joseph Stalin shortly after Lenin’s death. This was known as “Socialism in One Country”, a policy adopted by the Soviet Union in 1926 that emphasized the need to defend the Soviet Union over the pursuit of global revolution. Trotsky and Zinoviev protested this change in policy vigorously, arguing that it was heretical to Marxism, as permanent (i.e. world) revolution was a core tenet.3 This split led directly to Trotsky's expulsion from the Communist Party, and later his exile (and assassination).

The Comintern would continue to function throughout the 1920s and 30s, but it would take a back seat to defending the Soviet Union. In the meantime, “Global Revolution” was put on hold.

A New Era, A New Secular and Universal Creed

The fanaticism and fervour that marked the Marxists of the first half of the 20th century in the West began to slowly dissipate during the course of the Cold War (while gaining currency in the developing world) for various reasons ranging from the “outrages” of Stalinism to the inability of Marxist-Leninism to compete with western capitalism. This dissipation led to evaporation by the end of the 1980s as the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviets withdrew from Central and Eastern Europe. The final nail in the coffin was the dissolution of the USSR. Faith in Marxism had collapsed, and what was left of its global revolutionary potential resembled ashes from a fire extinguished long ago.

It was around this time that American Political Scientist Francis Fukuyama wrote an article in The National Interest which was provocatively titled “The End of History?”. In it, he argued that market-oriented parliamentary democracies had been proven to be superior to all other forms of state organization, and that they were inevitable, despite challenges to them that existed then and will present themselves in the future. Fukuyama went on to turn his essay into a book entitled “The End of History and the Last Man”, one that I have referenced quite a bit on this Substack over the past two and a half years.

Fukuyama’s work is both important and has proven to be very influential since it was published in 1992. It was emblematic of the triumphalism on display in the West (especially in the USA) in the wake of the end of the Cold War. One superpower was left standing over the ruins of its sole competitor, its economic and political systems evidently superior to all alternatives.

Fukuyama agreed with both Hegel and Marx that history was both linear and progressive, not cyclical as per Oswald Spengler. The triumph of democracy and free markets represented to Fukuyama a natural historical progression that all others would have to adopt for themselves, lest they be swept up in the proverbial ‘dustbin of history’. Much like the agents of the Comintern believed that communism was inevitable, so too did (and still does) Fukuyama believe in the inevitability of global liberal democracy.

Fukuyama has had to constantly explain himself over the past three decades regarding his argument in order to clear up any misconceptions that arose from it. In 2007, he sought to set the record straight, insisting that he did not intend for his book to be an argument in favour of ‘exporting democracy’:

Finally, I never linked the global emergence of democracy to American agency, and particularly not to the exercise of American military power. Democratic transitions need to be driven by societies that want democracy, and since the latter requires institutions, it is usually a fairly long and drawn out process.

Outside powers like the US can often help in this process by the example they set as politically and economically successful societies. They can also provide funding, advice, technical assistance, and yes, occasionally military force to help the process along. But coercive regime change was never the key to democratic transition.4

…at the same time, he’s talking out of both sides of his mouth as he lists examples of how the USA can “help facilitate” democracy globally, contradicting himself by including “occasional military force”.

What Fukuyama had done was give political and philosophical cover to the expansion of US Empire in the vacuum created by the collapse of the Soviet Union. The “New World Order” declared by George Bush the Elder would be one where “human rights”, “rule of law”, and free markets would be prerequisites for “democracy”. Those that did not adhere to these values would become targets of US foreign policy designs (with notable exceptions, of course).

Realism was now gauche and retrograde. The idealism of exporting democracy (whether spouted cynically, or championed earnestly), was to serve as the facade of imperial expansion. This facade required constant reinforcement of the criticism that US targets of regime change fell outside of the narrow definition of democracy, and that the citizens of those countries yearned to be free of the “dictatorship” or “autocracy” under which they lived. They wanted democracy, and that would require either revolution or invasion. For a revolution, you need revolutionaries. For a global revolution, you need global revolutionaries.

Fukuyama’s positive vision of a democratic future appealed to many instantly, resulting in the wide popularity of his book. Among those enamored by his arguments for the inevitability of global democracy were the US neo-conservatives. The origins of neo-conservatism lie with a cohort of intellectuals who defected from the Democrats to the political right during the 1960s, urging a more forceful approach to pursuing US interests abroad (including the promotion of democracy) while criticizing the liberalism of LBJ’s “Great Society”, and the overall shift in American culture by the end of that decade.

Leading lights of early neo-conservatism included Irving Kristol and James Burnham. Like other early neo-conservatives, both of these men were originally Trotskyites, which meant that they harboured a burning hatred of the Soviet Union, transforming them into Cold War hawks. Being Trotskyites, global revolution was a non-negotiable position for them. Dropping Marxist-Leninist philosophy in favour of liberal democracy and free markets, their revolutionary fervour found a new vehicle in the form of the superpower USA, the only country that could vanquish the nemesis that was the Stalinist (and post-Stalinist) USSR. By the 1980s, a fanatical devotion to Israel also became a core tenet of US neo-conservatism, which by that time had made significant inroads into policy-making via their inclusion in the Reagan Administration.

Fukuyama’s prophecy of global democracy fit snugly within neo-conservatism’s push for US imperial expansion in the post-Cold War era. It also meshed well with the rise of “humanitarian interventionism” in the 1990s. Despite minor (and less minor) differences between these three in how they proposed that the USA pursue its interests abroad, the three combined have largely defined the course of American foreign policy ever since.5

Srdja Popovic - The Making of a Global Revolutionary

Imagine if Chris Hayes and Rachel Maddow of MSNBC got married to one another. Imagine if MSNBC was the only TV news available for viewing in the USA. Imagine still if this power couple (and all of their colleagues) reported on the news in a way that fully aligns with the White House’s positions and policies (kinda like it does now).

Now imagine if Hayes and Maddow had a son who would go on to lead the youth wing of a national political party. If you can imagine all of this, then you can begin to understand who Srdja Popovic is.