Saturday Commentary and Review #79

Curtis Yarvin: His Power Grows, The Cheapening of What US Citizenship Means, De-Policed Seattle, "Winning Ukraine" is Actually Losing, JFK Jr.'s George Media Experiment

For some strange reason, much of the internet culture of the second half of the first decade of this new century that has gone on to influence politics completely passed me by. I missed the Something Awful Forums, not at all realizing that the site actually had a forum. I thought it was a Fark.com humour site, but without comments. Something Awful Forums has resulted in not just creating a strain of internet culture, but propelling certain forum members to notable positions, such as Eliot Higgins aka Brown Moses, who works for MI6 cutout Bellingcat.

I also completely missed out on the Mencius Moldbug phenomenon. I was completely unaware of his existence until the tail end of his blogging, some time around 2014. The internet is a big place (while continuously getting smaller), and it’s easy to miss things.

What information I got about Moldbug was entirely second-hand; from friends on an internet forum that I was on. I was informed that he was a guy who wrote very long posts on political philosophy, was some sort of monarchist, and that he championed tech billionaire visionaries like Elon Musk to run the USA like a corporation. The only conclusion that I could infer from that was that Moldbug was a computer nerd.

During the Trump Administration, our circles began to overlap as his reputation post-Unqualified Reservations (his blog) only grew in stature. He reached out to me last year and we began an occasional correspondence that resulted in the interview that I conducted with him (a wildly popular one) which you can read here.

Yarvin and I have reached the same conclusion on one of the major questions of our time: the ability of the US Empire to persist. Both he and I are in agreement that the death of the USA is 100% wrong and not imminent, and that it can continue in one form or another for at least another century. Where I use the term “Turbo America” to explain how a morphing USA will behave going forward, Yarvin instead sees the US Empire stumbling ahead thanks to the historical momentum it has built up.

Jacob Siegel of Tablet Mag has written a rather interesting piece on Curtis Yarvin this past week that I want to share with you. For many of you, this material won’t be new. For others, it presents a thinker that many only whisper about.

The reputation:

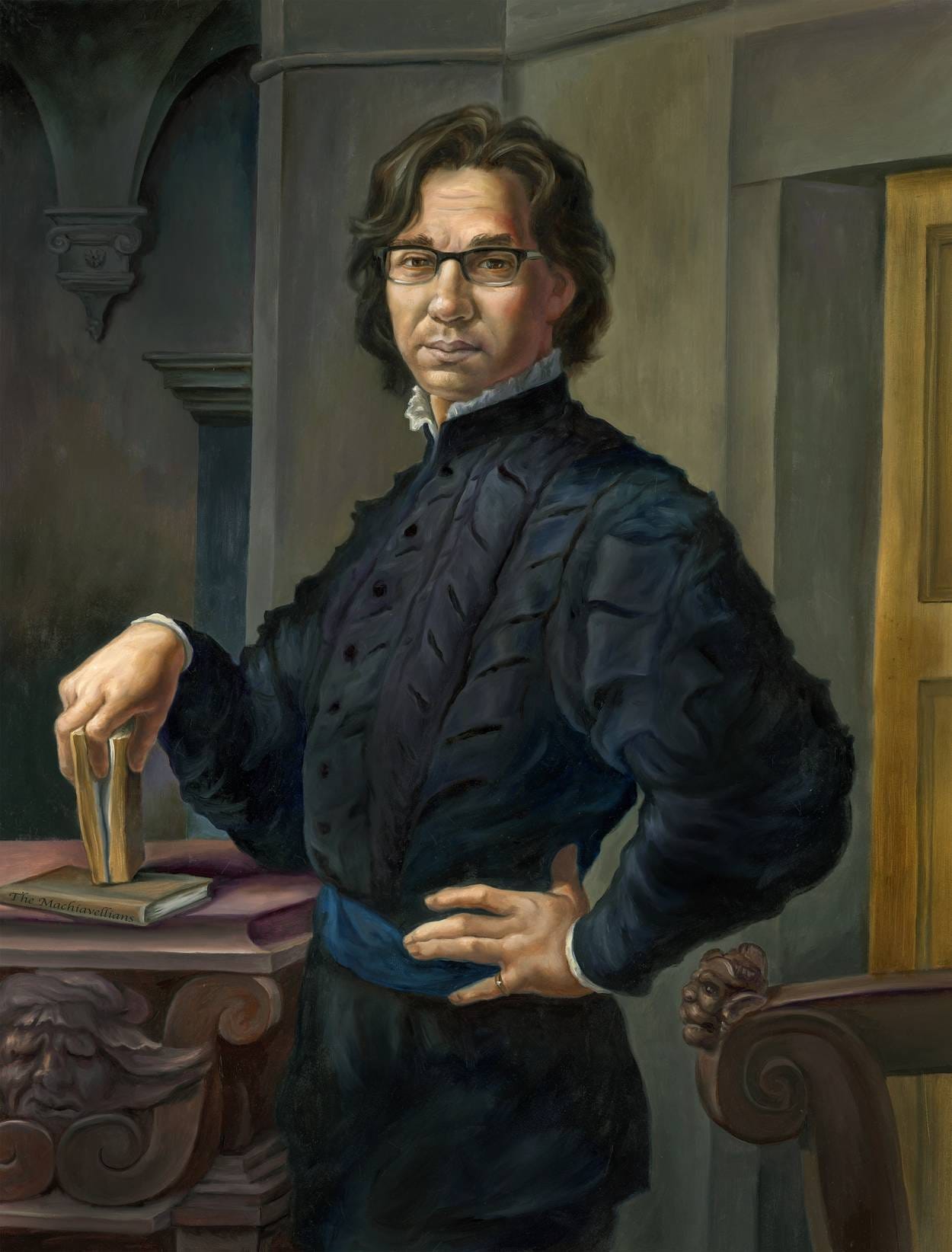

Like Niccolò Machiavelli, to whom he is sometimes compared, Yarvin defines himself as an amoral realist who invented a new theory of government that upends established doctrines of political morality. Starting in the late 2000s, his name—not his real name, he was still known then by his blogging pseudonym—began to be whispered among some of the most powerful people in the country, a secret society made up of disaffected members of the American elite.

Shortly after Donald Trump entered the White House, reports started to circulate that Yarvin was secretly advising Trump strategist Steve Bannon. His writing, according to one article, had established the “theoretical groundwork for Trumpism.”

Yarvin denied the rumors, sometimes playfully and at other times strenuously. But he was consistent in his criticisms of the Trumpian approach to politics. Mass populist rallies and red MAGA hats struck him as merely a weak imitation of democratic energies that had already died out. “Trump is a throwback from the past, not an omen of the future,” he wrote in 2016. “The future is grey anonymous bureaucrats, more Brezhnev every year.”

The actual:

What Yarvin is, if one wants to be accurate, is the founder of neoreaction, an ideological school that emerged on the internet in the late 2000s marrying the classic anti-modern, anti-democratic worldview of 18th-century reactionaries to a post-libertarian ethos that embraced technological capitalism as the proper means for administering society. Against democracy. Against equality. Against the liberal faith in an arc of history that bends toward justice.

His most important concept, The Cathedral:

In Yarvin’s worldview, what keeps American democracy running today is not elections but illusions projected by a set of institutions, including the press and universities, that work in tandem with the federal bureaucracy in a complex he calls the Cathedral. “The mystery of the Cathedral,” Yarvin writes, “is that all the modern world’s legitimate and prestigious intellectual institutions, even though they have no central organizational connection, behave in many ways as if they were a single organizational structure.”

Living Americans might be able to glean a sense of the phenomenon Yarvin describes in the current public discourse. It has often seemed in recent years that every few weeks has brought a new instance in which journalists and experts instantaneously, almost magically converged on shared talking points related to the hysteria du jour—cycling through moral crusades to free children from cages at the U.S. border, save the post office from a fascist coup, label the filibuster a tool of white supremacy, and so on. The power of the Cathedral is that it cannot be seen because it is located everywhere and nowhere, baked into the architecture of how we live, communicate, and think.

The main reason why I insist that the US Empire is not failing, despite operational fuckups like Afghanistan, is because the elites are wholly united. One need only look at how easily they managed to strangle the Trump Administration from outside of it and within it. People voted for Trump because they wanted an end to politics as usual, an end to elitist rule that didn’t take the people into consideration. In short, they wanted a revolutionary. The problem with revolutions is that you need segments of the existing elite to defect in order to effect a revolution. What the Trump Era showed us is that US elites are as united as ever.

The failure of democracy is that it almost immediately creates an oligarchy enforced by a rigid bureaucracy aka Deep State:

If democracy is so decrepit and ineffective, one might ask how it is that America became the world’s great superpower and maintained that position for the last century. Yarvin’s answer contains two parts: first, that nothing lasts forever. Second, while American supremacy may once have rested on innovation and growth, the country, now a bloated empire, has been surviving for decades on the power of myth-making and mass illusions.

Whether or not he can be compared to Machiavelli the man, it is correct to describe Yarvin as a Machiavellian, in the meaning given to that term by the American political writer James Burnham, a one-time follower of Leon Trotsky who later became a committed anti-communist. Like the historical figures chronicled in Burnham’s book The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom, Yarvin believes that one of the worst aspects of democracy is the fact that it rarely exists. Because democracy is the rule of the many, and the rule of the many is inherently unstable, democracies rarely last long.

Burnham argues that all complex societies are in effect oligarchies ruled by a small number of elites. To hide this fact and legitimize their rule in the eyes of the masses, oligarchies employ the powers of mystification and propaganda. Indeed, Yarvin believes that America stopped being a democracy sometime after the end of World War II and became instead a “bureaucratic oligarchy”—meaning that political power is concentrated within a small group of people who are selected not on the basis of hereditary title or pure merit but through their entry into the bureaucratic organs of the state. What remains of American democracy is pageantry and symbolism, which has about as much connection to the real thing as the city of Orlando has to Disney World.

In place of a functional democratic system, Yarvin came to believe, there now exists an industrial-scale symbolic apparatus that generates the illusion of political agency necessary for society’s real rulers to carry out their business undisturbed. American voters still go to the polls to pick their leader, but the president is a ceremonial figure beholden to the permanent bureaucracy.

There is no doubt that this last bolded portion above is absolutely correct. The notion that 330 million Americans can be served by only two parties is laughable. But it’s the illusion of individual power that matters, not the actual practice.

Yarvin’s proposal:

Having concluded that democracy is a failed and dying form of governance, one that increasingly produces more disorder than order, Yarvin provided a vision for what could come next: an enlightened corporate monarchy that would only arrive after a hard reboot of the political system. It was a vision of total regime change, but one achieved without any violence or even activism since those efforts were doomed to fail and would therefore only strengthen the system they sought to overthrow. For those who believed in it, the next step was to generate the ideas that a future elite would use to run the country once it seized power.

And who should the rulers be, exactly? Rather than a hereditary dynasty, Yarvin proposed the Elizabethan structure of the joint-stock company used by the British East India Company as the best means for selecting and overseeing the monarch. The state, rather than tyrannizing its subjects or being controlled by citizens who endowed its authority, “should be operated as a profitable corporation governed proportionally by its beneficiaries.” Elsewhere, he puts it differently: “I favor absolute monarchy in the abstract sense: unconditional personal authority, subject to some responsibility mechanism.”

A valid criticism from Jacob:

It also misses the fatal weakness of Yarvin’s ideology: For all of its power as a systemic analysis, it contains no place for human beings. The classic question in philosophy—what is the good life?—never intrudes on Yarvin’s pursuit of designing beautiful machines.

Yarvin has for several years now been persona non grata in polite company, but do not think for a second that important people are not paying attention to him.

Michael Lind, one of my favourite writers on the scene at present, has written a nice companion piece to the one above on Curtis Yarvin. Where Yarvin discusses the decline of democracy into Oligarchism enforced by a permanent bureaucracy, Lind has written a piece about the degradation of the concept of citizenship in the USA. Might the two be connected? I certainly think so.

Citizenship once used to mean not just rights, but duties that earned those rights. Those days are long gone. Citizenship in many places is now reduced to legal access to government programs, shorn of all duties. Is it any wonder why so many people in less developed countries seek to migrate to places like the USA where one can gain the advantage of handouts without doing anything in return? People like free stuff.

More concerning, from my perspective, is how post-national elites view citizenship as an encumbrance to extending power globally. Why not extend government largesse to states overseas to ensure businesses access to those markets or its resources?

The devaluation of US citizenship:

Long before the United States began selling green cards—the tickets to U.S. citizenship—to rich foreigners by creating the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Visa Program in 1990, American citizenship had been devalued. From the days of the Greek city-states and the Roman republic to the city-republics of the Renaissance and the cantons of Switzerland, citizenship in the fullest sense originally involved active participation of citizens—a group not only male but also usually smaller than the population as a whole—in the government of their communities, as electors, office-holders, jurors, and citizen-soldiers.

In practice, the ideal of the amateur, omnicompetent citizen—a member of the militia today, a town or county council member tomorrow and a juror next week—could be realized only in small, relatively undeveloped communities. The ideal of the self-sufficient family farmer with a musket and a copy of the Constitution on the fireplace mantle was a casualty of economic centralization and modernization. Most Americans are proletarians who live from paycheck to paycheck, and a majority of American workers are employed by firms with more than 500 employees and supervised by salaried corporate bureaucrats.

The ideal of the male citizen-soldier who earns his civil rights by contributing to the defense of the republic survived for a while by being transferred to the colossal modern nation-state, whose citizens, mostly unknown to one another, are united by common culture, institutions, location, or some combination of the three. For a time, the mass national conscript army and its reserves were thought of, however implausibly, as the heir to the local militia. The older tradition of civic republicanism inspired the linkage of military service to government benefits like the GI Bill and other privileges for veterans. That link was all but eliminated by the abolition of the draft in 1973. Today’s American military is a professional force, more like those of premodern European bureaucratic monarchies than frontier militias.

The right to vote remains, but its power has been diluted, even as it has been extended in law and practice—first to white men without property, then to white women, and finally to nonwhite citizens. In a world of industrialized nation-states, in which even small countries are vastly more populous than the city-republics of antiquity and the Middle Ages, scale alone ensures that the influence that any one individual can exert by voting periodically in free and fair elections is negligible.

What citizenship is today:

While the positive duties formerly associated with citizenship have gradually been discarded, there has been a trend to establish government requirements for the provision of positive rights or benefits, from public or publicly funded education and public retirement spending to guaranteed health care. As a result, in the United States and other Western democracies, it is widely accepted in the 21st century that national citizens have a right to various public goods and welfare services without any need to earn the benefits at all, purely on the basis of their status as citizens of a particular nation-state.

and:

One by one, then, the requirements and duties historically associated with republican citizenship—such as property ownership, a degree of economic independence, and service in the citizen-military—have dropped away, leaving citizenship finally as a mere right to government welfare, along with just treatment under the law.

The effect:

Without any obligation on the part of citizens to earn their legal privileges or welfare benefits by serving the political community, the modern nation-state based on common culture or ethnicity becomes a tribal trust fund, rather like those managed by the U.S. federal government on behalf of Native American nations.

And what the near future portends:

Aiding in this effort is the tendency of the mainstream press in the United States and other English-speaking countries—which is to say, the elite center-left press—to erase any distinction between legal and illegal immigration. Increasingly, the words “immigrants” or “migrants” are used to describe both authorized and unauthorized immigrants.

This final point brings up the question of 'equality’: how is it fair for those in less developed countries to not be able to access the government services of richer countries? This argument will be used, along with “Climate Emergencies”, to push through newer, much more massive waves of migration to the western world.

My Uncle in Germany likes to say that unintended consequences are not unintended at all, as they are subliminally desired: “they got what they were looking for”.

This accurately sums up the hilariously short-sighted push to ‘defund the police’ that spread across the USA in 2020 like the proverbial wildfire. “Actions have consequences”, said that weird Polish woman in David Lynch’s “Inland Empire”, and these consequences are now playing out in places like Seattle, where a decimated police force has resulted in everything that can wrong actually going wrong.

One of the most important things that the state can provide its citizens is law and order. If you cannot provide that, the trust accorded to the state vanishes rather quickly. Some liberals are now having second thoughts about defunding police forces, with T.A. Frank of Vanity Fair laying out the case for doing so, using Seattle as an example.

The disastrous present condition:

This February, Bruce Harrell, newly installed as mayor of Seattle, made it official that his city has gone into decline. “The truth is the status quo is unacceptable,” he said in his first state of the city address. “It seems like every day I hear stories of longtime small businesses closing their doors for good or leaving our city.” But it’s not just small businesses. In mid-March, Amazon announced that it was abandoning a 312,000-square-foot office space in downtown, citing concerns over crime.

That such woes should afflict one of the richest cities in the country, with a median household income of over $100,000, cannot be blamed on economic decline. Yet much of Seattle’s core looks like a pockmarked ghost town. Businesses on both sides of Third Avenue, a major thoroughfare, are boarded up. Blocks from the Four Seasons hotel and the Fairmont Hotel, tents crowd the sidewalks, and drug users sit under awnings holding pieces of foil over lighter flames. Traffic enforcement is minimal to nonexistent. The year 2020 saw a 68% spike in homicides, the highest number in 26 years, and the year 2021 saw a 40% surge in 911 calls for shots fired and a 100% surge in drive-by shootings. Petty crime plagues every neighbourhood of the city, and downtown businesses have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to fund their own security.

The riots that occurred in the wake of the killing of George Floyd saw Seattle set one fire, and police officers forced to work 12 hour shifts (often 16 hours, actually), six or even seven days a week. Being handicapped by their political leadership took a toll on their morale:

When the protests grew violent, police officers began to use various non-lethal weapons to control the crowd, including pepper spray and tear gas. This led to complaints, lawsuits, and stinging condemnation in the local press. On 5 June, Seattle’s mayor, Jenny Durkan, declared that officers “do not need to be using tear gas at protests as a crowd management tool” and banned the use of it for 30 days. Many officers felt they were being asked to maintain order in violent crowds while surrendering all of their crowd-control tools. “People were throwing bottles and rocks, and we had to split this thing up. God forbid after multiple, multiple, multiple warnings that we’re gonna throw gas, guys, you better disperse, we throw gas,” says J.D. Smith. “So then what? Oh, Seattle PD, look how heavy-handed they are.”

The local elites turned on their own police force:

“In May of 2020, our political leadership considered us a necessary evil,” says Chris Young. “In June of 2020, they started to think that we were an unnecessary evil. Every cultural institution in the city turned on the police.” That included educational institutions. In early June, Young, as a parent of children in Seattle Public Schools, was one of thousands of recipients of an email from school superintendent Denise Juneau announcing that cooperation with the police would be suspended in light of “the perpetuation of systemic racism, the murders of Black people by police officers across our country, [and] the violence displayed by some law enforcement officers here in Seattle”.

Abandoning precincts:

On Sunday 8 June, Matthew Kruse and coworkers from the North Precinct got an order to go down and help back up his colleagues in the East Precinct on Capitol Hill. The plan, he says, was to let crowds march past the precinct unimpeded, unless there was criminal activity, and Kruse and his colleagues were stationed a couple of blocks away, watching the area on camera. No one was trying to break into the precinct, says Kruse, but people started to pitch tents near it. At that point, according to Kruse, a police captain went over to talk to the protesters. “He started talking to protesters and telling them, hey, you guys have got to move along, and they got in a verbal altercation,” says Kruse. “Then they [senior officers] came back to us and said we’re just going to let them stay there and do their thing.” The East Precinct, already boarded up, was now abandoned.

Resulting in another heavy hit to morale:

News of the surrender of the East Precinct hit cops hard. “I just felt sick,” says Chris Young. “It was humiliating.” Matthew Kruse found the about-face on holding the fort versus leaving it insulting. “At first they had said: no, we’re not going to let them take the precinct,” says Kruse. “The next day it’s being cleared out.” J.D. Smith remains incredulous. “I’m still embarrassed,” Smith says. “We gave away a precinct.”

The infamous CHAZ:

What followed for the next few weeks was an impromptu test site for improvised maintenance of public order in what came to be called the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, or CHAZ. A few days into the CHAZ, the New York Times described it as “an experiment in life without the police — part street festival, part commune.” Donald Trump weighed in from the Oval Office to condemn it. “Domestic Terrorists have taken over Seattle,” he tweeted. Seattle’s mayor, Jenny Durkan, responded, “It’s not terrorism. It’s patriotism.” Asked by CNN’s Chris Cuomo how long the CHAZ would last, Durkan quipped, “I don’t know. We could have the summer of love.”

For police stationed out of the East Precinct, there was no base of operations anymore. “They couldn’t deploy from there,” says Matthew Kruse. “They had to deploy from the West Precinct or North or South or Southwest or any other precinct. So response times got slower, and that affects everyone from a shop owner to a person who lives there.”

Where some observers saw a harmless street fair others saw something more menacing. “All these businesses are failing and they’re asking for help,” recalls J.D. Smith. “There is nothing, and I mean zero, we can do because the mayor is saying summer of love.” Chris Young says that officers received an email instructing them not to enter the six-block zone of the CHAZ, although he made his way into the off-limits area after some unsuccessful arson attempts against the precinct building. “I was sent with a fancy camera to take pictures of the crime scene of where they tried to burn it down,” says Young. “You had to go by a checkpoint with guards, and God knows what they’d do with me if they found out I was a cop. I had to basically go undercover to sneak in and look at my own precinct.”

CHAZ quickly descended into violence and death:

The CHAZ lasted another ten days after that, until Wednesday 1 July, when officers reclaimed the precinct without a struggle. In the meantime, a 17-year-old had been shot in the arm on 21 June, a 30-year-old male shot and wounded on 23 June, and two black teenagers, 14 and 16, shot and wounded on 29 June as they drove into the CHAZ. The older of the two, Antonio Mays Jr., died of his wounds. Witnesses have stated that members of CHAZ security were the ones who opened fire on them, but police have never tracked down the responsible parties.

Another hit followed against senior police:

Despite the retaking of the East Precinct, the city continued to be racked by protest and strife throughout July, with further vandalism and looting by a subset of the protesters, few of whom ever faced charges. City officials continued to direct their ire toward the police department instead, and on 10 August the Seattle City council voted to cut the pay of senior police staff, including Chief Carmen Best, who enjoyed widespread respect from officers on the force, including all of those interviewed for this article. “It was demoralising,” says Chris Young. “She was a great chief and a very progressive leader who happens to be black. But she still got run out of town on a rail because she wouldn’t agree that her department needed to be abolished.”

Carmen Best immediately announced her resignation. At that time, T.J. San Miguel, who calls Best “excellent, just excellent,” was already deep into looking for an exit. A move like that, when she’d spent years to secure the job of her dreams, working in the K-9 unit, would have been unthinkable in the recent past. She considered herself one of the biggest cheerleaders of the department. But the hostility from the city in June and July changed her outlook. “I realised I could do everything completely right, and if the optics aren’t good, then they’re going to hang me out to dry,” she says. “Once I came to that realisation, it was like a bad breakup where you just shut somebody off.” San Miguel left the force when Best did.

Without political backing, Police have no cover in which to operate. Who then would want to be a police officer? You’d have to be a sociopath or an idiot to work in such an environment.

Further erosion of law and order followed the Police Chief’s resignation:

A change in public safety began to be noticeable across the city, not just in protest zones. Seattle’s city attorney, Pete Holmes, and King County’s prosecuting attorney, Dan Satterberg, had always taken a lenient approach to so-called quality-of-life crimes, but after June 2020 they began to ease up across the board toward a range of other offences. Most of those who committed vandalism or looting during the protests escaped any punishment. Matthew Kruse said that storeowners would call the police about shoplifters, not realising that prosecutions of that offence had effectively ceased. On one occasion Kruse and his partner watched a man walk into a store, shoplift about $20 in goods, and walk out. “He was like, what are you guys going to do — arrest me?” says Kruse. “And we knew we weren’t going to arrest him, because with any misdemeanour stuff, we had to go through the prosecutor, and stuff like that wasn’t going to get prosecuted. You could I.D. the suspect and could get a full confession, and they were going be like, ‘We’re not gonna take it.’”

What has resulted is what was described at the top of the article. Seattle has gotten what it asked for.

The erection of a parallel reality buttressed by a constant flow of propaganda and disinformation, compounded by a circular set of talking heads, magnified by wishful thinking, tells us that Ukraine is winning its war against Russia.

Actual reality is a different matter altogether. Shorn of its south, denied resupply of necessary resources to continue fighting, immobilized in many places, the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) are hunkered down in the very strong defensive positions that they had eight years to build and fortify, but which are now suffering the effects of attrition.

This is politics by warfare: Russia can now clearly be shown to want a negotiated deal with the West over Ukraine, even if the USA and UK want to bleed it to death. Otherwise, the Russians would have simply ‘shocked and awed’ Ukraine. Russia is creating facts on the ground to present Ukraine and the West a fait accompli, despite western propaganda to the contrary.

If Ukraine was winning, it would not be signalling its acceptance of painful concessions.

In recent days, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky walked the first steps toward peace by announcing his openness to making several concessions to Russian demands. These include a commitment to Ukrainian neutrality with respect to military alliances, a rejection of any nuclear arsenal, and an acceptance of Russian control over Ukraine’s eastern regions. He even indicated a readiness to change language policies that had disadvantaged Russian speakers. Zelensky’s announcements gave the face-to-face talks convening this week in Istanbul some hope of a cease-fire.

More:

In the middle of a war that threatened Ukraine’s existence as a nation, Zelensky and Ukrainians finally seem to have realized that they will have to give up on their aspiration to join the Western defense alliance and probably erase that aspiration from their constitution.

After negotiations on Tuesday, the Russians seemed to believe that their Ukrainian counterparts were no longer interested in being a part of NATO, and they described the Istanbul talks as “meaningful.” They said Russia would “reduce military activity” near Kyiv and the northern Ukrainian city of Chernihiv, and that they were encouraged to organize a meeting between Zelensky and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin sooner than initially envisaged.

“We have received Ukraine’s written proposals confirming its striving toward a neutral, off-block, and nuclear-free status, with a refusal from the production and deployment of all types of weapons of mass destruction,” said Russian presidential aide Vladimir Medinsky, who led the Russian delegation in the talks, according to the Russian news agency TASS. “We have received these written proposals.”

Collective obligations:

Paikin added that Ukraine is looking for a collective obligation to defend Ukraine’s territorial integrity in the event that its neutrality is violated. “In theory, this should represent a viable option to respect the rights of countries in the Euro-Atlantic space that want to be neutral,” he said. It seems unlikely, however, that the West will make any promises that amount to directly being involved in any future conflict, either.

The other major issue between the two countries is the status of the eastern regions. In 2014, as popular protests led to the fall of Russia-backed Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, Russian separatists in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk declared independence. Back then, Russia responded to the revolution by annexing Crimea, and this February it declared Donetsk and Luhansk as independent republics, claiming that their protection was one of the main aims of the invasion. Russian troops have steadily infiltrated the eastern and southern regions to carve a land bridge from Crimea to Donetsk and Luhansk, and bombarded cities that stand in the way. It has so far occupied Kherson and carpet-bombed Mariupol, which is the only barrier standing in the way of the bridge.

Reality sets in:

In a conversation with Russian journalists before the talks on Tuesday, Zelensky alluded to a compromise. “I understand it’s impossible to force Russia completely from Ukrainian territory. It would lead to third world war,” he said. “I understand it, and that is why I am talking about a compromise. Go back to where it all began, and then we will try to solve the Donbass issue.” Ukraine is mindful of how unpopular conceding any territory might be and has decided not to give out the details of what a possible compromise might look like.

Does this sound like a side that is winning?

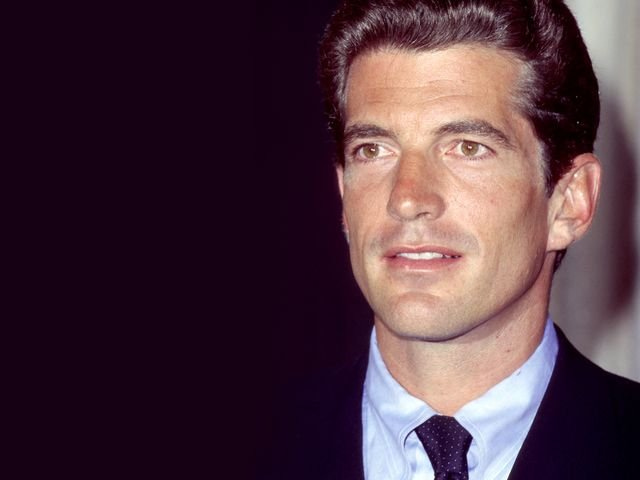

We end this week’s Substack with the story of the 90’s political magazine, George. Named in honour of George Washington, and founded by John F. Kennedy Jr., George provided a pop culture take on US and global politics. I was a reader at the time, a time where we were all much more naive about the media and its journalists (or is it a case that the quality of media and its writers has declined since then?)

An irreverent play on politics and pop culture with a dash of Kennedy intrigue, the Barrymore/Monroe cover accurately sums up George, the magazine Kennedy launched in September 1995. His concept, in today’s terms at least, seems relatively straightforward: “a lifestyle magazine with politics at its core.” Back then, however, George was revolutionary; there had never been anything quite like it. Nor had there ever been a magazine editor quite like John F. Kennedy Jr., a lawyer by training. Perhaps predictably, media critics sneered, lampooning him as aimless and unqualified, his idea frivolous. Esquire called the magazine “the riskiest venture of a pampered life indelibly marked by tragedy.” Newsweek: “Kennedy has been able to live without real responsibility, as a bit of a slob, considerate to his (many) women, not quite sure what he wants to do, looking forward to . . . the Frisbee game in the park. . . . Now, apparently, he’s ready to grow up.” The Los Angeles Times asked: “Is John Kennedy Jr.’s George making American politics sexy? Or is the magazine just dumbing it down more?”

But Kennedy’s instincts were right: In the twenty-plus years since his death, politics and pop culture have become so intertwined that candidates now spend nearly as much time courting voters on late-night shows as they do on the Sunday talk circuit. Politicians are covered as if they were celebrities, while celebrities seek out a voice on politics. The current president is largely a product of reality television, and his predecessor recently signed a production deal with Netflix. Oprah Winfrey has been seriously touted as a potential presidential candidate, as have—somewhat less seriously—The Rock and Mark Cuban. As the son of the thirty-fifth president and an elegant First Lady–turned–book editor, Kennedy was uniquely positioned to both cover and promote the marriage of politics and pop culture—because he lived it.

Read the rest here.

Thank you for once again checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you. And don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already yet.

I find most of Yarvin's analysis spot on, and strikingly original when you come across it for the first time. I'm less convinced by his prescriptions though, especially seeing his support for China's zero Covid policy.