Saturday Commentary and Review #174

Condi Rice Calls for Turbo America, Almost Everyone Now is a Fascist, US/CAN vs. Mexico's Judicial Reforms, Marxist to Rawlsian Liberal Pipeline, Who Killed Pasolini?

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

When Donald Trump caved into pressure and gave the order to lob a few cruise missiles against Syrian Government targets, Bill Kristol excitedly remarked: “for the first time, he is acting presidential!”.

The unrelenting torrent of accusations leveled against Trump from 2016 to the present has flooded every single aspect of political life in the USA and beyond. But make no mistake, it was the perceived threat that he appeared to pose to the bipartisan consensus on foreign policy that made him Public Enemy #1 in the eyes of the governing elites. Think about it: the first thing that Congress did when Trump entered the White House was to take power out of his hands regarding US policy towards Russia. From the very first minute of his time in office, he was handcuffed to the established bipartisan policy that insisted that the Putin regime be overthrown, or at least, increasingly isolated.

Trump’s approach to China yielded different results back home because his administration’s approach was completely aligned with the established consensus that sought a tougher approach to Beijing. I’m sure that there was some criticism of Trump and his China policy, but I can’t think of any offhand and I doubt that most of you could either. The Americans have been seeking to “Pivot to East Asia” for some time now, and part of this pivot demanded a somewhat more belligerent tone towards the Chinese.

In 2016, Trump ran on Patrick Buchanan’s 1992 platform of less intervention abroad and more economic protectionism. This put the fear of God into the foreign policy blob as such a radical turn away from traditional policy would have upended decades of established norms and, in their collective view, eroded US power on the global stage. Cries of “isolationism!” rang all across the media complex, with the implication being that so-called “isolationism” was tantamount to being a Nazi apologist, or whatever.

In 2024, Trump is running on a more moderate platform (for the most part), as his campaign is much more disciplined this time around. Still, he is not trusted, and the fears that he will “pull out of NATO” or strike some sort of grand bargain with Vladimir Putin persist. The REAL fear is that his return to office would demolish a carefully (you might disagree here) devised and implemented policy to maintain and expand the primacy of US global power at a time when revisionists seek to upend the order that has served the USA so well up until now.

It is this very fear that prompted former National Security Advisor Condoleeza Rice to pen this essay where she argues for the USA to “stay the course” and reject “populism, nativism, isolationism, and protectionism”. Condi sees the Chinese as the main opponent of the current global order:

Today’s favorite analogy is the Cold War. The United States again faces an adversary that has global reach and insatiable ambition, with China taking the place of the Soviet Union. This is a particularly attractive comparison, of course, because the United States and its allies won the Cold War. But the current period is not a Cold War redux. It is more dangerous.

China is not the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was self-isolating, preferring autarky to integration, whereas China ended its isolation in the late 1970s. A second difference between the Soviet Union and China is the role of ideology. Under the Brezhnev Doctrine that governed Eastern Europe, an ally had to be a carbon copy of Soviet-style communism. China, by contrast, is largely agnostic about the internal composition of other states. It fiercely defends the primacy and superiority of the Chinese Communist Party but does not insist that others do the equivalent, even if it is happy to support authoritarian states by exporting its surveillance technology and social media services.

The preferred us vs. them in western policy circles is “free market democracies vs. authoritarian regimes”, but Condi concedes that Beijing has thus far shown no desire to export its ideology nor modes of governance. The communists sought world revolution (until they gave up on it), but the Chinese show no desire to Sinicize the globe. This makes the preferred representation of how the camps are divided much less easier to argue and maintain.

More on the Chinese threat:

China’s conventional military modernization is impressive and accelerating. The country now has the largest navy in the world, with over 370 ships and submarines. The growth in China’s nuclear arsenal is also alarming. While the United States and the Soviet Union came to a more or less common understanding of how to maintain the nuclear equilibrium during the Cold War, that was a two-player game. If China’s nuclear modernization continues, the world will face a more complicated, multiplayer scenario—and without the safety net that Moscow and Washington developed.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, the United States suddenly understood further vulnerabilities. The supply chain for everything from pharmacological inputs to rare-earth minerals depended on China. Beijing had taken the lead in industries that the United States once dominated, such as the production of batteries. Access to high-end semiconductors, an industry created by American giants such as Intel, turned out to depend on the security of Taiwan, where 90 percent of advanced chip making takes place.

It is hard to overstate the shock and sense of betrayal that gripped U.S. leaders. U.S. policy toward China was always something of an experiment, with proponents of economic engagement betting that it would induce political reform. For decades, the benefits flowing from the bet seemed to outweigh the downsides. Even if there were problems with intellectual property protection and market access (and there were), Chinese domestic growth fueled international economic growth. China was a hot market, a good place to invest, and a valued supplier of low-cost labor. Supply chains stretched from China across the world. By the time China joined the World Trade Organization, in 2001, the total trade volume between the United States and China had increased roughly fivefold over the previous decade, reaching $120 billion. It seemed inevitable that China would change internally, since economic liberalization and political control were ultimately incompatible. Xi came to power agreeing with this maxim, but not in the way the West had hoped: instead of economic liberalization, he chose political control.

The Chinese famously took a look at Gorbachev’s reforms and concluded that economic liberalization was necessary, but that political liberalization would be a death sentence for the regime, and possibly for the country as well. The Americans lost their bet.

Trump’s China Policy was kosher:

Not surprisingly, the United States eventually reversed course, beginning with the Trump administration and continuing through the Biden administration. A bipartisan agreement emerged that China’s behavior was unacceptable. As a result, the United States’ technological decoupling from China is now well underway, and a labyrinth of restrictions impedes outbound and inbound investment.

Condi is much, much more dismissive of Russia:

Remarkably, Ukraine, a country that barely has a navy, has successfully challenged Russian naval power and can now move grain along its own coastline. Even more devastating for Putin, his gambit has produced a strategic alignment among Europe, the United States, and much of the rest of the world, leading to extensive sanctions against Russia. It is now an isolated and heavily militarized state.

Putin surely never thought it would turn out this way. Moscow initially predicted Ukraine would fall within days of the invasion. Russian forces were carrying three days’ worth of provisions and dress uniforms for the parade they expected to hold in Kyiv. The embarrassing first year of the war exposed the weaknesses of the Russian armed forces, which turned out to be riddled with corruption and incompetence. But as it has done throughout its history, Russia has stabilized the front, relying on old-fashioned tactics such as human wave attacks, trenches, and land mines. The incremental way in which the United States and its allies supplied weapons to Ukraine—first debating whether to send tanks, then doing so, and so on—gave Moscow breathing room to mobilize its defense industrial base and throw its huge manpower advantage at the Ukrainians.

Still, the economic toll will haunt Moscow for years to come. An estimated one million Russians fled their country in response to Putin’s war, many of them young and well educated. Russia’s oil and gas industry has been crippled by the loss of important markets and the withdrawal of the multinational oil giants BP, Exxon, and Shell. Russia’s talented central banker, Elvira Nabiullina, has covered up many of the economy’s vulnerabilities, walking a tightrope without access to the $300 billion in frozen Russian assets held in the West, and China has stepped in to take off some of the pressure. But the cracks in the Russian economy are showing. According to a report commissioned for Gazprom, the majority-state-owned energy giant, the company’s revenue will stay below its pre-war level for at least ten years thanks to the effects of the invasion.

The erosion the present International Order:

Today’s international system is not yet a throwback to the early twentieth century. The death of globalization is often overstated, but the rush to pursue onshoring, near-shoring, and “friend shoring,” largely in reaction to China, does portend a weakening of integration. The United States has been largely absent from negotiations on trade for almost a decade now. It’s hard to recall the last time that an American politician gave a spirited defense of free trade. The new consensus raises the question: Can the aspiration for the freer movement of goods and services survive the United States’ absence from the game?

Globalization will continue in some form. But the sense that it is a positive force has lost steam. Consider the way countries acted in response to 9/11 versus how they acted in response to the pandemic. After 9/11, the world united in tackling terrorism, a problem that almost every country was experiencing in some form. Within a few weeks of the attack, the UN Security Council unanimously passed a resolution allowing the tracking of terrorist financing across borders. Countries quickly harmonized their airport security standards. The United States soon joined with other countries to create the Proliferation Security Initiative, a forum for sharing information on suspicious cargo that would grow to include over 100 member states. Fast-forward to 2020, and the world saw the revenge of the sovereign state. International institutions were compromised, the chief example being the World Health Organization, which had grown too close to China. Travel restrictions, bans on the export of protective gear, and claims on vaccines complicated the road to recovery.

With the growing chasm between the United States and its allies on one side and China and Russia on the other, it is hard to imagine this trend reversing. Economic integration, which after the collapse of the Soviet Union was thought to be a common project for growth and peace, has given way to a zero-sum quest for territory, markets, and innovation. Still, one would hope that humankind has learned from the disastrous consequences of protectionism and isolationism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. So how can it avoid a repeat of history?

What Is To Be Done?

For Condi, it’s “stay the course”. Please note the amount “wishcasting” that is embedded in these arguments:

Today, Russia’s internal contradictions are obvious. Putin has undone 30-plus years of Russian integration into the international economy and relies on a network of opportunistic states that throw crumbs his way to sustain his regime. No one knows how long this shell of Russian greatness can survive, but it can do a lot of harm before it cracks. Resisting and deterring Russian military aggression is essential until it does.

Putin counts on a cowed and poorly informed population, and his regime indoctrinates young people in ways that are reminiscent of the Hitler Youth.

Putin is Hitler, but he is also very weak. At the same time, he is an existential threat to the US-led order. Schrodinger’s Putin.

Condi being bearish on China’s future:

China’s future is by no means as bleak as Russia’s. Yet China, too, has internal contradictions. The country is experiencing a rapid demographic inversion rarely seen outside of war. Births have declined by more than 50 percent since 2016, such that the total fertility rate is approaching 1.0. The one-child policy, put in place in 1979 and brutally enforced for decades, was the kind of mistake that only an authoritarian regime could have made, and now, millions of Chinese men don’t have mates. Since the policy ended in 2016, the state has tried to browbeat women into having children, turning women’s rights into a crusade for childbearing—yet more evidence of the panic in Beijing.

Another contradiction stems from the uneasy coexistence of capitalism and authoritarian communism. Xi has turned out to be a true Marxist. China’s golden age of private sector–led growth has slowed in large part because of the Chinese Communist Party’s anxiety about alternative sources of power. China used to lead the world in online education startups, but in 2021, the government cracked down on them because it could not reliably monitor their content. A once thriving entrepreneurial culture has withered away. China’s aggressive behavior toward foreigners has exposed other contradictions. Xi knows that China needs foreign direct investment, and he courts corporate leaders from across the world. But then, a Western firm’s offices are raided or one of its Chinese employees is detained, and, not surprisingly, a trust deficit grows between Beijing and foreign investors.

China is also suffering a trust deficit with its youth. Young Chinese citizens may be proud of their country, but a 20 percent youth unemployment rate has undermined their optimism for the future. Xi’s heavy-handed propagation of “Xi Jinping Thought” turns them off. This has led them to adopt an attitude of what is known colloquially as “lying flat,” a passive-aggressive stance of going along to get along while harboring no loyalty or enthusiasm for the regime. Now is thus not the time to isolate Chinese youth but the time to welcome them to study in the United States. As Nicholas Burns, the U.S. ambassador to China, has noted, a regime that goes out of its way to intimidate its citizens to discourage them from engaging with Americans is not a confident regime. Indeed, it is a signal for the United States to keep pushing for connections to the Chinese people.

The overarching conceit is that both Moscow and Beijing cannot survive unless they adopt free-market western liberalism, and wholly integrate themselves into the US-led global order.

Now, the real “What Is To Be Done?” part:

This strategy will require investment. The United States needs to maintain the defense capabilities sufficient to deny China, Russia, and Iran their strategic goals. The war in Ukraine has revealed weaknesses in the U.S. defense industrial base that must be remedied. Critical reforms need to be made to the defense budgeting process, which is inadequate to this task. Congress must strive to enhance the Defense Department’s long-term strategic planning process, as well as its ability to adapt to evolving threats. The Pentagon should also work with Congress to gain greater efficiencies from the amount it already spends. Costs can be reduced in part by speeding up the Pentagon’s slow procurement and acquisition processes so that the military can better harness the remarkable technology coming out of the private sector. Beyond military capabilities, the United States must rebuild the other elements of its diplomatic toolkit—such as information operations—that have eroded since the Cold War.

The United States and other democracies must win the technological arms race, since in the future, transformative technologies will be the most important source of national power. The debate about the balance between regulation and innovation is just beginning. But while the possible downsides should be acknowledged, ultimately it is more important to unleash these technologies’ potential for societal good and national security. Chinese progress can be slowed but not stopped, and the United States will have to run fast and hard to win this race. Democracies will investigate these technologies, call congressional hearings about them, and debate their impact openly. Authoritarians will not. For this reason, among many others, authoritarians must not triumph.

Condi identifies the enemy at home:

The new Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—populism, nativism, isolationism, and protectionism—tend to ride together, and they are challenging the political center. Only the United States can counter their advance and resist the temptation to go back to the future. But generating support for an internationalist foreign policy requires a president to paint a vivid picture of what that world would be like without an active United States. In such a world, an emboldened Putin and Xi, having defeated Ukraine, would move on to their next conquest. Iran would celebrate the United States’ withdrawal from the Middle East and sustain its illegitimate regime by external conquest through its proxies. Hamas and Hezbollah would launch more wars, and hopes that Gulf Arab states would normalize relations with Israel would be dashed. The international economy would be weaker, sapping U.S. growth.

Condi ends with:

The future will be determined by the alliance of democratic, free-market states or it will be determined by the revisionist powers, harking back to a day of territorial conquest abroad and authoritarian practices at home.

This leaves us with the question that was asked back in 2016: What’s in it for regular Americans?

If you think that US media is bad, you should check out just how awful their German colleagues are. Their media is filled to the brim with daily hysteria about the Russians, Nazis, fascists, and so on. Every single day is a struggle to survive against these existential threats.

To the mainstream German media, a conservative Christian Democrat (the kind that ruled much of Western Europe during the Cold War) like Viktor Orban is a fascist in disguise. To the mainstream German media, a statist centrist like Vladimir Putin is Hitler without the disguise. A 90s Clinton Liberal like Donald Trump is both.

Thankfully, Der Spiegel reached out to writers and researchers who specialize in fascism to tell us that all of the above are fascists, and some are Nazis too:

The reversion to fascism is a deep-seated fear of modern democratic societies. Yet while it long seemed rather unlikely and unimaginable, it has now begun to look like a serious threat. Vladimir Putin’s imperial ambitions in Russia. Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalism in India. The election victory of Giorgia Meloni in Italy. Marine Le Pen’s strategy of normalizing right-wing extremism in France. Javier Milei’s victory in Argentina. Viktor Orbán’s autocratic domination of Hungary. The comebacks of the far-right FPÖ party in Austria and of Geert Wilders in the Netherlands. Germany’s AfD. Nayib Bukele’s autocratic regime in El Salvador, which is largely under the radar despite being astoundingly single-minded, even using the threat of armed violence to push laws through parliament. Then there is the possibility of a second Trump administration, with fears that he could go even farther in a second term than he did during his first. And the attacks on migrant hostels in Britain. The neo-Nazi demonstration in Bautzen. The pandemic. The war in Ukraine. The inflation.

Meloni, Modi, Milei, Wilders, Bukele….all are suspected of crypto-fascism here.

Trump? “Fascist”, says neo-conservative Robert Kagan:

In May 2016, Donald Trump emerged as the last Republican standing following the primaries, and the world was still a bit perplexed and rather concerned when the historian Robert Kagan published an article in the Washington Post under the headline "This is how fascism comes to America.”

The piece was one of the first in the U.S. to articulate concerns that Trump is a fascist. It received significant attention around the world and DER SPIEGEL published the article as well. It was an attention-grabbing moment: What if Kagan is right? Indeed, it isn’t inaccurate to say that Kagan reignited the fascism debate with his essay. Interestingly, it was the same Robert Kagan who had spent years as an influential member of the Republican Party and was seen as one of the thought leaders for the neocons during the administration of George W. Bush.

The article has aged well. Its characterization of Trump as a "strongman.” It’s description of his deft use of fear, hatred and anger. "This is how fascism comes to America, not with jackboots and salutes,” Kagan wrote, "but with a television huckster, a phony billionaire, a textbook egomaniac 'tapping into’ popular resentments and insecurities, and with an entire national political party – out of ambition or blind party loyalty, or simply out of fear – falling into line behind him.”

Jason Stanley, the Jacob Urowsky Professor of Philosophy at Yale University, says that fascism has already come to America:

Six years ago, Stanley published a book in the U.S. called "How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them.” The German translation only appeared two months ago, a source of annoyance for Stanley. He also has German citizenship and says that he loves the country despite everything.

So how does fascism work? Modern-day fascism, Stanley writes, is a cult of the leader in which that leader promises rebirth to a disgraced country. Disgraced because immigrants, leftists, liberals, minorities, homosexuals and women have taken over the media, the schools and cultural institutions. Fascist regimes, Stanley argues, begin as social and political movements and parties – and they tend to be elected rather than overthrowing existing governments.

Timothy Snyder says that both Trump AND Putin are fascists:

Timothy Snyder speaks thoughtfully and quietly, but with plenty of confidence. Putin is a fascist. Trump is a fascist. The difference: One holds power. The other does not. Not yet.

"The problem with fascism,” Snyder says, "is that it’s not a presence in the way we want it to be. We want political doctrines to have clear definitions. We don’t want them to be paradoxical or dialectical.” Still, he says, fascism is an important category when it comes to understanding both history and the present, because it makes differences visible.

Austrian Political Scientist Natascha Strobl says that fascists are now everywhere:

But this kind of violence can be seen everywhere, says the Austrian political scientist Natascha Strobl. It merely manifests itself differently than it did in the 1920s, when, early on in the fascist movement in northern Italy, gangs of thugs were going from village to village attacking farmer organizations and the offices of the socialist party, killing people and burning homes to the ground. Today, says Strobl, violence is primarily limited to the internet. "And it is,” says Strobl, "just as real. The people who perpetrate it believe they are involved in a global culture war, a struggle that knows no boundaries. An ideological civil war against all kinds of chimeras, such as 'cultural Marxism’ or the 'Great Replacement.’”

For Bulgarian think-tanker Ivan Krastev, AfD is a fascist organization:

It is all rather perplexing. Back in Berlin, Ivan Krastev makes one of his Krastevian jokes. An American judge, he relates, once said that he may not be able to define pornography, "but I know it when I see it.” The reverse is true with fascism, says Krastev: It is simple to define, but difficult to recognize when you see it.

The "F-word.” F as in fascism or F as in "Fuck you.” It is permissible, as a court in Meiningen ruled, to refer to Höcke as a fascist. The question remains, though, what doing so actually achieves.

So there you have it: anyone to the immediate right of 2024 liberal democracy is a fascist.

Mexico’s outgoing President Obrador is planning on making significant changes to the Mexican Constitution before he leaves office. These proposed changes will greatly impact not just the judicial system, but the mining and energy sectors as well.

Both the USA and Canada are crying “foul”, but that has not dissuaded Obrador from pursuing these reforms:

Just a week ago, we wagered that the US and Canadian embassies would soon begin piling pressure on Mexico as the outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO) seeks to pass sweeping constitutional reforms to its mining laws, energy laws and judicial system, among other things, in his last month in office. Just two days later, the US Ambassador to Mexico, Ken Salazar, sent a communique warning that the proposed judicial reforms could have serious consequences for the US’ trade relations with its biggest trade partner:

Based on my lifelong experience supporting the rule of law, I believe popular direct election of judges is a major risk to the functioning of Mexico’s democracy. Any judicial reform should have the right kinds of safeguards that will ensure the judicial branch will be strengthened and not subject to the corruption of politics.

I also think that the debate over the direct election of judges in these times, as well as the fierce politics if the elections for judges in 2025 and 2027 were to be approved, will threaten the historic trade relationship we have built, which relies on investors’ confidence in Mexico’s legal framework. Direct elections would also make it easier for cartels and other bad actors to take advantage of politically motivated and inexperienced judges…

We understand the importance of Mexico’s fight against judicial corruption. But direct political election of judges, in my view, would not address judicial corruption nor would it strengthen the judicial branch of government. It would also weaken the efforts to make North American economic integration a reality and would create turbulence as the debate over direct election will continue over the next several years.

The judicial system is the easiest point of entry for countries like the USA to meddle in the affairs of its friends (and some of its enemies too).

Canada joins the fray:

It didn’t take long for the Canadian Ambassador, Graham C Clark, to join the scrum, warning that Canadian investors — primarily, of course, the mining companies that dominate Mexico’s mining sector and which now face tougher regulations following Mexico’s mining reforms last year — had also expressed concerns about Mexico’s judicial reform.

“I heard these concerns this morning. So, the only thing I’m doing is listening to what our investors are saying about it and there’s concern,” Clark said, adding that the proposed judicial reforms may affect the “bond of trust” between investors and the Government of Mexico. From Forbes Mexico:

“An investment is a sign of confidence. I’m going to invest in your country, I’m going to, I don’t know, build a factory or invest in a Mexican company,” the diplomat added.

However, the ambassador clarified that his “interest is to convey the concerns of the Canadian private sector” without intervening in Mexico’s affairs.

“As a diplomat, I am very sensitive to any comment that could be seen as interference in Mexico’s affairs and it is certainly not my goal,” Clark said.

Yet interfering in Mexico’s affairs is exactly what Clark and Salazar are doing. And AMLO is acutely aware of this, as, it seems, are many Mexicans. After all, this is not the first time Salazar has meddled directly in Mexico’s domestic affairs. In 2022, Salazar — a long-serving oil and gas lobbyist with close ties to the Clintons — lectured Mexico on renewable energy as the AMLO government sought to pass an energy reform package aimed at restoring a strong role for the state in Mexico’s energy and electricity sectors.

On the proposed reforms:

The AMLO government’s “Plan-C” judicial reform proposals seek to radically reconfigure the way Mexico’s justice system works. Most controversially, judges and magistrates at all levels of the system will no longer be appointed but instead be elected by local citizens. Those elections will be taking place in 2025 and 2027, and sitting judges will have to win the people’s vote if they want to continue working. New institutions will be created to regulate procedures as well as combat the widespread corruption that has plagued Mexican justice for many decades.

This, insists the AMLO government, is all necessary because two of the main structural causes of corruption, impunity and lack of justice in Mexico are: a) the absence of true judicial independence of the institutions charged with delivering justice; and b) the ever widening gap between Mexican society and the judicial authorities that oversee the legal processes at all levels of the system, from the local and district courts to Mexico’s Supreme Court.

There is some truth to this. And making judges electorally accountable may go some way to remedying these problems, but it also poses a threat to judicial independence and impartiality, of which there is already scant supply. As some critics have argued, with AMLO’s Morena party already dominating both the executive and the legislative, there is a danger that it will end up taking control of all three branches of government — just like the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, that held uninterrupted power in the country for 71 years (1929-2000).

While these risks may exist, it is also true that the AMLO government has every right to pursue these reforms, has the support of roughly two-thirds of the Mexican public in doing so, and is following established legal procedures. Put simply, it is doing nothing outside of the law. It is also true that, whatever the Washington Post may claim, Mexico’s judicial reforms are a strictly domestic issue and should be of no business to the US or Canadian governments.

The Mexican reaction:

In his speech on Friday, AMLO also provided some historical background to US meddling in Mexican and Latin American affairs. Like Vladimir Putin, AMLO has a penchant for delving deep into the past to explain current realities:

For many years… the United States has applied an interventionist policy throughout America, ever since it established the Monroe Doctrine…

For a long time Washington set the political agenda of countries on this continent. They imposed and removed presidents at their whim, they invaded countries, created new countries and new protectorates… We were invaded twice… The first time was the War of Intervention of 1847-8, which robbed us of half of our territory. Nine states of the American Union belonged to Mexico.

It was very sad. Imagine: on September 15, the [US troops] took Mexico City and hung the stars and stripes from here, the National Palace. Then, in 1914, they invaded us again, this time in Veracruz. For seven months they occupied our territory.

[T]hen they created a different strategy that was more subtle but highly effective. They began opening up US universities to young, ambitious Mexicans to educate them there… We have evidence of this: [T]hen-President Wilson was told by his secretary of state [Robert Lansing] that it was no longer necessary to invade Mexico or shoot a single bullet; it was just a question of indoctrinating young ambitious Mexicans at US universities.

And the strategy worked… for a long time. At least three (Mexican) presidents during the neoliberal period were educated in the US… [T]he [US] not only dominated politics here but also imposed the economic agenda. They were the ones who defined the so-called structural reforms, they touted the privatisations that transferred the nation’s assets from the hands of the Mexican people into the hands of private individuals and foreign companies.

So, this neoliberal, anti-people, interventionist policy led us into a terrible crisis, a prolonged economic decline — and the people of Mexico, who are fiercely protective of their traditions and are prepared to fight for justice, for freedom, for independence, and sovereignty, said “basta” [enough] and this new transformation began.

Flagrant US Hypocrisy

The US government’s flagrant hypocrisy is once again on full display in this latest diplomatic spat. As Mexico’s former Foreign Minister (and incoming Economy Minister) Marcelo Ebrard pointed out a few days ago, in 42 out of the US’ 50 states at least some, if not all, of the judges are elected:

Dear Ken: what are you talking about? [said in English]. Of all our partners, the US is the country that elects the most judges. In the US, judges are elected in 42 states of the American Union, and this has been going on for more than a century and a half. Mexico never said: ‘oops, democracy is in danger in the United States.’ No one said that, on the contrary, [the election of judges] strengthened it.

What Ebrard doesn’t mention is that all federal judges in the US, including the supreme court judges, are appointed. By contrast, Mexico is proposing to make all judge and magistrate positions subject to vote. In the case of the Supreme Court, which is the highest judicial authority of the land as well as the ultimate interpreter of the constitution, the concerns are understandable.

Will this solve the corruption problem in Mexico’s judiciary? I highly doubt it. But they do have a right to pursue these reforms.

This SCR is already wayyyyy too long, so I’ll keep this segment very, very short. Joseph Heath asks where all the Western Marxists have gone, and provides the answer at the same time: they all became liberals thanks to John Rawls:

So what happened to all this ferment and excitement, all of the high-powered theory being done under the banner of Western Marxism? It’s the damndest thing, but all of those smart, important Marxists and neo-Marxists, doing all that high-powered work, became liberals. Every single one of the theorists at the core of the analytic Marxism movement – not just Cohen, but Philippe van Parijs, John Roemer, Allen Buchanan, and Jon Elster – as well as inheritors of the Frankfurt School like Habermas, wound up embracing some variant of the view that came to be known as “liberal egalitarianism.” Of course, this was not a capitulation to the old-fashioned “classical liberalism” of the 19th century, it was rather a defection to the style of modern liberalism that found its canonical expression in the work of John Rawls.

Click here to read the rest.

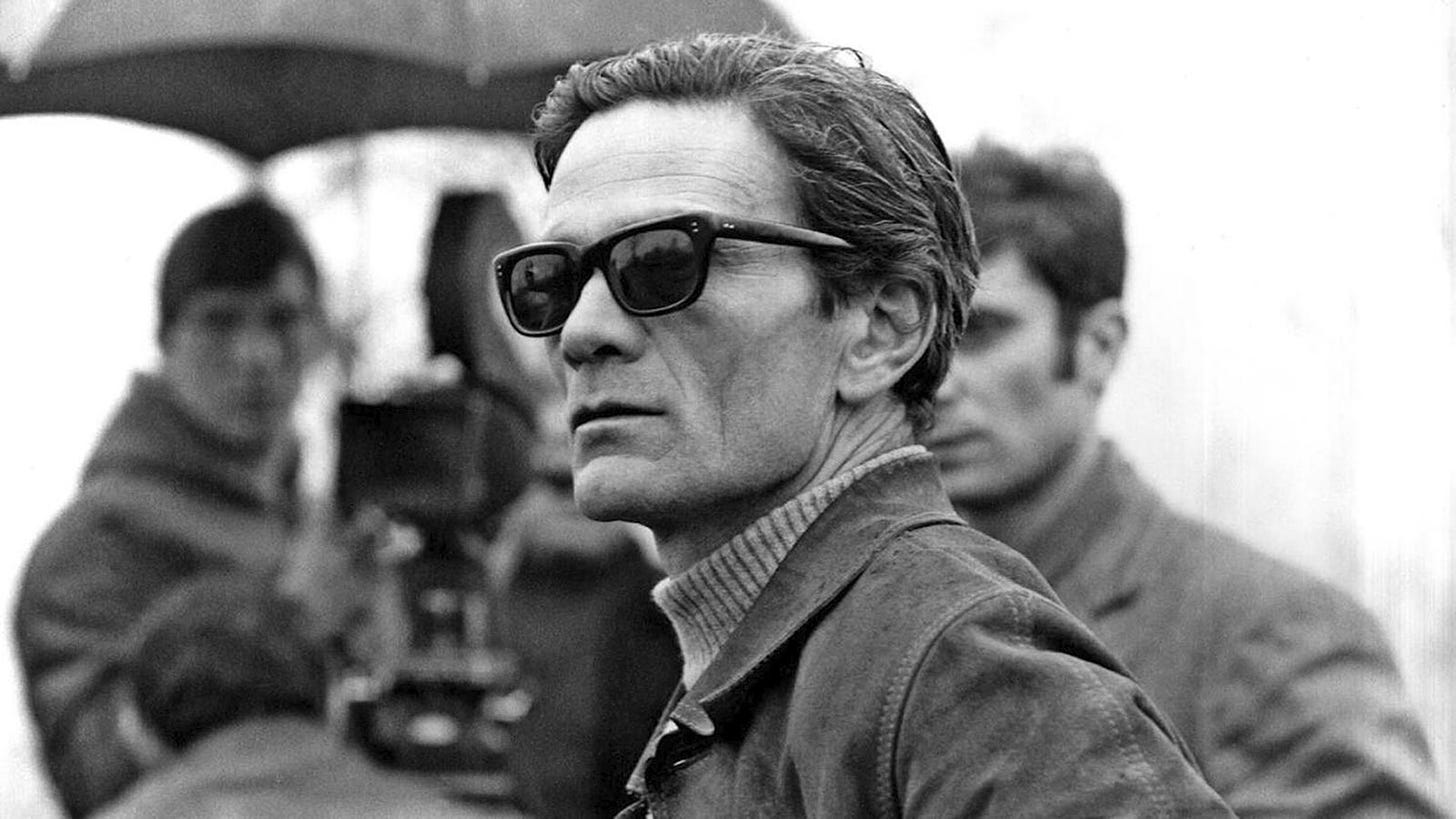

We end this weekend’s SCR with a question: Who really murdered legendary Italian Film Director, Poet, Intellectual, and Iconoclast Pier Paolo Pasolini?

His heart exploded on the night of November 2 1975. His pleas of “Mamma! Mamma!” had done nothing to stop the Alfa Romeo from running over him. When it sped away, his body lay prostrate on a dirt football pitch, under a moonless sky. A frigid wind howled through the surrounding hovels of Ostia and, not far behind, the river Tiber slow-flowed, black and dense like crude, into the sea.

He’d sustained fractures on his breastbone, left jaw, 10 of his ribs and all the fingers on his left hand. His liver was torn, as was the nape of his neck. His slim, muscular arms were speckled with obsidian bruises. A long strip of small, red marks ran over his pale spine, in a symmetrical pattern that matched the Alfa’s tyre treads. The hair on his head was kneaded with earth, blood and oil, his nose flattened to the right, his left ear almost entirely detached.

Even so, all those who saw the body the next morning knew exactly who he was. Onlookers could still make out the elegantly sunken cheeks, the diamond-shaped cheekbones and the long eyebrows, straight and serious under a pensive forehead. They all knew it was Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

And please don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already!

It annoys me when people talk about some secret cynical cabal on Twitter. Reading Condi's essay shows once again these people are telling you exactly what they plan to do, and they're, frankly, fucking crazy and high on their own supply.

>china dominates what the US used to

Well it was probably a bad idea to offshore to Asia wasn't it?

>russia is now an isolated heavily miltarized state

Like that's some kind of victory and not an extremely dangerous situation.

On Trump's foreign policy, I think the best anyone can hope for is he takes down the temperature with China and Russia. If he manages a win of course.