Saturday Commentary and Review #172

"Whole of Society" As a Totalizing Force, Russia "Incapable" of Further War Gains, Saudi "Threat" re: Russian Asset Seizure, Next Washington Consensus, How War on Drunk Driving Was Won

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

Some time ago, I noticed that a general fatigue had taken a place alongside the malaise that was already being felt by many Americans and Canadians. The malaise stemmed from the overdue recognition that their lives were not going to get any better, and that they would have to work harder to just maintain a standard of living that they were already used to.

The fatigue came from a different, but not too distant place; the politicization of everything these past one and a half decades meant that there was no escape the political. Whether sports, video gaming, or even fashion, everything had to be run by the cultural police before it could be deemed “not problematic”. The problem was (and still is) that everything to this type is “problematic”. This would not be a problem at all if this type were not empowered by the powers-that-be, but for some strange reason the cultural police quickly became ubiquitous, and their constant hectoring and lecturing ground most people down to the point where fatigue set in.

Everything became political, so therefore there was nothing that was not political. The fact that sanctions began to be placed against those who dared to buck the new trends in social mores meant that this was a totalizing form of politics. It wasn’t fascism, nor was it communism…..but it was (and is) totalitarianism in a new form all its own. The rise of populism on the right in the West (as this trend is also present in Europe, but is not as thoroughly embedded there as it is in North America) is almost entirely a reaction to this. Freedom and liberty, as traditionally understood in the Anglosphere (i.e. “as long as I don’t harm others, I can do or say what I want”) took a back seat to what they call “equality”, a first step towards the more extreme demand known as “equity”.

Economic precariousness combined with the permanent presence of the Sword of Damocles above your head is a brilliant way to get people to shut up and get with the program. It is very coercive, but it is for the “greater good”, they tell us. What we already see is that it does not convince all, and that it has a negative effect on trust in governing institutions and national elites. The level of control by the managerial elite over the daily lives of its citizens is now at a micro-management one. Everyday, most people have to think carefully before speaking for fear of committing some aggression that could lead to the termination of their employment. They must mouth elite-approved social mores just in order to be able to tread water, as boat rocking is a secular sin. Why would the powers-that-be want to ever give up such a tool of mass control? The people are not to be trusted, which is why this totalizing system must remain in place. Just imagine if it were removed: the dreaded 1990s would return…or something.

Jacob Siegel has written an interesting essay on the concept known as “Whole of Society”, and how it has become a totalizing system:

To make sense of today’s form of American politics, it is necessary to understand a key term. It is not found in standard U.S. civics textbooks, but it is central to the new playbook of power: “whole of society.”

The term was popularized roughly a decade ago by the Obama administration, which liked that its bland, technocratic appearance could be used as cover to erect a mechanism for the government to control public life that can, at best, be called “Soviet-style.” Here’s the simplest definition: “Individuals, civil society and companies shape interactions in society, and their actions can harm or foster integrity in their communities. A whole-of-society approach asserts that as these actors interact with public officials and play a critical role in setting the public agenda and influencing public decisions, they also have a responsibility to promote public integrity.”

In other words, the government enacts policies and then “enlists” corporations, NGOs and even individual citizens to enforce them—creating a 360-degree police force made up of the companies you do business with, the civic organizations that you think make up your communal safety net, even your neighbors. What this looks like in practice is a small group of powerful people using public-private partnerships to silence the Constitution, censor ideas they don’t like, deny their opponents access to banking, credit, the internet, and other public accommodations in a process of continuous surveillance, constantly threatened cancellation, and social control.

The catch:

“The government”—meaning the elected officials visible to the American public who appear to enact the policies that are carried out across the whole of society—is not the ultimate boss. Joe Biden may be the president but, as is now clear, that doesn’t mean he’s in charge of the party.

Siegel writes that the “whole of society” approach arose during Obama’s shift away from the War on Terror to something called “CVE” (Countering Violent Extremism) i.e. the shift away from focusing on Islamist terror towards fighting America’s own citizens who are not with the new political, social, and cultural programs:

But the true lasting legacy of the CVE model was that it justified mass surveillance of the internet and social media platforms as a means to detect and de-radicalize potential extremists. Inherent in the very concept of the “violent extremist,” was a weaponized vagueness. A decade after 9/11, as Americans wearied of the war on terror, it became passé and politically suspicious to talk about jihadism or Islamic terrorism. Instead, the Obama national security establishment insisted that extremist violence was not the result of particular ideologies and therefore more prevalent in certain cultures than in others, but rather its own free-floating ideological contagion. Given these criticisms Obama could have tried to end the war on terror, but he chose not to. Instead, Obama’s nascent party state turned counterterrorism into a whole-of-society progressive cause by redirecting its instruments—most notably mass surveillance—against American citizens and the domestic extremists supposedly lurking in their midst.

A reflection on the 20-year anniversary of Sept. 11 written in 2021 by Nicholas Rasmussen, the former director of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, captures this view. “Particularly with the growing threat to public safety and security posed by domestic violent extremism, it is essential that we move beyond the post-9/11 counterterrorism strategy paradigm that placed the government at the center of most counterterrorism work.” Instead of expecting the government to deal with terrorist threats, Rasmussen advocated for “a much wider, more expansive and inclusive ‘whole-of-society’ approach” that he said should encompass “state and local governments, but also the private sector (to include technology companies), civil society in the form of both individual voices and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and academia.”

Recent examples include:

The whole-of-society trope can be traced from its initial popularization in the context of CVE in 2014-15 to its use as a censorship coordinating mechanism after the rise of Donald Trump initiated a panic over Russian disinformation, then as a call for increased social media clampdowns during COVID, to the present—where it functions as a generic slogan and coordinating mechanism of a party state, one originally built by Obama, and which now operates through the vehicle of the Democratic Party over which he presides.

A “totalizing form of politics”:

Indeed, whole of society is a totalizing form of politics. As the name implies, it discards the traditional separation of powers and demands political participation from corporations, civic groups, and other nonstate actors. Mass surveillance is the backbone of the approach, but it also consolidates a new class of functionaries who all directly or indirectly work for the party’s interests. This is exactly how the party carried out its mass censorship during COVID and the 2020 election: by embedding government officials and party-aligned “experts” from the for-hire world of nonprofit activism, inside the social media platforms. The result, as I chronicled in an investigative essay last year, was the largest campaign of domestic mass surveillance and censorship in American history—often censoring true and time-sensitive information.

To avoid the appearance of totalitarian overreach in such efforts, the party requires an endless supply of causes—emergencies that party officers, with funding from the state, use as pretexts to demand ideological alignment across public and private sector institutions. These causes come in roughly two forms: the urgent existential crisis (examples include COVID and the much-hyped threat of Russian disinformation); and victim groups supposedly in need of the party’s protection.

Jacob’s essay pairs nicely with this essay that I wrote about America’s transformation some three and a half years ago:

There is no escape from a totally politicized society, especially when escapism itself has been politicized.

Last week, Boris Johnson penned an opinion piece in which he offered up a “peace plan” for Ukraine, one that he insisted that Donald Trump could deliver should he re-enter the White House.

The proposal was met with howls of protest, as BoJo suggested that a return to the pre-invasion front line would be one of the conditions for it. The reasons for the anger directed at BoJo was that it was he who was parachuted into Kiev in early 2022 in order to ‘convince’ President Zelensky to not pursue continued talks with the Russians in Turkey aimed at ended the war early on. Two years of an incredible amount of bloodshed and destruction have been spent because BoJo’s message back then was that Ukraine could win the war and get all of its territory back. Perfidious Albion indeed.

On the battlefield, the Russians continue to make some incremental gains, with a potential breakout occurring towards Pokrovsk in Donetsk, a major logistical centre for the UAF. Yet no major breakthrough has occurred. Many pro-Russian analysts will argue that this is by design, as it is a war of attrition, one that cannot work in favour of the heavily-outgunned Ukrainians, and that they will in due time experience a collapse in one or more parts of the front. Others argue that the arrival of more western military aid is now being used to bolster Ukrainian defenses, and that the Russians will not be able to make any more significant gains on the map:

Russia is unlikely to make significant territorial gains in Ukraine in the coming months as its poorly trained forces struggle to break through Ukrainian defenses that are now reinforced with Western munitions, U.S. officials say.

Through the spring and early summer, Russian troops tried to take territory outside the city of Kharkiv and renew a push in eastern Ukraine, to capitalize on their seizure of Avdiivka. Russia has suffered thousands of casualties in the drive while gaining little new territory.

Russia’s problems represent a significant change in the dynamic of the war, which had favored Moscow in recent months. Russian forces continue to inflict pain, but their incremental advances have been slowed by the Ukrainians’ hardened lines.

more:

“Ukrainian forces are stretched thin and face difficult months of fighting ahead, but a major Russian breakthrough is now unlikely,” said Michael Kofman, a senior fellow in the Russia and Eurasia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who recently visited Ukraine.

BTW, a very, very interesting concession made in this NY Times report:

It is that last point that has become the focus of the war, more important even than reclaiming territory. While Ukrainian officials insist they are fighting to get their land back, growing numbers of U.S. officials believe that the war is instead primarily about Ukraine’s future in NATO and the European Union.

We were called “liars” for pointing this out from day one of the war.

Back to the original story:

And deep into the third year of a devastating war, there are real concerns about Ukraine’s ability to keep its infrastructure, including its electrical grid, functioning amid long-range Russian attacks.

But the biggest wild card of all may be U.S. policy toward Ukraine after the presidential election this fall.

While Russia is not in a position to seize large parts of Ukraine, the prospects of Kyiv retaking more land from the invading army are also waning. Prodded by American advisers, Ukraine is focused on building up its defenses and striking deep behind Russian lines.

Eric Ciaramella, a former intelligence official who is now an expert on Ukraine working with Mr. Kofman at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said it had become clear over the past 18 months that neither Russia nor Ukraine “possesses the capabilities to significantly change the battle lines.”

The fear on the pro-Kiev side is that Donald Trump could upset the apple cart:

American officials acknowledge that Russia could make significant headway, if there is a big strategic shift, such as by expanding its military draft and training program.

Their predictions would also be undermined if the U.S. policy toward Ukraine and Russia changed.

Under the Biden administration, the United States has provided military advice, real-time intelligence and billions of dollars in weapons.

Former President Donald J. Trump has promised that if elected, he would begin peace negotiations between Russia and Ukraine. While he has not outlined the peace terms he would seek, a quick negotiation would probably force Ukraine to cede vast swaths of territory and give up its ambitions to join NATO.

Russia has also recently significantly increased the pay for volunteers willing to join the fight, indicating potential problems with recruitment. They are pursuing a punishing tempo in Eastern Ukraine…just how long can they continue it?

Russia’s inability to win the war in Ukraine early on shocked many observers who were taken aback by the light touch that Moscow used to pursue its objectives there.

Just as shocking has been the complete failure of the economic war targeting Russia’s economy. The Rouble has not tanked, Russia’s economy has not collapsed, and most of the world thumbed their noses at US-led demands to sanction Moscow. The punishing sanctions regime against Russia has led to a few boomerang effects, whether they be a stronger Russian industrial capacity, or the de-industrialization hitting parts of Europe, especially Germany. The carrots and sticks aren’t up to their usual tricks, as third party states are reaping windfalls acting as go-betweens for Russia and other states purchasing their exports.

Some western observers have conceded that warfare on the economic front has been a complete disaster, but quite a few western officials feel that this is only due to half-measures; third party countries need to be targeted by secondary sanctions to cut off supplies for the Russian war machine, and frozen Russian assets in western banks should be seized in total and used to help defend Ukraine.

It’s this latter threat that has many foreign capitals (and investors) worried, and led Saudi Arabia to issue a thinly-veiled threat should the G7 try and steal Russia’s assets parked in western financial institutions:

Saudi Arabia privately hinted earlier this year it might sell some European debt holdings if the Group of Seven decided to seize almost $300 billion of Russia’s frozen assets, people familiar with the matter said.

The kingdom’s finance ministry told some G-7 counterparts of its opposition to the idea, which was meant to support Ukraine, with one person describing it as a veiled threat. The Saudis specifically mentioned debt issued by the French treasury, two of the people said.

In May and June, the G-7 was exploring different options regarding the Russian central bank’s funds. The group eventually agreed to tap the profits generated and leave the assets themselves alone despite a US and UK push for allies to consider bolder options, including a direct seizure. Some euro-member nations were against that idea, concerned it could undermine the currency.

Ignore the diplomat language. It was a threat:

Saudi Arabia’s stance likely influenced the reluctance of those countries, said the people, who asked not to be identified to discuss private conversations.

“No such threats were made,” according to a statement sent from the Saudi finance ministry. “Our relation with the G-7 and others is of mutual respect and we continue to discuss all issues that promote global growth and enhance the resilience of the international financial system.”

The kingdom’s holdings of euro and French bonds may amount to tens of billions of euros, but probably aren’t big enough to make a major difference if sold off. European officials were still concerned because other countries might have followed Saudi Arabia’s lead.

One Saudi official said it wasn’t the government’s style to make such threats but that it possibly outlined to G-7 members the eventual consequences of any seizures.

The Saudis realized early on that if they acquiesced to such behaviour, it would set a precedent that could be used against them in the future.

It was unclear, said the people, if Saudi Arabia acted out of self-interest — fearing a seizure would set a precedent that could be used against other countries in future — or in solidarity with Russia. Riyadh and Moscow have maintained close relations since Russia invaded Ukraine and together lead the OPEC+ cartel of oil producers. The Saudi government has also built ties with Ukraine, and President Volodymyr Zelenskiy traveled to the kingdom last month to meet Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Whatever its motive, Saudi Arabia’s move underscores its growing clout on the world stage and the G-7’s difficulty in garnering support from so-called Global South nations for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s aggression.

Under Prince Mohammed, Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, Riyadh has increasingly positioned itself as a diplomatic powerhouse and has said it wants to mediate between Kyiv and Moscow.

The Saudis like the status quo:

Two of the people questioned the credibility of Saudi Arabia’s threat, noting that there had been little movement away from G-7 currencies when the Russian assets were first frozen shortly after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. G-7 members also said there weren’t many reliable alternatives for the Gulf nation to pursue beyond the dollar and euro.

Saudi Arabia sells its oil in dollars, boosting its status as the world’s main reserve currency. Despite widespread speculation that it will switch to other currencies, including China’s yuan, Saudi officials have consistently played down the idea, saying that sticking to the dollar is the best thing for the kingdom’s economy.

“We aren’t interested in de-Dollarization, but please don’t do anything stupid.”

The following essay is a very brainy book review, and might not be for everyone. It tackles the subject of The Washington Consensus, and Jake Sullivan’s announcement for a new consensus to allow the USA to tackle a different world in which key planks of the old consensus no longer hold up. I’ll excerpt some interesting passages here and leave it up to you to read the review in its entirety as it is quite deep:

April 2023 marked the emergence of a “New Washington Consensus,” according to President Biden’s national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, who coined the term in a much discussed speech at the Brookings Institution.1 His argument in brief: events have forced proponents of the original “Washington Consensus”—which he defined as the U.S.-led order that served as the global economy’s foundation since the Second World War—to reexamine its underlying policy assumptions.2 Recent years, Sullivan suggested, “revealed cracks in those foundations,” particularly the global financial crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic, climate disasters, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.3

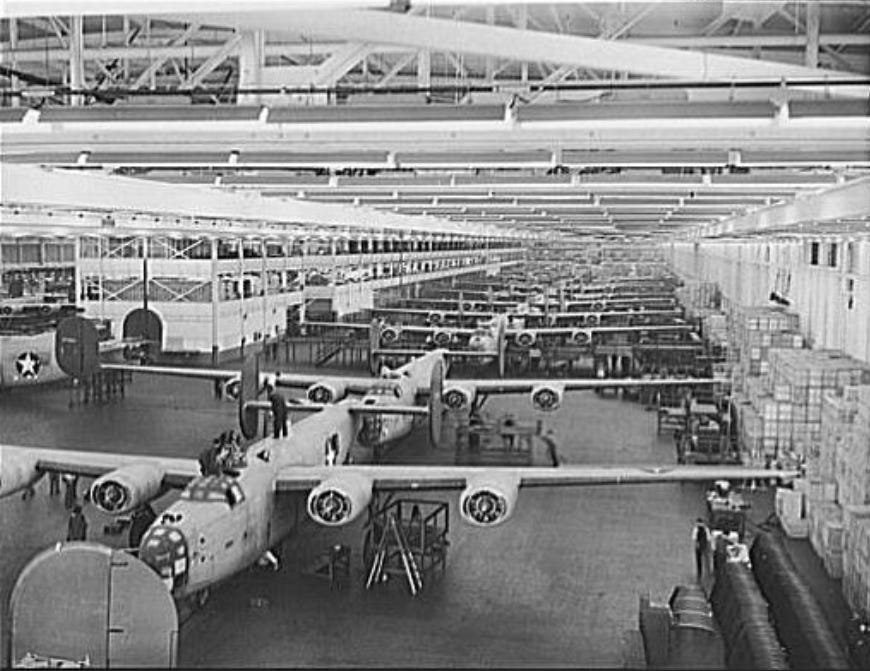

The nascent “new consensus” being championed by the Biden administration, Sullivan continued, represents a rethinking of the failure of four premises of the old order: deindustrialization and supply-chain fragility, which arose due to excessive faith in “oversimplified market efficiency”; the reemergence of great power competition, particularly with China, which has undermined expectations that free trade would lead to political liberalization; the global climate crisis, which was worsened by the notion that green energy required trade-offs with economic growth; and historically high rates of income inequality, which have been exacerbated by overcommitment to trickle-down economic policies.4

This fracturing geoeconomic environment, Sullivan concluded, requires a “modern American industrial strategy” as the core of a “foreign policy for the middle class.”5 These concepts found practical form in the administration’s legislative agenda, the flagship being the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which aims to channel over $500 billion in financing and incentives toward domestic renewable energy projects, especially initiatives related to electric vehicles, leveraging the comparative demand‑side strength of the dollar to reorient green supply chains toward the U.S. market.

For those interested, take a look at my essay on the New Washington Consensus from May of last year:

Back to the review……

Over the course of a thousand pages, Daunton argues that the structure of what became known as the original Washington Consensus was never as rationally conceived as it seems in popular historical imagination. In other words, the “Parthenon style clear pillars” to which Sullivan referred—Bretton Woods, the World Bank, IMF, GATT, and the WTO, among others—always more resembled Gehry’s style: improvised, non-geometric, ad-hoc, a kind of “messy multilateralism.”10 By the end, one is encouraged to read an implied question mark into the title—The Economic Government of the World? As Daunton suggested during his book tour, Sullivan’s clear recognition of this version of history is commendable, as is the transformation of a diagnosis into a prescription: a pragmatic, post-structural global liberalism.11

On the next consensus:

It is possible to understand the “climate crisis” as a relatively inexpensive and capital-light form of accommodation between American corporations and the dominant center-left political class. For now, corporate power speaks the language of “energy transition” (though this may be waning, even rhetorically19). But when it comes to “walking the walk” via active lobbying efforts, American multinationals are much more interested in moving the needle on highly discrete, technical policy issues rather than a generationally significant climate agenda.

What has been described as “quiet politics”—the dominance of under‑the-radar, soft corporate campaigns favoring a stable regulatory environment—has remained essentially unchanged from the Clinton-Bush neoliberal era.20 From this (determinative) corporate perspective, any evidence for the claim that the American political system is experiencing a major “realignment”—something occasionally claimed by reformers on both right and left—seems purely epiphenomenal.

Stay the course?

The American center-left, which for now remains at least rhetorically, but probably also practically, open to Chinese collaboration on its chosen agenda—the climate change project-state—probably will not deviate from its current trajectory for the foreseeable future. In all likelihood, this faction will only adapt the post–Cold War security state to renewed great power competition within the framework of green technology, along with the enforcement of a so-called “small yard, high fence” policy, which largely keeps inter-Pacific trade open with the exception, theoretically, of sensitive national security technologies like advanced semiconductors. Yet even these efforts will likely be hampered by the lack of a true national consensus, which leaves room for the Republican Party to play spoiler.

The much more unsettled GOP commands even less of a mandate (or even an internal consensus) on how to employ the post–Cold War security state. That the security state must somehow be employed, however, stands as perhaps the sole point of policy consensus for the Republicans. What seems even clearer, at least for the present, is that the party will not neatly realign under the green auspices of the IRA or Bidenomics, even as individual legislators will continue to accept green investment in their districts. But what, then, is to ground, as Daunton would put it, the right-of-center’s version of “contestation”?

Three groups to watch:

The Economist, following the European Council on Foreign Relations, suggests three plausible, alternative paths forward, based upon the three extant foreign policy factions within the Republican Party—which are, in a sense, neoliberal mirrors of Schwartz’s post–World War II groupings.21 The Primacists, in some sense heirs to the old Internationalists, are also the contemporary reprise of the 1990s and 2000s neoconservatives. They are, in a word, committed to perpetual American hegemony, largely in the service of American tech multinationals and the finance industry. While some may occasionally gripe about the center-left’s commitment to carbon reduction (largely on fiscal grounds), they remain committed to defending, and indeed expanding, the post–Cold War American defense perimeter. The status of their prime contemporary commitment, however—the war in Ukraine—brings into question not so much the validity of their moral arguments as their material realism. Unless these global hawks depart significantly from their commitment to fiscal conservatism, and engage in a massive expansion of the defense industrial base, it seems difficult to see a clear path forward.

On the other extreme are the Restrainers, whom the Economist equates with historical isolationists. This faction does not have a definitive political economy position and, consequently, represents no discernable corporate coalition. To the extent they articulate a path forward, it usually amounts to “hard decoupling” from the global economy and retreating behind high tariff walls in an attempt to reindustrialize. Even if they enjoy occasional electoral success on thin margins, however, they will find it extremely difficult to govern. Notably, this group is largely in favor of a rollback of the current American security state, leaving it currently—though not indefinitely—the furthest away from commanding a new American political economy consensus. This scenario remains well outside the Overton window, and is completely unpalatable to corporate America.

Straddling these two groups are the Prioritizers, the closest analogue to the old Security Internationalists, who wish to shift the American military force posture from Europe and the Middle East to Asia, which represents over 50 percent (and growing) of global GDP. Thus, under conditions of scarce security resources, this group counsels prioritizing this region as the focus and future of American political economy. For now, ensuring that China’s military cannot achieve regional hegemony by force is this faction’s main priority, but it has yet to reach a definitive consensus on what sort of corporate coalition its desired form of security state might serve. Like the old Security Internationalists, this may provide useful flexibility in negotiation. One could imagine, for example, this faction brokering a deal between Primacists and Restrainers, facilitating a more robust American industrial renaissance based on a limited forward defense posture—spearheaded by weapons exports, chiefly to Japan, the Philippines, South Korea, and Australia, to harden the first island chain’s conventional defense perimeter and revitalize the U.S. defense industrial base—as the core of the Next Washington Consensus. In practical terms, this might find form in legislation modeled on the IRA or the “Farm Bill,” but for weapons exports.

This is interesting stuff, if a bit dense in certain parts.

Click here to read the rest.

We end this weekend’s SCR with a look at how the war on drunk driving was won:

Viewed from the 1960s it might have seemed like ending drunk driving would be impossible. Even in the 1980s, the movement seemed unlikely to succeed and many researchers questioned whether it constituted a social problem at all.

Yet things did change: in 1980, 1,450 fatalities were attributed to drunk driving accidents in the UK. In 2020, there were 220. Road deaths in general declined much more slowly, from around 6,000 in 1980 to 1,500 in 2020. Drunk driving fatalities dropped overall and as a percentage of all road deaths.

The same thing happened in the United States, though not to quite the same extent. In 1980, there were around 28,000 drunk driving deaths there, while in 2020, there were 11,654. Despite this progress, drunk driving remains a substantial public threat, comparable in scale to homicide (of which in 2020 there were 594 in Britain and 21,570 in America).

Of course, many things have happened in the last 40 years that contributed to this reduction. Vehicles are better designed to prioritize life preservation in the event of a collision. Emergency hospital care has improved so that people are more likely to survive serious injuries from car accidents. But, above all, driving while drunk has become stigmatized.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

And please don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already!

Well that Siegel piece was perfectly disturbing. Not because it was at all surprising -- internet surveillance expanded, of course, in perfect conjunction with the so-called Great Awokening, which also kicked off during Obama's second term. Rooting out wrongthink against a totalizing state ideology is no easy feat.

No, what's disturbing is how it came about. Siegel's account dovetails perfectly with both Mike Benz's and Matt Taibbi's expositions on the Twitter files. In Benz's telling, the security state viewed the internet as a convenient disruptor of disfavored regimes abroad, and was perfectly willing to throw gas on the digital fires that stoked outbursts like the Arab Spring. But as the internet gradually facilitated domestic opposition, they became more circumspect. And Taibbi provides examples, such as organizations like the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, which pivoted from profiling jihadis to any and all "extremists" online, interfacing with Twitter and any social media they could sink their hooks into.

If this sounds crazy, good. It is. But it's also not. It occurred via sheer bureaucratic inertia. Washington is at bottom a jobs program for party members. Would CISA and the like, after defeating Al-Queda and ISIS, declare "mission accomplished" and close up shop? Of course not. People have mortgages to pay, after all. The show always goes on.

To tie this into the subsequent essays: Washington has sunken unfathomable energies into Ukraine for the past decade. Why? For its natural resources, naturally. But its gambit is failing. And God knows how many Western firms were leveraged upon the expectation of its success. So once the Russkies finish grinding the AFU into dust and force NATO's capitulation in the conflict, what will 'Ukrainists' find for new employ? A question worth considering, because empires don't wither away; they implode.