Saturday Commentary and Review #169

The Rainbow Nation Fades Out, Ibram X. Kendi Becoming a Liability, A US Cyber Force? Myanmar As Potential Front in New Cold War, Inventions Unknown to the Ancients

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

Being a teen, the issue of South African Apartheid didn’t really fit all that well within the overarching Cold War paradigm. Unlike most other global issues, this one didn’t break down cleanly between the “freedom-loving West” and the “dictatorial, oppressive communist bloc”, as the push to dismantle the regime came from western liberals who were in agreement with the reds.

This slight bit of complexity did not faze most people, as Apartheid was seen as a relic of an older world, one to be consigned to the proverbial dustbin of history. It’s elimination did fit well enough into the Post-Berlin Wall world, one in which freedom and democracy were to reign supreme. This was more than enough reason for almost all people to cheer the release of Nelson Mandela and applaud South Africa’s embrace of western liberal democracy.

In the early 1990s, men once again dared to flirt with utopian ideas, and South Africa’s “Rainbow Nation” was to be its centrepiece: out with authoritarianism, racism, ethnocentrism, etc., and in with multiracialism, multiethnicity, democracy and individual liberty. We could all leave the past where it belonged (in the past) and live in peace and harmony, as democracy would defend it, secure it, and preserve it. South Africa would lead the way, and would in fact teach us westerners how it is to be done.

Oddly enough, South Africa quickly fell off of the radar of mainstream media in the West when it failed to live up to these lofty goals. Rather than living up to the hype of being the “Rainbow Nation”, it instead was quickly mired in the politics of corruption and race, showing itself to be all too human, just like the rest of us. South Africa had failed to immediately resolve its inherent internal tensions, whether they be racial, economic, ethnic, or ideological, and by extension it had failed to deliver its promise to western liberals. “Out of sight, out of mind” became the best practice, replacing the utopianism of the first half of the 1990s.

Granted, a lot of grace was given to South Africa by western media so long as Nelson Mandela remained in office (and even after that), but the failures were plainly evident to see: an explosion in crime and in corruption were its most obvious characteristics, ones that could not be brushed under the carpet. The African National Congress (ANC), the party that would deliver the promise of the Rainbow Nation, was instead shown to be little more than a powerful engine of corruption and patronage. Luckily for the ANC, it was fueled in large part by the legacy of Mandela and the goodwill that he had accumulated over the years while he sat in prison.

The post-Mandela era has not been kind to the ANC (nor to South Africa as a whole), as the party could no longer hide behind his fading legacy, and could no longer cash in on the goodwill that came from it. It could “put up”, and would it not “shut up”. The ANC over time became a lumbering beast, too big to slay, but too slow to destroy its opposition when compared to its nimble youth.

What has the party delivered in its three decades of power? It did help dismantle Apartheid, but it did not deliver economic prosperity and opportunity to all. Instead, it simply swapped out elites where it could, preferring to keep the new ones in house. An inability to tame crime and to keep the national power grid running has turned the country into a bit of a joke, especially when it is lumped into the BRICS group alongside Brazil, Russia, India, and China. Despite its abundance of natural wealth, South Africa has been economically mismanaged.

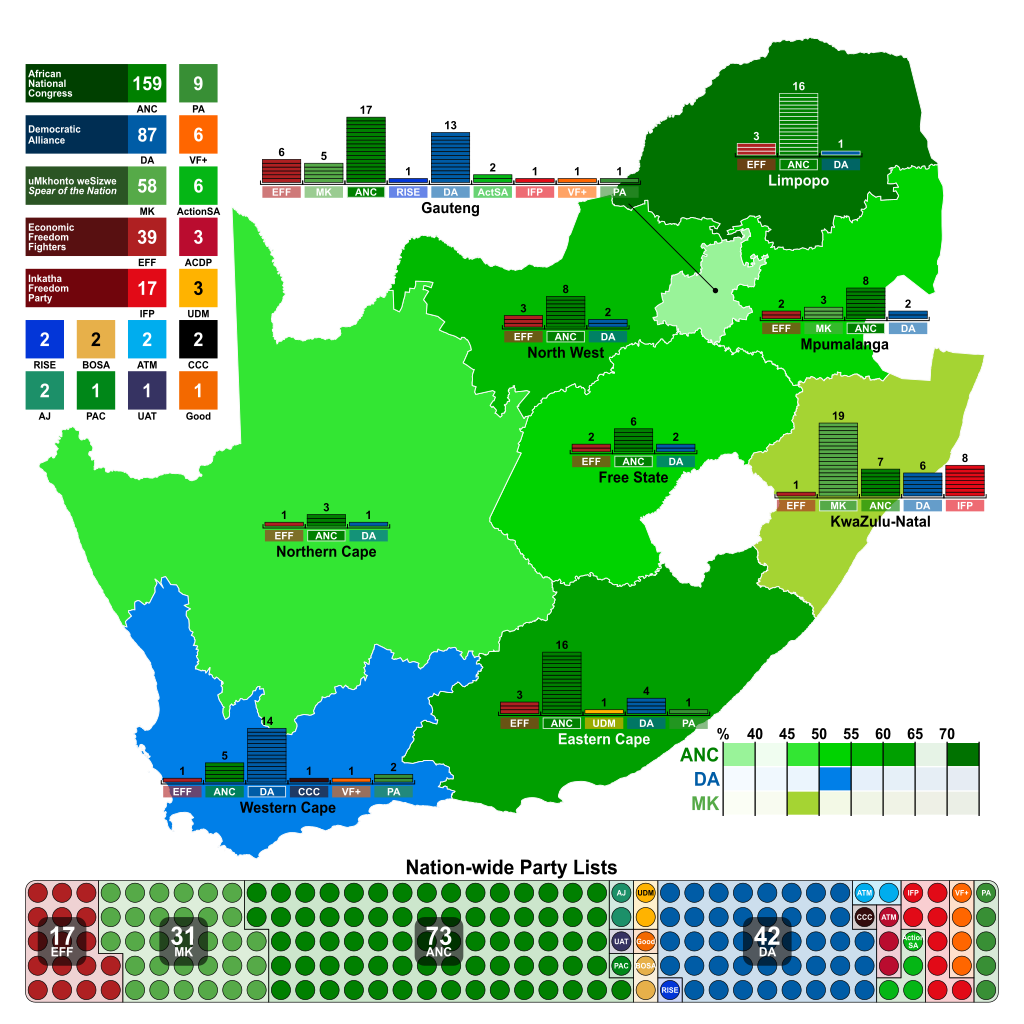

South Africa is an important country to watch for the simple reason that there is so much tinder lying around, ready to be set ablaze. Luckily for South Africans, dire projections of widespread civil strife have not come to pass. Unluckily for South Africans, their national trajectory is headed in the wrong direction. Last week’s national elections saw the ANC lose their parliamentary majority for the first time ever, and the only way to read the results is to conclude that no matter how one may feel about this very corrupt party, it is an ominous sign.

In last week’s South African 2024 general elections, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) saw its gat and the only remaining question is whether the country will as well. From its heady days of 72% support 20 years ago, the party slumped to 40%, losing 70 seats in Parliament and its majority, its seignorial pretentions, and its unrestricted access to the channels of corruption which has funded it and its leaders for 30 years.

Disillusioned ANC supporters stayed home everywhere. The party lost its majority in Gauteng, the country’s economic heartland, and the populous and tumultuous KwaZulu Natal Province. An avenging five-month old radical party, Umkhonto we Sizwe, headed by disgraced and deposed former President Jacob Zuma, swept the polls in the Zulu heartland and emerged the third largest party nationally.

The liberal opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) held the Western Cape and a clutch of small ethnic and regional parties also made incremental progress. Another Zulu-based movement, Inkatha Freedom Front (IFP), increased its share and held its fastnesses north of the Tugela River. The big loser was the urban radical and nativist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) which bled copiously to the even more extreme and anarchic MKP. Socialist and redistributive voters trumped free market ones two-to-one.

One of the big trends that leaps out is that South Africa’s ballooning youth population is voting overwhelmingly for socialist parties, and not the socialist-lite western soc-dem type, either. These are parties committed to economic redistribution, and by the sword if need be.

The author of this piece, a liberal, puts the blame squarely at the feet of the current ANC chief:

The architect of the ANC’s decline is its own President, Cyril Ramaphosa, who was elected with the highest hopes in 2019 that he would be a reformer and an energiser after the eight years of plunder and decay of his predecessor, Jacob Zuma. He was neither, the country deteriorating by virtually every metric possible compared with the country’s halcyon days under former ANC presidents Nelson Mandela and, to a lesser extent, Thabo Mbeki. His weakness in failing to promptly extirpate the Zuma saboteurs from within his ranks years ago, and to lead a reformist national alliance, opened the gap for the extremists such as the EFF and MKP and disheartened even his most ardent supporters. He too has seen his gat.

Few will feel sorry for Ramaphosa. Perhaps fewer still for voters who seem wholly indifferent to either the competence or honesty of their public representatives and routinely vote for their own dispossession by marauding political elites. Such is the allure of tribalism and race.

The choice facing the ANC is between a coalition with economic and political liberals that include the remaining White elites, or with the radical redistributionists of the various Black ethnic groupings:

Will the viviparous ANC, still kingmaker after 30 years despite everything, cast towards its offshoots like the EFF (sprung from the ANC Youth League) or the MKP (the former ANC Zulu diehards) to keep power? Or towards the DA and its liberal-reformist Multi Party Charter? If the former, it brings either 51% or 55% of the electorate and what analyst Dr Frans Cronje calls the Chernobyl Option, keeping power in the short term but sowing the seeds of its own destruction. If the latter, it brings 76% of the electorate and possible economic redemption.

A pre-poll survey by the authoritative Brenthurst Foundation found that South Africans rated weak leadership as a bigger threat than crime, more than three quarters were happy with a coalition Government, and 54% were in favour of a coalition which included liberal parties or ANC and liberal parties. This public expression should guide the ANC but probably will not, which is why it is in the position it is.

Entering into a coalition with the liberals would be seen as a betrayal by many South African Blacks, but the alternative could result in economic collapse.

The liberal author is quite the optimist:

The positive is that despite all past and looming threats, South African democracy is alive and functioning. There was little pre-election violence and a relatively stable, albeit sporadically dysfunctional, electoral process. There are numerous challenges but none that yet appears systemically threatening. The Judiciary intervened when called to defend the process and the media and independent observers were omnipresent and unfettered.

To me, this suggests that even though A LOT has been stolen by rapacious elites, there is still quite a bit more that has not yet been pilfered….not enough to see South Africa drown in civil strife. The loss of a majority for the ANC is a bad omen, though. This election result is a slap in its face.

A concession to human nature:

Vital indicators emerge from these elections. The first is the salience of identitarian or, in its South African context, tribal and ethnic mobilisation, its reality long denied or ignored by white liberals and the black elites. Black South Africans voted overwhelmingly for black parties; whites mostly voted for the DA and the Afrikaner dominated Freedom Front Plus (FF+); mixed-race people deserted the traditional parties to support “brown” and “first nation” parties, the most wildly popular headed by a convicted ex-bank robber who demands the return of the death sentence, and many Asian descended people, when not voting for the DA, voted for tiny local, religious, family and regional parties. With 54 registered parties contesting, there was an embarrassment of choice.

The Rainbow Nation is actually a collection of fiercely tribal groupings that do not look beyond their own in-group.

Some trends to keep an eye on:

Underlying these election results has also been a significant generational aspect. More than two-fifths of the voters were between the age of 18-34. Initial surveys show significant numbers voted for either EFF or MK. To these young voters, the mystique of the ANC holds little allure: the prospects of jobs and a better life do, although, tragically, their political choices last week will certainly defeat their personal hopes. More, the advent of the young disconnected radical, no different from counterparts across the developed world, diminishes the power of the trade unions, historically one of the ANC’s key support pillars but now widely regarded by many unemployed young blacks as anachronistic as the ANC itself. The real face of the ANC thus emerges. It is old, raddled and utterly bereft of ideas.

These elections have consolidated another theme of recent politics in South Africa: localism at both the regional and metropolitan level, a trend which will be hastened by the next round of municipal elections. This process has been underway for some time. As the central State withers, private initiatives move to fill the gaps in education, security, health and most recently in utilities like electricity and water. At the core of this cantonal impulse at municipal level, graced by the name of co-governance, has been the DA and some smaller parties, modest gainers in the elections. The process may promise a sunshine option to the numerous wealthy quasi cantons stretched along the Indian and Atlantic shorelines, but it presages even greater disparities in income and lifestyle chances nationally.

So too at provincial level where two powerful secessionist streams are running, one in the Western Cape, where polls suggest between 46% and 70% of the people wish to break away, and the other in the ever-volatile KwaZulu Natal where a vociferous lobby, the Abantu Batho Congress (ABC), is calling for an autonomous Zulu Kingdom. The extent to which these movements flourish depends on whether the ANC goes into alliance with one of its offspring movements (spurring Western Cape independence) or whether it does not (driving KwaZulu Natal’s simmering revolt).

South Africa is not yet in danger of disintegration in the short term, but the medium term does look a bit ominous.

No one here needs an introduction to Ibram X. Kendi, The Right Side of History Antiracist Fighter Against Racism. He is a cartoon character shoehorned into the role of Pre-Eminent African-American Intellectual after Ta-Nehisi Coates decided to abdicate to pursue his interest in comic books.

What makes Kendi interesting is that he is clearly not fit for this role, and that he has a tendency to put his foot in his mouth over and over again. For me though, what I most appreciate about him is his sincerity. After all, it isn’t every day that you hear a “respected intellectual” call for a new Amendment to the US Constitution where an oversight committee will judge whether any proposed legislation is “racist” or not, and it isn’t every day that respected intellectuals call for the disciplining of public officials for “racism”.

Kendi is back in the news thanks to a very, very long New York Times Magazine profile of him that both defends and criticizes him. The criticism revolves mainly around the failings of his Antiracism Center at Boston U. a subject that we have covered before at this Substack.

Four years have gone by since George Floyd was murdered on the pavement near Cup Foods in Minneapolis, sparking the racial “reckoning” that made Kendi a household name. Many people, Kendi among them, believe that reckoning is long over. State legislatures have pushed through harsh antiprotest measures. Conservative-led campaigns against teaching Black history and against diversity, equity and inclusion programs are underway. Last June, the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions. And Donald Trump is once again the Republican nominee for president, promising to root out “the radical-left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country.”

Kendi has become a prime target of this backlash. Books of his have been banned from schools in some districts, and his name is a kind of profanity among conservatives who believe racism is mostly a problem of the past. Though legions of readers continue to celebrate Kendi as a courageous and groundbreaking thinker, for many others he has become a symbol of everything that’s wrong in racial discourse today. Even many allies in the fight for racial justice dismiss his brand of antiracism as unworkable, wrongheaded or counterproductive. “The vast majority of my critics,” Kendi told me last year, “either haven’t read my work or willfully misrepresent it.”

Criticism of Kendi only grew in September, when he made the “painful decision” to lay off more than half the staff of the research center he runs at Boston University. The Center for Antiracist Research, which Kendi founded during the 2020 protests to tackle “seemingly intractable problems of racial inequity and injustice,” raised an enormous sum of $55 million, and the news of its downsizing led to a storm of questions. False rumors began circulating that Kendi had stolen funds, and the university announced it would investigate after former employees accused him of mismanagement and secrecy.

Kendi’s foot-in-the-mouthism and extremism have led many to question the judgment of making him such a prominent figure in liberal politics. We know this because the New York Times of all places is saying specifically this.

A reminder of his Manichean worldview:

In “How to Be an Antiracist,” his best-known book, Kendi challenges readers to evaluate themselves by their racial impact, by whether their actions advance or impede the cause of racial equality. “There is no neutrality in the racial struggle,” he writes. “The question for each of us is: What side of history will we stand on?” This question evinces Kendi’s confidence that ideas and policies can be dependably sorted into one of two categories: racist or antiracist.

In Kendi’s worldview, everything must be seen through the prism of race and racial politics.

Kendi has been cleared of wrongdoing at his center via an internal audit, but not everyone is happy:

Boston University had recently released the results of its audit, which found “no issues” with how the center’s finances were handled. The center’s problem, Kendi told me, was more banal: Most of its money was in its endowment or restricted to specific uses, and after the high of 2020, donations had crashed. “At our current rate, we were going to run out in two years,” he said. “That was what ultimately led us to feel like we needed to make a major change.” The center’s new model would fund nine-month academic fellowships rather than a large full-time staff. Though inquiries into the center’s grant-management practices and workplace culture were continuing, Kendi was confident that they would absolve him, too. In the media, he’d dismissed the complaints about his leadership as “unfair,” “unfounded,” “vague,” “meanspirited” and an attempt to “settle old scores.”

In the fall, when I began talking to former employees and faculty — most of whom asked for anonymity because they remain at Boston University or signed severance agreements that included nondisparagement language — it was clear that many of them felt caught in a bind. They could already see that the story of the center’s dysfunction was being used to undermine the racial-justice movement, but they were frustrated to watch Kendi play down the problems and cast their concerns as spiteful or even racist. They felt that what they experienced at the center was now playing out in public: Kendi’s tendency to see their constructive feedback as hostile. “He doesn’t trust anybody,” one person told me. “He doesn’t let anyone in.”

Antiracism as a brand:

Kendi and DiAngelo’s talk of confession — antiracism as a kind of conversion experience — inspired many people and disturbed others. By focusing so much on personal growth, critics said, they made it easy for self-help to take the place of organizing, for a conflict over the policing of Black communities, and by extension their material conditions, to become a fight not over policy but over etiquette — which words to use, whether to say “Black Lives Matter” or “All Lives Matter.” Many allies felt that Kendi and DiAngelo were merely helping white people alleviate their guilt.

They also questioned Kendi’s willingness to turn his philosophy into a brand. Following the success of “How to Be an Antiracist,” he released a deck of “antiracist” conversation-starter cards, an “antiracist” journal with prompts for self-reflection and a children’s book, “Antiracist Baby.” Christine Platt, an author and advocate who worked with Kendi at American University, recently co-wrote a novel that features a Kendi-like figure — a “soft-spoken” author named Dr. Braxton Walsh Jr., whose book “Woke Yet?” becomes a viral phenomenon. “White folks post about it on social media all the time,” rants De’Andrea, one of the main characters. “Wake up and get your copy today! Only nineteen ninety-nine plus shipping and handling.”

A criticism leveled at Kendi by the author:

I came to think, after months of talking to Kendi, that this was the key to understanding him — to remember that he is trying to push so hard against that. To shove back the anti-Black stereotypes he documented in “Stamped From the Beginning,” the racist ideas that poisoned his own mind and sense of self-worth. His aim, at every turn, is to blame the policies that create unequal conditions and not the people enduring them. But Kendi is so consumed by combating the racist notion of Black inferiority that some of what he says in response is overstated, circular or uncareful, creating an easy target for his critics and discomfiting his allies. Conservatives were far from the only ones alarmed, for example, by his proposal for a constitutional amendment to appoint a panel of racism “experts” with the power to discipline public officials for “racist ideas.” (Kendi told me he modeled this proposal on European countries like Germany, where the bar for hate speech is much lower.)

Click here to read the rest of this very long profile.

I don’t know about you, but months ago I stopped watching videos of drone attacks in Ukraine. These videos are horrible viewing, and leave me feeling incredibly sad for soldiers targeted by these drones, no matter which side of the battlefield that they are on.

The significant advances in drone warfare are the best example of how conflict continues to morph and change. Although drone warfare is the most obvious (and horrifying) example, it is not on the only one. So-called “cyberwarfare” is advancing just as quickly, and everyone needs to play catch up to ensure their own continued existence.

When we think ‘cyberwarfare’, one of the first examples is of intentional and malicious hacking of things like power grids or financial institutions. These are valid targets in times of war, so fair is fair. But there is another side to cyberwarfare that affects us on the homefront; the so-called “battle against disinformation”. The argument is that opponents will use ‘disinformation’ to insert false news in our domestic media to either confuse us or to get us to diverge with our own governments when it comes to their foreign policy (this is just one example of the argument, of course). This is a difficult sell in times when trust in governing institutions is at an all-time low, as the government is asking us to give them the benefit of the doubt.

This is why the push to create an independent military branch by the USA devoted solely to cyberwar should interest, and worry, all Americans:

The US is moving to establish a new Cyber Force to close emerging cyberspace defense gaps with near-peer rivals Russia and China, both of which are blending cyber and information operations to strategic effect.

Late last month, multiple media outlets reported that the US Congress is considering establishing an independent Cyber Force as part of the 2025 defense authorization bill, a response to long-held concerns about the current cyber defense structure.

An amendment, led by Representative Morgan Luttrell and included in the House Armed Services Committee’s markup, mandates a National Academy of Sciences study on creating the proposed new military branch.

The proposal, which has passed the committee and awaits a full House vote, seeks to address the inadequacies and complexities of the existing US military cyber formations, as highlighted by various studies and analysts.

More:

If approved, the new branch could be established by 2027, following further legislative and administrative procedures. The development underscores the perceived urgent need for a dedicated cyber defense mechanism in the face of escalating global cyber threats.

The proposed Cyber Force aims to streamline the organizational framework for US cyber capabilities, emphasizing a unified recruitment, training and retention framework to harness and elevate cyber expertise in a digital battlespace.

In March 2024, Asia Times discussed the pros and cons of establishing a separate Cyber Force. Proponents argue that current military structures are inadequate for recruiting, training and retaining cyber talent, and that personnel shortages and fragmented approaches are hindering cyber readiness.

Critics argue that a separate Cyber Force may introduce new inefficiencies and that the existing US Cyber Command (CYBERCOM) could suffice with significant restructuring, emphasizing the complex interdependencies of cyberspace with other military domains.

The key portion:

Consequently, he says cyber operations are now pivotal in both military and civilian spheres, illustrating a seamless blend of technological exploitation and psychological influence.

Technological exploitation and psychological influence. This targets not just the opponent, but the domestic population as well.

Why US officials are so worried about the internet:

In a May 2024 Defense One article, Patrick Tucker states that the US has inherent resistance to actively influencing perceptions. This resistance stems from the belief that a nation with elected leadership and a free press should not need to engage in such activities beyond simply presenting the truth.

He notes that this stance has historically confined influence operations to a small segment of the special operations community, limiting its scope and impact.

He also says the digital media landscape has evolved, with individualized streams replacing credible national broadcasts, allowing adversaries to exploit social media to reach potentially billions with tailored messages and undermine trust in Western institutions, including the US military.

As Tucker mentioned, Jason Schenker, chairman of the Futurist Institute, says the subjective nature of reality on social media platforms further complicates the US’s ability to maintain a coherent national identity and counter disinformation.

Additionally, Tucker says domestic political dynamics pose a challenge, as efforts to combat foreign influence campaigns can be misconstrued as partisan politics.

In short, it’s about the restoration of narrative control through techno-psychological warfare against the country’s own citizens.

Ukraine is a proxy war between the USA and Russia. The War in Gaza pits the USA against Iran. I have been keeping a close on eye on other global hot spots, with the Venezuelan-Guyanese border another proxy war in the making, should the Chavistas in Caracas under Maduro do something as stupid as move in on their neighbour.

Myanmar has all the makings of a potential proxy war between the USA and China (and Russia as well). Sharing a border with China, it is too tempting a target for the Americans to ignore, even if their participation is at a minimal level. It makes perfect sense as well if you view the Americans as the Brits of WW2 fighting the Japanese Imperial Army. today are the Chinese Red Army.

By any measure, it would be a stretch to say that the United States is currently engaged in a New Cold War proxy war with China and Russia in Myanmar.

But as the conflict between the State Administration Council (SAC) junta and a proliferating array of ethnic and political resistance armies escalates, the rivalry between the world’s two big blocs could yet determine the outcome of Myanmar’s increasingly vicious civil war.

On one side, the US is supporting the anti-coup National Unity Government (NUG) and by extension its affiliated People’s Defense Forces armed groups scattered across the country. On the other, China and Russia are more clearly, although not always overtly, in the junta’s camp.

With its substantial and geostrategically important investments in Myanmar, China has the biggest great power interest in the war’s direction and outcome.

While Beijing is playing both sides of the war — selling military hardware to the SAC and turning a blind eye to Chinese weaponry ending up in the hands of some of the ethnic resistance armies — it clearly doesn’t want the conflict to spiral out of control to the degree it hurts or threatens its in-country interests.

The US, for its part, appears to have refrained from directly providing the various armed groups fighting the junta with weapons and has confined its support to “non-lethal” aid to the NUG, which notably maintains an office in Washington DC.

If the US sought to escalate the Myanmar war into a New Cold War proxy theater, targeting China’s big-ticket interests in the country would be a logical tactic.

Let’s look at the logic:

If the US wanted to be more overtly involved at the battlefield level, it would need to do so through Thailand, which like China has no interest in stirring instability that could spill over its borders in a bigger way.

Thailand also relies on Myanmar’s natural gas and so has an incentive not to rile the generals through any hint it may be funneling arms to insurgent groups. The US has thus seemingly focused its diplomacy on pressing the Thais to turn a blind eye to the NUG and other exile forces that operate from Thai soil, including in the border town of Mae Sot.

To be sure, the US may still be providing more clandestine aid to the resistance than it publicly acknowledges, including potentially through elements in the Thai military known to be sympathetic with certain ethnic armies. But if so it has not been to a degree or manner that could turn the war or threaten China’s position.

Myanmar’s geostrategic importance to China:

China’s reasons for aspiring to influence, contain and even control Myanmar’s conflict are obvious and many. Myanmar is the only immediate neighbor which provides China with convenient, direct access to the Indian Ocean, bypassing the contested South China Sea and congested Strait of Malacca, which the US could potentially block in a conflict scenario.

Such a connection is vital for the export of Chinese goods to the outside world as well as the importation of fossil fuel from the Middle East and minerals from Africa. That is why China has built oil and gas pipelines from the shores of the Bay of Bengal to its southern province of Yunnan and plans to construct highways and a high-speed rail along the same route.

As part of the plan, Chinese state-owned entities are developing a US$7.3 billion deep-water port at Kyaukphyu on the coast of Myanmar’s Rakhine State and a US$1.3 billion special economic zone (SEZ), which includes an oil and gas terminal.

Those projects are located at the lower end of the 1,700-kilometer China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) connecting Kunming in China’s Yunnan province to the Indian Ocean.

As such, Beijing will do everything in its power to protect its geostrategic interests — and it does not take lightly any attempt by what it considers outsiders to interfere with its long-term plans for Myanmar and the region.

Some history:

Having supported the insurgent Communist Party of Burma (CPB) in the late 1960s and early 1970s, China’s foreign policy changed after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and the subsequent rise of reformist Deng Xiaoping. His new China no longer attempted to export revolution; now it was all about economic development and the establishment of trade with the outside world.

The aftermath of the Myanmar military’s bloody suppression of a pro-democracy uprising in 1988 provided China with the opening it craved. While the West imposed sanctions and boycotts against the junta in Yangon, China began to promote cross-border trade — and in the decade after the massacres, China sold more than US$1.4 billion worth of aircraft, naval vessels, heavy artillery, anti-aircraft guns, and tanks to Myanmar.

China also helped Myanmar upgrade its naval bases along the coast and on islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Chinese-supplied radar systems were installed in some of these bases, and it is reasonable to assume that China’s security services benefited from the resulting intelligence.

But the fiercely nationalistic Myanmar military never felt wholly comfortable with its heavy dependence on China for arms and supplies. The Chinese were treating Myanmar as a client state and many Myanmar army officers could not forget that thousands of their soldiers had been killed by the CPB’s Chinese-supplied guns before that insurgency collapse in 1989.

Burmese balancing:

In order to diversify its sources of procurement, the Myanmar military began to cultivate defense ties with Russia. Myanmar became a lucrative market for the Russian war industry. Myanmar bought Russian-made MiG-29s jet fighters and Mi-35 Hind helicopter gunships, both of which are now being used across the country against the resistance.

By exploiting Chinese double-dealing and Myanmar’s ruling junta’s nationalism, the Americans could, in short, “fuck shit up”:

The New Cold War may not yet be as hot as the previous one was, but it is clear that the Americans and their allies are building a bulwark against China across Asia, seen overtly in the AUKUS, Quad and new Squad multilateral security arrangements geared to contain Beijing’s rise.

But the construction of a huge new US consulate general in Chiang Mai and financial support for the pro-democracy forces inside Myanmar are also part of this larger China, and by bloc association, Russia containment strategy.

There is still a long way to go before we see the return to the open Cold War proxy confrontations of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. But conflict-ridden Myanmar may well once again find itself in the eye of a new geopolitical storm over which it will have little or no control.

I’m keeping an eye on Myanmar and will do so for years to come.

We end this weekend’s SCR with a post about inventions unknown to the ancients, and compiled in an 16th century book on the same topic:

One of these is a list from 1715 of inventions that had never been known to the ancient Greeks or Romans. It was appended to an English translation of a work by the Italian historian Guido Panciroli called The History of Many Memorable Things Lost, originally written in Italian but first published by one of his students in Latin in 1599 after Panciroli had died. Panciroli himself had already noted a few things they believed to have been unknown to the Ancients. From the vantage point of the 1590s these included the better-known achievements of the moderns like moveable-type printing, gunpowder, stirrups, spectacles, weight-driven clocks, the magnetic compass, and the discovery of the New World. But he also included (though not always accurately):

The Chinese invention of porcelain — which he erroneously believed to be “a compound of gypsum, beaten eggs, and the shells of lobsters” all mashed up and then buried for at least eighty years

The discovery of bezoar stones, used against venoms and poisons, which he said were mined in the Maghreb

Refined sugar, including the art “arrived to such perfection” of candying nuts and spices

Alchemical discoveries like gilding brass, the whitening of sapphires, improved alloys of tin, the use of cupels for assaying metals, and aqua fortis (nitric acid) with which to separate gold from either brass or silver.

Distillation, especially of various oils and tinctures of herbs and spices for medicines, as well as aqua vitae or ‘waters of life’ like whisky

Cryptographical methods, which he judged to have become more sophisticated since ancient times. The later translator agreed, noting how during the English Civil Wars anyone who was anyone used ciphers, many of which challenged even the master code-breaker Dr John Wallis, Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford.

The seventh-century Byzantine invention of “Greek fire”.

Silk-making, brought to Europe in the sixth century, along with silk-based variants like velvets and satins.

He also included jousting, falconry, watermills, saddles, and the eating of fish roe dishes like caviar and bottarga. And the use of mana as a medicine. The student who published Panciroli’s work, who added some of his own commentary, was a little sceptical of some of these.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button at the top or the bottom of this page to like this entry, and use the share and/or res-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you to do so. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top or bottom of this page to like this entry. Use the share and/or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

And please don't forget to subscribe if you haven't done so already!

Funny that the cyber warfare people are afraid of the Internet.

They had total control of TV, radio, and newspapers in an Orwellian fashion for decades. They thought they could control the Internet and we saw how much they tried the last few years!

Here's an interesting article that makes good points about the end of this authoritarian control because they had to be so extreme about covid, the mask of sanity slipped off and we saw how our politicians are just puppets to big interests.

https://realleft.substack.com/p/no-conspiracies-please-were-reality

"As traumatic transformations go, the covid operation is up there with industrialisation and de-industrialisation, and for time compression it is out on its own."

"And as for the rabbit hole trope – well, I don't think we’re going down the rabbit hole at all. We’re climbing out of it into the light."

Yes! I call this the sequel to 1984. The party lost the trust of the masses. Look how they're trying to make us scared of war with China and Russia.... Meanwhile the oil and money still flows.

What a joke.

To use the Alice in Wonderland analogy, we were hallucinating in wonderland and now waking to real land which is much less insane.