Saturday Commentary and Review #151

The Coming Competency Crisis, How to Decolonize Britain, Europe's Political Stupor, Who is Siding With Israel at The Hague?, All the James Bond Movies Ranked

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

Request: Please hit the like button at the top or bottom of the page. The more likes these entries get, the more attractive it is to new readers. This place continues to grow, and I would like to maintain the momentum. Just click the button at the top like this:

Americans will often point to a decline in national infrastructure when disagreeing with my assessment that the USA is nowhere near a state of collapse for the time being. Yes, decay in infrastructure is plainly evident to anyone with two working eyes, but the USA’s enormous head start against China makes this decay tolerable……for now.

When cornered by others as to how long this state of affairs can last, I usually say “twenty years or so”. The USA can spend 20 years experimenting with all sorts of counterintuitive schemes, while still retaining its global dominance. The breaking point will come when the bottom line is so negatively affected that US financial dominance over the globe (via control of global bodies like the IMF/World Bank, or especially the end of the greenback as the global currency reserve) is close to ending.

The experimentation that I am referring to is ideological in nature and stems from the drive against “anti-discrimination” that was codified in the US Civil Rights Act of 1964. Christopher Caldwell has referred to it as “the USA’s Second Constitution”, in order to underline just how revolutionary an impact the changes stemming from this act have had on the USA ever since. This ideological adoption continues to pick up momentum, as it has captured institution after institution. What we refer to as “wokeness” today has its legally applicable roots in these laws. One element of this has been the adoption and institutionalization of “DEI” (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) programs in US academia, governance, and the corporate world.

DEI is a direct attack on meritocracy, as DEI mandates that diversity must always take precedence over it in decision-making regarding hiring. This is leading to alarms being rung throughout the professional world in the USA, arguing that an erosion of the meritocratic system is leading to a “crisis of competency” at home, and quickly eroding the USA’s ability to project power abroad, as its rivals play catch up by adhering to meritocratic principles and standards. In this excellent article, Harold Robertson warns Americans that “complex systems won’t survive the competency crisis” that DEI has unleashed:

The core issue is that changing political mores have established the systematic promotion of the unqualified and sidelining of the competent. This has continually weakened our society’s ability to manage modern systems. At its inception, it represented a break from the trend of the 1920s to the 1960s, when the direct meritocratic evaluation of competence became the norm across vast swaths of American society.

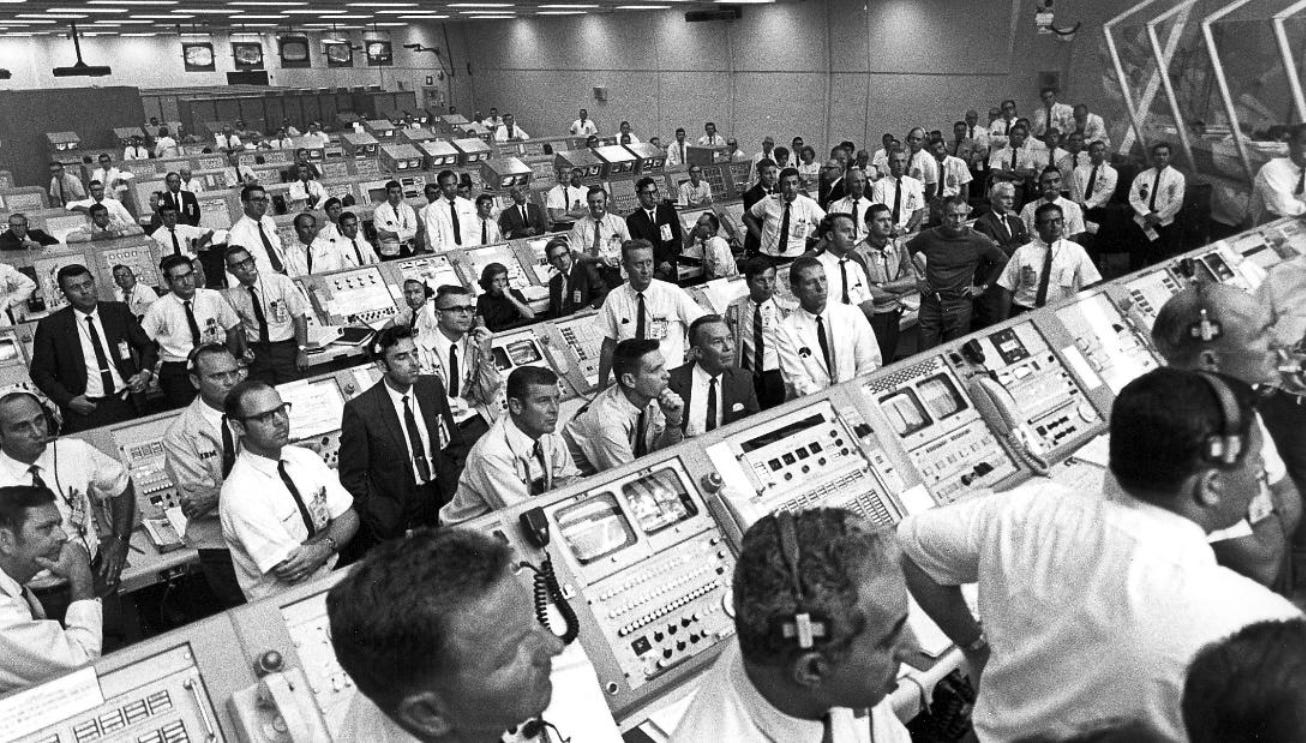

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the idea that individuals should be systematically evaluated and selected based on their ability rather than wealth, class, or political connections, led to significant changes in selection techniques at all levels of American society. The Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) revolutionized college admissions by allowing elite universities to find and recruit talented students from beyond the boarding schools of New England. Following the adoption of the SAT, aptitude tests such as Wonderlic (1936), Graduate Record Examination (1936), Army General Classification Test (1941), and Law School Admission Test (1948) swept the United States. Spurred on by the demands of two world wars, this system of institutional management electrified the Tennessee Valley, created the first atom bomb, invented the transistor, and put a man on the moon.

By the 1960s, the systematic selection for competence came into direct conflict with the political imperatives of the civil rights movement. During the period from 1961 to 1972, a series of Supreme Court rulings, executive orders, and laws—most critically, the Civil Rights Act of 1964—put meritocracy and the new political imperative of protected-group diversity on a collision course. Administrative law judges have accepted statistically observable disparities in outcomes between groups as prima facie evidence of illegal discrimination. The result has been clear: any time meritocracy and diversity come into direct conflict, diversity must take priority.

The resulting norms have steadily eroded institutional competency, causing America’s complex systems to fail with increasing regularity. In the language of a systems theorist, by decreasing the competency of the actors within the system, formerly stable systems have begun to experience normal accidents at a rate that is faster than the system can adapt. The prognosis is harsh but clear: either selection for competence will return or America will experience devolution to more primitive forms of civilization and loss of geopolitical power.

This argument makes quite a lot of sense, especially when you factor in how interlocked these systems are with one another, and how a collapse in competency in one will have cascading effects for the whole.

From meritocracy to diversity:

The first domino to fall as civil rights-era policies took effect was the quantitative evaluation of competency by employers using straightforward cognitive batteries. While some tests are still legally used in hiring today, several high-profile enforcement actions against employers caused a wholesale change in the tools customarily usable by employers to screen for ability.

After the early 1970s, employers responded by shifting from directly testing for ability to using the next best thing: a degree from a highly-selective university. By pushing the selection challenge to the college admissions offices, selective employers did two things: they reduced their risk of lawsuits and they turned the U.S. college application process into a high-stakes war of all against all. Admission to Harvard would be a golden ticket to join the professional managerial class, while mere admission to a state school could mean a struggle to remain in the middle class.

and

This outsourcing did not stave off the ideological change for long. Within the system of political imperatives now dominant in all major U.S. organizations, diversity must be prioritized even if there is a price in competency. The definition of diversity varies by industry and geography. In elite universities, diversity means black, indigenous, or Hispanic. In California, Indian women are diverse but Indian men are not. When selecting corporate board members, diversity means “anyone who is not a straight white man.” The legally protected and politically enforced nature of this imperative renders an open dialogue nearly impossible.

However diversity itself is defined, most policy on the matter is based on a simple premise: since all groups are identical in talent, any unbiased process must produce the same group proportions as the general population, and therefore, processes that produce disproportionate outcomes must be biased. Prestigious journals like Harvard Business Review are the first to summarize and parrot these views, which then flow down to reporting by mass media organizations like Bloomberg Businessweek. Soon, it joins McKinsey’s “best practices” list and becomes instantiated in corporate policies.

You want the best doctor to treat you and your loved ones, but the system that is in place might instead offer you up a doctor who is nowhere near as good as you would be able to get in a meritocratic system (defenders of DEI will argue that a capitalist system will deny those without financial resources this ability anyway).

CEOs push diversity policies primarily to please board members and increase their status. Human Resources (HR) professionals push diversity policies primarily to avoid anti-discrimination lawsuits. Business development teams push diversity to win additional business from diversity-sensitive clients (e.g. government agencies). Employee Resource Groups (ERGs), such as the Black Googler Network, push diversity to help their in-group in hiring and promotion decisions.

These programs are incentivized for several reasons, as we see above. Once the bottom line is impacted, they will be on the chopping block….provided that the laws can be changed to ensure that they aren’t targeted for prosecution, and provided that the culture hasn’t shifted too much by this point in time.

The preference for diversity:

The preference for diversity at the college faculty level is similarly strong. Jessica Nordell’s End of Bias: A Beginning heralded MIT’s efforts to increase the gender diversity of its engineering department: “When applications came in, the Dean of Engineering personally reviewed every one from a woman. If departments turned down a good candidate, they had to explain why.”

When this was not enough, MIT increased its gender diversity by simply offering jobs to previously rejected female candidates. While no university will admit to letting standards slip for the sake of diversity, no one has offered a serious argument why the new processes produce higher or even equivalent quality faculty as opposed to simply more diverse faculty. The extreme preference for diversity in academia today explains much of the phenomenon of professors identifying with a minor fraction of their ancestry or even making it up entirely.

The decline in competency:

Think of the American system as a series of concentric rings with the government at the center. Directly surrounding that are the organizations that receive government funds, then the nonprofits that influence and are subject to policy, and finally business at the periphery. Since the era of the Manhattan Project and the Space Race, the state capacity of the federal government has been declining almost monotonically.

While this has occurred for a multitude of reasons, the steel girders supporting the competency of the federal government were the first to be exposed to the saltwater of the Civil Rights Act and related executive orders. Government agencies, which are in charge of overseeing all the other systems, have seen the quality of their human capital decline tremendously since the 1960s. While the damage to an agency like the Department of Agriculture may have long-term deadly consequences, the most immediate danger is at safety-critical agencies like the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

The Air Traffic Control (ATC) system used in the U.S. relies on an intricate dance of visual or radar observation, transponders, and radio communication, all with the incredible challenge of keeping thousands of simultaneously moving planes from ever crashing into each other. Since air controlling is one of the only jobs that pays more than $100,000 per year and does not require a college diploma, it has been a popular career choice for individuals without a degree who nonetheless have an exceptionally good memory, attention span, visuospatial awareness, and logical skills. The Air Traffic Selection and Training (AT-SAT) Exam, a standardized test of those critical skills, was historically the primary barrier to entry for air controllers. As a consequence of the AT-SAT, as well as a preference for veterans with former air controller experience, 83 percent of air controllers in the U.S. were white men as of 2014.

That year, the FAA added a Biographical Questionnaire (BQ) to the screening process to tilt the applicant pool toward diverse candidates. Facing pushback in the courts from well-qualified candidates who were screened out, the FAA quietly backed away from the BQ and adopted a new exam, the Air Traffic Skills Assessment (ATSA). While the ATSA includes some questions similar to those of the BQ, it restored the test’s focus on core air traffic skills. The importance of highly-skilled air controllers was made clear in the most deadly air disaster in history, the 1977 Tenerife incident. Two planes, one taking off and one taxiing, collided on the runway due to confusion between the captain of KLM 4805 and the Tenerife ATC. The crash, which killed 583 people, resulted in sweeping changes in aviation safety culture.

Recently, the tremendous U.S. record for air safety established since the 1970s has been fraying at the edges. The first three months of 2023 saw nine near-miss incidents at U.S. airports, one with two planes coming within 100 feet of colliding. This terrifying uptick from years prior resulted in the FAA and NTSB convening safety summits in March and May, respectively. Whether they dared to discuss root causes seems unlikely.

Click below to read the rest of this excellent, excellent article:

The First World War took a significant bite out of the British Treasury, so much so that its main creditor, the rising United States of America, had to enter the war to ensure that it got paid back what it lent to the then-world’s greatest power. The Second World War managed to do to Britain what the previous one began: bankrupt it and end its once-glorious empire.

With half of the world’s manufacturing output located at home by the time of the end of World War 2, the Americans were not only the “arsenal of democracy”, but also the world’s factory. They had easily surpassed the British in wealth and strength, both military and financial. The sun had finally set on the UK’s empire, and they had to re-calibrate their role in a world that once largely belonged to them. What path did they choose? “Atlanticism” and the “Special Relationship” is what it is called, but in actuality it is a subordinate role to the USA.

A lingering hatred of the UK persists globally, much of it based on historical grievances (valid or not), but also because the UK does act as the yapping poodle sitting in the lap of the lumbering and clumsy (and getting clumsier) USA. No country has shown more deference to American foreign policy objectives than the Brits (see: Iraq wars, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, and now Israel vs. Hamas), and no country tries to portray itself punching well above its weight as they constantly try to do. Just look at the inflammatory rhetoric that has come out of Blighty to target Russia on a routine basis ever since Putin tamed the oligarchs. America is to be respected and feared, the yapping Brits are an irritant that few respect, yet require toleration due to their obsequious behaviour towards Washington that serves to protect them from harm.

British policy planners have routinely joined US adventures abroad in order to “stay in the game” and show fealty to their masters and extract what perceived advantages that they could possible receive from such a lopsided relationship. But is this “Special Relationship” really to Britain’s benefit? Aris Roussinos questions the benefits and concludes that Britain requires decolonization:

Such fealty to an imperial protector may be the lot of all small states: yet where British exceptionalism truly distinguishes itself is in the eagerness of our elites to serve their master, a yearning for subordination which at times arouses as much contempt as satisfaction in the imperial capital. Britain’s elites have chosen to view themselves as, if not equal partners in the imperial project, then a uniquely favoured ally, elevated in affection above rivals by the Special Relationship. That the Special Relationship is an entirely parasocial one is a truth American securocrats are generally too polite to mention, and too hard for their British equivalents to bear. The results have generally been disastrous: so zealous have our leaders been to prove their mettle in imperial wars, Britain committed itself to tasks in Afghanistan and Iraq that proved far beyond its abilities. This eagerness to go above and beyond Washington’s requirements may now be repeating itself both in Ukraine, where America’s second thoughts about continuing a war rapidly turning sour threaten to leave ultra-hawkish Britain looking dangerously exposed, and in the Pacific, where the Royal Navy has almost entirely refashioned itself for a vulnerable auxiliary role in the looming war with China.

Aris goes on to say that this Atlanticist position is viewed as “foundational” in the UK foreign policy community, and that adherence to it is the price of admission for those wanting to become part of it in the think tank world.

Given the heavy costs and dubious benefits of such a relationship, why should the notionally independent British state not look towards British interests first and foremost? Why should our defence establishment so jealously guard their position as Washington’s loyalest compradors while denying the true nature of their role? Stevenson’s book provides a rare, clear-eyed dissection of Britain’s humbled status. Largely a reworked collection of LRB essays on 21st-century warfare, featuring original reporting from the disastrous fallout of the Arab Spring — and I can personally attest there is no more radicalising argument against the American empire than direct observation of how the sausage is made — the book is at its strongest in its opening and closing chapters on the mechanics of British self-subordination, and its searing essay on Britain’s defence intelligentsia.

Stevenson dissects the strange case of the British securocrat class, the products of our cloistered strategic think tanks RUSI, the IISS and Chatham House, and their feeder school, Kings’ Department of War Studies. As he observes: “Among the British defence intelligentsia, Atlanticism is a foundational assumption. A former director of policy planning at the US State Department and a former director at the US National Security Council are on the staff of the IISS. RUSI’s director-general, Karin von Hippel, was once chief of staff to the four-star American general John Allen. In 2021, RUSI’s second largest donor was the US State Department.” Yet despite their obsequiousness to American interests, British security think tanks have “next to no influence across the Atlantic”. In so far as their strategic counsel has been followed by British governments, the results have been, at best, humiliating and at worst war crimes, dragging Britain into reckless campaigns “of the sort that nations were once disarmed for committing”.

Like the Five Eyes intelligence arrangement, the function of such institutionalised subordination is simply to align the British defence establishment with Washington’s fickle desires of the moment. Yet if the aim is to serve American interests, the results have proved of doubtful benefit to the imperial centre. For despite “the consistency of British servility”, the results for Washington are generally underwhelming. “Even British participation in the Iraq war was often a liability,” Stevenson observes, as in Basra where, after crowing about the Army’s superior abilities in counterinsurgency drawn from experience in Malaya and Northern Ireland, British “soldiers withdrew from the city in a single night like criminals leaving a burgled house”, leaving US troops to reimpose some fragile order. If Britain hoped to win some special favour from the Iraq adventure, American gratitude was not forthcoming. France and Germany were not punished for their refusal to join in, while Britain earned the dubious status of a regrettable partner in a dalliance Washington wished to forget.

As Stevenson remarks, “passionate Atlanticism proceeds on the assumption that the interests of American power are necessarily coterminous with those of Britain”, an unexamined belief that, if applied in reverse, America’s defence establishment would laugh at in amused horror. Even America’s one true foreign infatuation, with Israel, is now looking shakier than ever before: and there too, when the great ship of US foreign policy eventually changes course, our political establishment will follow in the slipstream, presenting their abrupt about-turn as a decision made in London. Yet the prospect of freeing ourselves from such an unequal relationship, unsatisfactory to both parties but surviving through sheer institutional inertia, is unlikely to come from Whitehall.

Britain “projects decadence” and not “power”:

Fortunately for the rest of the world, “Britain isn’t projecting power so much as decadence.” Through the strange alchemy of the MOD’s procurement system, British defence spending is not transmuted into effective military force. Indeed, “the main countervailing force to British militarism has been British economic malaise”, and as an arm of the British state, the MOD is not immune to its vices. Britain’s plummeting GDP is seen, by Stevenson, as a potential safeguard against disastrous foreign adventures. It must be said, however, that lack of capability has never yet prevented our leaders from hurling themselves into conflicts they cannot win, and there is no sign of this dynamic changing.

Aris argues that change in foreign policy won’t come from Whitehall, but from the USA, a country whose own foreign policy is both very fickle and highly hostage to internal domestic political considerations:

But ultimately, given the leaders we have and the worldview they have not yet shaken off, Britain has hitched its security to America’s wagon, and change, when it comes, will come from the imperial metropole. A Trump victory next year is more likely than not, and a question mark looms over Nato’s very existence. Here the trends toward strategic defeat followed by inward retrenchment look clearer every day. In Ukraine, the growing likelihood of an eventual Russian victory will present a great strategic shock to Europe, highlighting that American defence guarantees are severely circumscribed by the volatility of the empire’s domestic politics. The looming competition with China over mastery of the Pacific presents the greatest challenge military America has ever faced: Washington’s prospects of success look doubtful. From Africa to the Middle East, the flirtation of America’s client states with its strategic rivals has blossomed into committed relationships.

The sun is setting on the American empire as it once did on our own, and history will force on our defence establishment a reckoning with reality that they have long avoided. Perhaps Europe will be left to fend for itself in a newly-dangerous world, or perhaps we will be drawn tighter into the embrace of America’s smaller and more clearly-defined core empire. Whatever history has in store for us, the nature of Britain’s strategic relationship with its imperial patron means that these decisions will not be made in London. Empires make the rules, and their clients accept them, however vanity forces them to mask the hard realities of power. The weak, as ever, will do what they must.

Britain has been cast adrift, with #Brexit only emphasizing this condition. Currently experiencing a national malaise, a paralyzed political system, economic decline, etc., the Brits retain hopes of global importance while pursuing a foreign policy of slavish devotion to the son that surpassed him long ago.

It ain’t just the Brits either.

Some of you have read my essays lamenting the current crop of leaders of the EU and its member states and how they too have decided that being branch managers of USA Inc. is much better than being actual presidents and prime ministers. Gladly and embarrassingly accepting the financial costs of the USA’s proxy war against Russia, these failures and embarrassments have not only tanked European economic competitiveness, but have reduced the continent’s role to that of a collection of satrapies.

Lepold Aschenbrenner calls this period in irrelevance “Europe’s Political Stupor”, and urges renewed debate to “reinvigorate and reinvent liberalism”:

As the ideals of classical liberalism are once-again being challenged, we need new ideas and a diversity of approaches to reinvigorate and reinvent liberalism. It might be time to reassert the political in Europe and wake the Continent from its stupor.

It is hard to overstate the European fixation on America—and American politics in particular. I can report most accurately from Germany, since I grew up there; but from what I hear, the situation is similar across the Continent.

The recent American election provides just one case study. The presidential race absolutely dominated the news and public debate in Europe. German media probably spent more time covering the American election than a domestic general election. For weeks, German politicians were reduced to mere political pundits, blaring their shallow analysis of American politics in never-ending TV coverage.

And it wasn’t just 2020. When Barack Obama came to Berlin in 2008 as the freshly minted Democratic nominee, he drew a crowd of over 200,000. No German politician could hope to draw a crowd of even 10,000.

To be sure, because of America’s global power, an American presidential election can be highly consequential for European affairs. But the fixation with American politics extends to domestic political controversies without direct foreign policy consequences. The nomination and confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett, for example, was covered endlessly. At this point, I am pretty sure that a far greater proportion of Germans would know who Amy Coney Barrett is than could identify even a single judge on the German Constitutional Court.

Or take this summer’s Black Lives Matter movement. The protests in the U.S. quickly swept over to Europe, with scores of (mostly white) German youth taking the streets. But these protests weren’t about trying to confront German problems; they weren’t about the distinct challenges of rampant racial discrimination in Germany. Rather, they were mostly about showing support for an American political cause.

The metropole informs the provinces, and when combined with the behemoth that is American soft power, Americanization of the continent continues to pick up pace.

He points to dissatisfaction with technocracy as one reason for Europe’s obsession with the USA:

On the surface, German conventional wisdom decries the political divisions in the U.S.; it trumpets the supposed moral superiority of the German way over the American health care system or American foreign policy; it holds German democracy to be infinitely superior to American democracy (which, if you believe German media coverage, is on the verge of collapse and paralleled only by the Weimar Republic in 1933). But what this arrogance masks—and perhaps is deliberately intended to obscure—is the underlying reality of European “politics”: namely, that it is bereft of politics.

For the German voter has basically no say over his country’s fate. Sure, he may cast a vote in an election for parliament. But in the end, the same centrist parties seem to hold a majority in parliament, the same centrist parties form a coalition government, and the same party leaders remain in charge, making policy mostly through backroom deals rubber-stamped by the parliament. Besides relatively minor policy tweaks, the elections don’t seem to matter much.

And for all the German media’s handwringing about a “peaceful transfer of power” in the U.S., most Germans under, say, 30, have never witnessed a transfer of power in Germany! It’s always been Merkel. And really, the guy before her—even though he was from the opposing political camp—wasn’t all that distinguishable.

I have to take issue with this claim, but his description of politics in Germany doesn’t really differ from that in the USA. Take the claim of “rubber stamping by Parliament” and “backroom deals”, and apply that to the US Budget fight every year. The idea that Americans feel that their votes matter is hilarious to anyone who knows how the overwhelming majority of Americans feel about Congress.

The “cultural hegemony of the American left”:

We have noted how American politics dominates the European media and public square. Of course, America’s cultural hegemony goes far beyond that: Europeans watch American movies and TV shows, listen to American music, spend their days using American tech companies’ products, take advice from American scholars, and read American authors. Even trick-or-treating on Halloween, once a distinctly American practice, has conquered the Continent.

At this point, it behooves us to get a bit more precise about America’s cultural hegemony. For the hegemony is not one of America generally, but one of the American Left.

The Left has achieved a suffocating cultural dominance in elite America. Newspapers, television stations, Hollywood, universities, tech companies—they have all become a one-party state, so to speak. The main political controversy within these institutions seems to be between the mainstream left and the radical left.

Europeans aping attitudes that they see from across the pond:

But those are exactly the institutions to which Europeans look. One of the main newspapers read by the Berlin political class, for example, essentially plagiarizes a substantial fraction of their articles from the New York Times. So whatever the New York Times writes, whatever political viewpoint underlies their reporting, becomes the operating premise of the German political class. European youth idolize American stars. So when those stars “courageously speak out” on a political issue (i.e. endorse the Left party line), European youth take the cue. The preeminent public intellectuals Europeans follow on Twitter are mostly American. So as wokeism ascends in American academy, it seeps into the European mind as well. The Left’s cultural hegemony in elite America thus becomes cultural hegemony in Europe as well.

This cross-Atlantic monoculture is a deeply unhealthy state of affairs. At the core of Western classical liberalism is a commitment to a diversity of ideas that compete in the political marketplace. Only such a robust and wide-open debate can ensure dynamic and lively political understanding. As much as this diversity of ideas is essential within a country, it is perhaps even more essential across countries. As liberalism itself is once again being challenged by rising authoritarianism, we need different nations with different approaches to reinvigorate and reinvent liberalism. But in a monoculture, without new ideas, competitive pressures, or the benefits of trial-and-error, liberalism will wither.

Does this differentiation extend to Fidesz and Orban? What about AfD?

To be clear, at least in the German case, the banishment of the political was partly a deliberate choice. After the horrors of WWII, horrors that had emerged from the contentious politics of the Weimar Republic, the post-WWII West German state, the Bonner Republik, was meant to be as boring as possible. To this day, most German politicians resemble bureaucratic administrators more than visionary leaders. The “political,” at least in the way defined by Carl Schmitt as that existential distinction between friend and foe, was to be excised from Germany—for the political in German hands had caused too much harm.

Perhaps, then, the Western monoculture is the price we pay for peace. This is worth taking seriously. But the Germany of today is not the Germany of the early 20th century; the Europe of today is not the Europe of the early 20th century. The Continent has been reshaped along liberal lines. It is now a stalwart of the ideals of liberty and peaceful coexistence.

Okay, but now this:

The banishment of the political was intended to subdue the impulses of nationalism and demagoguery. But if the European mainstream continues to deny the citizenry a true democratic debate, that may well pave the way for an authoritarian strongman who promises the citizens renewed control of their nation’s destiny. We already see inklings of this in Poland, Hungary, France, the Brexit vote to “take back control,” and a resurgent far-right in Germany that is blasting open the previously narrow confines of political debate. The Continent is ripe for awakening. If liberalism does not lead this charge, illiberal authoritarianism will.

So the “debate” that the author wants to see is really just him wanting Classical Liberalism to return to the fore and not actual diversity of thought and opinion?

Shit essay, I apologize for sharing it.

I have quite A LOT to say about the genocide case brought forward by South Africa against Israel at The Hague, but I am going to save those thoughts for an essay in the near future. Those of us from the ex-YU have a lot of insight into this world with its arcane rules and heavy politicization.

In the meantime, here’s a tally of who is siding with Israel and who isn’t:

South Africa says more than 50 countries have expressed support for its case at the United Nations’ top court accusing Israel of genocide against Palestinians in the war in Gaza.

Others, including the United States, have strongly rejected South Africa’s allegation that Israel is violating the U.N. Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Many more have remained silent.

………

The majority of countries backing South Africa’s case are from the Arab world and Africa. In Europe, only the Muslim nation of Turkey has publicly stated its support.

Global South vs. Global West?

No Western country has declared support for South Africa’s allegations against Israel. The U.S., a close Israel ally, has rejected them as unfounded, the U.K. has called them unjustified, and Germany said it “explicitly rejects” them.

China and Russia have said little about one of the most momentous cases to come before an international court. The European Union also hasn’t commented.

I will also explain China’s and Russia’s hesitancy in my upcoming essay.

Germany’s historical baggage has led to take a strong public stand in favour of Israel:

Germany’s announcement of support for Israel on Friday, the day the hearings closed, has symbolic significance given its history of the Holocaust, when the Nazis killed 6 million Jews in Europe. Israel was created after World War II as a haven for Jews in the shadow of those atrocities.

“Israel has been defending itself,” German government spokesperson Steffen Hebestreit said. His statement also invoked the Holocaust, which in large part spurred the creation of the U.N. Genocide Convention in 1948.

“In view of Germany’s history ... the Federal Government sees itself as particularly committed to the Convention against Genocide,” he said. He called the allegations against Israel “completely unfounded.”

Germany said it intends to intervene in the case on Israel’s behalf.

The Islamic world has naturally come out against Israel:

The Organization of Islamic Cooperation was one of the first blocs to publicly back the case when South Africa filed it late last month. It said there was “mass genocide being perpetrated by the Israeli defense forces” and accused Israel of “indiscriminate targeting” of Gaza’s civilian population.

The OIC is a bloc of 57 countries that includes Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Egypt. Its headquarters are in Saudi Arabia. The Cairo-based Arab League, whose 22 member countries are almost all part of the OIC, also backed South Africa’s case.

South Africa drew some support from outside the Arab world. Namibia and Pakistan agreed with the case at a U.N. General Assembly session this week. Malaysia also expressed support.

“No peace-loving human being can ignore the carnage waged against Palestinians in Gaza,” Namibian President Hage Geingob was quoted as saying in the southern African nation’s The Namibian newspaper.

Malaysia’s Foreign Ministry demanded “legal accountability for Israel’s atrocities in Gaza.”

India:

India’s foreign policy has historically supported the Palestinian cause, but Prime Minister Narendra Modi was one of the first global leaders to express solidarity with Israel and call the Hamas attack terrorism.

In the middle:

Brazil said it hoped the case would get Israel to “immediately cease all acts and measures that could constitute genocide.”

Other countries have stopped short of agreeing with South Africa. Ireland premier Leo Varadkar said the genocide case was “far from clear cut” but that he hoped the court would order a cease-fire in Gaza.

South Africa has had a history with Israel, with the ruling ANC pointing out how the Israelis had very close relations with the former Apartheid regime that ruled the country.

Revenge?

We end this weekend’s SCR with a very subjective (aren’t they all?) ranking of all the James Bond movies to date:

10. The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

This is the best of the Roger Moore James Bonds, and it’s all about submarines! A bunch of underwater nuclear warheads have gone missing, so Bond and this woman whose boyfriend he killed go on a sub-aqueous adventure to find them. Also, the villain has webbed hands. (Look, I said it was the best Roger Moore Bond movie, not the best BOND movie.)

I am a Roger Moore Supremacist and haven’t seen a single Bond film since he left that role. Some of my favourite memories are watching the campy and funny Bond movies that he starred in as I watched them with my father. Jaws was my favourite character!

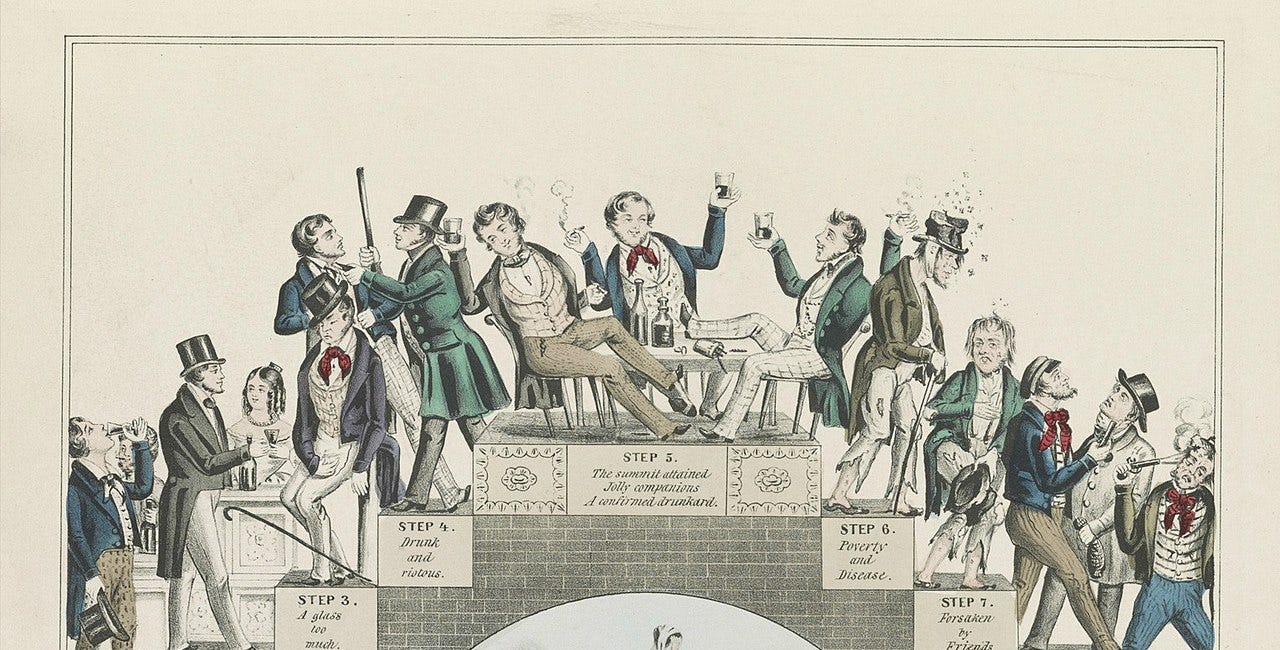

For those who missed it, we’ve started the latest entry in the FbF Book Club. In this iteration, we are looking at the history of Alcohol Prohibition in the USA, with a focus on the actual period itself that lasted from 1920 until 1933. The book is Daniel Okrent’s “Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition” (1920). A bestsellter, it’s written in a popular style.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Meritocracy of any kind is only established when elites face either the threat of revolution from below or invasion from without. The soporific social peace established by consumer capitalism and the relative calm of post-Cold War hegemony removed any urgency from the equation, enabling the excesses of DEI to mount. Now that social peace is breaking down at home and inter-state competition heating up America needs to reset the system.

Niccolo is dead right about the time frame. America has a little bit of time left to adjust though I am not sure that it has a full twenty years.

The weakness of a lot of thinking about the competency crisis is the assumption that the regime is even aiming for optimal results. It isn't. The regime is aiming for internal stability. Meritocracy is potentially very disruptive indeed.

If Turbo America makes a meritocratic turn, would this necessarily benefit anyone within the US?

The US might choose to simply recruit the best from the global pool, leaving the US with a wholly foreign professional and managerial class. Turbo America would end up like Egypt under the Mamelukes which had a governmental and military elite of Turkish, Balkans and Caucasian origin and a mostly Levantine commercial elite.