Saturday Commentary and Review #132

"America Has Lost the Plot", Disability Inflation, A "Far Right" EU?, British Liberals' American Turn, Rammstein as Emblematic of "Germany's Right Wing Shift"

Every weekend (almost) I share five articles/essays/reports with you. I select these over the course of the week because they are either insightful, informative, interesting, important, or a combination of the above.

We’re in the dog days of summer where everything slows down as people head to the cottage or to the beach to get away from work and real life. This is (at least to me) a good time to reflect and take stock, and especially to mentally prepare for what lies ahead.

What lies ahead of us is the kick off of the 2024 US Presidential Election campaign, one in which a lot is at stake not just for Americans, but for us non-Americans too. There is only one important battle: Trump vs. the US Elites, represented by Joe Biden. All other candidates are supporting cast members.

At present, the US Deep State is trying to disqualify Trump from 2024 by all legal means available to them. Despite this (and in spite of this) his polling numbers remain stubbornly high, serving as a a barometer for the current US political climate. With this is mind, now is an excellent time to take a deep breath and exhale, taking stock of that climate as a hole. To help us do this, I am sharing with you a great interview with novelist and journalist Walter Kirn, one in which he addresses the madness that is consuming the USA these days.

On how everything he was taught as a boy is now “wrong”:

The Cold War lesson was more sophisticated and went on even longer into junior high and high school. It centered on books like Nineteen Eighty-Four, Animal Farm, Fahrenheit 451, and other depictions of the dangers of a totalitarian world. We were asked to congratulate ourselves as young Americans on our freedom and clarity and basic goodness compared to this lurking threat from the Soviet Union, in which the citizens were all forced to think alike, act alike, and be alike.

Over the years, it has caused me great consternation that the heavy aversion to totalitarian, dictatorial, and top-down systems that was implanted in me is now kind of useless—and even dangerous. As I discern trends in our society that seem to resemble those I was warned against and raise my hand to say that I don’t like this, I’m told that, somehow, I’m out of step, I’m overly alarmed, and I’m maybe even on the wrong side.

But, I want to reply, this is only what a seventh-grade Minnesota public school student was taught to fear, taught to be on the lookout for, and now you’re telling me it constitutes some kind of dissident position to be afraid of these things?

All the American values that Kirn was brought up with now leave him outside of the present acceptable bounds of discourse. This goes I imagine for almost all of my American readers as well.

Kirn goes on to say that there was an idyll that began from the collapse of the Soviet Union and that made it through the War on Terror (which he viewed as “manageable”), but that this was shattered by the 2016 US Presidential Election:

It was only around the mid-2010s, with the election of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, that I felt the clouds really begin to gather again.

When I went to cover the Republican Convention in Cleveland for Harper’s in 2016—this is not remembered very clearly now—we had the Ferguson riots, and we had a few really astonishing outbreaks of what seemed like racial violence. A bunch of Dallas police officers were shot not long before the convention. Reporters were actually warned, in a way that made the news, that they might want to wear bulletproof vests in Cleveland; it was imagined that it might very well turn into Chicago in 1968.

My earliest memories as a child were of the Vietnam War on TV and the student protests. Bridges in Minneapolis were blocked by protesters, bonfires were lit, and there were bombings all the time. If you turned on the TV until about 1976, you were getting a constant down-beat feed of internal dissent—and, of course, assassinations. I was old enough to be conscious by the time Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were shot.

Right around the time I went to Cleveland, I saw that my wife was concerned for my well-being and that there was reason for her concern in the rhetoric that was breaking out on the news. But when I got to Cleveland, nothing much happened. Alex Jones was driving around with a bullhorn and there was a lot of noise and circus-like convention rhetoric, but nothing bad happened. I thought, wow, this is all overblown.

But then…….

As the Trump presidency started, almost instantly—even back at the convention—the notion was that he was a kind of instrument of dictatorial Russia. I was thinking, are they going to keep this up into his presidency? I can see why, in the heat of a campaign, you might throw all kinds of overheated accusations at somebody.

………

When Trump won, I saw that rather than come together, as had been the norm after previous presidential elections, the suspicion of this figure ramped up. There were lists in the mainstream press of publications that were suspected to be Russian fronts; they included all sorts of outlets I happened to read, from CounterPunch on the left to the Drudge Report on the right. I thought, are we really going to push the narrative that the president is a Russian agent and a huge part of our media has been infiltrated and subverted by enemy agents? That America is headed for some terrible reckoning over race, international alliances, and so on?

Since the fall of 2016, it has gotten worse and worse. More American institutions have been cast as dubious, unpatriotic, and perhaps manipulated from abroad. More American attitudes, whether they be religious, cultural, or even intellectual, have been redlined as dangerous. More individuals from citizens to media figures to authors and artists have been cast in the role of dangerous dissenters.

The sum total, to bring it right up to the present, is that we now live in an age of profound anxiety. The political emergency, the environmental threat, and later COVID, were all globbed together as one giant example of our need for vast controlling authority that would keep us from dying. No longer could the citizens be trusted to make their own decisions, associate freely, speak openly, and spontaneously carry out their lives. All the risks had risen to the ultimate level, DEFCON 1. Our communications had to be monitored—and even manicured. Politics was too dangerous to be left in the hands of the population. Very suddenly, on every front, there seemed to be a rationale for total control and also a scenario in which, should we fail to yield to that control, doom was certain.

Where I differ from a lot of you readers is that what Kirn has described so eloquently above is to me symptomatic of the transformation of the USA, where instead many of you are of the opinion that it indicates that the USA is falling apart.

The upending of traditional relations in favour of digitized ones that flow through authority:

I like to imagine the world from the vantage point of an alien or someone who doesn’t speak the language and see what’s going on in structural terms. I think you hit on it. Instead of this lateral relationship with our community and our neighbors and our family, what’s being proposed is that everyone triangulate their relationships through an authority center. Whether the method of that triangulation involves having talking points for Thanksgiving dinner or just going on social media to find out what good people think and then repeating it, the trend seems to be toward the outsourcing of all responses, thoughts, and reactions.

Why do I hate that so much? Maybe that’s the solution to our ignorant and fallen status in society. Let’s take the devil’s advocate there. Over the last few years, we’ve been told that there are certain infallible organs of truth: the intelligence community, Science with a capital S, mainstream media, etc.

It was my privilege to meet a physicist named Murray Gell-Mann who discovered the subatomic particle known as the quark. But he also is the namesake for a principle of skeptical inquiry called the Gell-Mann Effect. When you read one article or piece in a newspaper on a subject you happen to know something about and you find it to be misinformed, wrong, or even deceptive, why do you then assume that the same paper is accurate about subjects that you don’t know about? Why would you extend credence to that source on other topics when you’ve caught it lying or being wrong about one you do know about?

The media no longer informs the reader and can no longer be trusted:

Well, that’s the real question. I’m going to stipulate—no one has to agree with me on this, but I have tried the case and come to this conclusion for myself—that between the deceptiveness, the agenda-driven nature, and the social-media-oriented vapidity of the press, it is no longer a reliable source of information about the world. It’s a very good source of information about itself. If you wish to know who’s up and who’s down, who’s in and who’s out, who scored points and lost points, it’s a great scorecard. But if you’re looking to find out what’s going on, it’s a terrible one. In fact, it will actually conceal what’s going on in almost every respect. So I’ve given up on it.

The press is a document, it’s a stage play, it’s an artifact, and insofar as I want to use its own methods and study it as such, it’s kind of fascinating. But as a guide to what’s happening? It’s worse than useless. It’s beyond propaganda. Propaganda was a kind of simple word that described boosting a point of view in a pretty obvious way.

The impossibility of learning the truth via the media:

Garbage in, garbage out. This idea is that you can somehow split the difference between various sides. But anyone who is at all a systematic thinker realizes the sides were conceived in opposition to each other. So if the first one was wrong, the second one is just the opposite of it, but it’s as wrong in the opposite way. And maybe a third one came along that was some kind of combination of the two, but it was just the combination of two things that were wrong. And now I’m going to put them together, divide by three, and come up with the real answer?

You don’t get any closer to the truth by performing that operation. All that operation reveals is who the powers that be are, what they think is going to work, and what’s succeeding now in terms of getting attention versus what was succeeding yesterday. You are fooling yourself if you think you can decrypt this misinformation layer—whatever you might call it—and get to reality. This game of running a counterintelligence operation on our information streams appeals to the ego, and to our sense of intrigue and our own skill, but there’s no reason to believe it gets us any closer to the truth and it may indeed take us further away. On issue after issue, we seem to be involved in prefabricated dialectics, oppositions, and architectures. Maybe the issue du jour isn’t even an issue at all.

A simulacra! Maybe Kirn is right and maybe my attempt to decode media is a struggle that I can never win?

On the media news cycle and how it works to destroy memory:

But once you start preaching the virtues of forgetting, everything gets forgotten. The reason people want to forget is that they don’t want to be slowed down. Everything that you remember is in a sense stuck to a world that has now been superseded. Forget the particular moral lessons. To remember at all is to be inefficient in your encounter with the present.

One of my formative intellectual influences is a guy who some consider a crackpot, a psychologist named Julian Jaynes who taught at Princeton while I was there. He was an outlier in the academic community and he published one book called The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.

His thesis was that before about 3,000 years ago, consciousness was an entirely different thing. People didn’t “think” consciously, they experienced life as getting commands from a seemingly outside god-like agency. Instead of the modern form of consciousness, “I think I should go to the store,” causing me to get up and go to the store, ancient people heard a command: “Go to the store.” And it was often in the voice of an ancestor, a leader, or a god. Jaynes claimed the primordial form of consciousness was a lot like what we now call schizophrenia; it was hearing voices, hearing commands, and acting immediately on them: “Go out and start planting!” I think we may be returning to that state, where consciousness is no longer an interior process, one that we carry around with us, one that is locked in the suitcase of the mind.

If you want to throw off the ballast of the past in order to be more responsive to the present, there’s a logical next step which is to be no longer loyal to the present—to exist in a constant state of anticipation—such that one does not even form memories to get attached to! You don’t bond with the present because you’ve learned that it’s about to become the past, and the past is a bad thing, and memories only hold you back, so why even form them? Why even have experiences? Because if I have an experience that lodges deeply enough in me, it will turn into a memory and it will hold me back.

Kirn, now 60, is from Minnesota and has lived in Montana these past 30 years. He has the sharp eye necessary for a novelist to succeed, and has also had a career in literary criticism, meaning that he has worked with some centres of power and has thus been exposed to how they operate.

He freely admits that he has been left behind by the rapid shifts in US politics and culture, like many of you have as well. The old, cherished assumptions and shared values are not just anachronistic, but are now deemed “regressive” and even “fascistic”.

Kirn, like all of you, quickly picked up that this isn’t your father’s America, and all the old rules no longer apply. We’ll see how that pans out in 2024.

If you incentivize a behaviour, you are almost always certain to get more of it. If that incentivization is formalized through procedural means, you will certainly get people gaming that system to their own advantage. And why not? We live in a post-shame society after all.

The coddling of North American youth is part of this post-shame environment. Universities were once about the free exchange of inquiry and knowledge, but now often resemble little more than young adult day care facilities. The feelings of students (who pay an incredible amount of money to attend these schools) will take precedence over the education that they are purportedly there to receive in the first place. This campus coddling does not prepare them for the real world; in fact it does quite the opposite in sheltering them from the impact of their own decision-making.

I came across a very interesting essay this past week on the explosive growth of US college students claiming disabilities, and how schools have to cater to them by law. What I learned was new to me, but it did not surprise me one bit.

Over the past five years, however, my academic colleagues and I anecdotally noticed a significant increase in the frequency and type of accommodations being requested by accessibility offices. Unlike Jason’s need for a notetaker due to the physical limitations from cerebral palsy, the majority of these recent requests are almost exclusively for a burgeoning number of college students classified as having mental health issues (particularly anxiety or depression) and learning disorders or attention-deficit disorders, even when those conditions do not significantly impact a student’s life activities.

The days of receiving one letter from the accessibility office every once in a while are over. It is now routine to have multiple students in each class providing a letter requesting accommodations. These include needing up to twice the amount of time allotted to take an exam; requesting permission to miss a class due to anxiety or a therapy appointment (“flexible attendance”) or to take an oral exam in private or by another means of assessment due to anxiety; and requests to negotiate flexible submission dates for assignments that are not available to others in the class.

Naturally, the doors to this were swung open wide from above:

Upon further research I have found that the increase in the number and scope of accommodations is not anecdotal, nor a kind of confirmation bias. It instead reflects recent changes to the ADA Amendments Act that expand the definition of what is a disability to the point of being meaningless—changes that have opened the door to accommodations that fundamentally change course structure, content and assessments. This increase also reflects an evolving sensibility that removing obstacles and making things much easier for students is the best way to ensure equity rather than equipping the next generation with strategies and tools they need to meet challenges in a workforce—and in life—that will often not accommodate.

The numbers:

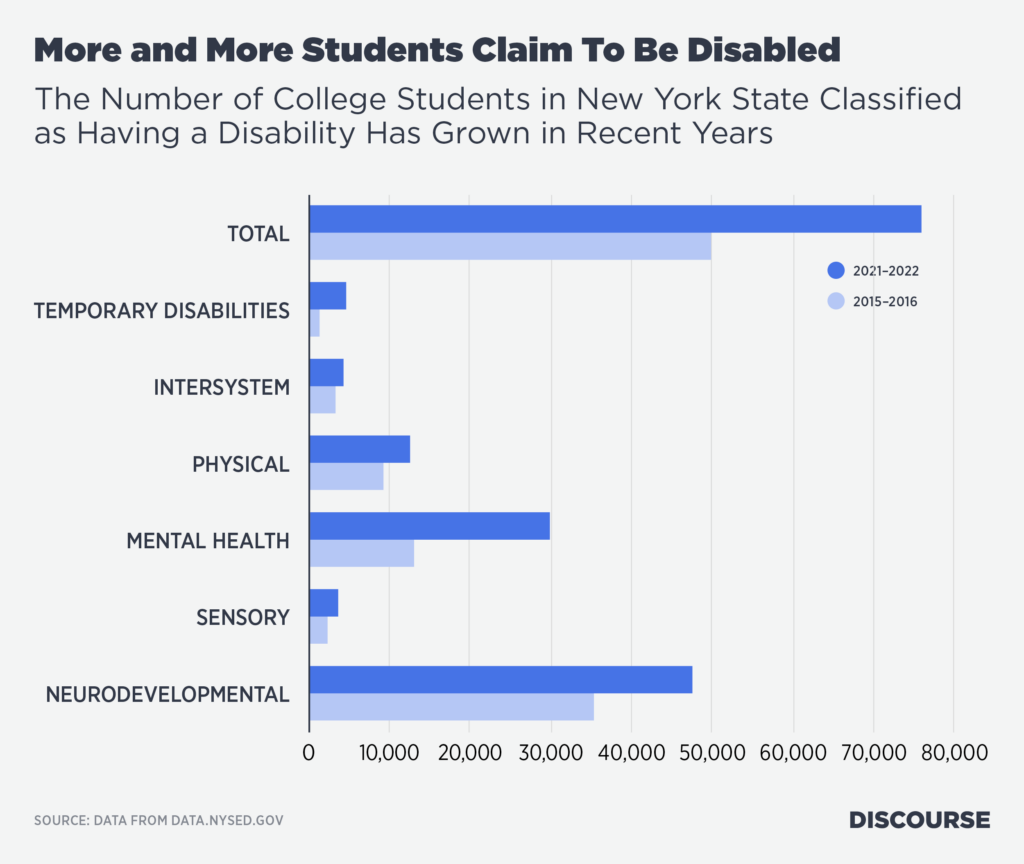

In 2016 a remarkable one-fifth of the undergraduate population in the United States was determined by their college to have a disability, with learning disabilities, attention-deficit disorder and the psychological issues of anxiety and depression comprising the vast majority of these disabilities. This is an enormous shift from the pre-2010 era, with classifications and accommodations doubling in just 12 years. New York State Department of Education data sets provide a dramatic snapshot of this nationwide trend. Even as higher education enrollment has contracted, the number of those classified as having a disability has grown spectacularly, with a 53% increase between 2015 and 2022 among those seeking degrees or credit-bearing certificates. There was a 130% jump in those with mental health disability classifications and a 33% increase in neurodevelopmental disability classifications (more than 50% of which were ADHD, followed by learning disabilities).

Expansion:

The new premise is that such problems don’t need to be chronic, nor do they need to severely restrict a student’s life in any meaningful way. Furthermore, the focus has shifted away from formal diagnoses, so there’s no longer any need to provide extensive evidence through medical or independent professional documentation. Disability office staff can rely on a mixture of student self-reporting and the staff’s own observations and professional judgment in determining whether a student has a disability meriting an accommodation and what that accommodation might be. At the same time, the prominent organization of disability service professionals, the Association on Higher Education and Disability, issued a guidance saying these changes were necessary to promote social justice in higher education.

A shift away from formal diagnoses spurred on by changes that were “necessary” to promote social justice in higher education.

Naturally, the rich are gaming the system:

Contrary to the best social justice intentions of Association on Higher Education and Disability and disability office staff of each university, broadening disability classifications and making their associated accommodations easier to acquire has mostly benefitted individuals who are anything but marginalized. Although research shows a relationship between learning disability classifications and socioeconomic status (e.g., those with the lowest income and the highest income were more likely to be classified as disabled than middle-income students), the students most likely to get an accommodation are those from high-income families and those who attend the priciest, most selective colleges. Consequently, 27% of Amherst, 26% of Brown and 22% of Barnard students get accommodations. In fact, there was a 292% increase in students classified with disabilities at the top eight liberal arts colleges over the past 12 years, which led to their having a student population with a 4.25 times greater percentage of students with accommodations than in community colleges, which serve a disproportionate number of low-income students and students of color.

The impact:

Many of the students who are accommodated are actually being badly shortchanged. Long-term equality means that college students of all backgrounds, including those marginalized by race or income, should graduate with the ability to take an exam in the format intended, read at a pace that would be expected in a professional career and make an oral presentation … in front of a group of people. If, at the college level, students are unable to meet universal curricular and testing standards with the support systems of tutoring and therapy in place, the college should not change the bar to ensure that they do. No driving school would allow students to do their driver’s exam on a closed road, with a bumper car or grant them time and a half to decide whether or not to merge onto a highway, even if the student had anxiety or a learning disability. The rubber needs to meet the road in college.

It is time to push back against the pervasive creep of disabling college disability classifications and accommodations. Otherwise, we will continue to degrade the rigor of the college curriculum and standards and, ultimately, the significance of a college degree.

“Degradation” is the key word here.

It was my contention prior to #Brexit that an EU minus the UK would shift to the political right. So far my prediction has proven accurate, even if the machinery of the EU itself is still in the hands of liberal Eurocrats.

The majority of this shift can be chalked up to one factor: migration. Europeans by and large do not favour the mass migration of non-Europeans into Europe. This is why they are never asked directly about it. Angela Merkel’s folly of inviting over one million migrants into Germany is what led to the victory of #Brexit, and to the rise in popularity of right wing parties across the continent. It was simple cause and effect.

The smart centre right parties went on to co-opt the anti-migration stances and policies of these right wing upstarts (and in the case of Denmark, the Social Democrats were the ones to do the co-opting). This served to take out the air inflating the support of the right and far right parties challenging them. Nevertheless, these parties are now firmly entrenched in the parliamentary systems of almost all European countries.

Euroliberals have accepted this reality, and are now worried that this latest surge in support for right/far right wing parties threatens to engulf their entire European project:

There are now a number of radical-right governments in EU member states – not just in Central and Eastern European countries like Poland, which, against the background of the war in Ukraine, is widely seen as more influential in the EU than ever before, but also in founding member states like Italy, where Giorgia Meloni became prime minister last October. Even in Germany, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is now level with the Social Democrats in the polls.

One of the reasons it has been so difficult for many people to even imagine a far-right EU has to do with the way we think about the EU itself and the far right’s relationship with it.

We tend to idealise the EU as an inherently progressive or even cosmopolitan project — making it seemingly incompatible with far-right thinking. In my forthcoming book Eurowhiteness, I argue that the ‘pro-European’ tendency to think of the EU as an expression of cosmopolitanism has created a kind of blind spot around the possibility of what might be called ethnoregionalism – that is, an ethnic/cultural version of European identity analogous to ethnonationalism, which is closely connected to the idea of whiteness. In other words, a far-right EU is – at least theoretically – possible.

Not all hard right Europeans are opposed in theory to the EU project:

At the same time as idealising the EU, we also simplify the attitude of far-right movements towards it – as if they were straightforwardly nationalists who opposed the idea of Europe. In reality, there is a tension within far-right thinking between nationalism and civilisationism. The far right in Europe does not simply speak on behalf of the nation against Europe, but also on behalf of Europe – that is, on behalf of ‘a different kind of imagined community, located at a different level of cultural and political space’ than the nation, as the sociologist Rogers Brubaker has put it. In particular, its rhetoric focuses on the idea of a threatened ‘European civilisation’.

Cooperation on the right at the continental level is possible and is happening:

Another, more practical reason why many could never imagine a far-right EU was the assumption that far-right parties could never cooperate across borders. It was thought that, unlike centrist ‘pro-Europeans’ who believe in cooperation, far-right parties would end up fighting with each other – and in so far as a far-right EU was possible, it would be one that would return power to member states. Contrary to this belief, however, far-right parties seem to be cooperating with each other quite effectively – and some may even be willing to accept further integration, for example on migration policy, provided it is on their terms.

The centre-right has “moved to the right” (what I said earlier about co-opting):

Meanwhile the centre right has moved to the right on cultural issues. The lesson it drew from the rise of populism is that, while opposing the far right – and to defeat it – it needed to take on elements of its agenda. Together, these two trends have produced the basis for a compromise between the centre right and the far right: the centre right would move further to the right on identity, immigration and Islam, and the far right would become less Eurosceptic. (In this respect the AfD is outlier.)

The threat to Euroliberals is growing:

Traditionally, a de facto grand coalition ran the EU against the opposition of the Eurosceptic far right and the far left. But that is now changing. In 2019, Ursula von der Leyen was elected as European Commission president with the help of votes from Fidesz, which remained in the EPP despite its transformation into a radical-right party. And after next year’s European Parliament elections, an alliance between the centre right and the far right could produce the most right-wing European Commission yet.

The compromise between the centre right and the far right is producing a kind of ‘pro-European’ version of far-right ideas and tropes, centred on the idea of a threatened European civilisation – what I have called the civilisational turn in the European project. How far this far-right takeover of the EU will go will depend on whether ‘pro-Europeans’ who reject civilisational thinking are willing to oppose it or simply go with the flow to maintain European unity.

European rightists have come to learn that ceding the ground to Eurocrats provides zero benefit and more and more drawbacks. Only by seizing and re-purposing that machinery can proper reform take place.

I’ve written about the Americanization of UK politics on this Substack in the past, but I feel the need to bring it up once again thanks to this opinion piece from the Financial Times, a UK publication. The author agrees with me that post-#Brexit Britain is now moving even faster towards an Americanization of its political culture, as it distances itself from Europe at the same time:

How did that polite detachment from America turn into what is now total, cringing, round-the-clock absorption in its public life? Leave aside the “woke” thing. Even middle-of-the-road liberals in Britain live in a world of Daily Show clips and piled-up copies of the New Yorker. This wasn’t happening a generation ago. And the photo negative of it is a serene incuriousness about the mental life of their own continent. When did something European last penetrate the British cognoscenti? Prime-era Michel Houellebecq? Or the Scandinavian TV dramas? This is a Brexit of the mind.

To the author, this trend is illogical:

This Americanisation would be easier to understand if the US were an ever mightier force in the world. But it has a smaller share of global output than it did in 2001, when I heard Schröder speak. The dollar accounts for a lower share of currency reserves. America’s military now has a rival worth losing sleep over. There is less cause, not more, to face west. Yet America’s psychic hold on the British bien pensant has tightened over the period.

Americanization is embraced by both the political right and left:

Last week, breaking my policy against west London, I attended the launch of Tomiwa Owolade’s This Is Not America in Holland Park. Its argument — that US race relations don’t map on to Britain’s — has needed saying for years. The prose has the tranquillity that doesn’t tend to come, if at all, until middle age. (The author is in his twenties.) And so the book deserves to succeed in its central mission.

It has no chance, of course. Something has changed in liberal Britain, and it predates Brexit. All my life, it was the right that was immersed in Americana. The left has joined them. There is nothing in this for the US. First, being obsessed with America is not the same as being pro-American. British liberals still disagree with the US line on Israel and much else. They just do so with a rising vocal tone at the end of each sentence.

Is soft power the last thing to go?

Perhaps a great power’s cultural influence, like an ageing gigolo’s charm, is the last thing to go. Long after Britain lost its might, there were people in Hong Kong and Zimbabwe moaning about their servants and describing things as “just not cricket” in a way no one in England had done since 1913. Plus anglais que les anglais, was the phrase for these tragicomic people and their affectations. How things come round. Don’t be more American than the Americans.

Don’t worry, Bongs. This Americanization is happening on the continent as well.

We end this weekend’s Substack with a very ridiculous essay on how the continued popularity of German musical act Rammstein “symbolizes” the “hard right turn” in Germany.

But Rammstein’s offensiveness extends beyond its aggressive misogyny to something that—surprisingly, given Germans’ sensitivity to such matters—has garnered even less scrutiny. The band’s toxic masculinity is part of a right-wing chauvinism that finds ample political expression today in Germany in far-right populism—and it is currently on the rise. Rammstein’s schtick—all supposedly a spoof—is a take on/spins off of Teutonic misdeeds, insidious evil, and despotism. Germany’s most successful contemporary cultural export is an act that flaunts Germanic symbolism, jack-booted goose-stepping, and Leni Riefenstahl aesthetics—to the adulation of sold-out stadiums worldwide. It is the best-selling German-language band in history, with more than 20 million in album sales. Although this Deutschtümelei (excessive display of Germanness) flies in the face of a liberal, modern Germany, the band has largely been given a free ride on it.

German nationalism today isn’t that of Rammstein’s performances, but Rammstein speaks to right-wingers who deeply resent Germany’s cultural boundaries and pursue their own violent strategies for expanding them. Since Rammstein is ramming through these same postwar impediments—although it is, the band assures us, as ironic critique—it lands itself on the same side as the rightists at a precarious time: when the fortunes of far-right parties and number of hate crimes are spiking across the country. A far-right party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), sits in Germany’s legislature, the Bundestag, and currently polls at an all-time high of over 18 percent. Last year, the number of right-wing hate crimes also hit an all-time high. A new poll shows that a third of men under 35 years of age think it’s OK if men slap their female partners.

The group’s 2019 music video “Deutschland” (Germany), for example, entails a nine-minute, bombastic maelstrom of sinister, blood-splattered, extraordinarily creepy snippets straight from German history, from murderous encounters between Roman legionnaires and Germanic pagans, through the Holocaust, to Soviet communism. The entire horror show plays out over Rammstein’s musical fare: Lindemann’s rumbling, deep-as-a-mass-grave vocals, hypnotic synthesizers, and intermittent bursts of distorted, down-tuned guitar riffs. By far the most troubling scene was released first as a trailer: four band members dressed as Jewish concentration camp prisoners, standing at a Nazi gallows amid SS officers, nooses around their necks.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

Hit the like button at the top of the page to like this entry. Use the share or re-stack buttons to share this across social media. Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so.

Three new interviews in the works, plus a couple of essays. Bear with me!

re: disability and incentives, I remember seeing an article a while back that noticed how reports of things like chronic back pain vary from country to country in a way that tracks how generous disability payouts are. The more you incentivize disability, the more you'll get, just like with anything else.

On more than one occasion I've had students in college tell me about the generous accommodations they have due to their highly-questionable "ADHD" or whatever. When I ask whether the elephantine quantity of recreational drugs they're using might also be impairing their concentration, they react indignantly as if having the accommodation is their right. Not to vilify the students too much, they're responding to incentives and the world we've made for them after all.