Saturday Commentary and Review #124

UK Malaise and Decline, Fukuyama vs. Fukuyama, Ireland's Oppressive Hate Speech Legislation, NGOs Against Transparency, NYC Gangster Big Jack Zelig

One of the most important themes of the West these days is the political civil conflict between centre and periphery. Think about how much wealth, power, and cultural influence is held in places like London, Paris, New York City/Washington DC/Los Angeles, etc., and compare it to the rest of their respective countries. Each of these capitals of finance, culture, and politics dominate their countries so absolutely as to render the rest an effective terra incognita to outside observers.

While the USA has distributed centres of power throughout the country, both France and the UK are cases where the national capital is so utterly dominant, appearing to the casual observer that the rest of France exists only to serve Paris, just like the rest of the UK for London.

Even though France is highly centralized administratively, its capital is not as large a vortex as London is for the UK. Thatcher’s de-industrialization has rendered large swaths of the UK redundant, leading to severe economic decline coupled with social free fall. By putting all of its eggs in one basket (pumping up the City of London as a global financial centre), the UK capital sped up its already-existing centrifugal force, sucking up all value from the rest of the country and re-locating it on the banks of the Thames River.

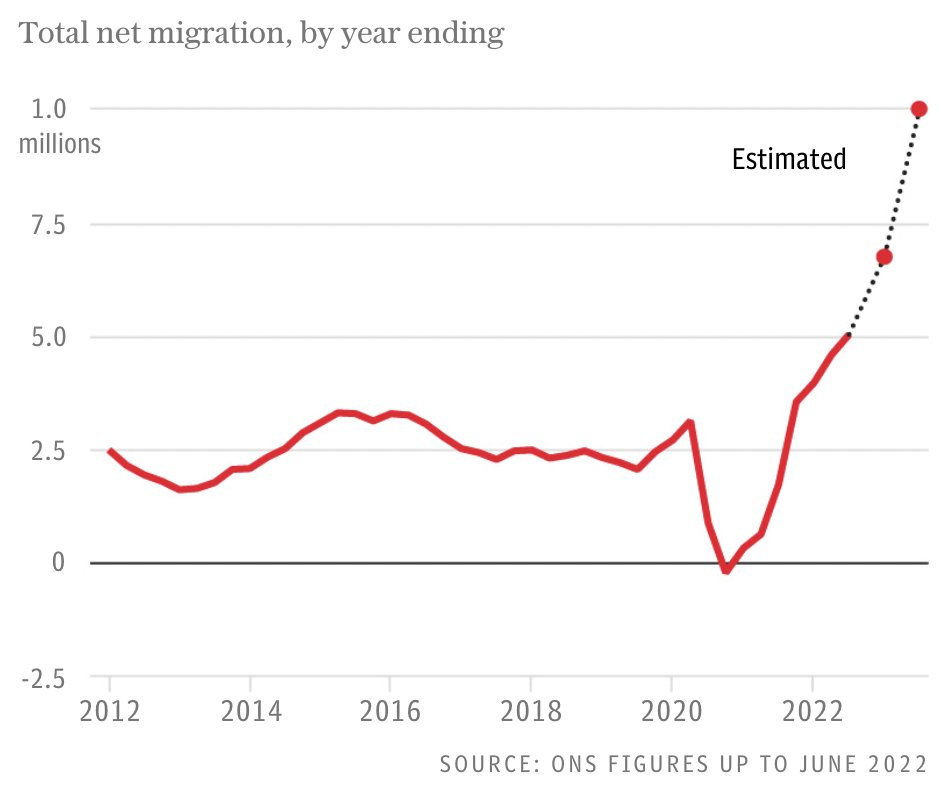

This strategy may make sense to some, but its impact has been horrific for most others. The cost of the living in the UK has skyrocketed, an increasingly-worse housing crisis plagues the land (compounded by the persistence of mass migration), leaving Britons in a state of malaise and dejection, seeing little good in the country’s future. A palpable sense of despair has set in.

I want to share two articles with you on this subject. The first comes from German outlet Der Spiegel:

Things aren’t going well for the United Kingdom these days. For the past several months, the flow of bad news has been constant, the country’s coffers are empty, public administration is ineffective and the nation’s corporations are struggling. As this winter came to an end, more than 7 million people were waiting for a doctor’s appointment, including tens of thousands of people suffering from heart disease and cancer. According to government estimates, some 650,000 legal cases are still waiting to be addressed in a court of law. And those needing a passport or driver’s license must frequently wait for several months.

Boarded up windows and signs reading "To Let" and "To Rent" have become a common sight on the country’s high streets, while numerous products have disappeared from supermarket shelves. Recently, a number of chains announced that they would be rationing cucumbers, tomatoes and peppers for the foreseeable future.

Rationing was the state of affairs in the UK for the first decade or so after WW2. This is a regression.

The IMF has projected that the UK economy will be the worst performing of all developed countries in the world, and will be outperformed by heavily-sanctioned Russia.

But nowhere is the feeling of having "lost the future" stronger than in Britain, according to the public opinion pollsters from Ipsos. In 2008, the year of the banking and financial crisis, 12 percent of people in the UK believed that their children would be worse off than them. Now, that number is 41 percent, Ipsos has found.

One significant reason for that pessimism is the fact that many simply no longer trust their speechifying politicians in Westminster to get much done. The Tory party, which has been in power now for a dozen years, has gone through four prime ministers since 2016 alone.

The UK Tories have accomplished nothing, other than actually increasing the numbers of migrants in the UK, contra to the desires of the pro-Brexit voting bloc.

Brexit will serve as the “all purpose” battering ram for years to come, and even though there is some truth to it causing short-term economic problems in the UK, the reasons for the rot go much, much deeper than just that.

Blackpool, a city in the north, once the most popular holiday destination for Brits:

Over the phone, Cartmell – head of the local employment agency – had said: "Come to Bloomfield." This neighborhood in the south of the city, one of the poorest not just in the city, but in the entire country, is, he continued, the best place to see what has happened to Blackpool. "Just a couple of paces away from the sea, and you’re already in the middle of a Dickens novel."

Countless shops have closed their doors in recent years, with only bargain stores, cheap supermarkets and fast-food chains remaining. Almost all of the empty lots are filled with trash, while signs on the walls announce the spaces as perfect for advertising.

Not a pleasant place:

The city’s decline came in waves. Like other cities in northern England, Blackpool profited many centuries ago from the British empire’s involvement in trading slaves and other wares. The wealth of Lancashire County, where Blackpool is located, was primarily the result of the local textile industry. Following the deindustrialization of the north, mass tourism kept the city’s 140,000 residents afloat for a time. But budget airlines soon began flying to sunny southern destinations, and Blackpool has had a hard time competing.

And since then, the place has been left largely to its own devices. The young and energetic have left, while many who failed to make it elsewhere have come to Blackpool for old times' sake.

The city was already on its knees when the conservative-liberal government of David Cameron announced an era of austerity in order to recoup the fantastical sums the government had injected into the banking industry during the financial crisis. And there was hardly another area of the country that was hit as hard by the savings measures as Lancashire. Blackpool had to slash far more than a billion pounds in public spending, and there was little left over for the poor. The city then had to close its doors to holidaymakers for two years during the pandemic.

Today, Blackpool is a place of records. No other city in the country is home to as many run-down neighborhoods. The life expectancy of male residents is just under five years below the national average, while that for women is almost four years lower. Almost one in five residents suffers from what local doctors call "shit life syndrome," while anti-depressants are prescribed here twice as often as in the rest of the country.

For those of you who have been on this Substack for the past several months, you already know that I have visited “The Norf” and have written about it. I decided to conduct some field studies in places like Manchester, Preston, and Blackpool. The portrayal of Blackpool in this Der Spiegel piece is accurate, and reflects not just my experience, but also what locals told me, from the bartenders/servers all the way up to city officials.

Read the rest of the Der Spiegel piece to see how the National Health Service (NHS) is collapsing, how hunger is now becoming a visible problem in parts of the country, and how the existing housing stock is not only shoddy, but unhealthy (black mold).

Where the above piece profiles today’s bleak UK from the contemporary street level, Samuel McIlhagga takes a long-term historical view to help us understand the forces that have caused this national malaise. This is a very long piece, but there are some excellent bits that I have to share with you. He also agrees with my contention that the British ruling classes have lost interest in actual governance (including their traditional role in shepherding the lower classes), in favour of the pursuit and even more importantly, maintenance of personal wealth.

British institutions exert impressive amounts of soft power for a tiny island nation. One can think of the country as playing the role of an Italian city-state in the fourteenth century: it capitalizes on historic cultural prestige, educates the children of elites from its former empire, and serves as a playground for wealth and status games while not really producing anything of hard value.

The overall trajectory becomes obvious when you look at outcomes in productivity, investment, capacity, research and development, growth, quality of life, GDP per capita, wealth distribution, and real wage growth measured by unit labor cost. All are either falling or stagnant. Reporting from the Financial Times has claimed that at current levels, the UK will be poorer than Poland in a decade, and will have a lower median real income than Slovenia by 2024. Many provincial areas already have lower GDPs than Eastern Europe.

While all of Europe is getting poorer and weaker as the twenty-first century progresses, the UK is unique in its relative incapacity and unwillingness to find solutions in comparison to peer nations like Germany and France. This is a process that has been gathering pace for centuries, stretching back to trends that began in the 1700s even as its empire was still expanding.

McIlhagga zones in on the lack of emphasis on technological schooling for UK elites being the main reason why the Brits fell behind the Germans and the French by the end of the Victorian Era.

Coasting on glorious past and its legacy:

Because of its status as an initially advantaged first mover, the UK now has a fortified elite content to live on the rents of bygone ages. Its social order is constituted by the cultural legacy of the old aristocracy, underwritten by London financial brokers, and serviced by a shrinking middle class. Its administrative and political classes developed a culture of amateurism, uninterested in either the business of classically informed generalism or that of deep technical specialism. The modern result is a system that incentivizes speculative, consultative, and financial service work over manufacturing, research, and production.

To the extent that the UK is governed by a partnership between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, it is an aristocracy that is not aristocratic and a bourgeoisie that is not productive. The old administrative upper class no longer wields power through land or patronage. The commercial middle class produces little of innovative value, its most prestigious sector being the servicing of other states’ surplus funds through family offices and merchant banks in London.

Despite being the hegemon of the industrial age, Britain never developed the mechanisms that allowed the U.S. and Germany to overtake it in the late nineteenth century in chemistry, transportation, labor productivity, and organizational methods. London’s first-mover benefits turned into profound disadvantages. It is not that Britain is sick, so much as that British elites are like aged pensioners: overly successful in their heyday, they are now drawing down their last investments and savings while letting the country house crumble.

Many in the British government knew about the possibility of immense decline as far back as 1902, and yet made no attempt to change course that might risk the political order itself. It may take another hundred years, and the total breakup of the United Kingdom itself, for the country to feel the full effects of elite dissolution.

He goes on to explain how efforts were made to address this at the beginning of the 20th century, and after WW2 (and he even mentions Dominic Cummings’ recent attempts), but that they all failed to accomplish the righting of the ship.

UK elites vs. American elites:

What differentiated the British elite of this time from most of Europe was the embrace of capitalist production by much of its aristocracy. Despite disputes on protectionism, the emergent middle class never experienced the same level of conflict with the nobility as their French or American counterparts. Compare, for instance, the backgrounds of two elite class premiers: George W. Bush and David Cameron. Bush’s patrilineal great-grandfather Samuel P. Bush established the family’s political dominance through technical education and the management of a firm that manufactured steel railway parts.

In contrast, Cameron’s father, paternal grandfather, and great-grandfather were all Oxford-educated partners in the stockbroker’s firm Panmure Gordon & Co, while another Sir Ewen Cameron was chairman of HSBC. His maternal grandfather came from a family of minor titled gentry and military officers. The differentiating factor between the two major factions of the British elite was whether they derived rents from aristocratic land holdings or professional-class financial speculation. Neither built their fortunes on the industrial basis that enriched the Bush family and many of their American peers.

The British analogs of the Bush clan—manufacturing and infrastructure-owning families—were often nonconformist protestants excluded from the Church of England and thus from educational routes into administration and politics. Instead, they either collaborated with the state at a distance or sought to join it by phasing out manufacturing and using the profits to buy land and professional education. It was not until the late nineteenth century, by which time the UK was falling behind the U.S. and Germany, that non-elite merchants like the Liberal MP, Unitarian, and screw manufacturer Joseph Chamberlain found a way into political office.

The resulting British state was over-geared towards non-productive economic rent-seeking. In effect, Britain didn’t have an incentive to chase development for survival, because it was the dominant power of early industrialization. Consequently, it never produced an elite whose primary base of power and wealth was industrial production, and which thus had a strong stake in developing and maintaining an industrial society.

When it comes to governance, you’ve heard me ask “why bother getting into politics when you can get into banking or finance for 50 times the money, and with much less scrutiny?”:

While teaching PPE, Brinkmann saw changing incentives when it came to careers in public service: “What has shifted, at least since the financial crisis of 2008, is that people no longer want to go into politics. Instead, it’s finance and consultancy companies. You get a very small minority of students who want to go into the civil service…The civil service has lost its social status.” If brilliant Oxford and Cambridge figures like J.M. Keynes and Isaiah Berlin found themselves in the twenty-first century, it is unclear why they would still opt for government work instead of leveraging their intellects in the private sector.

and

“People from my background 30 years ago did go into the city,” I was told by Arthur Snell, a former diplomat who went on to work at an intelligence firm founded by Christopher Steele, the former Russia desk man at MI6. “But many joined the army and foreign office. Those professions were seen as part of the cultural norm…The British—or more narrowly English—elite, I think have largely given up on the idea of public service, with the possible exception of one or two bits of the army that are still posh.”

The verdict:

Just where the tipping point between gradual decline and sudden crisis ultimately falls is unclear. As long as London remains relatively prosperous, the British elite may continue to manage the UK’s decline for decades, even another century. There is a long curve of failure from successful re-foundation to state collapse. Britain’s governing classes saw the precipice in 1902, but instead allowed the soft power of their institutions to prevent course correction. They were content to utilize earlier successes and respected institutions for rent-seeking purposes. In the process, they lost everything.

The lesson of Britain is that the long-expected crisis that will act as a moment of reset never arrives. The decline is usually far bigger and more structurally locked-in than the more temporary moments of crisis reflect. Things go well enough for the people that matter and there are plenty of distractions for those who don’t. And eventually, you find yourself just another vassal state in a cold, grey ocean.

All the attempts at resetting the UK have failed as the pain on the elites has not been felt enough to make them buy into necessary reforms. A lack of national consciousness (in large part to the unique class structure of the country) only compounds the issue.

“I’m alright, Jack. Keep yer hands off of my stack!”

I can’t stop talking about Francis Fukuyama. Thankfully, I am not alone in this as others recognize his importance and influence in political philosophy and its application to today’s global affairs.

Nathan Pinkoski has written an excellent review of Fukuyama’s 2022 book “Liberalism and Its Discontents”, showing how the respected academic has proven quite slippery over the past three decades in his defense (and promotion) of liberal democracy that arose out of his seminal work “The End of the History and the Last Man”.

The charge:

To the general public, Francis Fukuyama’s name is synonymous with the “end of history” thesis, which contends that since the end of the Cold War and the fall of communism, liberal democracy is the only ideology that has a universal appeal. His detractors often accuse him of triumphalism, but Fukuyama’s argument was more sophisticated than they realize. Liberal democracy, Fukuyama held, was the only regime that satisfied most of the perennial desires of human nature, although there would be delicate and difficult trade-offs. Yet, strangely enough, his new book contains passages that sound just like the caricature his detractors attacked. Fukuyama’s defense of liberal democracy has changed, and in ways that reveal a fundamental transformation of American liberalism itself. The nuanced account of human nature has vanished, swept up in the absolutization of an “inner self,” the recognition of which forms the core of the new liberalism. Yet the most astonishing aspect of the change is Fukuyama’s altered stance toward the revolution of unlimited technological progress. The elder Fukuyama disregards the brakes that his younger self was at pains to set up.

Fukuyama vs. Nietzsche:

As the full title of his famous book—The End of History and the Last Man—indicated, the young Fukuyama was responding to Nietzsche’s accusation that the human type produced by democracy is the contemptible “Last Man.” A tepid hedonist, the Last Man has no longing for excellence and finds what is noble unintelligible. According to Nietzsche, democracy’s fatal flaw is not that it produces greater and greater inequalities, as the left thinks. Its fatal flaw is its drive toward equality: Democracy is synonymous with universally enforced mediocrity. Nietzsche’s argument drew from the tripartite division of the soul in Plato’s Republic. By closing off the human aspiration for greatness, egalitarian democracy may satisfy material desires, one part of the soul. It may even satisfy rationality, another part of the soul. But it fails to satisfy the thymotic or spirited part of the soul, which seeks excellence, honor, and glory. Men motivated by thymos will find democracy dissatisfying and revolt against it.

How Fukuyama tries to address thymos:

As for thymotic desire, The End of History reinterpreted it as a quest for “recognition.” Borrowing from the left-Hegelian Alexandre Kojève, Fukuyama cast human history as a struggle for recognition among human beings. Liberal democracy brings this struggle to an end by ensuring the mutual and equal recognition of everyone by everyone. At the end of history, wars and conflicts would still happen, but they would be couched in the ideological language of liberal democracy, of mutual and equal recognition. NATO justified its military operations against Serbia by invoking the need to protect the human rights of ethnic minorities in Kosovo and ensure their democratic right to self-determination. Russia justified its military operations in Georgia and Ukraine as necessary to protect the human rights of Russian-speaking ethnic minorities and secure their democratic rights to self-determination.

Fukuyama relied on human nature to hedge against the threat of mediocrity that liberal democracy’s emphasis on equality would inevitably result in:

Although Fukuyama defended the idea of a universal, progressive history, he also—like Strauss—relied on the permanencies of human nature to serve as ballast, and, again like Strauss, assumed that these permanencies were resilient. Fukuyama also conceded that the liberal democratic solution to thymotic competition—a politics of universal recognition—wasn’t exactly the most ennobling civilizational picture. Something great would be lost. In this respect, Nietzsche was right.

In his new book, Fukuyama takes aim at both the left and the right:

At first glance, Liberalism and Its Discontents appears to repeat the concerns of the younger Fukuyama. This new book, like its predecessors, criticizes the excessive individualism manifest in neoliberalism and laments the turn away from public-spirited civic nationalism. Fukuyama takes aim at the economic agenda of right-liberals, which accelerates the depletion of social capital. The younger Fukuyama warned that the right, despite its socially conservative base, embraced the language of “no limits” in the sphere of economics. This commitment led the right to become overly suspicious of the state and of laws regulating and organizing economic activity.

Liberalism and Its Discontents also addresses the excessive individualism of the left, the exaggerations of identity politics that look for systemic racism and patriarchy in every social interaction. This kind of activism implies that civil society is itself unjust, deepening “liberalism’s tendency to weaken other forms of communal engagement” and destabilizing civic virtues. The younger Fukuyama made similar arguments. He contended that the left’s individualist excesses undermined the social capital required to build high-trust societies, which are the societies that sustain liberal democracy.

On closer inspection, Fukuyama has changed:

Yet in other respects, Fukuyama has changed. His critique of the left has become much more muted. In the past, he criticized “innovations like bilingualism and multiculturalism,” which, instead of aiming to assimilate newcomers, decrease the stock of social capital by “erecting unnecessary cultural barriers.” These policies were, he said, part of a regrettable trend of recognizing an “ever-widening sphere of individual rights at the expense of community.” In Liberalism and Its Discontents, however, he attacks rightist figures such as Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule for challenging the “expanded realm of individual autonomy.”

It is odd that Fukuyama singles out Deneen and Vermeule. In the 1990s he had already made the arguments for which they are known today. Fukuyama argued then that the modern left’s embrace of personal autonomy and attacks on limits did not actually challenge capitalism. Instead, they intensified the most individualistic elements of capitalist culture that ravage civil society. That is in large part what has happened in the West since the 1960s. In May 1999, writing in The Atlantic, Fukuyama argued that “the culture of individualism, which in the laboratory and the marketplace leads to innovation and growth, spilled over into the realm of social norms, where it corroded virtually all forms of authority and weakened the bonds holding families, neighborhoods, and nations together.” The consequence of the triumph of personal autonomy has been “a rise in crime, broken families, parents’ failure to fulfill obligations to children, neighbors’ refusal to take responsibility for one another, and citizens’ opting out of public life.”

In these passages, the younger Fukuyama sounds more socially conservative than Patrick Deneen.

Technology and Reason do not go hand in hand:

Fukuyama’s new framework cripples his capacity to reflect on the political and moral limits of technological progress, and on how technology relates to liberalism. That handicap manifests itself in what might have been the most intriguing part of Liberalism and Its Discontents, the chapter on technology, privacy, and freedom of speech. How is it, Fukuyama asks, that the misleading content widespread on social media is, despite its unreliability, so popular? Its popularity seems, he concludes, to result from “motivated reasoning”: the tendency of human beings to pick the reality they prefer. This kind of reasoning is in tension with liberalism, which depends upon “public reason” based on shared facts.

The younger Fukuyama might have grappled with a disquieting possibility: that the rise of divergent “realities” within the leading liberal democratic countries in the West suggests that liberalism’s success was never really founded on a scientific, rational Enlightenment culture. Rather, it depended on technological advances that created a particular media culture. This print culture had a high bar of entry; it required literary skill and erudition, which in turn ensured a certain homogeneity among the participants. They agreed on norms that resisted censorship and upheld rights to publish and speak. In short, the norms that produce a free-speech society are downstream of the invention of the newspaper. Yet technological change, notably the proliferation of television and the internet, created new media with a lower bar for entry; and in the quest for audience, entertainment, sensationalism, or fandom, its participants produce alternative cultural narratives that fracture the body politic. Old norms, including the norms of free speech, get tossed aside. Liberalism’s fate is tied up with a historically contingent print culture. As that print culture goes, so goes liberalism. This is why some conclude that to hold mass democracy together requires a strong, postliberal hand.

The maintenance of liberalism requires illiberalism. “We cannot tolerate the intolerant.”

The elder Fukuyama, however, ignores such a troubling line of thought. Instead, he blames conservatives for ruining America. Liberalism and Its Discontents contends that right-wing ideology’s proliferation on the internet threatens “the foundations of liberal democracy.” (The internet behavior of the progressive left, he assures us, “does not threaten” these foundations.) Once, we were able to hold right-wing ideology in check; now, it’s much harder. The story he tells follows the script of today’s liberal establishment media:

Right-wing paranoia was always present in American politics, from the Red Scare of the 1920s to Joseph McCarthy in the 1940s, but such conspiracy theories were generally exiled. . . . [B]efore the internet, information was controlled by a small number of broadcast channels and newspapers. . . . [B]ut the internet has provided an unlimited number of channels for disinformation to spread.

Hence the “need” for the Censorship-Industrial Complex.

New “hate speech” legislation is making its way through the Republic of Ireland’s legislature. This legislation is very, very restrictive, punitive, and wide ranging. I cannot confirm the depiction of the legislation in this short piece by

and will rely on others more familiar with the specifics of the draft to help us understand what is being proposed.Can you see some of the problems with this law?

“Likely”, “possesses”, “hatred”, “with a view to the material being communicated”? Do you think these definitions will be abused?

As the Irish Council for Civil Liberties has pointed out, this new law says, in effect, “hatred is hatred”. One person’s idea of “hatred” is certainly not another person’s idea of “hatred”. That’s not a definition.

We also now have the situation where someone is criminalised for possession of hateful material “with a view to the material being communicated to the public or a section of the public”. It doesn’t matter if it is actually published or not. This is nothing less than “thought crime” (see 1984, Stalin’s USSR, Mao’s China etc).

It gets much worse:

“…the person shall be presumed, until the contrary is proved, ”

What just happened to “innocent until proven guilty”? That is perhaps the most fundamental principle of the justice system of any free society.

And how will they get this information? As Section 15 explains, they now have the ability to demand passwords to phones (“…any password necessary to operate it and any encryption key or code necessary to unencrypt the information accessible…any electronic means of information storage and retrieval”) at pain of imprisonment (12 months).

Frightening stuff. How would the courts treat this law, if passed? How would EU bodies that Ireland is a party to react to it if it becomes law?

For a mainstream look at the proposed bill, check out this piece in Euronews.

For those of you reading my series on Colour Revolutions and Regime Change, the following three letters, NGO, automatically make you question “where does their money come from?”

This is a natural impulse in light of how the sprawling NGO sector has served corporate and foreign interests across the globe, working as an end-run around democracy. For the normie, “NGO” suggests community-activism on the street level, altruistic in purpose, and locally organized. For the more savvy, it represents how governments, corporations, and billionaires influence politics and society through their wealth, via organizations that are unchecked by the democratic process.

More and more people are getting hip as to what the largest and most important NGOs are about, which is why more and more people are questioning their sources of funding. NGOs involved in politics will always demand ‘transparency’ on the part of their targets, but proposed new rules for transparency of NGOs operating in Europe has put that sector on the defensive, as

explains:Why would Non-Governmental Organisations who swear on the bible of transparency object to the Defence of Democracy Package proposed by the European Commission? After all the principal aim of this proposal is to shine the light of openness on the activities of NGOs funded by foreign interests. The Commission’s proposal states that its aim is ‘protect our democracies from entities funded by or linked to third countries and exercising economic activities in the EU that may impact public opinion and the democratic sphere. It will also aim to promote free and fair elections, to strengthen civil society and civic engagement’.

Writing in Politico, Eleanor Brooks and Israel Butler of Liberties, a German based NGO, argue that law requiring foreign NGOs to register and acknowledge the sources of their funding represents a threat democracy. They believe that the maintenance of a ‘free civil society’ requires that NGOs in receipt of foreign funding should be free from the burden of transparency.

An open and shut case, really. The Americans have required this transparency since 1938:

Brookes and Butler warn that ‘the Commission’s proposed rules adopt and legitimize the smear that CSOs are potential trojan horses for foreign governments’. Yet all these rules do is to alert the public to the fact that foreign funded organisations may promote interests that are at variance with those of the society within which they operate. The Foreign Agents Registration Act of the United States enacted in 1938 serves as a model in this respect. It requires organisations to periodically disclose their relationship with foreign principals as well as the funding they receive from abroad.

FARA like the Commission’s proposed legislation allows a nation’s citizens to know the source of the funding and influence exerted on public life. Transparency on this matter is no different to gaining clarity about the financial links between individual and corporate donors and political parties.

The NGO argument:

However, Brooks and Butler take the view that NGOs should be held to a different standard than other interest groups. They warn that ‘authoritarian leaders’ can ‘weaponize transparency restrictions’ and undermine public trust in the work of NGOS, which will make it ‘harder for them to fulfil their missions’.

A “mission” that evades transparency is automatically “covert” and falls within the realm of spying. Is this the actual position that they want to take?

The stand taken by Liberties is widely supported by their colleagues in the NGO industry. Over 200 NGOs have published a letter attacking the Commission’s proposals. The letter warns that such legislation can hurt the EU’s credibility to defend human rights abroad and embolden repressive leaders. From their standpoint, human rights can best be defended if NGOs are freed from having to account for their links to foreign sources of funding and foreign agencies. The reason why they take such strong exception to the Commission’s proposals is because they believe that if attention is drawn to their foreign affiliation and source of funding than their moral authority with the public will be undermined.

I guess they do want to take that position.

Most interesting of all is how they admit that transparency as to their funding negatively impacts the moral authority of their organization and its purpose(s).

They assert that only mean-spirited authoritarian governments can benefit from the Commission’s proposal. They seem to believe that since they are better at protecting democracy from authoritarian governments than a nation’s citizens, they should be exempt from public scrutiny. Liberties, the NGO which they represent received €700k from Open Society Foundations in 2021 and for the current year they have received over €600k from the EU CERV Operating Grant. Why should the world not know the source of their funding?

Hey look, it’s George Soros’ Open Society!

We end this weekend’s Substack with a look at “Big” Jack Zelig, a Jewish New York City gangster from the first half of the 20th century, when Jews and Irish gangsters were plentiful, often competing but sometimes cooperating with the Sicilian Mafia.

With the demise of Monk Eastman and Kid Twist, Big Jack Zelig, who had done stints in reformatories and prisons, was next in succession—though there were challengers—to head the Eastman gang. He had a tough and frequently mean crew watching his back that included “Whitey” Lewis (Jacob Seidenshner), Louis “Lefty Louis” Rosenberg, and Harry “Gyp the Blood” Horowitz (Gyp the Blood was infamous for his “skill” at breaking a man’s spine with ease over his knee). Zelig was smart and brought some efficiency, if you could call it that, to his “business.” Among the services he offered were: a knife slash on the cheek for up to $10; a bullet in the leg or arm for up to $25; throwing a bomb for up to $50; and murder for up to $100. He never lacked for clients willing to pay him and his boys. More importantly, he protected his territory against encroachment by other mainly Italian gangs.

Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

And don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes!

This upcoming week I will be publishing:

1. a new interview

2. a deep dive into Jake Sullivan's speech at Brookings re: new US Foreign Policy

and I will be appearing on a podcast.

Hit the like button at the very top of the page to like this entry and use the share button to share this across social media.

Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so (be nice!), and please consider subscribing if you haven't done so already.

...and don't forget to join me on Substack Notes - https://niccolo.substack.com/p/introducing-substack-notes