Saturday Commentary and Review #118

The USA's "Disinformation Complex", Resurrect the Polish-Lithuanian Union?, "Liberal Authoritarian" Dubai, Highways and Social Fabric, 17th Cen. Paris' 'Transfusion Affair"

Every once in a while, I try to think about how the first farmers in human history must have felt, when they mastered the rudiments of agriculture, freeing themselves from the precarious existence of hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Were they prone to idealist and utopian visions thanks to this massive technological breakthrough?

What of the first metal smelters? Did they convince themselves that they changed the world (or at least the conditions of their tribe) for the better? Is every technological breakthrough accompanied by utopian proclamations?

I’m old enough to remember the early World Wide Web and how it would revolutionize the world “for the better”. Information was to be “democratized”, leading to a better-informed citizenry, with access to information on a scale unimaginable only a decade prior. “Techno-Utopianism” was back, with the early architects of the internet patting themselves on the back for a job well done. “So what if the internet grew out of a US military research project? Look at what came out of it.”, was the refrain at the time.

Like all new technologies with great appeal, its original purpose was quickly shoved aside by monetization, something that the techno-utopians could live with (especially considering how much money many of them would make from it), and following that, weaponization. They did not lie about the “democratization of information”. This came to be proven correct, as anyone with an internet connection and a computer was able to access all sorts of information with only a few clicks, a far cry from visiting public libraries to root through shelves stacked with a very limited amount of books in comparison to what was on offer now on the web.

What was largely unforeseen was the collateral damage of this democratization of information: the collapse in both the trust of traditional mainstream media and the upending of its business model. People now had a powerful tool to use to critical analyze the media they consumed from mainstream sources, and more and more people found out just how manufactured traditional media was in terms of its output. This led more and more people to question the agendas of mainstream media outlets, precisely at the same time that it was being concentrated in fewer and fewer corporate hands.

The result of this process of discovery was that government and its corporate allies could no longer secure narrative control over events. This became a problem, a very significant one. The loss of narrative control meant that the model of manufacturing consent of the people was broken. Disruptive, non-mainstream media outlets and sources had to be quashed in order to to re-establish narrative control. This is why the “fight against disinformation” was born.

Jacob Siegel of Tabletmag has written not just the best piece of 2023 thus far, but also the most important one. I urge every one of you to read it in its entirety, because he has accurately analyzed the roots of the “disinformation fight”, how it was put together, rolled out, how it works, and most importantly of all, what it means for each and every one of us, especially you Americans. There is so much good stuff to excerpt from this piece, so I will limit myself to a few of the best morsels and once again insist that you read the whole thing:

For more than half a century, McCarthyism stood as a defining chapter in the worldview of American liberals: a warning about the dangerous allure of blacklists, witch hunts, and demagogues.

Until 2017, that is, when another list of alleged Russian agents roiled the American press and political class. A new outfit called Hamilton 68 claimed to have discovered hundreds of Russian-affiliated accounts that had infiltrated Twitter to sow chaos and help Donald Trump win the election. Russia stood accused of hacking social media platforms, the new centers of power, and using them to covertly direct events inside the United States.

None of it was true. After reviewing Hamilton 68’s secret list, Twitter’s safety officer, Yoel Roth, privately admitted that his company was allowing “real people” to be “unilaterally labeled Russian stooges without evidence or recourse.”

The Hamilton 68 episode played out as a nearly shot-for-shot remake of the McCarthy affair, with one important difference: McCarthy faced some resistance from leading journalists as well as from the U.S. intelligence agencies and his fellow members of Congress. In our time, those same groups lined up to support the new secret lists and attack anyone who questioned them.

When proof emerged earlier this year that Hamilton 68 was a high-level hoax perpetrated against the American people, it was met with a great wall of silence in the national press. The disinterest was so profound, it suggested a matter of principle rather than convenience for the standard-bearers of American liberalism who had lost faith in the promise of freedom and embraced a new ideal.

Formal origination:

In his last days in office, President Barack Obama made the decision to set the country on a new course. On Dec. 23, 2016, he signed into law the Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act, which used the language of defending the homeland to launch an open-ended, offensive information war.

Something in the looming specter of Donald Trump and the populist movements of 2016 reawakened sleeping monsters in the West. Disinformation, a half-forgotten relic of the Cold War, was newly spoken of as an urgent, existential threat. Russia was said to have exploited the vulnerabilities of the open internet to bypass U.S. strategic defenses by infiltrating private citizens’ phones and laptops. The Kremlin’s endgame was to colonize the minds of its targets, a tactic cyber warfare specialists call “cognitive hacking.”

Defeating this specter was treated as a matter of national survival. “The U.S. Is Losing at Influence Warfare,” warned a December 2016 article in the defense industry journal, Defense One. The article quoted two government insiders arguing that laws written to protect U.S. citizens from state spying were jeopardizing national security.

Privacy was now a threat to national security:

Lumpkin singled out the Privacy Act of 1974, a post-Watergate law protecting U.S. citizens from having their data collected by the government, as antiquated. “The 1974 act was created to make sure that we aren’t collecting data on U.S. citizens. Well, … by definition the World Wide Web is worldwide. There is no passport that goes with it. If it’s a Tunisian citizen in the United States or a U.S. citizen in Tunisia, I don’t have the ability to discern that … If I had more ability to work with that [personally identifiable information] and had access … I could do more targeting, more definitively, to make sure I could hit the right message to the right audience at the right time.”

The message from the U.S. defense establishment was clear: To win the information war—an existential conflict taking place in the borderless dimensions of cyberspace—the government needed to dispense with outdated legal distinctions between foreign terrorists and American citizens.

Since 2016, the federal government has spent billions of dollars on turning the counter-disinformation complex into one of the most powerful forces in the modern world: a sprawling leviathan with tentacles reaching into both the public and private sector, which the government uses to direct a “whole of society” effort that aims to seize total control over the internet and achieve nothing less than the eradication of human error.

Big Tech as Big Ally:

At companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Amazon, the upper management levels had always included veterans of the national security establishment. But with the new alliance between U.S. national security and social media, the former spooks and intelligence agency officials grew into a dominant bloc inside those companies; what had been a career ladder by which people stepped up from their government experience to reach private tech-sector jobs turned into an ouroboros that molded the two together. With the D.C.-Silicon Valley fusion, the federal bureaucracies could rely on informal social connections to push their agenda inside the tech companies.

In the fall of 2017, the FBI opened its Foreign Influence Task Force for the express purpose of monitoring social media to flag accounts trying to “discredit U.S. individuals and institutions.” The Department of Homeland Security took on a similar role.

At around the same time, Hamilton 68 blew up. Publicly, Twitter’s algorithms turned the Russian-influence-exposing “dashboard” into a major news story. Behind the scenes, Twitter executives quickly figured out that it was a scam. When Twitter reverse-engineered the secret list, it found, according to the journalist Matt Taibbi, that “instead of tracking how Russia influenced American attitudes, Hamilton 68 simply collected a handful of mostly real, mostly American accounts and described their organic conversations as Russian scheming.” The discovery prompted Twitter’s head of trust and safety, Yoel Roth, to suggest in an October 2017 email that the company take action to expose the hoax and “call this out on the bullshit it is.”

In the end, neither Roth nor anyone else said a word. Instead, they let a purveyor of industrial-grade bullshit—the old-fashioned term for disinformation—continue dumping its contents directly into the news stream.

It was then decided that more collaborators were needed:

It was not enough for a few powerful agencies to combat disinformation. The strategy of national mobilization called for “not only the whole-of-government, but also whole-of-society” approach, according to a document released by the GEC in 2018. “To counter propaganda and disinformation,” the agency stated, “will require leveraging expertise from across government, tech and marketing sectors, academia, and NGOs.”

This is how the government-created “war against disinformation” became the great moral crusade of its time. CIA officers at Langley came to share a cause with hip young journalists in Brooklyn, progressive nonprofits in D.C., George Soros-funded think tanks in Prague, racial equity consultants, private equity consultants, tech company staffers in Silicon Valley, Ivy League researchers, and failed British royals. Never Trump Republicans joined forces with the Democratic National Committee, which declared online disinformation “a whole-of-society problem that requires a whole-of-society response.”

The central tactic of this fight is to commit the crime that this mobilization is supposed to be countering:

Disinformation is both the name of the crime and the means of covering it up; a weapon that doubles as a disguise.

The crime is the information war itself, which was launched under false pretenses and by its nature destroys the essential boundaries between the public and private and between the foreign and domestic, on which peace and democracy depend. By conflating the anti-establishment politics of domestic populists with acts of war by foreign enemies, it justified turning weapons of war against Americans citizens. It turned the public arenas where social and political life take place into surveillance traps and targets for mass psychological operations. The crime is the routine violation of Americans’ rights by unelected officials who secretly control what individuals can think and say.

Total information control:

What we are seeing now, in the revelations exposing the inner workings of the state-corporate censorship regime, is only the end of the beginning. The United States is still in the earliest stages of a mass mobilization that aims to harness every sector of society under a singular technocratic rule. The mobilization, which began as a response to the supposedly urgent menace of Russian interference, now evolves into a regime of total information control that has arrogated to itself the mission of eradicating abstract dangers such as error, injustice, and harm—a goal worthy only of leaders who believe themselves to be infallible, or comic-book supervillains.

I wrote about “total information control” this past November:

Note this as well:

Something monstrous is taking shape in America. Formally, it exhibits the synergy of state and corporate power in service of a tribal zeal that is the hallmark of fascism. Yet anyone who spends time in America and is not a brainwashed zealot can tell that it is not a fascist country. What is coming into being is a new form of government and social organization that is as different from mid-twentieth century liberal democracy as the early American republic was from the British monarchism that it grew out of and eventually supplanted. A state organized on the principle that it exists to protect the sovereign rights of individuals, is being replaced by a digital leviathan that wields power through opaque algorithms and the manipulation of digital swarms. It resembles the Chinese system of social credit and one-party state control, and yet that, too, misses the distinctively American and providential character of the control system.

I wrote about how the USA has fundamentally shifted a little over two years ago:

Total information control, a changing country, and a foreign policy drive for global hegemony all add up to the essay of mine that I like to trot out most:

Read Jacob’s brilliant piece here in its entirety. As an added bonus, Tabletmag has also provided a “Disinformation Dictionary” which is not just a handy reference, but it also very funny.

With the neo-conservatives now holding the stronger hand in the internal debates at the White House regarding the war in Ukraine, they are thinking creatively on how to shore up their perceived gains once the war is ended.

Dalibor Rohac, a Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), has an idea: resurrect the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

AEI was neo-conservative ground zero during the Dubya years, pushing relentlessly for US military action in every spot on the globe that gained their attention. Attempting to re-order the world on US terms comes as second nature to them, which is why this ambitious proposal is completely within character for that think tank.

First, some background:

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would go on to become one of the largest countries in Europe and a fascinating laboratory of political governance, studied in some detail by the United States’ founding fathers, particularly in the Federalist Papers. After the end of the Jagiellonian dynasty, it transformed into an electoral monarchy, similar to the city-states of Italy yet operating on a vastly larger scale. The commonwealth’s legislature and local diets followed the principle of unanimity—not unlike the European Council does on many issues today. The commonwealth’s atmosphere of religious tolerance and freedom enjoyed by its nobility provided a stark counterpoint to the absolutist monarchies of Western Europe—not to speak of the tragic history that followed the commonwealth’s demise in 1795.

What if a similar political solution were available to the problems facing Ukraine and Poland today?

The argument for an explicit political union between the two countries is not based on nostalgia but on shared interests. To be sure, due to four centuries of common history within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, much of today’s Ukraine (and Belarus) shares far more of its past with Poland than it does with Russia, notwithstanding claims of Russian propagandists to the contrary and notwithstanding the fact that the relationship was oftentimes highly complicated, as illustrated by events of the 17th-century Deluge—most prominently by the Khmelnytsky uprising and its conflicting interpretations by Poles and Ukrainians.

Yes, regime change in Belarus is still on the menu, despite the catastrophic failure of the most recent attempt. Anyway:

Fast-forward to the present and to the near future, however. Both countries are facing a threat from Russia. Today, Poland is a member in good standing of the EU and NATO, while Ukraine is keen to join both organizations—not unlike the Grand Duchy of yesteryear, eager to become part of mainstream, Christianized Europe. Even if Ukraine’s war against Russia ends with a decisive Ukrainian victory, driving degraded Russian forces out of the country, Kyiv faces a potentially decades long struggle to join the EU, not to speak of obtaining credible security guarantees from the United States. The poorly governed, unstable countries of the Western Balkans, prone to Russian and Chinese interference, provide a warning about where prolonged “candidate status” and European indecision might lead. A militarized Ukrainian nation, embittered at the EU because of its inaction, and perhaps aggrieved by an unsatisfactory conclusion of the war with Russia, could easily become a liability for the West.

Imagine instead that, at the end of the war, Poland and Ukraine form a common federal or confederal state, merging their foreign and defense policies and bringing Ukraine into the EU and NATO almost instantly. The Polish-Ukrainian Union would become the second-largest country in the EU and arguably its largest military power, providing more than an adequate counterweight to the Franco-German tandem—something that the EU is sorely missing after Brexit.

Neo-conservatives can still not forgive France and Germany for opting out of the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Also note the concession that the UK was nothing but the Trojan Horse of the Americans inside of the EU. Rumsfeld called the Poles (and other willing collaborators of neo-conservatism in Europe) “New Europe”. Rohac is picking up on this theme by proposing this Polish-Ukrainian confederacy.

For the United States and Western Europe, the union would be a permanent way of securing Europe’s eastern flank from Russian aggression. Instead of a rambling, somewhat chaotic country of 43 million lingering in no-man’s land, Western Europe would be buffered from Russia by a formidable country with a very clear understanding of the Russian threat. “Without an independent Ukraine, there cannot be an independent Poland,” Poland’s interwar leader, Jozef Pilsudski, famously claimed, advocating a Polish-led Eastern European federation including Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine—basically a recreation of the medieval commonwealth.

As you can see, the entire point of this exercise would be to do what the Americans have been denying that they have been doing for decades now: surrounding Russia.

Unification-by-stealth?

This is not fantasy talk. Early on during the war, Poland passed legislation allowing Ukrainian refugees to obtain Polish ID numbers, giving them thus access to a host of social and healthcare benefits normally reserved for Polish nationals. The Ukrainian government vowed to reciprocate, extending to Poles in Ukraine a special legal status not available to other foreigners. With over 3 million Ukrainians living in Poland – including a sizeable pre-war population – the cultural, social, and personal ties between the two nations are growing stronger every day.

Very much a long shot, but one worth monitoring.

I really do not have much to say about the United Arab Emirates (and in particular, Dubai), as I have never set foot there and do not know much about it. Thankfully, Michael Anton has saved the day via a long essay detailing his recent visit there, and in particular how the Emirates are trying to square liberalism and modernity with their Islamic faith and traditions.

Our elites don’t despise the UAE nearly as much as they hate Hungary. For one thing, the former is not European and so is not blamed for departures from up-to-the-minute managerial woke orthodoxy, the same way that (for instance) Muslims in the West generally get a pass for not being down with the latest LGBTQ diktat. Another reason is money—and not just oil. The UAE, through its largest city Dubai, has placed itself at the center of a huge portion of the global economy. Dubai today is to the Middle East, much of Africa, and (increasingly) South Asia what Hong Kong has long been to the Western Pacific: the business, financial, and legal capital of the entire region. If you want to make money anywhere within a thousand miles, your quest inevitably will take you there—often. And since lots of people do, it pays to keep the cheap insults against your eventual hosts to a minimum.

This is not to say that the UAE gets a free pass. All the usual NGO complaints are made against the country, including human rights violations, draconian punishments, and lack of civil liberties. In addition, there is intense (if limited, because few care) anger at the UAE’s military interventionism, particularly in Yemen. Yet these charges—which are far from completely unfounded—do not result in the same level of Western hatred as for Hungary.

Whereas Hungary styles itself an “illiberal democracy,” the UAE’s system can be described as “liberal authoritarianism.” One may question how a state with an admitted lack of what we in the West consider core rights could be “liberal.” I’ll endeavor to explain.

…..

The United Arab Emirates is definitely undemocratic. Our hosts—officials from the unfailingly polite foreign ministry—liked to boast of the various assemblies and councils that vote on this or that. I have no doubt their pride was genuine and no wish to offend them, but the political scientist in me must call a spade a spade: the UAE is an authoritarian state. Everything of any importance is decided by the emirs at the local level and by the president (or “the sheikh,” as everyone calls him) at the national.

Some history:

A brief history lesson: the “emirates” that make up the UAE are seven hereditary tribal monarchies whose continuities date back to the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1971, Zayed bin Sultan, emir of oil-rich Abu Dhabi, welded six of them together, adding the seventh the following year, into the country we know today, and which he ruled until his death in 2004.

Those seven emirates are in, as they say, a rough neighborhood: the Arabian Desert behind them, the Persian Gulf in front, Iran looming to the north, a not-always-friendly Saudi Arabia to their west, and just to the northeast, the Strait of Hormuz—since the rise of the petro-economy, earth’s most important and contested chokepoint, through which passes a third of the liquid natural gas and a quarter of the oil the world consumes daily. When cash-strapped Britain informed the Gulf emirs that it would soon be withdrawing Royal Navy protection that had been guaranteed since shortly after World War I, Sheikh Zayed quickly concluded that the lightly populated and (then) defenseless emirates would be easy prey to Iran, and perhaps others. His answer was to unify along the lines of an ancient defensive league: strength in numbers at the national level, autonomy in domestic affairs. Originally, Bahrain and Qatar were to join as well but opted out at the last minute. Today, each emirate is akin to a U.S. state, with its own government, governor (emir), and local laws. Indeed, as I would learn somewhat to my dismay, federalism is healthier in the United Arab Emirates than in the United States of America.

Abu Dhabi’s dominance:

For one thing, the dominance of Abu Dhabi over the rest of the UAE is so complete that there is never any question but that the emir of Abu Dhabi will, perforce, be the sheikh of the entire country. It’s not just the oil, which Abu Dhabi has in abundance while the other emirates do not. (Dubai has a small amount, but oil now makes up less than 1% of its economy.) Abu Dhabi also accounts for 87% of the country’s land area, about a third of its total population, and nearly two thirds of its GDP. And everywhere you go, you are reminded that the founder of the country was an emir of Abu Dhabi descended from a long line of emirs of Abu Dhabi.

Flattering MBZ:

In my time in the Trump Administration, I had occasion to sit in on most of the president’s meetings with foreign leaders and to listen to nearly all such phone calls (standard practice in the national security bureaucracy). I therefore got to see and hear MBZ in action. He is, first of all, extremely amusing—in the way of a man who is comfortable with his place near or at the top of the world and who uses his sense of humor to lighten the mood and put those around him at ease. He is obviously smart and well informed. He not merely held his own in the conversations I witnessed with American officials; he ran circles around most of them.

In that first encounter, in May 2017, another aide who was in nearly all of those meetings with me leaned over and whispered, “Most impressive foreign leader I’ve seen yet.” I agreed. Many others do as well. Three years ago, the New York Times called MBZ the most powerful Arab ruler and one of the most powerful men on earth—this despite the UAE having a third as much oil as Saudi Arabia and less than a third of its population. Given the immense size of the UAE’s sovereign wealth funds, most of which MBZ controls, it may also make sense to consider him the world’s richest man. Sorry, Elon.

Economic diversification:

But the main driver of diversification has been the development of Dubai, already an important trading center, into a global business (and now tourist) hub. The Emiratis (or Sheikh Zayed) seemed to intuit that for the country to be anything more than a minor player, even in a region full of minor players, it would need more wealth, more technology, and thus more people—more than it could reasonably expect from natural population growth, at least in the medium term. Also, for whatever reason, native Emiratis prefer government or military service over private employment, so economic growth at the level the sheikh and the other emirs desire also requires expats. Thus, in a sense, did the whole country copy the “Dubai model” and open itself up to the world.

And the world came, and is still coming. A senior official in the UAE government told us that applications for residency permits exceed supply, allowing the government to be especially choosy.

Click here to read the rest, especially the bit about women in the UAE.

This edition of the weekend ‘stack is already rather long, so I will limit myself to only one excerpt from this excellent piece by Anton Cebalo (a friend of the FbF Substack) on how mid-century planners “demolished America’s social fabric”:

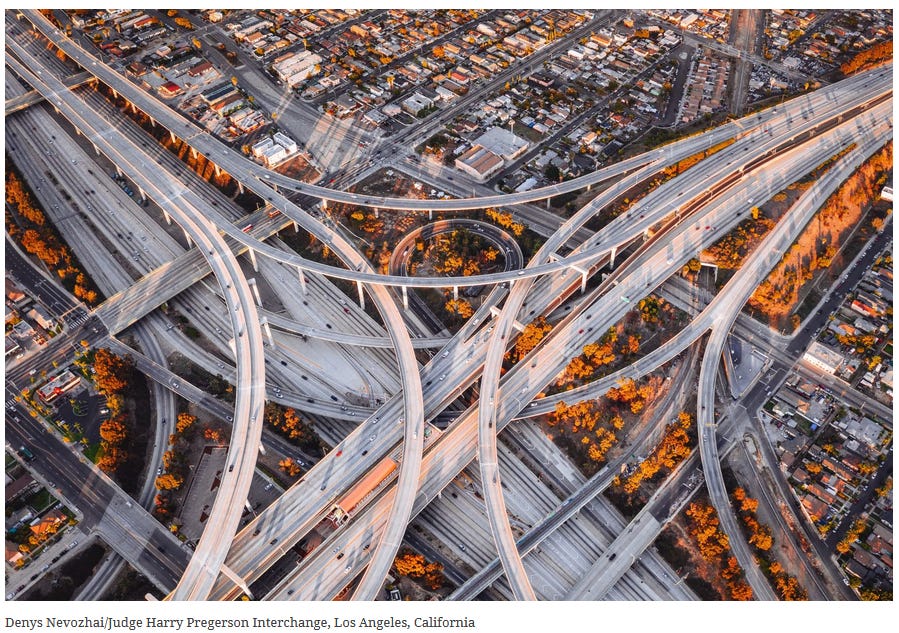

If the highway system only stopped at each city’s beltway, its praises would be more common today. Instead, it was conceived as if it were shaping an inordinate and malleable mass rather than lived space. The general pattern was often the same: highways cut through city downtowns so that the suburban consumer had easy access to its new shopping districts. Already existing local urban life and its communities were forced to give way to a speculative version of Norman Bel Geddes’s Futurama and its conveyor belt idea. Consequently, it was this conveyer belt, the highway, that caught the ire of the public.

Starting from the mid-1950s, the public began to make its opposition known in what are commonly known as the “highway revolts.” They were an open dispute over who would define America’s social sphere, but they also embodied organic elements of a civil society that is today sadly missing. Most major cities were embroiled in such conflicts by the late 1960s, opposing highways breaking up their downtowns and historic areas.

In California, such public opposition manifested in cities like San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, and San Diego as early as the 1950s. The disputes spread throughout the country. One famous struggle was in New Orleans, locally known as the “Second Battle of New Orleans.” In 1969, residents successfully thwarted the construction of the Moses-proposed Vieux Carré Riverfront Expressway: an elevated freeway that was supposed to cut through the city’s famous French Quarter. Other states like Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Florida, Ohio, Oregon, and others also saw intense public backlash which persisted well into the 1970s.

Published in 1961, The Death and Life of American Cities by Jane Jacobs is credited as a catalyst for these disturbances, as she spoke directly to the highway revolts in its opening pages. She stressed the street as crucial to healthy urban sociality, and that a “growing number of planners and designers have come to believe that if they can only solve the problems of traffic, they will thereby have solved the major problem of cities.”

The book is unabashedly polemical, taking aim at planners who sought to impose a “pretend order” which she said was derived from everything but the actual, lived world of cities themselves. She criticized the paternalistic “segmentation of life” that was part of their blueprints, as if it were an attempt to decontaminate the organic relations between different spheres of life. While she did not ascribe direct malice to the planners, it is remarkable how her words echo those of Moses’s some 20 years before—when he was waging a public war against Tugwell, appealing to the man in the street against bureaucratic utopian projects.

Click here to read this essay in its entirety.

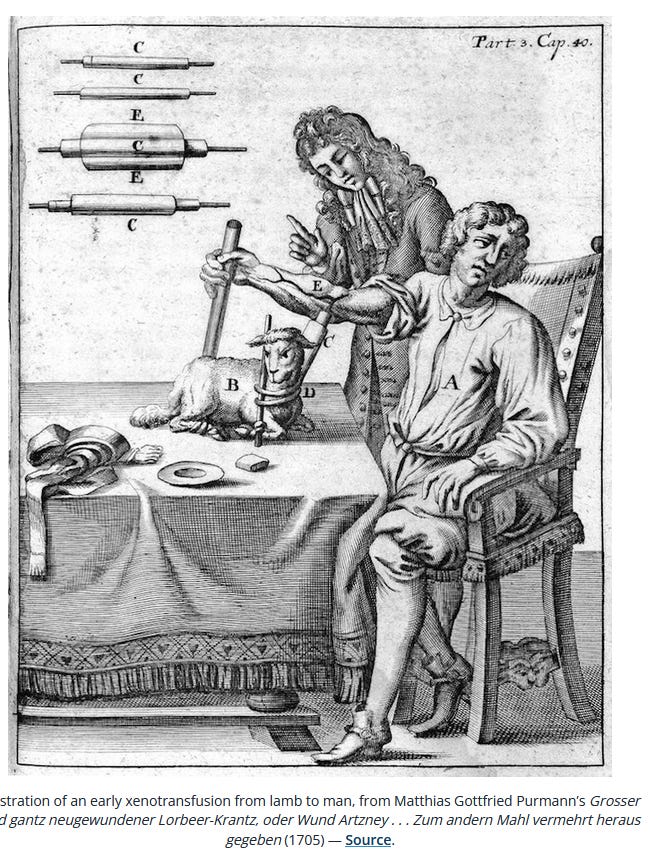

We end this weekend’s Substack with a bloody affair: how medical experiments in 17th century Paris saw a surgeon and a physician “….transfusing the blood of calves and lambs into human veins held the promise of renewed youth and vigour”.

Beginning in the spring of 1667, public opinion in Paris was rocked by a remarkable affair involving domesticated animals: the first practical experiments to transfuse animal blood into humans for therapeutic purposes. The experiments that came to be known as the “Transfusion Affair” were shrouded in the competing claims of a highly public controversy in which consensus and truth, alongside the animal subjects themselves, were the first victims. “There was never anything that divided opinion as much as we presently witness with the transfusions”, wrote the Parisian lawyer at Parlement, Louis de Basril, late in the affair, in February 1668. “It is a topic of the salons, an amusement at the court, the subject of philosophical dissertations; and doctors talk incessantly about it in all their consultations.”1

At the center of the controversy was the young Montpellier physician and “most able Cartesian philosopher” Jean Denis, recently established in Paris, who experimented with animal blood to cure sickness, especially madness, and to prolong life. With the talented surgeon Paul Emmerez, Denis transfused small amounts of blood from the carotid arteries of calves, lambs, and kid goats into the veins of five ailing human patients between June 1667 and January 1668. Two died, but three were purportedly cured and rejuvenated.2 The experiments divided the medical establishment and engaged a Parisian public avid for scientific discoveries, especially medical therapies to cure disease and to stay forever young.3

Interesting stuff. Click here to read the rest.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

The article about disinformation hits very close. The people who I know are involved with the disinfo industry are generally young women who would've gone into HR 5 years earlier. Ghastly little tyrants they are, I'm sure you know the type. Conform to the stereotype almost to the T. SSRI-eyed college graduates with little concern for truth or justice.

At least during the totalitarian regimes of the early 20th century they were honest about what they were. Some apparatchik working at the ministry of public enlightenment could be pointed out. They knew what they were. Our modern "disinformation experts" genuinely believe that they are objective and true. I can hardly think of people I hate more as a group than they.

There are no available means to counter the disinformation complex beyond a neo-Luddite avoidance of all media and social media. You can't argue with believers and it is a waste of energy to apply formal logic to any exchange in which at least one party is emotionally engaged. Artistic/aesthetic resistance via meme-warfare is possible but runs phenomenal risks as Douglass Mackey (Ricky Vaughn) has found.

We are now seemingly trapped within a giant digital pain box.