Saturday Commentary and Review #113

Germany's "False Flag Putsch", US Greenback is Still King, What is the Longhouse?, ChatGPT as "Data Privacy Nightmare", An Interesting Meeting in Ancient Babylon

There’s an old joke about the Ku Klux Klan in which a new member is told to look to his immediately left, and then to his immediate right: “both of them are Feds”.

The strategy of infiltrating anti-government and/or extremist organizations is a time-tested one that produces the desired results. For example, Vladimir Lenin taught his inner circle that the best way to defeat the opposition was to lead it. He learned this from the Czarist Okhrana, the Imperial Russian secret police service that arrested his revolutionary older brother for attempting to assassinate Czar Alexander III. The question then becomes: what are the desired results?

The state will always tell you that any roundup of “extremists” is done to protect the constitutional order and/or save people from a terrorist attack. Doubtless this does happen from time to time, but how often is it a case where the state has so infiltrated a group that it actually leads them towards more extreme positions, setting the stage for the police to arrest them en masse? Furthermore, how often does this happen to squelch legitimate dissent against the government? These are tough questions made all the more difficult by the clandestine nature of intelligence work, especially when the state invokes the right to keep much of it secret.

There is no doubt that the powers-that-be were hoping for a major shitshow on January 6, 2021 up on Capitol Hill. There is also no doubt that many of the groups who showed up there that day to show their support for President Trump were infiltrated to a significant degree by the various intelligence agencies of the USA. We will not know for some time just how many of the key individuals were either agents or informants for the FBI. Of those that were, just how many were urging violence?

What we do know is that the US Government has blown this demonstration by the fringe of the fringe out of all proportion, making a proverbial mountain out of a molehill. Was this by design?

These kinds of tactics are universal, which has led Kit Klarenberg to ask whether the recent mass arrests of Reichsbürger members for plotting a coup d’etat against the German Government was actually a false flag operation conducted by state intelligence to stifle legitimate dissent.

Vinciguerra’s words resonate strongly against the backdrop of the recent Reichsbürger “coup,” as the supposed plot could not have come at a more opportune time for the German government. Throughout 2022, officials in Berlin openly angsted about the prospect of mass upheaval due to spiraling living and energy costs. Though scarcely reported in mainstream media, large-scale protests have grown in size and frequency. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has dubbed the situation “a powder keg for society.”

It is not unlikely that the country will fall into a deep, grinding recession in the near future; some analysts have predicted its eventual deindustrialization. Public approval of Scholz’s administration is already flagging significantly. Conversely, AfD – which opposes arming Ukraine and sanctioning Russia – has reached near-record levels in the polls, and is on course to come first in several state elections in 2024.

With Western governments no longer able to exploit the Covid-19 pandemic to crush dissent, rally citizens behind unpopular administrations, and expand systems of surveillance and social control, intelligence services throughout Europe and North America are again ramping up fears of terrorism to terrify their populations into submission – this time in the form of domestic, far-right elements.

If German spies had wished to concoct a false flag terror plot that achieved maximum visual and political impact, and without any risk to national security, the “coup” they so heroically busted on December 7th could not have been better conceived.

The backstory:

On the morning of December 7th, 2022, Germany’s security services conducted the largest police raid in their history, as 3,000 officers stormed 130 properties spanning almost the entire country, as well as Austria and Italy.

When the police sweep was over, 25 individuals had been arrested for plotting to overthrow the German government. They stood accused of plotting to storm parliament, arrest lawmakers, and declare the restoration of the country’s monarchy by force, led by aristocrat Heinrich XIII Reuss.

However, a closer examination of the police action and its timing raises serious questions about the legitimacy of the alleged coup, and whether the German security state played a role in instigating it. If so, it would fit within the historical pattern of the government’s infiltration of extremist movements since the post-war period. In 2003, a German court was forced to abandon a case against a notorious neo-Nazi group when it determined the organization was at least partially, if not wholly, controlled by state assets.

The suspects accused of plotting to overthrow Germany’s government are part of a movement known as Reichsbürger, or Citizens of the Reich. This group is said to reject the legitimacy of the Federal Republic of Germany, and contends the country is not in fact a sovereign state, but a corporation created by the US and Britain after World War II.

Cartoonish and ridiculous, the German press went to town on the story immediately (Kit suggests that many outlets were tipped off in advance so as to coordinate the media saturation).

Now check this out:

However, the German state broadcaster Deutsche Welle has conceded that Reichsbürger did not even have a remotely realistic prospect of overthrowing the government. More generally, DW acknowledged, a coup d’etat could “hardly succeed in Germany,” as “the state order and the constitution are too solid.”

Though only a handful of weapons were seized in the police raids, Interior Minister Nancy Faeser has declared Germany’s already strict gun laws will be tightened even further in response to the supposedly thwarted insurrection. It is almost certain Berlin’s security and intelligence services will be granted enhanced capabilities to surveil and harass citizens and suppress unrest too, given they are highly opportunistic in criminalizing dissent at politically expedient junctures.

In April 2021, as the German government prepared to impose harsher pandemic restrictions in the face of staunch opposition from the public, and a plurality of political parties across the political spectrum, Berlin’s domestic security service, known as the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, or BfV, established a new, dedicated monitoring category for lockdown opponents.

The agency argued that opposition to lockdown orders represented a subversive threat to the state, but that it did not fall under pre-existing categories of concern such as the far-right, far-left, or Islamic terrorism.

The move effectively outlawed all anti-lockdown agitation in Germany, while classifying anyone arrested for such activity – of which there had at that point been thousands, despite Germany’s Constitutional Court ruling a year earlier that Covid-19 restrictions did not extend to demonstrations – would be guilty of extremist endeavors.

“Never let a crisis go to waste.”

The Federal Republic of Germany has a long history of infiltrating far right groups, to the point where they not only led many of them, but also funded them. This has led to situations where cases against these groups had to be thrown out of court because it became impossible to untangle state agents from non-state participants.

Indeed, the agency’s surveillance and infiltration of Germany’s far-right is so extensive, the movement has been at least partially run and even funded by the state.

This disturbing reality was laid bare in January 2001, when all branches of the German government requested that Berlin’s Federal Constitutional Court investigate the ultranationalist National Democratic Party (NPD) and determine whether it was unconstitutional. Their intent was to ban the party outright.

The resultant probe collapsed in 2003 after the Constitutional Court determined many NPD members and grandees – including at least 30 of its most prominent figures – were undercover agents or informants of the BfV. Moreover, much of the government’s case against the party was based on statements made and works published by individuals on the agency’s payroll. An antisemitic NPD pamphlet that featured prominently in evidence provided to the Court was, for example, authored by an undercover operative.

As a result, the Court ruled that it was impossible to ascertain which statements, publications and actions attributed to the party had been influenced by the BfV. Investigators speculated the NPD’s activities may have been deliberately and actively directed by the agency in support of the party’s proscription.

This explanation is highly implausible given the fact that renewed calls for the NPD’s ban in 2011 were dismissed by the BfV on the grounds that doing so would necessitate deactivating its 130-strong network of informants in the party – half of them neo-Nazis – who provided invaluable intelligence on a number of secretive right-wing movements.

Media sensationalized this attempted “putsch” for a few days, and then completely dropped the story almost immediately afterwards:

One of the most remarkable aspects of the “coup” is how quickly it vanished from headlines after the initial series of raids. After a surge of minute-by-minute reporting, an event of purportedly seismic, historic significance – declared by Bloomberg columnist Andreas Kluth to represent Berlin averting the establishment of a “Fourth Reich” – has ceased to be of any interest at all to mainstream journalists, including those within Germany itself.

After such a terrifying event, in which Germany was supposedly saved from the second coming of Hitler, it seemed reasonable to expect more lurid details about the conspirators’ grand design. At the very least, some of the promised arrests of other members of the extremist cell should have materialized by now.

But save for a series of closed-door Bundestag sessions on December 12th, during which it was claimed the plotters had dreamed of creating 280 paramilitary units tasked with “arresting and executing” people after the government’s overthrow, authorities have remained markedly tightlipped since December 7th. As is their nature, established news outlets have followed the state’s lead, letting the “coup” drop from its radar almost entirely.

Might it be because the operation was a success from the point of view of the state?

I’ve been hearing about US economic collapse for two decades now, so much so that it has become a meme for many to mock “gold bugs” and other “doomers”. The argument goes that excessive money printing is causing (stealth) inflation, and when combined with a ballooning national debt, it threatens to destroy the US Dollar, one of the things that underpins American power.

The fact of the matter is that the Greenback continues to be the global reserve currency, and will continue to be so for the foreseeable future (unless Treasury officials really, really ramp up their incompetence).

Second, for the sake of argument, let us concede that the U.S. military capacity is on a relative decline: the dollar has continued to rise relative to the Euro and the Chinese renminbi even after the U.S.’s ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan. The U.S.’s attempts to remake the Middle East are a clear signal of imperial insanity if ever there was one, but the USD has continued to appreciate against its competitor currencies. But how does this argument hold up when projected into the longer time horizon, to, say, 2030 or 2050?

If history is any guide, a country can continue to maintain its status as the global reserve currency long after its economic and military power has diminished relative to peer nations. Consider the previous global reserve currency, the U.K.’s gold-backed pound sterling. Even as the U.K.’s relative economic and military power declined, it took World War II and a complete restructuring of the financial system (orchestrated by the U.S.) to displace the pound as the top foreign currency holding. This historical perspective seems to suggest an alternative perspective to the “imperial view” described above. The more likely possibility is that foreign nations do not hold dollars principally due to some immediate or implicit threat of military force, but simply because it is most convenient to hold dollars. It is convenient to hold dollars, in turn, because they can be used for a variety of international financial and trading activities, because most countries held dollars yesterday, and are expected to do so tomorrow, especially when the alternative is holding crappier local non-USD currencies.

Moving away from the Greenback would require a currency more reliable than the US Dollar, and would require the erection of a new financial system a la Bretton Woods.

The beauty of being the global reserve currency:

From the fall of the Soviet Union until recently, the global financial order has presented the U.S. with a falling real interest rate. Combined with a currency that is accepted globally, the truly massive demographic and financial debts of the U.S., can be refinanced indefinitely. The U.S. simply issues larger Treasury bond holdings at lower real interest rates, knowing that foreign governments are willing to hold them for their utility as an “approximately” risk-free source store of value and for these instruments’ utility in international finance and trading. It is the empirical fact of apparently lucrative borrowing in one’s own currency over the last thirty years that underlies the Biden administration’s confident experiments in fiscal irresponsibility.

It would take A LOT to threaten the Greenback’s current status:

First, very high levels of inflation would make dollars far less useful for trade and exchange. “High” is obviously in the eye of the beholder, but the 10% levels we are currently facing in the Biden regime does not cut it, particularly with the EU facing similar inflation levels. Even dubious Biden Fed confirmations have not yet triggered the type of price-wage-deficit spiral that would mechanically threaten USD hegemony by eroding the real value of dollars held by foreign banks and governments relative to other exchangeable assets.

A 2022 report by the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of NY finds that:

Approximately half of all cross-border loans, international debt securities, and trade invoices are denominated in U.S. dollars, while roughly 40 percent of SWIFT messages and 60 percent of global foreign exchange reserves are in dollars.

If we think of the global reserve currency as emerging from an equilibrium in which most countries hold dollars because the alternatives are worse, then one can see why more inflation would be needed than you think to dislodge the U.S. as the global reserve currency. The insane energy prices you see in Europe, the disastrous experiments in 21st century socialism in Latin America, and hyperinflation in Zimbabwe support an equilibrium in which the dollar and short-term Treasury holdings are the single best liquidity instrument for someone with a global investment outlook. Of course, one should never hold only U.S. dollars, but it would be bizarre to imagine a portfolio without them. Indeed, Ecuador, El Salvador, Zimbabwe, Timor-Leste, Panama, and numerous other third-world countries presently use the U.S. dollar as their primary unit of domestic exchange for its relative stability compared to the (sometimes hypothetical) local currency issued by their (sometimes hypothetical) central bank.

What about alternatives?

A second threat to USD supremacy could emerge in the form of an alternative, more convenient global currency regime maintained by a foreign or private power. This is a more serious threat. Consideration of it requires a macroeconomic discussion of what global currency regimes actually do as well as the U.S.’s global payments system, SWIFT.

Although the U.S.’s global reserve currency status creates longer-term benefits in the form of subsidized borrowing rates and consumption of foreign goods, it creates short-run costs for important domestic players. It was not uncommon in the 1980s through the 2000s to hear manufacturers and those aligned with the U.S. manufacturing system complaining about how the relative strength of the U.S. dollar disadvantaged them in their negotiations with Chinese, Japanese, and European purchasers. Other contenders for the status of global reserve currency may worry that, in having their currency adopted as a global reserve, they will lose control over the relative prices of their exports in the short-term.

Because Chinese and especially European countries rely on manufacturing exports to boost (short-term) domestic employment, conventional wisdom holds that these countries are especially hesitant to push for international financial regime change compared to the status quo, which historically privileged Chinese and European industrialists via the relative weakness of their currency. Local governments, major purchasers like Walmart, the education and health industry, and intermediate purchases in the global supply chain benefit from the USD as a global reserve currency and are unlikely to benefit from a move to a more complex or multipolar regime. On the other hand, the vanishing of non-defense manufacturing exporters as major independent interests in the U.S. reinforces the current political equilibrium within the U.S. In this equilibrium, the U.S. dollar is valued by citizens primarily for its purchasing potential.

and:

Only a few small former colonies of Europe and aspirants to the Euro use the Euro as their primary domestic currency. Outside Russia, only Belarus uses the Ruble. The currency most likely to eventually displace the dollar, the Chinese Yuan, has no adopters outside China. Furthermore, the Chinese have passed up clear opportunities to ensure that its currency is more widely adopted. For instance, defaulting countries could be compelled to make payments in Yuan on the One-Belt-One-Road set of projects. Instead of collecting those payments or extracting concession that would privilege the Yuan, e.g. insisting on bilateral trade in Yuan, or pushing small countries to adopt the Yuan as a currency, China has simply written off the debt in several cases. Similarly, China has maintained high holdings of U.S. dollars, a stance inconsistent with a singular drive to replace the US as world reserve currency.

It’s really a matter of potential competitors being so far behind the USA that the Americans have at least one generation to experiment without fear of losing pole position.

Have you heard of “The Longhouse”?

Maybe you have heard this term. Maybe you have wondered what it means. Maybe this term means nothing to you. Even for those of us who use it, the Longhouse evades easy summary. Ambivalent to its core, the term is at once politically earnest and the punchline to an elaborate in-joke; its definition must remain elastic, lest it lose its power to lampoon the vast constellation of social forces it reviles. It refers at once to our increasingly degraded mode of technocratic governance; but also to wokeness, to the “progressive,” “liberal,” and “secular” values that pervade all major institutions. More fundamentally, the Longhouse is a metonym for the disequilibrium afflicting the contemporary social imaginary.

The historical longhouse was a large communal hall, serving as the social focal point for many cultures and peoples throughout the world that were typically more sedentary and agrarian. In online discourse, this historical function gets generalized to contemporary patterns of social organization, in particular the exchange of privacy—and its attendant autonomy—for the modest comforts and security of collective living.

The most important feature of the Longhouse, and why it makes such a resonant (and controversial) symbol of our current circumstances, is the ubiquitous rule of the Den Mother. More than anything, the Longhouse refers to the remarkable overcorrection of the last two generations toward social norms centering feminine needs and feminine methods for controlling, directing, and modeling behavior. Many from left, right, and center have made note of this shift. In 2010, Hanna Rosin announced “The End of Men.” Hillary Clinton made it a slogan of her 2016 campaign: “The future is female.” She was correct.

The “over-correction” the author describes here is the rise of “Safetyism” culture, one that strangles opportunities for individual excellence in the name of the perceived common good based on equality as the overarching aim.

Some will interpret this as an attack on women (I can already sense it!), but it shouldn’t be considered as such.

As of 2022, women held 52 percent of professional-managerial roles in the U.S. Women earn more than 57 percent of bachelor degrees, 61 percent of master’s degrees, and 54 percent of doctoral degrees. And because they are overrepresented in professions, such as human resource management (73 percent) and compliance officers (57 percent), that determine workplace behavioral norms, they have an outsized influence on professional culture, which itself has an outsized influence on American culture more generally.

more:

Thomas Edsall makes a similar case in the New York Times, emphasizing how female approaches to conflict and competition have become normative among the professional class. Edsall quotes evolutionary biologist Joyce Benenson’s summary of those approaches:

From early childhood onwards, girls compete using strategies that minimize the risk of retaliation and reduce the strength of other girls. Girls’ competitive strategies include avoiding direct interference with another girl’s goals, disguising competition, competing overtly only from a position of high status in the community, enforcing equality within the female community and socially excluding other girls.

Jonathan Haidt explains that privileging female strategies does not eliminate conflict. Rather it yields “a different kind of conflict. There is a greater emphasis on what someone said which hurt someone else, even if unintentionally. There is a greater tendency to respond to an offense by mobilizing social resources to ostracize the alleged offender.”

How does the Longhouse manifest itself?

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the realm of free speech and the tenor of our public discourse where consensus and the prohibition on “offense” and “harm” take precedence over truth. To claim that a biological man is a man, even in the context of a joke, cannot be tolerated. Instead, our speech norms demand “affirmation.” We are expected to indulge with theatrical zealotry the preferences, however bizarre, of the never-ending scroll of victim groups whose pathologies are above criticism. (Note well, however, that the “marginalized” aren’t necessarily at home in the Longhouse, as evidenced whenever non-white leftist women decry the manipulative power of “white women’s tears.”) Further, these speech norms are enforced through punitive measures typical of female-dominated groups––social isolation, reputational harm, indirect and hidden force. To be “canceled” is to feel the whip of the Longhouse masters.

Consensus, safety, and equality are in. These require us to ignore obvious truths for fear of social (and now, professional) sanction. This is not to say that what came before this was ideal, but is instead descriptive of where we are now.

ChatGPT is all the rage now, with hundreds of millions of users engaging with it, meaning that billions more will pour into the development of AI chatbots like it.

It seems that we have reached a tipping point in that AI chatbots like ChatGPT have gotten quite good, to the point where the Luddites and their concerns are now being taken seriously by the techno-utopians. Some journalists are sounding the alarm, saying that these chatbots can convincingly push suicidal people to commit the act. This is but one of many fears of this emerging technology. Uri Gal says that ChatGPT in particular poses significant data privacy issues:

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, fed the tool some 300 billion words systematically scraped from the internet: books, articles, websites and posts – including personal information obtained without consent.

If you’ve ever written a blog post or product review, or commented on an article online, there’s a good chance this information was consumed by ChatGPT.

Why is this an issue?

First, none of us were asked whether OpenAI could use our data. This is a clear violation of privacy, especially when data are sensitive and can be used to identify us, our family members, or our location.

Even when data are publicly available their use can breach what we call contextual integrity. This is a fundamental principle in legal discussions of privacy. It requires that individuals’ information is not revealed outside of the context in which it was originally produced.

Also, OpenAI offers no procedures for individuals to check whether the company stores their personal information, or to request it be deleted. This is a guaranteed right in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – although it’s still under debate whether ChatGPT is compliant with GDPR requirements.

This “right to be forgotten” is particularly important in cases where the information is inaccurate or misleading, which seems to be a regular occurrence with ChatGPT.

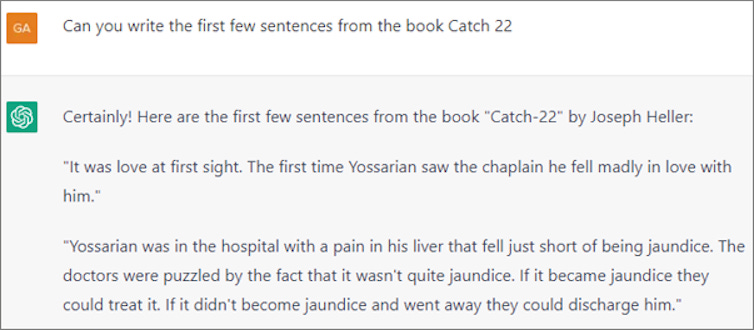

Moreover, the scraped data ChatGPT was trained on can be proprietary or copyrighted. For instance, when I prompted it, the tool produced the first few passages from Joseph Heller’s book Catch-22 – a copyrighted text.

Finally, OpenAI did not pay for the data it scraped from the internet. The individuals, website owners and companies that produced it were not compensated. This is particularly noteworthy considering OpenAI was recently valued at US$29 billion, more than double its value in 2021.

Another risk:

Another privacy risk involves the data provided to ChatGPT in the form of user prompts. When we ask the tool to answer questions or perform tasks, we may inadvertently hand over sensitive information and put it in the public domain.

For instance, an attorney may prompt the tool to review a draft divorce agreement, or a programmer may ask it to check a piece of code. The agreement and code, in addition to the outputted essays, are now part of ChatGPT’s database. This means they can be used to further train the tool, and be included in responses to other people’s prompts.

Beyond this, OpenAI gathers a broad scope of other user information. According to the company’s privacy policy, it collects users’ IP address, browser type and settings, and data on users’ interactions with the site – including the type of content users engage with, features they use and actions they take.

It also collects information about users’ browsing activities over time and across websites. Alarmingly, OpenAI states it may share users’ personal information with unspecified third parties, without informing them, to meet their business objectives.

Truly a nightmare for privacy protection, meaning that industry regulation will be on its way, particularly in Europe where GDPR laws are very robust.

We end this weekend’s Substack with a long read about how a slave girl and a barber encountered an Ancient Bablyonian King along the Euphrates River some 3,700 years ago.

The late 18th century BCE, when the Gimil-Ninkarrak tablets were produced, was more than 2,300 years before the birth of Muhammad, 1,200 years, even, before the beginning of the Roman Republic. But urban culture was already about 1,800 years old in the Middle East. And because people, rightly, always consider their own era modern, Gimil-Ninkarrak would not have thought of his culture as primitive or ancient.

Gimil-Ninkarrak lived in what was then one of the most urban and densely populated areas in the world: the region that came to be known as Mesopotamia (modern Iraq and Syria), where cities and kingdoms lay in the valley of the great Euphrates and Tigris rivers. The major cities were grand; with populations in the tens of thousands, they boasted sprawling palaces, towering city walls, and temples on high platforms. The sizable city of Terqa was home to the great god of the region, a grain deity named Dagan.

During Gimil-Ninkarrak’s lifetime, the major power in Mesopotamia was a kingdom called Babylon. You may be familiar with Babylon from the Bible, when Nebuchadnezzar II was king, but that story would not unfold for more than 1,100 years. Gimil-Ninkarrak’s era was what we call the Old Babylonian period, when the city of Babylon was just beginning its almost 1,500-year domination of what is now Iraq. The Old Babylonian empire had been forged by a king named Hammurabi, and Gimil-Ninkarrak may have been born around the end of Hammurabi’s reign.

Thank you once again for checking out my Substack. Hit the like button and use the share button to share this across social media. Leave a comment below if the mood strikes you. And don’t forget to subscribe if you haven’t done so already.

Hit the like button above to like this entry and use the share button to share this across social media.

Leave a comment if the mood strikes you to do so (be nice!), and please consider subscribing if you haven't done so already.

The difference between ChatGPT and a parrot, is that a parrot is aware that it is engaged in mimicry.