FbF Book Club: The Final Pagan Generation (Watts, 2015)

Chapters 6 and 7 - Return to "Normalcy", the Christian Counterculture, Ascetics with Street Cred, Athanasius' Life of Antony, Elite Overproduction

Previous Entry - Chapter 5: Julian the Apostate, Make Paganism Great Again, Compromise, and the "Deep Empire"

Before we dive back into the book:

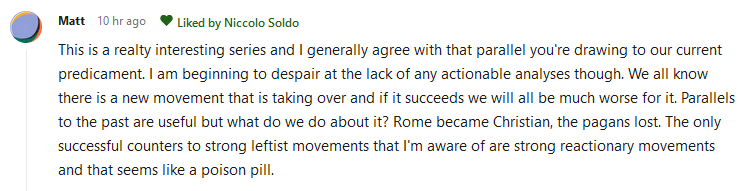

Matt left this comment below yesterday’s entry. This is a valid criticism which I intend to address at the end of this series. Every parallel that has been drawn as I go through this book leaves me wondering: “How can this be countered?” There is little point in drawing these parallels without applying the lessons that we learn from them. The problem that we are left with is coming up with realistic and actionable solutions. I will ask you to think about what can be done to address this as we head towards the conclusion of Watt’s book.

A semblance of normality seemed to have blanketed the Roman Empire despite the deaths in quick succession of its last three Emperors. It was this very last one, Jovian, who plotted a middle course between the pro-Christian policies of Constantius and the pro-pagan ones of Julian, his immediate predecessor. This middle path perfectly fit in with the fact that he was a consensus candidate for Emperor. The excesses of the previous two cancelled each other out, allowing Rome to return to the business of empire. Something was brewing beneath this semblance, threatening the delicate balance borne out of this consensus.

I’ve chosen to condense the sixth and seventh chapters of this book for the simple reason that Chapter 6 does not dwell too much on the themes that interest us. Jovian’s premature death resulted in the naming of Pannonian military officer Valentinian as Emperor, with him naming his brother Valens as co-Emperor (they are pictured above on the gold coin). Valentinian would rule in the West, and Valens in the East.

The brothers’ reign was an interregnum of sorts, concerned more with administrative reform and almost wholly uninterested with religious matters (despite the brothers being Christians). They inherited depleted imperial coffers due to Julian’s fiscal mismanagement (which Jovian did not have time to address due to the shortness of his rule) and set about correcting the situation while weighed down by financial obligations to those in the service of the Empire, plus others who had gained its favour. These fiscal reforms were painful, and resulted in a rebellion led by Procopius that was quickly put down by the brothers. To prevent another rebellion from breaking out, Valentinian and Valens purged the Roman administration of untrustworthy and ineffective officials. They then filled these roles with their own loyal Pannonians alongside others chosen from reliable provincial elites.

Valentinian, who was no religious zealot and privileged unproblematic administration over unnecessary religious conflict, would have been inclined to listen.99 In fact, later in his reign, Valentinian came to be seen as a benefactor of traditional cults in Greece. Both Valentinian and Valens were given honors on the Sacred Way linking Athens and Eleusis, and each had statues erected to commemorate their benefactions to Delphi.

To quote Rodney King: “Can’t we all just get along?”