FbF Book Club: The Final Pagan Generation (Watts, 2015)

Chapter 2 - Constantine the Great, De-Paganization, Incrementalism, Continuity, and Elite Training

(Please do consider sharing this entry on social media, especially Twitter, where I am currently suspended. Thank you.)

Previous Entry - Introduction and Chapter 1

Watts’ methodology is both chronological and parallel-streamed in that he walks us through 4th century Rome by not only taking a look at the big picture, but also through the vehicle of the everyday lives of Romans, particularly its elites, with a specific focus on the generation born beginning in AD 310, which he calls “The Final Pagan Generation”, and which we saw in the previous entry of this book club. There are four men of that age that he uses as primary sources to help us better understand the transition from Paganism to Christianity, Libanius, Themistius, Ausonius, and Praetextatus.

All four of these men were of the wealthy elites. They grew up to be key decision makers in their locales, and the first three left quite a lot of written material that still exists to this day (Praetextatus is the exception, but so much material has survived to the present that is about him or involves him that Watts has included him with the first three listed). Watts uses them to not only show us what was going on at various times throughout their lives, but also to illustrate how they reacted (or didn’t react) to the changes happening around them as they passed from one generation to the next, climbing up the political and social ladders in front of them. The second chapter of this history concerns itself with two things: Constantine the Great’s adoption of Christianity (and all that immediately followed from it) and the schooling of the elites of the Last Pagan Generation.

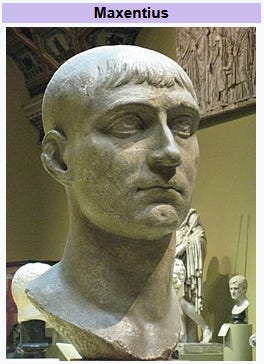

We all know the story of how Constantine saw a vision of a “solar halo” which inspired him to invoke Christ and have his men paint crosses on their shields as they invaded Roman Italy to remove Maxentius from power in AD 312. This victory catapulted Constantine into the position of co-Emperor with Licinius, whom he later defeated, arrested, and executed (AD 324), becoming sole Emperor of Rome, and the first Christian to rule over its entirety. This culminated in Constantine convening the First Council of Nicaea a year later, in which more tenets of the Faith were hammered out by the attending Bishops.

That’s the short version of the history. The actual version is of course a bit more nuanced and complex, and Watts handles this complexity in a rather deft manner. The eventual dominance of Christianity over the Roman Empire is seen by many as an inevitable outcome due to its steady growth, the persistence of its faithful, and the adoption of that faith by Constantine. But was it really inevitable? This is one of the questions that Watts asks in this chapter. I am fond of stating that the present condition in the USA (and the West, by extension), is an inevitable and logical outcome of the primacy of the individual in the philosophy underpinning Anglo-America, one which that individual is liberated from all that binds him, even biology. My contention is that this is an unstoppable train that must reach its destination, running over whatever is in its path, reaching the end to safety or a horrible crash. Am I correct? Only time will tell.